Merry Christmas and happy holidays. I thought I would do something different for a holiday message this year. It’s based on a talk I gave to a game journalism class at Stanford University recently. It’s about my life in game journalism, and how I got to where I am today. I hope you enjoy it.

I am a quiet person in general. It takes me a little while to find my voice when I’m talking. I ask that you be a bit understanding on that. I like to write at night when I have more time to think about things. I enjoyed this book by Susan Cain called Quiet: The power of introverts in a world that just can’t stop talking. It helped me understand and come to terms with being a quiet person in a very noisy environment like game journalism.

Above: Quiet is a book that will make you feel at home with your quiet nature.

You can judge how old I am because I was around as a kid when the original Pong came out in 1971. I played it for the first time in a luxury setting at the tennis courts at the Tropicana hotel when my family was on vacation. My brother and I went into the lounge for the tennis courts. It was very fancy, and they had these tables. The tabletops were machines that had Pong in them. We put a lot of quarters into that.

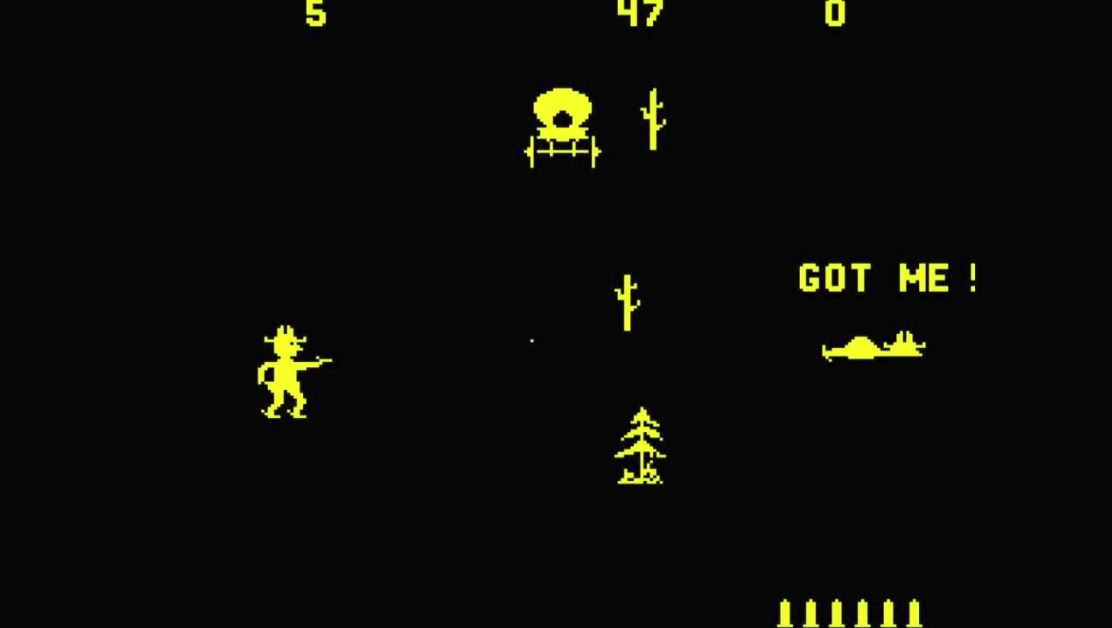

I grew up in Sacramento. We played a game called Gun Fight at the local sandwich shop. It was a one-on-one shootout game. You can tell by the quality of the graphics how old that is. I had an Intellivision at home. I didn’t have a lot of other consoles, but I was always in the arcades. I read Strategy and Tactics magazine, played war games on paper, and immersed myself into the artificial worlds of books like Tolkien and Dune. But games were something different for me. They let me use my imagination more, I thought, and tell my own stories each time I played. I’d play it over again, and it would be a different story, like an interactive novel.

Above: Gun Fight

In college at Berkeley I became an English major. I got a job as a copy aide at the Institute for Journalism Education. They had the Summer Program for Minority Journalists there. They took people who had no experience in journalism, minorities, and they trained them for 10 weeks over the summer and then put them into jobs at newspapers. They did this because they felt like it was a mission for diversity. At the time, about 94 percent of the journalists in the U.S. were Caucasian. Six percent were minorities. I think about 20 percent of the country was minorities by contrast. They felt, to better reflect what was happening in minority communities and the nation as a whole, you needed a more diverse journalistic workforce. This was affirmative action for journalists. I was the copy aide, just proofreading copy, delivering newspapers, developing film, and hanging out at Northgate Hall at UC Berkeley.

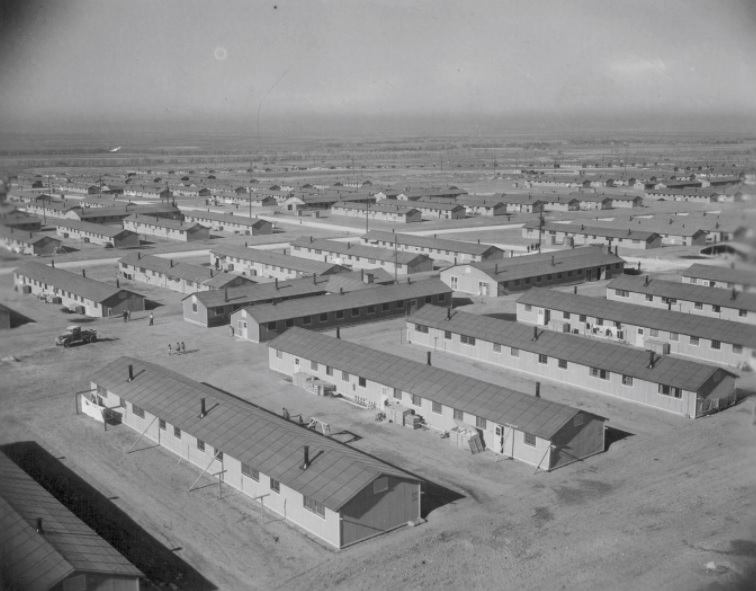

I mentioned being quiet. Sometimes people can be too quiet, to their own detriment. The Japanese Americans were rounded up in World War II, and most did not protest overtly at the time. Japanese-American internment shaped my identity, and it led me to journalism. You could say, in this modern phrase, that I was a “social justice warrior” as far as the reason why I got into journalism.

In 1991 I was at the L.A. Times. The newspaper dismissed my initial pitch, and then they wrote a series of stories about the 50th anniversary of Pearl Harbor. It was what you would expect, I guess, for a newspaper to do. I pitched these stories again in February of 1992, when another anniversary, of the Executive Order 9066, came around. That order put Japanese-Americans, and my family, into internment camps.

Above: The internment camp in Poston, Arizona.

I visited one of those camps for the story. I re-imagined what it was like to have been in those camps back in the 1940s, when nothing but wind and dust were blowing around. One of the internees I interviewed later, he said that being in these barracks, with one-inch openings in the pieces of wood, was like having sand blown at you with a fire hose. In the middle of the night, the sentence that kicked off that series came to me. It was, “Fifty years ago here, the only thing free to come and go as it pleased was the wind.”

Above: No Justice

My 17-year-old daughter has picked up on some of these things over time. She created an image. It is a picture of Japanese American internees with name tags, superimposed on the Department of Justice. The lettering there says “No justice.” On one of the pillars it says, “I became a journalist because of internment.” She did this because she found an old speech I gave, way back in the 1990s. She put the lettering of the speech all over the stone. I thought it was a cool piece of art and I’m proud of her for creating it.

I got a master’s degree in journalism at Northwestern, and I got my first job at the Dallas Times-Herald newspaper, which no longer exists. I started covering tech companies in Dallas. I moved to Los Angeles. My brother lived in that city. I covered tech at the L.A. Times in Orange County. I bought a 486 PC to play PC games. I only learned enough about technology at the time in order to play games. If you had to create a boot disk to play something like A-10 Tank Killer, I would do everything I could, and then once I was able to do that, I stopped learning.

Above: Blizzard’s early team.

I wrote one of the first stories about Blizzard Entertainment, when they were known as Chaos Studios. They sold their company for a very small amount of money these days, $7 million or something, to Davidson and Associates, but went on to be very successful. The president of Blizzard, Mike Morhaime, recently said to me, “Thank you for 25 years of good coverage.” I covered Brian Fargo of Interplay, and still cover him today. He’s about to retire. I’m not quite ready to do that.

Most of my job has been covering tech companies, in all of these previous positions here. Games were not enough of an industry to be a real beat at a mainstream newspaper. That was the reality of things. I would play Dr. Mario at parties, at my brother’s house. He would have friends come over and we’d have four TVs with four consoles going at once, a total of eight people playing at a time. Everybody was yelling at each other to win.

Above: Video shot by George Holliday shows police officers beating a man, later identified as Rodney King.

The L.A. riots happened while I was at the Times in 1992. Having come from Berkeley and the minority journalism program, I was fairly conscious about diversity. I was president of the local chapter of the Asian-American Journalists Association at the time. It fell on me to speak up about it, to say, “Hey, you know, the L.A. Times has done some outstanding work here. They won a Pulitzer Prize for the coverage of the riots. But inside the newspaper a lot of people are unhappy.” It came as such a blindside surprise to everybody. The percentage of minorities in the L.A. Times staff, covering the communities of color in Los Angeles, was not so good.

We spoke up about it. A lot of people at the time said my career in journalism was over, because I’d criticized my bosses. But it’s a democracy, right? We have freedom of speech and freedom of the press. For a newspaper to crack down on someone like me, because I spoke up and criticized it, would have been the ultimate hypocrisy. The editor at the time, Shelby Coffey, actually agreed with that. So he didn’t fire me. I thought that was great.

Above: Tracy Takahashi

In 1993 my brother was murdered. It happened because of a rivalry between two gangs where he lived in Los Angeles. One of the gangs was going after another gang’s member. In the middle of the night they knocked on the door of a house and shot the guy who opened it. They went to the wrong house. It was my brother’s house. And so he was gone.

This had a devastating effect on me. I couldn’t play violent video games for a while. They were too close to reality. I couldn’t stand the sound of gunfire. Now, they caught these guys. One guy was 17 and two of them were 18 at the time. They were convicted, the two older ones. They were put away for life in prison. I wrote a letter to the judge when they were sentenced. I said, “Life is not like a video game. You don’t get a second chance when you’re shot. The choices you make are important.” In that letter, I mentioned that they should turn their lives around, whether they were in jail or not. Many years later, a reporter at the LA Times called me to tell me one of them was up for parole. He had taken my words to heart from so long ago, and he had become a hospice worker inside the prison, tending to the dying prisoners. He had chosen to turn his life around.

I like this quote from Kurt Vonnegut Jr., the author of Mother Night. Mother Night is a book about an American spy who poses as a Nazi propagandist. He’s a lousy spy, and he’s too good at his job as a propagandist. And so you have to wonder, what was your purpose in life? What did you do? I like to think about this when you apply it to games as well.

Above: Mother Night

I don’t want to put too heavy a burden on game developers. But I think it’s good to think about the interplay about fantasy and reality in your games. I once interviewed Bruce McMillan, an executive at Electronic Arts. He said, “You may only get 10 games to work on in your life. If each one takes three years to make, 30 years, 10 games, that’s all you get. Each one you work on should be special in some way.” Your games should be special.

Time went on. I met the love of my life. I got married. We had our first child. I played games like Gettysburg and Shiloh, which were reasonably non-violent, considering the subject matter. My kid would be on my lap and I’d play these games. I moved to Silicon Valley in 1994. That was the year Netscape went public. I started covering chips for the San Jose Mercury News. That started me on this path to be immersed in Silicon Valley and tech for the last 25 years or so.

Above: Battleground 4: Shiloh

I switched to the Wall Street Journal in 1996. At the time I was in the San Francisco bureau. I would substitute for Walt Mossberg. He never played any computer games. So I would do the occasional review on games like Warbirds when he went on vacation. Since I was the youngest guy in the office and the only guy who played game, they said, “Do you want to cover games like Nintendo and Sega and EA?” I said, “Yeah, sure.” It was an interesting way to start looking at the industry on a day to day basis, because I was a business journalist at the Wall Street Journal, trying to find ways to convey what this industry was like to people who mostly did not play games.

I eventually moved to Red Herring magazine. I wrote a book on the making of Microsoft’s first game console. The book was called Opening the Xbox. This was inspired by Tracy Kidder’s Soul of a New Machine, which is a book about the general and a couple of teams that were competing with each other to create the next great computer. It really made you feel like a fly on the wall. I tried to interview as many people as I could officially and unofficially for this book to really give the flavor of what it was like to work on a game console.

I got laid off from the Red Herring and returned to the San Jose Mercury News. The tech bubble burst. I wrote a book on the Xbox 360 — The Xbox 360 Uncloaked — and started writing a lot more about games. Mike Antonucci was my colleague. I would do gaming podcasts with him at the Mercury News.

Above: Grand Theft Auto IV

These are some things that come to mind in game journalism. You don’t want to entirely rely on the public relations people and what they tell you about what a company’s doing. You have to have a wide variety of sources. I’ll talk more about this subject later. When I was writing the book I had this chance to ask a lot of people, 100 people, about the same events that happened. Sometimes, where these stories intersect, you get a pretty good idea that what you’ve heard is the truth. But sometimes you get this spaghetti of different stories, with disputes between people about what happened and flawed memories and things like that. Journalism is a muddy thing. It’s not always a science.

The interesting thing about covering games and playing games is that I returned to playing violent games again. But I always wanted to be the good guy, the person who’s doing good in the world of the game. And so I had a real problem with Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto series, where all you get to do is mayhem. At some point, by the fourth installment, I could appreciate how cinematic these games were getting. They were very movie-like. They’re telling stories about what it’s like to be people who are not like you. You can walk in their shoes. As long as you have this ability to distinguish between fantasy and reality, and you’re responsible enough to do that, then why not go ahead and play these games?