It’s all well and good to discuss next-generation consoles in terms of their computational prowess, their graphical capabilities, and the kinds of games that will be available at launch. But what IGN games editor-in-chief Tina Amini sat down to discuss with screenwriter (Rogue One: A Star Wars Story), game writer (The Walking Dead), and streamer (including Animal Talking, an Animal Crossing talk show) Gary Whitta was about the kinds of stories that the upcoming consoles will enable narrative designers and writers to tell.

During the first day of the GamesBeat Summit 2020, Amini interviewed Whitta about his perspective on next-gen gaming and the effect that better technology and new tools will have on games and their stories. When asked about his thoughts on what the PlayStation 5 and Xbox Series X might bring to video games as a storytelling medium, Whitta noted that both platforms are trying something new.

“What Microsoft and Sony are trying to do more with this new generation than in previous ones,” Whitta noted, “is asking the question ‘Okay, beyond [graphics and teraflops], what are the technological tools that will enable us to explore new and more interesting concepts in game design?’”

The obsession with graphics is ongoing, but Amini reminded us that what fans are also interested in is the content that’s going to be available on next-generation consoles, not just in what the devices are capable of. Part of that capability is in furthering video games as a storytelling medium, not just as an extension of film or theater.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Whitta described the evolution of storytelling in cinema as graduating from flat, one-camera shots to multiple camera angles and sophisticated editing techniques, moving away from what the stage does and adopting a wholly owned storytelling medium for cinema and cinema alone.

Gaming has yet to do that.

“I think that we’re still very much in the silent movie era of video game storytelling,” Whitta said. “What I mean by that is that we’re still figuring out how to use the tools that are unique to our medium. Every new storytelling medium that has ever come along in history … the first thing it does, before it matures, is copy what came before.”

Beyond Bandersnatch

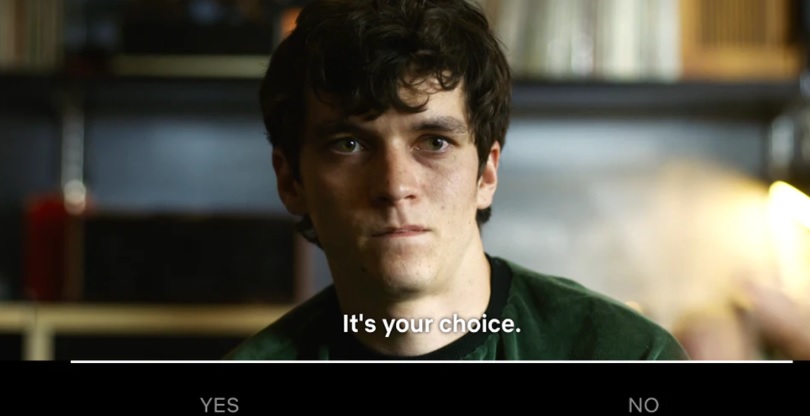

Games are singular in their interactivity. As a medium, gaming can tell stories that other forms can’t. Black Mirror’s Bandersnatch may come close, but it isn’t the same thing. There are still limitations present in a medium where the limitations shouldn’t be nearly as apparent, since you don’t have to “deal with physics or crunching numbers,” Amini remarked.

“Bandersnatch needs to work on SmartTVs and Roku Sticks,” Whitta said. “[These devices] don’t have the technological muscle in order to back it up. It’s experimental. It’s cool. It’s promising. Maybe 10 years from now, we’re going to see full-on, big budget Hollywood productions with triple-A actors where the audience is invited to participate and engage.”

Above: Netflix’s Black Mirror: Bandersnatch let you choose the outcomes.

Even if an experience like Black Mirror’s Bandersnatch works, Whitta hopes that studios will lean into that difference and celebrate it, instead of focusing on being “cinematic.”

“Why not be a video game?” Whitta pointed out. “Why not lean into the unique tools and experiences that video games can do that even movies and television cannot? Number one [on the] wishlist, beyond the graphics and the framerate and the quality of life improvements, is that the technology is going to allow us to explore storytelling design in a way beyond what we currently think is possible.”

“We’re still trying to figure out the technique and the craft. We know a lot of the nuts and bolts of video game storytelling, but there’s also vast unexplored areas that the interactive stuff makes possible that we haven’t even begun to touch upon yet. Some of that is that we don’t have the technology available, the tools available, to really go to town on those things. My hope is that with [Xbox] Series X and PlayStation 5 and as PCs become more and more powerful, game designers will be able to explore these unexplored areas.”

The illusion of choice

There’s some fatigue around the “choose your own adventure” style of narrative games that have cropped up over the course of the last generation of gaming, especially for Whitta. Despite his own love of “The Walking Dead, Mass Effect, Detroit: Become Human, and games that offer the opportunity to branch the story based on the choices you make,” the choices are too transparent.

Instead, Whitta wants to see that kind of narrative branching become “more opaque, in a way that more closely mirrors real life.” After all, in real life, it’s not often apparent which choices are going to have major (or even minor) consequences attached to them. Life is a result of “thousands of little choices that you make every day,” and the effects of the most consequential choices are often unseen and unknown in the moment.

Detroit: Become Human’s approach is a fascinating twist on transparency, according to Whitta. It tells the player everything that they did throughout the game, everything that everyone else did, and then everything that they could have done. This could help circumvent a problem that a lot of narrative-driven games struggle with: How do we entice players to come back and play this story again if they think that their choices (and those of their friends) were the only ones? What if there was much more to do, but you just didn’t know it?

Where real life and fiction split apart, as we all know, is that real life is often both unfair and completely nonsensical. Video games, on the other hand, need to make sense and provide a sense of fairness, telegraphed through both the game’s mechanics and its narrative. As Whitta pointed out, an amoral ending for a player that had played a deeply moral character, for example, would leave a player feeling disconnected from the narrative, as though none of their choices meant anything after all. Doing the unexpected is important, but only if that moment (or ending) can be rationalized in a player’s mind.

“‘Oh, I didn’t expect that, but I understand why it happened,’” Whitta explained.

Amini added: “Some of the most entertaining, interesting moments in a big, open-world game is when you stumble on an NPC that you didn’t expect a reaction from. The immediacy and realness creates these really engaging moments that, in themselves, feel like an unexplored narrative.”

Keeping that narrative going is vital to engagement, too. A person makes a decision every single second of their lives, so if you’re sitting down and playing a narrative-driven game, that game needs to be asking you to do something at least every 25 seconds, per what Whitta learned from working with Sean Vanaman. Vanaman was lead writer and co-project lead on Telltale’s The Walking Dead (first season), founded Campo Santo, and made Firewatch. Valve later purchased that studio in April 2018.

“My dream is to increase both the granularity and the opacity of the choices and the consequences you’re making moment-to-moment in every game,” Whitta said, “so that you never have a moment to relax. I want to get to a place where you’re leaning forward in every moment because you never know when you’re going to be asked to make a consequential choice.”