When President Donald Trump met with video game leaders about violence in games in March 2018, the industry worried he would use games as a scapegoat for mass shootings. Instead, Trump showed his cards to Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Florida). After the game industry made its case — that the U.S. is the only country where mass shootings happen so frequently while games are global — Trump said to Rubio, “We got a problem, Marco, and it’s not these guys.”

Fast-forward to last week, in the wake of the shootings in El Paso and Dayton that left more than 80 people dead, Trump said video games have created a culture of “the glorification of violence in our society,” and that has to stop. The game industry repeated its talking points about how research showed no connection between violence in games and in the world.

Too much silence

Above: President Donald Trump addresses gun violence in a speech.

But Trump didn’t acknowledge that this time around. Rather than challenge the gun ownership problem in his core base, he blamed games. And he wasn’t the only one who flip-flopped, blaming games in an effort to distract people from the problem of guns. Walmart followed up by taking down video game displays and removing violent games from some of its stores. That followed another major setback for video games in May when the World Health Organization official recognized game addiction as a medical condition.

The game community that has grown up with games can see the B.S. in the blame game. I would agree that the video game lobby should fight back, giving the National Rifle Association a dose of its own medicine by attacking the Republican stance on guns, as suggested in an editorial by GamesBeat op-ed editor Rowan Kaiser.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

“What I view is an abject failure of the game industry to engage the public,” said Kate Edwards, an outspoken advocate for game developers, in an interview with GamesBeat.

Speaking in agreement with Kaiser’s article, Edwards (who is the new executive director of the Global Game Jam), said, “The NRA and other organizations lobby fiercely against video games, and we tend to remain pretty silent. We say we don’t agree. The research doesn’t show games cause violence. OK, great. But what about the times between the incidents? What about engaging the public in a way that actually gets them thinking about what our medium really is.”

It may seem cowardly for the game lobby group, the Entertainment Software Association, to back down from this fight. But it clearly has a lot to lose by publicly attacking Republicans or the right-wingers. Fans on the right might be offended and opt to not buy games, and the Republicans might never be friendly toward the industry again for taking such a stance.

“I can understand the commercial or the political reasons for why they don’t want to go that way,” said Edwards. “But that basically tells me that there’s a huge courage gap in our industry. And you know, honestly, we already saw this during Gamergate. Our industry basically cowered and became silent in the face of what they knew was wrong. As I keep telling people when I give advocacy lectures, evil triumphs when good people do nothing.”

The gray area

Above: Mortal Kombat II — the original violent boogeyman.

I play a lot of games, and I’ve long been in the camp that believes that games are a form of art. They have reached the highest artistic levels in reshaping narrative with interactivity. Games are protected speech, under the First Amendment, and we’ve litigated that already. They’re not harmful, based on research. Other issues, such the availability of guns, are the main problem. Games are so much more than a single violent scene. They are expansive, diverse, and combine multiple art forms in a single creation. They’re literary creations.

But that doesn’t mean game violence and addiction are black-and-white issues for me. I’ve gone on the record saying that the latest Call of Duty: Modern Warfare game disturbs me with its realistic violence, because it blurs between soldiers and civilians, and because it has other troubling elements, such as child warriors.

It’s gray world, as the Call of Duty game points out, and the politics of games are gray too. Sadly, I can’t join the united front against the enemies of games because reality is so awkward. It reminds me of the days when video games were first put under the spotlight of Congress in the 1980s, when Mortal Kombat sparked congressional hearings on violence.

History repeats itself

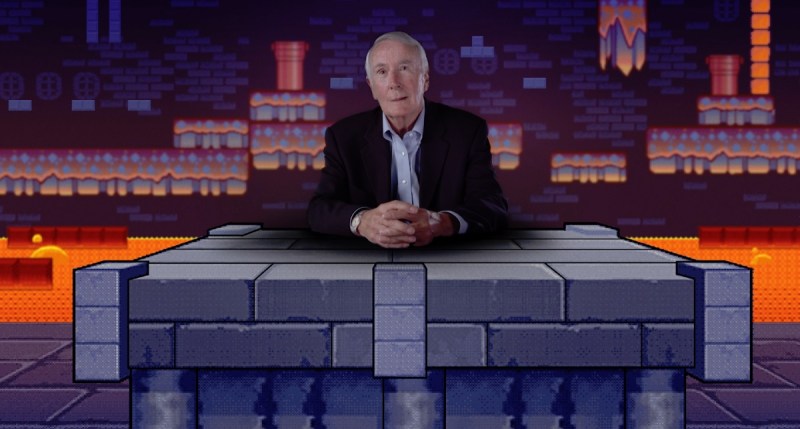

Above: Howard Lincoln is a former chairperson of Nintendo of America.

Back then, Nintendo chairperson Howard Lincoln criticized Tom Kalinske of Sega for bringing the heat of the government down on games because of the irresponsible publishing of the red blood version of Mortal Kombat on the Sega Genesis. Nintendo published a game that was more family friendly, with gray blood, and Sega outsold Nintendo by 5-to-1.

But to outrun government censorship, the game industry buried its disagreements and came up with its own self-governing ratings system. The industry matured and became far more diverse as well, with titles appealing to just about every demographic.

“Now, what I’ve learned is that video games are an integral part of American culture,” said Spencer Halpin, who years ago made a film called Moral Kombat (and I was in it). “Three-quarters of our country has at least one gamer in their house — I have two. And it was an immature industry that has grown up a lot.”

Today, that ratings system born in the age of Mortal Kombat will be put to the test with Modern Warfare. If it gets an Adults-Only rating for violence, that’s the kiss of death. Right now, the Call of Duty game appears to be rated Mature. But we’ll see if that rating is appropriate when it debuts October 25.

Already, I’ve seen other game developers say that publishing this game at a time of heightened national sensitivities around violence is irresponsible. That suggests to me that the united front is not strong. Even if games don’t cause mass shootings, the violence in games can be disturbing.

The question is more about whether games are created as a form of art or as a commercial product. The intentions matter. If developers are creating art, they are fully protected by the 2011 U.S. Supreme Court decision where the court overturned a California law seeking to limit sales of violent video games. That matter was settled, and we don’t have a need to relitigate it.

But both the public and other game developers often wonder whether game companies are too commercial, as if they want to exploit consumers rather than serve them. In 2007, Strauss Zelnick, the CEO of Grand Theft Auto publisher Take-Two Interactive, said that he was responsible for the line between entertainment and exploitation when it came to deciding what to publish. Recently, he almost pointed a finger at guns instead of games, but held back.

Self-restraint is important for artists. Because they have the freedom to march alongside Nazis marching in Skokie, Illinois, in celebration of free speech does not mean they should. Because we can burn the American flag does not mean we should. And so on. As Spider-Man says, “With great power comes great responsibility.”

I have often tried to inspire developers to make great art that makes use of their creative talents. I tell people about the fitting moral of the Kurt Vonnegut novel, Mother Night. It’s about a double agent in World War II who did his cover role as a Nazi propagandist too well. The moral was, “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.” My extension to that was, “You are what you play.”

Above: A Star Wars demo shows off real-time ray tracing.

I think you should be careful about what you play. But a lot of people don’t feel that way and they think of games as escapist fantasy. Most of us don’t have a single kind of reaction to playing games, and that’s what is wonderful about both games and human beings.

Yet some companies can ruin the party. If businesses Facebook gets caught discussing how to make in-app purchases easier for children to make without parental permission (as they have been), then that’s a blow for the trust that consumers have in the industry.

If companies like Sega see an opportunity to beat Nintendo in a Darwinian competition by exploiting the love for violence in a video game, then that rightfully causes some parents to become indignant. If game companies take lessons from gambling companies in creating loot boxes that are more addictive for gamers to purchase, then the industry rightfully deserves the scrutiny of the Federal Trade Commission.

This scenario could be dangerous. If game companies create addictive loot boxes with highly tuned analytics in the same way the cigarette industry tried to lure young smokers or that casinos have tried to recruit new gamblers, then the industry risks running afoul of government action that could bring far more scrutiny than violent content could.

Above: Kim Libreri, CTO of Epic Games, shows off A Boy and His Kite.

Mass shootings will come and go, and they will be reduced if we get more control of the guns in American society. But the worries about addiction and exploitation are with us for good. I think the game industry should speak more honestly about addressing these issues.

Over time, the violence issue will only get more pronounced with better realism. The consoles coming next year and the ever-improving PC will put greater power in the hands of the industry’s most brilliant programmers. Do you remember when rendering water was very difficult for game developers? It always looked fake. But not anymore. The same goes for rendering blood.

Once in a while, we can get bipartisan support. Everybody tends to agree that killing Nazis in a game like Wolfenstein: Youngblood is OK. The German government is allowing swastikas to be used in video games for the first time. But wary of exploitation, it does not allow the use of swastikas in advertising or retail material. That is probably a good way to walk the line between freedom and responsibility.

Above: Epic Games’ Siren demo is an example of digital humans — and how real they’re becoming.

This near-perfection in graphics will make it much more disturbing when it comes to the depiction of violence against human beings. And when those game characters — also known more broadly as virtual beings — become infused with artificial intelligence, they will feel even more real. Would it still be OK to shoot such near-sentient characters who look almost exactly like living beings? Because we can render artificial human beings in a way that makes them easy to exploit — like creating sex slaves — we should not just go do it?

And as violence gets worse and realism becomes more immersive, the addiction could also get worse.

Presenting a united front against the government censors, the political demagogues, and angry parents is fine — particularly if you only have 140 characters to make your case. But the industry should not ignore the disturbing issues that come with the creation of games in an open, toxic society and a capitalistic environment that rewards the lowest common denominator. We should not be silent about discussing the gray areas of realistic violence and addiction. I haven’t even mentioned toxic gamer culture yet, but, yes, we should discuss that too.

I’ll be moderating a discussion on this topic in a panel at Devcom on Sunday at 5 p.m. in Cologne, Germany. I hope goes the dialogue goes well, for the whole industry’s sake.