This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Editor's note: Similar to the "Are games art?" debate, the one over which review scale is best just…won't…die. Fortunately, Suriel intelligently breaks down the options out there and gives us the lowdown on each. What do you, the Bitmob community, feel is the best scale? -Greg

After mulling over the decision for a quite a while, I've decided that I will start adding scores to my reviews*. In an ideal world, I could just transcribe my opinion about a game and know that everyone who reads it will know whether the game in question is right for them.

Unfortunately, we don't live in an ideal world, and scores are, in my opinion, necessary. While many critics loathe having to quantify their thoughts on a game and assert that the review should speak for itself, and as much as I'd like as many people as possible to read my writing, as a critic, you're ultimately serving your reader; it's somewhat pretentious to think that everyone should be forced to sit down and read what you have to say. I'm not writing a long-winded essay about how the game reflects on our culture, I'm answering a simple question: should you buy this game?

I'm not exactly in the position to demand that sort of attention from my readers, either. I'm a relative amateur in the field of video game writing, so I must make concessions to the reader before I can expect them to trust or relate to my point of view. Rather than being a crutch, review scores are a way to hold myself accountable. My text and score should more or less match — with a certain amount of wiggle room for interpretation — and if they don't, then it's because of my failure to properly articulate my thoughts. I need something to keep my writing in check; otherwise, I focus on nitpicks and make a review take on a different tone than I intended it to.

But enough background. The point of this post is to try to decide what scale I should use from now on. The 1-to-10 scale seems fairly reliable, since it can tell you at a glance what the critic thinks of a game, at least in ballpark figures. The problem with this scale is that it is subject to too much interpretation: Is 7 a good or bad score? Since it's above 5 — the average — it's technically an above-average score, but in most school systems, a 70 (7/10) is a D or a C, which is either at or below average.

With that in mind, I decided to take a look at a number of alternatives to this scale. Many of them are already being used elsewhere, while others are mostly theoretical. Still, it's important to know your options before you commit to something, so here are some of the ways I've considered helping consumers decide which games they should or should not buy.

1-to-5

Though this scale is very similar to the 1-to-10 scale, there's one key difference: the lack of granularity. You don't have to worry about whether that 7 is good or bad when it isn't an option. 1 is horrible, 2 is bad, 3 is average, 4 is good, 5 is great/amazing/astounding/positive multisyllabic adjective.

With such a limited range of scores, it's harder for readers to get hung up on whether game X is better than game Y, so it's not the best for comparative shopping, but it also helps mitigate the fanboy forum wars about the difference between a 9.4 and a 9.6. It's best used when deciding on whether you should buy a particular game, which is the usually the situation anyway. If you're choosing between two games with similar scores, it's a personal decision that most reviews aren't going to help you with, and you're likely going to go back and buy the other game at some point.

It's also important to point out the difference between scales that use half-stars and those that don't. Using half-stars essentially turns a scale into a 10-point scale, but let's be honest — most 10-point scales are either 20- or 100-point scales. I personally prefer the scale without half-stars, since it forces the reviewer to decide whether the game is simply good or great. People won't usually say, "This game is good and a half!" but nonetheless, both options are valid.

Letter Grade

Letter GradeDoing away with numbers entirely, the letter grade offers a way to quantify the reviewer's thoughts on a game without having to worry about fractions or percentages. The benefits of assigning a letter rather than a letter are clear: they're much easier to understand than numbers. Since most of us are already aware of what the letters A, B, C, D, and F** stand for, seeing that grade attached to a review makes perfectly clear what a reviewer thinks. We all know that a C is average, a B is good, and so on. You don't have to wander in the 7/7.5 territory of whether something is good or great.

There are, however, some difficulties to overcome. When you add pluses and minuses to the scale, it can get a bit hard to interpret. What's the difference between a B and a B+? Though B+ is clearly a better grade for a game to receive, what's the threshold for purchasing a B game versus a B+? These things make it somewhat difficult for buyers to assess whether a game is for them.

Not only that, but Metacritic has difficulty with sorting that type of thing out. The way it changes letters to numbers is extremely shady, and while many critics loathe Metacritic on principle and would easily dismiss whatever they did to their grade, the fact is many people are going to simply glance at the Metacritic scores, where your C might turn into a 66, and it's likely that you'll disagree with this score. The letter grade is a great way to avoid the numbers game (excuse the pun), but it's something of an outcast in the number-fueled review world.

The system becomes a lot less confusing when you remove the modifiers, and this makes it much easier for Metacritic to turn your B into an 80, but at that point, you're essentially using the five-point scale. At least the modifiers give some wiggle room for the reviewer to argue with aggregator over the interpretation of their grade.

Dollar Amount

Ryan Conway is already experimenting with this system, and the results have been encouraging. Instead of giving you a score to gauge whether you should buy a game, Ryan simply tells you at what price you should buy a game, while also comparing it to the game's current price.

Ryan Conway is already experimenting with this system, and the results have been encouraging. Instead of giving you a score to gauge whether you should buy a game, Ryan simply tells you at what price you should buy a game, while also comparing it to the game's current price.

This system accounts for the variety of pricing available for video games. Ideally, a game's evaluated price and actual price will match, but since that's hardly ever the case, giving you a dollar amount to aim for seems reasonable. It makes a value judgment rather than a qualitative one, so it assumes you're already interested in the game and would simply like to know whether the game you're looking to buy is worth what you're spending. The scale is very consumer-minded, which, being a review telling people whether they should buy a game or not, it should be.

With this scale, the arguments of which game is better die off almost completely. Giving you a dollar amount isn't saying that this is the greatest game ever made or that it redefines our medium, it just says, "You should buy this game at this price," which is what most people want. Though many people will buy most if not all of their games at launch day, plenty of people will wait until the game goes down in price, and this scale tells them when to start hunting for a game.

However, the value argument isn't bullet-proof. Will a game like Heavy Rain be a good value proposition? There's a difference between a game having a good amount of content to keep you busy and it being a great experience. Now, it's possible that a Heavy Rain will be good enough to merit its $60 price tag, but if someone were to look at a review of Fallout 3, for example, and saw that the game had received the same score, and picked up Heavy Rain thinking it would be the same value, it's likely they'll be disappointed by the lack of content. Still, it's a bold new direction in reviews that merits praise.

One Critic, Two Scores

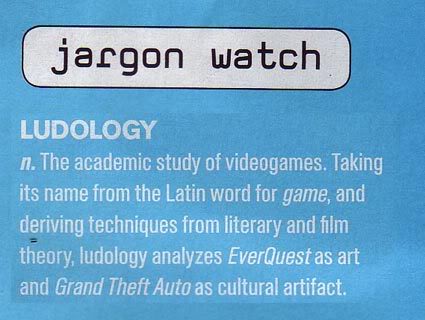

This scale was first kicked around by Jon over at the Taipei Gamer Blog, and it caught my attention via the Penny Arcade news post "On Perspective." The idea is to evaluate the game in two separate but equal ways: in the ways that it uses the video game medium to its advantage, and the ways it carries itself as art. Jon explains further:

The L-Score [L for Ludology***] is the score which is most closely related to the uniqueness of the medium. I have argued before that games are different from art because they aren't simply admired, they are also played. It is the interactive nature of games which ludologists emphasize, and so one can think of the L-Score as a metric for gameplay and game design. Mechanics, systems, and level design are the key components measured by the L-Score.

If the L-Score is a measure of a game's design, then the N-Score [N for Narratology] is a measure of its artistic achievement. The narrative, in this case, is defined rather broadly. It consists of the game's music, writing, visual style, sound design, overall setting, etc. All of these factors influence the player's involvement in the game and are therefore important even if they don't have much of a direct impact on the actual gameplay.

Essentially, Jon attempts to appease both the people who value games because they're not like other forms of art and the people who value their artistic merits above most else. This scale acknowledges that although games have the capacity to be high art, the things that makes games what they are are equally valuable. Something like a schmup may not receive a very high N-Score, but it would receive a high L-Score — assuming it's good, of course. The advantages of a scale that can give Gears of War both a "perfect" score and an extremely low score at the same time cannot be overlooked.

Essentially, Jon attempts to appease both the people who value games because they're not like other forms of art and the people who value their artistic merits above most else. This scale acknowledges that although games have the capacity to be high art, the things that makes games what they are are equally valuable. Something like a schmup may not receive a very high N-Score, but it would receive a high L-Score — assuming it's good, of course. The advantages of a scale that can give Gears of War both a "perfect" score and an extremely low score at the same time cannot be overlooked.

Though I'm sure it's not the scale's express purpose, it does a very good job of sticking it to Metacritic. If a game gets a 10/0 on this scale, the reasonable thing for the aggregator to do would be to take the average of both scores and give the game a 5, but that would be missing the point entirely. It could also take the highest of the two scores, but that would also be missing the point. Simply put, it's impossible to turn two numbers that mean completely different things into one thing that represents both.

But while it's very good at evaluating something by two distinct standards, it's very confusing from a consumer perspective. Assuming that a person is simply looking at all the reviews for a particular games and stumbles upon a review set up this way, it will take them a while to understand what the scores are trying to say. It's a great tool to encourage in-depth discussion of games, but not necessarily to answer the ultimate question a review should be answering.

Percentage Chance

Percentage scales are often interchangeable with the 100-point scale, but I think there's potential to do something different here. Rather than thinking of a score in terms of "How good is this game?" we can instead change our thinking to "What are the chances someone will like this game?"

Percentage scales are often interchangeable with the 100-point scale, but I think there's potential to do something different here. Rather than thinking of a score in terms of "How good is this game?" we can instead change our thinking to "What are the chances someone will like this game?"

This mindset changes the way one should approach a score. Though the best game ever made might merit a 10 out of 10, will everyone who reads it like it as much as you did? There are many niche titles in gaming, and though many of them are good, one can easily see why someone would or wouldn't like a title entirely dedicated to flying around and being a flower.

I like this system because it accounts for both taste and quality, but it's not without faults. By this metric, it's impossible to achieve a 0% or 100%, since no one game will appeal to everyone's taste, and not everyone will hate a game. Besides, regardless or your intent, people and aggregators alike will just see your score as a number anyway. Additionally, get too bogged down with demographics and tastes, and too many games are going to end up near 50% if you're using the scale correctly. While that assertion may certainly ring true, it won't help anyone make a decision. This scale is more the field of marketing and statistics.

Yes or No

Speaking of statistics, my stats teacher once told me something that stuck with me: No matter what the chances of a given event are of happening, for any individual trial, the probability of any outcome will always be either 1 or 0; either that outcome will occur or it won't. And for someone who's on trial for murder, that's all that matters.

Speaking of statistics, my stats teacher once told me something that stuck with me: No matter what the chances of a given event are of happening, for any individual trial, the probability of any outcome will always be either 1 or 0; either that outcome will occur or it won't. And for someone who's on trial for murder, that's all that matters.

With that in mind, the Yes or No system (it's not a scale, really) comes into play. You're either going to buy a game or you're not, so why not just get rid of all this 3/5, B+, $40 business and just tell a consumer if they want to buy a game or not. This system is best at answering our question because it does nothing else. You could always buy a game later — at a lower price — but the decision has already made, just postponed.

Though it seems effective from a consumer standpoint, it lacks a certain amount of granularity. A decision of yes or no will always be up to the consumer, regardless of what the reviewer thinks; a reviewer will never have the exact same taste as the reader, so the authoritativeness of this system rings false. Besides, use this system long enough and you're going to start attaching caveats to every review — "yes if you're a fan of the genre, no if you're not" — that it will make the concept of deciding more and more tricky and the system more and more pointless.

Buy/Rent/Don't Buy

A slight variation on the Yes or No system, but no less worth going over. If Yes or No attempts to answer the question of whether you should buy the game, Buy/Rent/Don't Buy answers the question of whether you should play a game. It's this important difference that adds the "Rent" option. This system primarily takes into account length; if a game is only about four hours long but really good, then a perspective buyer should probably rent the game in order to get the experience of the game without paying for something that they might end up regretting.

Though this system is more versatile than Yes or No, it still suffers from some of the same flaws. You'll often have to attach caveats to such reviews, which will make it difficult in deciding whether one should play the game or not. Still, both of these systems are great for at-a-glance evaluations and could possibly save a Christmas or two.

Conclusion

So, which system shall I use to evaluate games from now on? Well, I'm gonna sleep on it for a bit****. Bu, in writing this I've contemplated my options much more clearly than had I just paced about my room for an hour. I've also hopefully given some of you something to talk about, and maybe I'll bounce some ideas off of some of you. Who knows, maybe someone important will pick this up and start using some of these ideas. And hopefully give me a job*****.

And if there are any sort of other review systems you'd like to mention, please feel free to do so.

*For now, previous reviews won't be scored, since adding a score would reflect my thoughts on a game now rather than when I wrote the review. Whether or not one should go back and change or add scores is another story. If you absolutely must see scores attached to my previous reviews, you can check my Giant Bomb or 1UP pages.

**I've never understood why letter-grade scales skip the letter E; perhaps to drive home the point that "F" stands for failing?

***You can find an article further explaining Ludology here.

****By which I mean I'm going to take a short break from writing reviews because I'm not made of money, kids.

*****I can dream, can't I?