Rob Pardo developed his relentless focus on excellent game design when he was at Blizzard Entertainment, making games, such as StarCraft, Warcraft III, and World of Warcraft. He learned to experiment and playtest and to do that over and over again until the game felt right. He also learned to let go of games that didn’t meet the highest quality standards and move on to the next project.

He took those sentiments with him when he left Blizzard in 2014, after 17 years at the big game publisher. He was an adviser at Unity for a while and then moved on last year to start Bonfire Studios, which raised $25 million from Andreessen Horowitz and Riot Games. Pardo is now working on a secret project, but he still believes that excellence is something that you try to do every day. He has recruited other like-minded professionals, from Min Kim, former CEO of Nexon America, to former game TV broadcaster Morgan Webb.

Pardo is going to give a talk at The View conference, an event that takes place in Turin, Italy, on October 23 to October 27. I did an interview with him, and he gave me a preview of his talk, dubbed “Excellence Is a Journey, not the Destination.” In our conversation, I tried to extract some stories that help define excellence and quality from his perspective.

He brought up an example of working with Blizzard cofounder Allen Adham on testing a unit in StarCraft. They obsessed over the details and then changed it based on what they found. That iterative process of playing and testing is a critical part of game design, Pardo said. He had some painful times when the work didn’t pay off like when Blizzard canceled Titan, a massively multiplayer online game that Pardo was working on.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Above: Rob Pardo, CEO of Bonfire Studios.

GamesBeat: What is your talk about?

Rob Pardo: I called it “Excellence Is a Journey.” You don’t get these opportunities very much in your career. I had a very long career at Blizzard. I thought that before I get too deep into Bonfire, it’s a good opportunity to reflect back — for myself more than anything and extract all the lessons I learned from the time I was there and try to turn those into things I’ve learned, things that I think led to the success Blizzard had, and that I had as a part of Blizzard. Hopefully, make that something interesting or useful for other people trying to go down the same path.

GamesBeat: Had you ever talked about this before?

Pardo: Not in a retrospective way, which is what I thought would be fun for me and for everyone else. I’ve usually done much more focused talks. I’ve done a couple GDC talks. I’ve done a talk on Blizzard game design values. A lot of my talks are obviously much more design focused. I felt like this crowd, if it does have more of a mix, with people coming from other industries — I wanted to do something more high level. Not just specific to games but hopefully for any creative entertainment endeavors.

GamesBeat: Do you identify with something like the Blizzard way of making games? Do you consider that to be the same as your own view of making games?

Pardo: It’s going to be very hard for me to ever somehow be different from that. I feel like I grew up within Blizzard. So much of my way of thinking about things was forged there with the people that were there. I still continue to believe in a lot of the same tenets as Blizzard, the way they produce games. I don’t know how to separate myself. I’m sure over time, maybe 10 [to] 15 years in the future, I’ll forge some different learnings and lessons at Bonfire, and it’ll be a mix of the two.

GamesBeat: What’s a good way to summarize that? What would you mean by excellence as a journey?

Pardo: Oftentimes, you’re always thinking, “I want to have this great product.” But what I’ve found is that you need to really be focused on the here and now, the people you’re working with, and doing things in the right way. Working with great people and having similar motivations. If you do that well, you’ll end up at a great destination.

What I’ve tried to do is think back through the different projects I’ve been a part of. What are the learnings from each one, some of the high-level learnings? Trying to put that together into my journey of learning how to get better at making games.

Above: Bonfire Studios is based in Irvine, California.

GamesBeat: What are some of those that you think built on your previous games? With, say, World of Warcraft, was there something interesting about that, above and beyond what you’d done before?

Pardo: When you start looking at Blizzard or stuff I was involved in at Blizzard, there are a lot of things that come through. Details matter. Nowadays, when you talk about the Blizzard polish, a lot of that comes from being extremely detail oriented throughout. Being really focused on gameplay, caring about the worlds you create, and making them have emotional resonance for the community. Being very player focused.

These are all things I know I’ve talked about or Blizzard’s talked about for years. But just trying to pull out some more specific anecdotes that make those things more real on a day-to-day basis, rather than talking at a high level about things like. “Don’t ship before it’s ready” is another Blizzard tenet, but what does that really mean? How do you decide when it is time to ship? Those are the types of things I’m trying to get into and trying to tell stories from the development of the different games I was a part of.

GamesBeat: How early did you get there at Blizzard?

Pardo: I joined during the original StarCraft development.

GamesBeat: I don’t know if you ever heard this story — it sounds like you weren’t there for this — but on the first game they did for Brian Fargo, Brian wrote them a long note. “Here’s all the things I’ve noticed about the game. These things are good. These things are bad.” [Blizzard cofounder] Allen Adham looked at the note and said, “We have to make these changes. We can’t ship the game the way it is now.” I guess that would have been the first time that they made that kind of decision.

Pardo: It probably was. That’s when they started, working with Brian on those early Interplay games.

GamesBeat: It was basically a finished game as far as they were concerned up until then. I wonder whether that kind of discussion was easy to have or harder to have. Allen has a big personality around standing by that because it served them so well in the beginning.

Pardo: It’s also just continuing to be that detail oriented. My anecdote from the first time I was working with Allen on StarCraft is that I was really focused on giving lots of qualitative feedback and trying to get the game balanced to be as perfect as possible. But Allen was always testing the nuances of the different unit interactions. He would call me up and have me jump into games with him all the time.

We’d do things like, “Let’s take a science vessel and put a defensive matrix on a unit. Now, we’ll put other buffs on the unit and see whether [or] not the matrix acts how you’d intend it to.” At first, that sounds like game testing, but it’s actually game design. You want to make sure you test all the interactions. Maybe they perform correctly in code, but maybe that’s not how you want the interaction to perform once you walk through it. When you’re on the phone with the CEO of the company doing that sort of work, you realize how important it is to the studio.

GamesBeat: There are all kinds of negative things you could think about that, to that style of management. You could say, “Hey, this is second-guessing my design. Why does anybody want to change it?”

Pardo: I don’t know. I guess I never saw it that way. I see it as — you want to make sure that the gameplay is not only how you intend but it’s intuitive to the end user. It’s as bulletproof as you can make it. We didn’t really know it then, but Blizzard games end up lasting for many years past the point of release. It’s because of that maniacal attention to detail. We were always thinking of things that even the players weren’t thinking of at first.

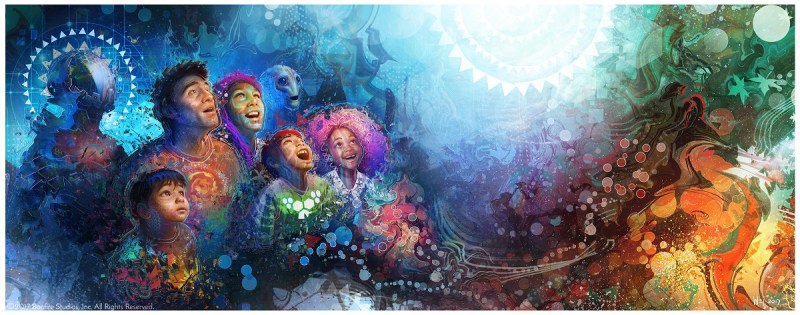

Above: Art from Bonfire Studios.

GamesBeat: As far as that kind of actual player feedback, coming from outside the company, how does that figure into your philosophy?

Pardo: It even starts inside the company, though. The thing about a lot of game companies, although certainly, Blizzard is one of them, is that inside of Blizzard is already your core audience. People that work at Blizzard, they love playing the games Blizzard produces. Right there internally, you already have such a great beginning for how to test the game and learn what’s going to be great for players.

What Blizzard does is expand that concentric ring of exposure to the player base as the game gets further along in development. At first, it’s all internally focused, but Blizzard is such a big company that they can now expand that to other teams that maybe haven’t seen the game before, so it’s still a fresh perspective, but it’s from developers and Blizzard players. And then, you keep on expanding that circle. You start having people from outside the company, friends and family, start playing the game. You do some sort of closed alpha test and then a closed beta test.

That whole process is one of the things that allows Blizzard to make games that are great, that last for many years because it is so player focused. It has this gradual exposure to more and more players as you continue to iterate on the game.

GamesBeat: Did you notice a lot of variations on the philosophy among different people at Blizzard? Would your outlook have been somewhat different from, say, [Blizzard cofounder and president] Mike Morhaime’s?

Pardo: Not at a high level? At a strategic level, I think everyone was pretty aligned on what’s important to the game and what has to happen to make a great Blizzard game. Tactically, everyone has different styles and different leadership philosophies, but at the really high level, the product strategy level, there was always a lot of alignment.

Above: Rob Pardo was a D&D dungeon master for his friends.

GamesBeat: Does it mean that you have to get into the details, even as leader? You have to try to understand the whole game, not just delegate.

Pardo: It depends a bit nowadays because the games are just so much larger in scope, so much more complicated. When we were making the original StarCraft, the entire development team was around 25 people. It’s a much more manageable thing, where you can get as deep into the details as I was talking about. Now, the Blizzard teams are, in some cases, hundreds of people. It’s a lot harder to be microing on every single unit interaction. I don’t think that’s possible anymore.

GamesBeat: If you have to let go of that, what’s the advice you would have for people who want to pay attention but also do their job at the right level?

Pardo: I don’t think there’s a formula to that. It’s very people focused. If you’re a creative or design leader over a much larger team, your number one goal is to have a healthy team with talented folks that you can trust to drive every game. Hopefully then, you can leverage your own abilities and strengths to focus on the areas of the game where you can make an impact. That’s the real high-level theory. The way that actually plays out really depends on a lot of factors. I wish there was a formula to it, but I feel like that’s the closest I can give you.

GamesBeat: Which game do you think forced you to make that transition? If you were talking about those kinds of details with Allen on StarCraft — by World of Warcraft, was that the point where you couldn’t do that anymore?

Pardo: No, not on World of Warcraft. Even on Warcraft III, it got a little challenging to do that exact same level. While I was involved in many aspects of Warcraft III, that game was definitely starting to stretch the scope. We had a level-design team that was doing a lot of great levels on their own. We had a great many units in that game. It was starting to happen there.

By the time you get to World of Warcraft, now there are game systems I’m not able to be as involved in. I’m not able to be involved in every dungeon design. You starting having to have great design leaders driving those things, with high-level feedback and involvement rather than getting to work on every piece of the game every day.

GamesBeat: Are there some concrete examples from your history for people to help them realize what you gain through that extra focus on quality and doing things more carefully?

Pardo: In a lot of ways, quality and excellence — that has to be something that you intrinsically care a lot about. It’s not easy. It can take a lot of work, a lot of heartache. There were many times in my history at Blizzard where we had to kill games, painfully, which is always in that same pursuit. You make it to a place where you have to throw away years of work because it’s just not at that quality standard. That can be really painful. You have to care about finally getting something across the finish line that hits the mark.

GamesBeat: How many times did that happen to you?

Pardo: You know, I don’t know the number, but I would say — we used to jokingly say that our hit rate was probably similar to the rest of the industry. It’s just that we didn’t ship our failures. There were at least as many games killed as there are shipped in Blizzard’s history.

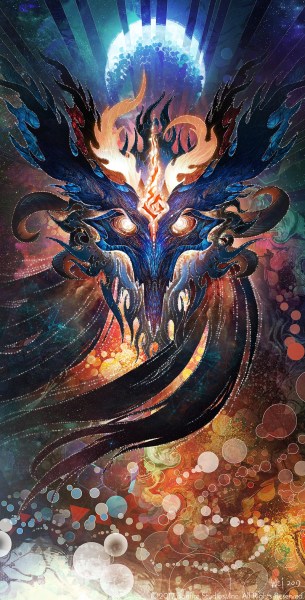

Above: Mask of Dreams.

GamesBeat: I remember the DICE talk where Mike Morhaime talked about that. Had you worked on a lot of those games?

Pardo: Some of them, definitely. Not every one. Again, my history started with StarCraft. There was some stuff I missed in there. Blizzard North had their own list, too. But I think it’s healthy. You look at Supercell recently. They’ve also talked about how they have a very similar philosophy. They’ve definitely killed more games than they’ve shipped.

GamesBeat: That’s one of the only similar companies I’ve seen. I don’t know if there are more than that.

Pardo: There are other companies that are very quality focused. Maybe they don’t talk as much about their philosophies. If I had to guess, I’m sure Valve has had plenty. Maybe they call them experiments rather than games. But I’m sure they’ve had plenty of experiments that haven’t made it out the door.

GamesBeat: Was there something that made it go over better when you have to cancel your game? You could get upset and go start your own thing. Or you could stick around and do the next thing. What was that communication like when that happened?

Pardo: Every situation is different. In most situations, it was team driven. It doesn’t generally happen where someone comes from above and says the game’s getting canceled. It usually happens very slowly and organically. It’s often team driven.

GamesBeat: Did you work on Titan? Did you think it should have kept going, or did you feel like it was time to give up as well?

Pardo: Yes, I was definitely involved in Titan. The biggest thing — first of all, I’m not too comfortable talking about Titan because I’m not at Blizzard anymore, and I don’t want to have a bunch of out-of-context quotes anywhere. But the big thing for me, I think the success of Overwatch shows that it was the right decision. That team went through a very long development process, and maybe the idea of what Titan was didn’t make it out the door, but it turned into Overwatch, which has ultimately been very successful. I’m so happy and proud of the team, that they were able to get that game out.

GamesBeat: Do you have advice for people who are making that kind of decision? “My game’s been canceled. Do I move on or stick around?”

Pardo: It’s way too broad and nuanced of a situation to be able to just casually say, “This is what you should do.” It depends on what the future is and what you want to do next. If you think about anything you might do as a solo creator, you’re probably throwing away work every day. It probably happens to you all the time. You write a story, and it doesn’t come out the way you want to. You toss it in the bin and rewrite it. Any sort of creative process, it happens just like that.

Then, you go to a team-based project, and you’re throwing out work along the way. Canceling a game is just throwing away a team’s work that’s gone really far, to the point where now, other people know it’s a full game. You always endeavor to do all the throwaway stuff early and often and before there’s that much work, but sometimes, it gets really far down the line, and you have to start over.

What often happens with the teams that stay together after you make that is that you learn a lot. We always learn a lot more from our failures than our successes. With more than one game inside of Blizzard, and I’m sure in other companies, that team took all those learnings and immediately went out and made a better game. I know Supercell does that. Blizzard does that. If you have a great studio culture, the right answer is to take those learnings and go make an even more awesome game.

Above: Phoenix.

GamesBeat: Is the end result, the shipment itself, not necessarily the object of excellence? It’s something you do before that?

Pardo: It ends up being both. In the case of a product, there is a day when it’s going to ship, and it’s going to be judged forever by people in the press, by the community, by the team itself. I’m sure people are always going to judge the quality at that point. But the theme of my talk, from a personal creator’s point of view, is to be focused on excellence in the process of your daily work. Don’t get too fixated on what happens once it gets judged by the external world.

GamesBeat: How do you feel about players and player feedback? With the internet now, we have a lot of noise that comes at us. There’s a level of toxicity to it. It’s hard to know what to do or who to listen to among all those critics. How do you deal with that in order to keep doing what you do?

Pardo: I’ve definitely had more than a few incidents with arguments on forums or putting my foot in my mouth. But I think fundamentally, you want to be really player focused. You’re trying to make these entertainment experiences that you want to be enjoyed by as many people as you can. That’s why we’re in it, as artists and creators.

More than anything, I love getting player feedback. Obviously, the way the feedback comes across sometimes is not always the friendliest. You’re going to get people that love your game but talk about the flaws in a way that might make you angry. You might have people who just dislike the game, and they’re going to let you know as well.

For me, I’ve done my best over the years to realize that anyone that’s talking about your game, be it good or bad, means they’re passionate about it. You want to be able to listen to that feedback and internalize it and figure out what you’re going to do about it. It doesn’t always mean you’ll act on every piece of feedback, but don’t be offended by it. If anything, take it as a compliment, even if people are saying bad words. Try to be true to the vision of the game you want to make and synthesize that feedback into something useful.

GamesBeat: What if some of that player feedback becomes contradictory? You see conflicts between different groups of gamers, where one group likes the game to be one way that opposes another.

Pardo: Of course. You’re definitely going to have people who say that’s too hard; this is too easy; that’s just right. You have all different constituencies. That’s why you can’t just go where any given player tells you to go. The development team has to have their own vision for who the audience for their game is. They have to have that very clearly in their mind. Here’s what a player of our game looks like. Here’s how difficult they want it. Here’s the type of world they want.

That has to be very clear to the team before you start listening to feedback. Once you know the audience and the game you’re trying to make, then you can listen to feedback and use that feedback to guide you toward that compass heading. If you’re trying to make an extremely difficult game — the point of the game is to be brutally hard — you know that’s what you’re doing. If a novice player tells you the game’s too easy, you know you’re off your heading, and you can correct toward that. But you have to already know what you want to build and who it’s for. Then, you can use all that feedback.

Above: Mira.

GamesBeat: Did you ever get a common kind of complaint at Blizzard?

Pardo: I don’t know if there was a common complaint, but I can give you a specific example. When we were making World of Warcraft and building the dungeon content, we made the decision where we wanted dungeons to be something you could only accomplish with a group of five different players. That was definitely in a spot in between where some people wanted us to make a lot of raid content, which we weren’t doing yet. We would eventually get to it. And then, you had a fair number of players that were more casual. They wanted to experience the dungeons, but they didn’t want to be forced to group.

We had a very clear vision that we wanted this group-based content. The way we designed the classes and the experience of the bosses in the dungeons was really fun and unique. For us to make that solo-able content, it would undermine what was fun about it in the first place. We stuck true to our philosophy there, even though we had a bunch of people who told us they didn’t want to play in groups but still wanted to experience the story of the dungeons. That’s one example of where we took some heat, but that was the audience we were going for.

GamesBeat: It sounds like a hard topic to give general advice on. “Here’s how you design a game. Here’s how you listen to customers.”

Pardo: The biggest thing about listening to customers and players — you definitely have to listen to the feedback, and you should do your best to communicate your goals and what you’re trying to do, so the player base has a better understanding of your vision and how you’re approaching it. But it’s always going to be challenging. Players range across a spectrum. All you can do is try to be as player focused as possible.

Above: StarCraft Remastered.

GamesBeat: Have you come across other companies that actively promote the opposite of what you’re thinking? “Get it right the first time,” something like that?

Pardo: I don’t know if there’s an opposite. I do think there’s a fair amount of companies out there that may be more deadline driven than they are iteration driven. I don’t want to say “quality driven” because I think every company wants quality. But you have that triangle of, do you want to focus on quality? Do you want to focus on timeliness? Do you want to focus on budget? You can’t really do all three at once. You have to choose one, or maybe you can choose two. But you can’t choose all three.

I do think there are companies that might be more budget and deadline driven, and that makes it hard for you to focus on quality. It doesn’t mean it’s a bad strategy, depending on what your goals are.

GamesBeat: Do you think that this works [for] all kinds of games and game companies? Does it work for mobile-game design, which tends to have smaller teams these days? Or on the largest console game projects?

Pardo: I don’t know if I’m going to go out there and espouse an entire development process. The focus of the talk is more about a way to think about your job, a way to think about your teammates. But when you’re talking about the development process — obviously, I think games and movies or any sort of team-based creative process can focus on excellence. There are going to be differences from team to team and platform to platform, but I think you see excellent products across all of those.

GamesBeat: It seems like the competition is always pretty intense in any segment. You do want to be more focused on quality than the competition or else you wind up with just one game in a million — literally millions in mobile. If you take less time to make your games, odds are your quality isn’t going to reach the right level.

Pardo: If you can make a game at that highest percentage of quality — I don’t know, the top five percent of the market, top 10 percent — I feel like you’ll always stand out. Then competition and timeliness matters less. If you make one of those top games, that’s what people remember.

GamesBeat: Is there a certain type of person you think you need to have on your team to follow this type of philosophy?

Pardo: I don’t know if it’s a type of person. It’s more like alignment with the group. I think that’s what matters most. I think about the spectrum of game developers I’ve worked with. I’ve worked with people that are very different from one another. But the teams made great products because the team was really aligned and driven together. It’s the team alignment that matters more than trying to pick the perfect RPG character stats for any given developer.

At the end of the day, the best teams make the best games. It’s not up to any individual, including myself or any other person you might know by name. It really comes down to having an amazing team that works together, that drives toward a vision. That’s where you get the best products.

GamesBeat: Do you have a takeaway or a conclusion you have planned for the talk?

Pardo: I think it’s to do what you love with people who share a vision. Early in people’s careers, maybe they’re focused on other things, but where I’m at in my career, the way I think about things is I want to work on things I really love and believe in with people that I love coming to work with every day. That’s probably — if you do those things well, then you’ll end up in a pretty cool destination at the end of it.