This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Editor's note: I've voiced my dislike for quick-time events before, and Suriel's examination hasn't changed my opinion. His best example of God of War ignores the fact that the QTE inputs are disconnected from the actual combat gameplay, which I feel is the defining characteristic that places the mechanic solidly in the lazy design category. -Rob

You used to know what parts of a game you could play and what parts you couldn’t.

When Toad informed Mario that his princess was, in fact, in another castle (sorry, I had to do it), Mario appropriately kept his mouth shut and didn’t move. Early Ninja Gaiden games had cut-scenes that were entirely about exposition and crafting a better story — even if they never came off as well as they should've.

Even today, most games have a divide between interaction and watching as the story cements itself. Recently, though, developers have left that behind in favor of involving players in cinematic sequences in what are now dubbed quick-time events (QTE).

For the uninformed, a QTE is (as defined by Wikipedia):

A method of gameplay used in video games. It allows for limited control of the

game character during cut-scenes or cinematic sequences, and

generally involves the player following onscreen prompts to press buttons.

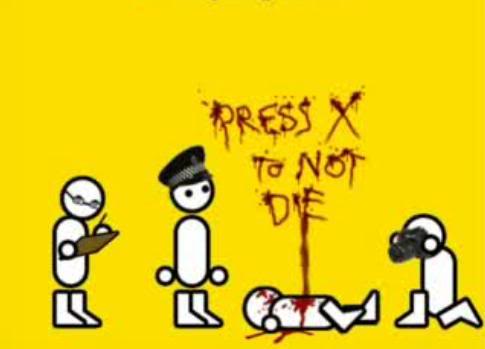

I must have "played" this cut-scene fifteen times. Seriously.

Of course, the intent is to engage players in order to (seemingly) prevent them from getting bored with what’s going on. Pressing buttons or performing simple actions allows you to continue forward, while failing to do so means being handed a penalty — usually death.

With all the wide uses found for QTEs today, is this a valid way to have players interact with their games, or is the mechanic a crutch for developers to lean on when they can’t decide whether to make a part interactive or not?

With entire games based upon this premise, you would think that QTEs would be a perfectly reasonable mechanic. Judging a player’s reflexes is a way to test their "skill" in action games, along with their timing and whatnot.

But if you’re going to test a player's reflexes or timing, wouldn’t the best place to do so be in the game proper — not in a cut-scene? Because of this, the purpose of the QTE in a cut-scene is not to challenge the player’s skills, but rather to engage him in what’s happening on-screen.

This does not, though, invalidate the mechanic's use. Just because the button pressing and stick twirling is not inherently challenging, it doesn’t mean that it can’t be done well. One of the best examples (and one of the most often cited) is God of War.

But they’re not exactly quick-time events because they don’t take place in a cut-scene. When you initiate a sequence to kill a Cyclops, you have one button to press that will then launch you into the next part, and so on. This essentially makes it an in-game, quick-time event.

Assassin's Creed 2 improved on the first game's biggest omission: the lack of baby-feet moving.

This is one of the QTE's best uses, because Kratos has no way to jump on a Cyclops and then gouge its eye out. It just isn’t possible in normal gameplay. But it would be too easy to just press one button and watch the entire thing unfold. (And yes, I am saying that instances that do just that are not good ways to use quick-time events.)

Recently, though, while playing through the God of War Collection and Dante's Inferno back-to-back, I've become tired of the "do-or-die" approach to QTEs. It's nice to able to perform moves in regular combat that would otherwise not be impossible, but failing and having to try again wrings all of my enjoyment from the experience.

The newest Prince of Persia (the 2008 release — not The Forgotten Sands) also puts the mechanic to work extensively. A pseudo-QTE pops up as you fall off something and plummet to your death; the screen turns white, and you have to retry the jump. Also, the game pretty much tells you when to block every time, so little in the way of difficulty exists — but that's an entry for another day. The point is that these are examples of QTEs' overuse, and they become a nuisance more often than not.

But simply because a few games are overzealous in their execution doesn't mean the concept is useless. Regardless of where you fall in the debate of its quality, Heavy Rain might just be the best use of QTEs yet; instead of punishing failure with death, you're simply lead down another thread, and the result could be a seamless experience that capitalizes on the power of contextual button-presses, instead of using them as a gimmick.

I wrote this post long ago on my personal blog, but I've re-posted it here for your reading pleasure while I continue working on Year One. I've also updated some of my thoughts on the subject.