It’s below freezing in Montreal now, and I’m happy I’m not still there. But for the third year in a row, I enjoyed my recent trip to the Montreal International Game Summit.

The event drew around 2,600 people across dozens of sessions. The closing talks, where prominent developers speak for five minutes each in a session dubbed the MIGS Brain Dump 2017, once again captured the worries and hopes of game developers. This year, they spoke on the topic of “No easy answers,” in a session moderated by Richard Rouse III.

“Sid Meier (creator of Civilization) said that a game is a set of interesting choices with no easy answers,” Rouse said.

Rouse noted the increasing complexity of game development and the sprawling nature of the game marketplace have created problems without obvious solutions. As he curated the talks, he found that some speakers shared an insight that they found to deal with the difficulties, while others set up an issue that the community needs to collectively solve.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Above: Richard Rouse III

Besides Rouse, the speakers included game developers Henry Smith, Rayna Anderson, Osama Dorias, Jason Della Rocca, Rebecca Cohen Palacios, Tanya X Short, Tony Albrecht, and Teddy Dief.

They spoke about how there are no easy answers for the quandaries involved in making games, and how they can muster the resilience needed to finish them.

Henry Smith of Sleeping Beast Games talked about how he wanted to give away his games for free, but still make a basic living. Rayna Anderson of Eidos Montreal spoke about giving honest feedback on games. Osama Dorias of Warner Bros. and Dawson College said there are no easy answers when developers clash about how to make a game, and that it pays to test the character of younger students with no-win situations.

Jason Della Rocca of Execution Labs talked about how to take advantage of entrepreneurial opportunities. Rebecca Cohen Palacios of Ubisoft spoke on making games for her dad, who is nearly blind, by making the controls more accessible. Tanya X Short of Captain Kitfox Games said that games can be made without killing ourselves with too much crunch, or overwork.

Tony Albrecht, a senior engineer at Riot Games, addressed whether games have any social value, as viewed by outsiders who tend to judge them as worthless. And Teddy Dief, creative director at Square Enix, talked about how every choice you make as a developer consumes your energy, and that if you don’t take the proper time to do it, the act itself eventually saps your ability to make the right choices.

Here’s the Brain Dump stories from 2016 and 2015 (parts one and two).

Tony Albrecht, Riot Games

Above: Tony Albrecht, senior game designer at Riot Games shows a slide of That Dragon, Cancer, during his talk at MIGS 2017.

Tony Albrecht related how his aunt asked him 20 years ago about his job in video games. She asked him, “Why aren’t you doing something useful with your life?”

Rhetorically, Albrecht went on to ask a form of that question over and over, even as he showed images of games that are making a difference, like That Dragon, Cancer, which showed what it’s like when death is inevitable, or Re-Mission 2, which gives kids the will to fight cancer.

Above: Tony Albrecht of Riot Games shows an image from Earthlight.

Playing devil’s advocate, he asked whether game developers are making a difference, or if they’re just using their intelligence to make games that rot the minds of kids and fill the developers’ coffers. As he asked these rhetorical questions (like why don’t you do something that educates people or makes them question authority), he showed images from games that addressed exactly what he was talking about, such as a screenshot from Earthlight, a 2015 game that taught people about space.

“You could be training astronauts,” he said in an understated tone. “Are you helping, or are you just making games.”

He showed one game after another that made a contribution, such as SimEarth‘s lessons about global warming. It really was a beautiful talk, and I can’t do it justice with words. Hopefully a video of it will surface soon.

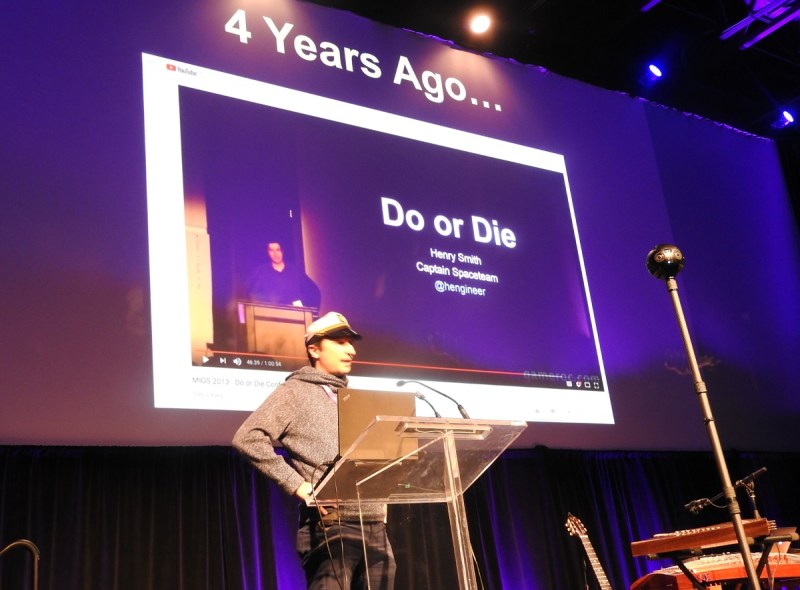

Henry Smith, Sleeping Beast Games

Above: Henry Smith wants to make free games for a living.

Four years, ago, Henry Smith quit his job at BioWare and decided to do an unusual Kickstarter campaign. He wanted to raise $80,000 so he could create video games and launch them for free, for up to one year. He believed that charging money for digital games was broken, free-to-play microtransactions were broken, advertising was broken, and that the real answer was free games.

But he needed to pay the rent. He hoped that countries such as Canada would embrace universal basic income, but they’re not there yet.

The first time, his Kickstarter campaign didn’t hit his goal. But on the second try, he put in more effort and succeeded in raising $83,000. He created Spaceteam, a co-op game where you and your friends fly a spaceship together. It was downloaded more than 5 million times. And it was free.

He was able to make money as companies asked him to create a custom version of the game, and then someone asked to make a board game based on it, and another party asked to put the game into Buffalo Wild Wings restaurants. Smith decided to keep supporting Spaceteam.

“These tentacles formed a big chunk of my income,” Smith said.

Now Smith is working on a new free game dubbed Blabyrinth, which he hopes will be funded through Patreon subscriptions, custom versions, and an in-game tip jar. He hopes to launch it in 2018.

Rayna Anderson, Eidos Montreal

Above: Rayna Anderson of Eidos Montreal

Rayna Anderson, senior narrative designer at Eidos Montreal, has worked on games such as Deus Ex: Mankind Divided. She tackled the question of whether to give truly honest feedback when someone making a game asks you for your opinion of it.

“The question you hear most often in game development is, ‘So, what do you think?'” She said. “Giving good feedback is hard, if not impossible, to do. As game developers, we get too close to our creations and the feedback we get from outsiders can orient us.”

But if you tell the honest truth, you might very well discourage people from finishing their games.

“Feedback is not about convincing someone that your point of view is the right one,” she said. “That’s not what they wanted and not what they needed from me. If you tell someone what to do, they will do it, especially hearing it from someone with authority. Feedback is an invitation to participate in someone else’s creative effort.”

When you give feedback, she concluded, you should not give easy answers. It’s a responsibility you should not take lightly. And so you should figure out instead how you can make that person reach their goals.

Osama Dorias, Warner Bros.

Osama Dorias is a senior game designer at Warner Bros. and teaches at Dawson College.Osama Dorias, who coordinates the video game program at Dawson College, talked about “the double jump scenario.” He and his partner Salim Larochelle devised a scenario that they posted to young game developers.

A game is being built by a team of three people who are equal partners. The programmer hates double jumps. You, as the designer, want the double jumps. And an artist says you should playtest it. You ask the programmer to create a test version, and he refuses.

“It is our version of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan‘s Kobayashi Maru simulation,” which is basically a no-win situation, Dorias said.

The interviewees in the scenario have to figure out how to solve the situation. The answer from the programmer is always the same. The point is to test the character of the students, to see if they can empathize with the programmer, to frame the project as a team effort, and see it from another view.

“They always ask if there is an answer, and we say there aren’t always easy answers when it comes to interacting with others,” Dorias said. “The double jump scenario was meant to draw out how interviewees react to a really common thing that we often encounter.”

Rebecca Cohen Palacios

Above: Rebecca Cohen Palacios wants games to be more accessible for her nearly blind father.

Rebecca Cohen Palacios is a user interface artist at Ubisoft Montreal and cofounder of the women’s incubator group Pixelles. She worked on Assassin’s Creed Origins, and she talked about how she wanted everybody to make games for her father.

She said she is a fierce advocate for diversity and inclusion, and her dad loves games such as Madden NFL Football, racing, and online shooters. They play games together.

But her father is nearly blind. How do you design a video game for someone who is nearly blind? Or perhaps color blind?

Players over 50 are 26 percent of the gaming population. They are not the core audience. But we’re all going to get older and eventually develop eyesight problems. Should we stop playing games? No, said Cohen Palacios.

“It’s 2017, and we can definitely do more,” she said. “We can find beautiful solutions that work.”

You can use bigger fonts in games. Or add modes that have deeper contrasts. You can explore ideas in the Includification site.

“It’s going to be hard, but it’s only hard because we only design in one way,” she said.

Jason Della Rocca

Above: Jason Della Rocca talks about making your game viable at MIGS 2017.

Jason Della Rocca, cofounder of Execution Labs and former head of the International Game Developers Association, talked about what he learned as an early-stage investor in game studios.

He found that many game developers were wrestling with identity issues, as to whether they viewed themselves as entrepreneurs or starving artists, as exemplified in Indie Game: The Movie. How do you create something innovative and fun that is also commercially viable?

Indies should not view their art romantically, as something pure that should not be sullied by business. If you see your challenges as a bunch of problems, with the lack of money as the main problem. If you look everywhere for help, you may find, Della Rocca said, “Unfortunately, the rest of the world doesn’t care. Zero fucks are given. It’s cruel and it’s mean to say. But at the end of the day, hope is not a valid business model.”

But you can turn the situation around and view it from another perspective. Della Rocca said there are four lessons to remember.

1. Some truth: A great game is the starting point, not the end.

2. Building a fan base and community is as important as building a great game.

3. The business model design has to be intentional and player focused.

4. Stop pitching problems, only work on true opportunities.

“You have to believe that what you are doing is an opportunity, and that you are not just trying to solve a set of problems,” Della Rocca said. “Think of these lessons and make an amazing great game and you will make it commercially viable at the same time.”