By now you’ve likely seen this week’s The Economist cover story titled “Peak Valley,” which features quotes from Claire Haidar. She is CEO of WNDYR, an Intelis Capital portfolio company. The article highlights outrageous costs of living, poor local government, and high operating costs as the catalysts behind an impending Silicon Valley collapse.

We’re skeptical that Silicon Valley is “over.” However, we do see its influence dwindling in the next few decades as a direct result of a technological invasion into new sectors that drive the economies of other regions.

Every industry is a technology industry

It should come as no surprise by now that almost every industry has come to rely on technology for some core part of its operations. Yet there is a large variance in the degree of digitization across sectors that are cornerstones in regional economies outside of the Valley — sectors that have largely been ignored by coastal VCs until the past couple of years.

Industries like energy, agriculture, construction, and manufacturing are lagging behind the innovation curve and represent a multi-trillion dollar opportunity for startups and investors alike. Their importance to regional economies like Texas, the Southeast, and Midwest can’t be overlooked.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

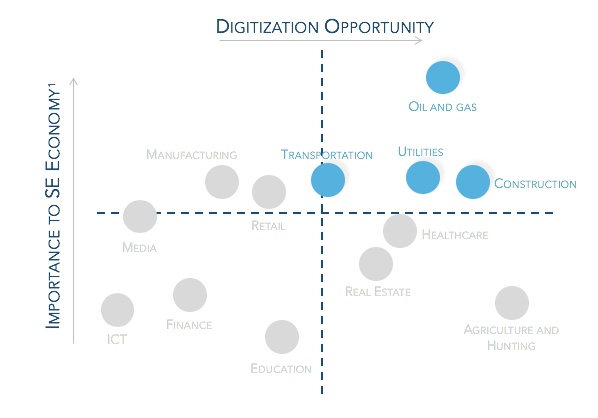

We used the Bureau of Economic Analysis geographical definition of the Southeast, as well as Texas, for our analysis for the graph above. We then measured that against an industry’s opportunity for “digitization” based on research from McKinsey. Sectors such as power utilities (which makes up 5.2 percent of the Southeast’s GDP), oil & gas (2.54 percent), transportation (3.43 percent), and construction (4.83 percent) contribute much more to the regional economy than in the U.S. as a whole. While these percentages look may look small, it’s important to note the size of the U.S. economy was $18.5 trillion in 2016, and the Southeast region accounts for about one third of total U.S. GDP.

The ability to build software products is without a doubt Silicon Valley’s competitive advantage, made possible by an unmatched density of engineering talent. Yet because the aforementioned sectors are largely undigitized, only a minimal level of improvement is necessary in order to replace current analog processes. Thanks to the spread of technology, the requisite level of engineering talent can now be found, for less money, in most metropolitan areas.

Additionally, distribution of product is sometimes just as important, if not more so. The density of customers and potential partners in other regions provides startups with a ready-made strategy to build revenue from the outset.

These advantages can result in the healthier profit-and-loss statements highly valued by potential acquirers in these sectors, leading to exits that drive ecosystem growth.

Founder/market fit

There’s a reason these analog industries have yet to be disrupted. Often they require highly skilled and specific knowledge, are encumbered by regulation, have entrenched bureaucracy throughout the entire value chain, or — in the worst cases — all three.

Witnessing first-hand the ways an industry is broken is crucial to building the foundation of a big business within them. More importantly, it removes any naivete a founder might have and prepares them for the potential roadblocks ahead. A few obvious and successful examples of this are Flexport (freight), Robinhood (finance), and Farmers Business Network (agriculture).

Before, entrepreneurs would have had to move to Silicon Valley to start these companies due to lack of local resources and talent. However, an explosion of cloud-based collaboration and communication software has now made it possible for these executives to tie into specialized talent from the Valley if and when needed.

Moving to the Valley as a contingent of funding is becoming less common as distributed work becomes more of an accepted practice, and the rise of new firms focused specifically on not investing on the coasts has given founders more access to capital than ever before. This combination has solved one of the biggest problems of building a business outside of Silicon Valley: access to capital.

It’s clear there are several new sectors and regions are primed for the necessary disruption heading in their direction. Undoubtedly, Silicon Valley will play a direct or indirect role in many of the advances, but for the first time ever that role may not be from the driver’s seat.

Kevin Stevens is a partner at Intelis Capital, a new early-stage VC firm based in Dallas, Texas. A version of this post first appeared on his blog.