Merry Christmas and happy holidays. I thought I would do something different for a holiday message this year. It’s based on a talk I gave to a game journalism class at Stanford University recently. It’s about my life in game journalism, and how I got to where I am today. I hope you enjoy it.

I am a quiet person in general. It takes me a little while to find my voice when I’m talking. I ask that you be a bit understanding on that. I like to write at night when I have more time to think about things. I enjoyed this book by Susan Cain called Quiet: The power of introverts in a world that just can’t stop talking. It helped me understand and come to terms with being a quiet person in a very noisy environment like game journalism.

Above: Quiet is a book that will make you feel at home with your quiet nature.

You can judge how old I am because I was around as a kid when the original Pong came out in 1971. I played it for the first time in a luxury setting at the tennis courts at the Tropicana hotel when my family was on vacation. My brother and I went into the lounge for the tennis courts. It was very fancy, and they had these tables. The tabletops were machines that had Pong in them. We put a lot of quarters into that.

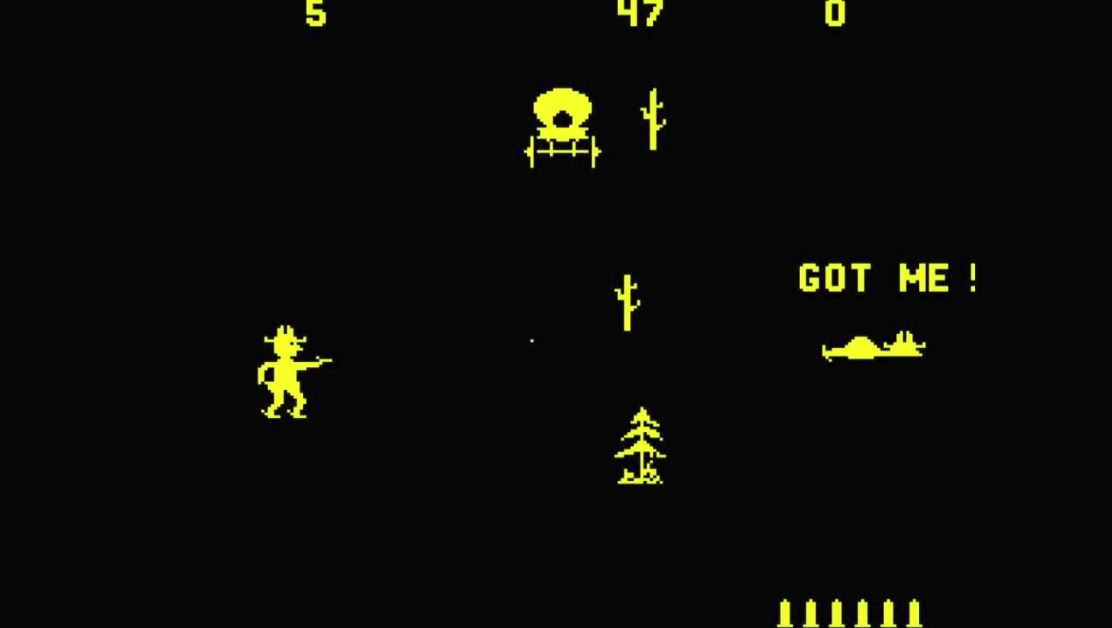

I grew up in Sacramento. We played a game called Gun Fight at the local sandwich shop. It was a one-on-one shootout game. You can tell by the quality of the graphics how old that is. I had an Intellivision at home. I didn’t have a lot of other consoles, but I was always in the arcades. I read Strategy and Tactics magazine, played war games on paper, and immersed myself into the artificial worlds of books like Tolkien and Dune. But games were something different for me. They let me use my imagination more, I thought, and tell my own stories each time I played. I’d play it over again, and it would be a different story, like an interactive novel.

Above: Gun Fight

In college at Berkeley I became an English major. I got a job as a copy aide at the Institute for Journalism Education. They had the Summer Program for Minority Journalists there. They took people who had no experience in journalism, minorities, and they trained them for 10 weeks over the summer and then put them into jobs at newspapers. They did this because they felt like it was a mission for diversity. At the time, about 94 percent of the journalists in the U.S. were Caucasian. Six percent were minorities. I think about 20 percent of the country was minorities by contrast. They felt, to better reflect what was happening in minority communities and the nation as a whole, you needed a more diverse journalistic workforce. This was affirmative action for journalists. I was the copy aide, just proofreading copy, delivering newspapers, developing film, and hanging out at Northgate Hall at UC Berkeley.

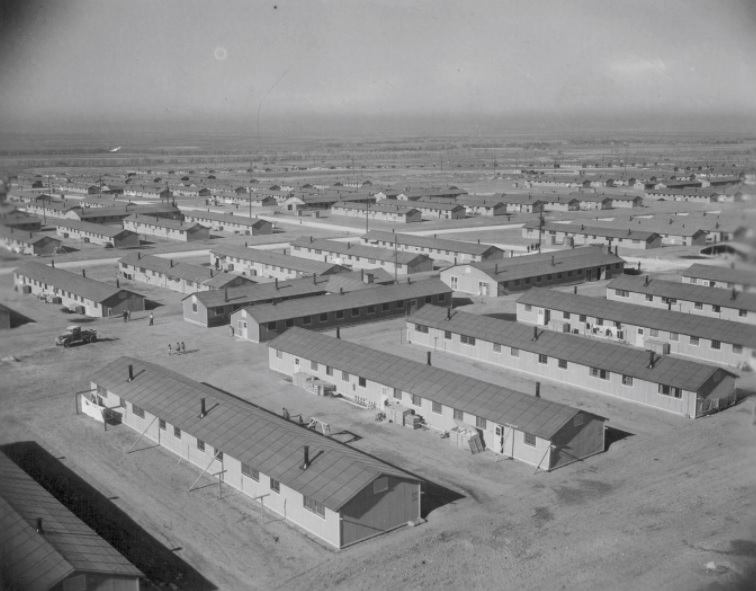

I mentioned being quiet. Sometimes people can be too quiet, to their own detriment. The Japanese Americans were rounded up in World War II, and most did not protest overtly at the time. Japanese-American internment shaped my identity, and it led me to journalism. You could say, in this modern phrase, that I was a “social justice warrior” as far as the reason why I got into journalism.

In 1991 I was at the L.A. Times. The newspaper dismissed my initial pitch, and then they wrote a series of stories about the 50th anniversary of Pearl Harbor. It was what you would expect, I guess, for a newspaper to do. I pitched these stories again in February of 1992, when another anniversary, of the Executive Order 9066, came around. That order put Japanese-Americans, and my family, into internment camps.

Above: The internment camp in Poston, Arizona.

I visited one of those camps for the story. I re-imagined what it was like to have been in those camps back in the 1940s, when nothing but wind and dust were blowing around. One of the internees I interviewed later, he said that being in these barracks, with one-inch openings in the pieces of wood, was like having sand blown at you with a fire hose. In the middle of the night, the sentence that kicked off that series came to me. It was, “Fifty years ago here, the only thing free to come and go as it pleased was the wind.”

Above: No Justice

My 17-year-old daughter has picked up on some of these things over time. She created an image. It is a picture of Japanese American internees with name tags, superimposed on the Department of Justice. The lettering there says “No justice.” On one of the pillars it says, “I became a journalist because of internment.” She did this because she found an old speech I gave, way back in the 1990s. She put the lettering of the speech all over the stone. I thought it was a cool piece of art and I’m proud of her for creating it.

I got a master’s degree in journalism at Northwestern, and I got my first job at the Dallas Times-Herald newspaper, which no longer exists. I started covering tech companies in Dallas. I moved to Los Angeles. My brother lived in that city. I covered tech at the L.A. Times in Orange County. I bought a 486 PC to play PC games. I only learned enough about technology at the time in order to play games. If you had to create a boot disk to play something like A-10 Tank Killer, I would do everything I could, and then once I was able to do that, I stopped learning.

Above: Blizzard’s early team.

I wrote one of the first stories about Blizzard Entertainment, when they were known as Chaos Studios. They sold their company for a very small amount of money these days, $7 million or something, to Davidson and Associates, but went on to be very successful. The president of Blizzard, Mike Morhaime, recently said to me, “Thank you for 25 years of good coverage.” I covered Brian Fargo of Interplay, and still cover him today. He’s about to retire. I’m not quite ready to do that.

Most of my job has been covering tech companies, in all of these previous positions here. Games were not enough of an industry to be a real beat at a mainstream newspaper. That was the reality of things. I would play Dr. Mario at parties, at my brother’s house. He would have friends come over and we’d have four TVs with four consoles going at once, a total of eight people playing at a time. Everybody was yelling at each other to win.

Above: Video shot by George Holliday shows police officers beating a man, later identified as Rodney King.

The L.A. riots happened while I was at the Times in 1992. Having come from Berkeley and the minority journalism program, I was fairly conscious about diversity. I was president of the local chapter of the Asian-American Journalists Association at the time. It fell on me to speak up about it, to say, “Hey, you know, the L.A. Times has done some outstanding work here. They won a Pulitzer Prize for the coverage of the riots. But inside the newspaper a lot of people are unhappy.” It came as such a blindside surprise to everybody. The percentage of minorities in the L.A. Times staff, covering the communities of color in Los Angeles, was not so good.

We spoke up about it. A lot of people at the time said my career in journalism was over, because I’d criticized my bosses. But it’s a democracy, right? We have freedom of speech and freedom of the press. For a newspaper to crack down on someone like me, because I spoke up and criticized it, would have been the ultimate hypocrisy. The editor at the time, Shelby Coffey, actually agreed with that. So he didn’t fire me. I thought that was great.

Above: Tracy Takahashi

In 1993 my brother was murdered. It happened because of a rivalry between two gangs where he lived in Los Angeles. One of the gangs was going after another gang’s member. In the middle of the night they knocked on the door of a house and shot the guy who opened it. They went to the wrong house. It was my brother’s house. And so he was gone.

This had a devastating effect on me. I couldn’t play violent video games for a while. They were too close to reality. I couldn’t stand the sound of gunfire. Now, they caught these guys. One guy was 17 and two of them were 18 at the time. They were convicted, the two older ones. They were put away for life in prison. I wrote a letter to the judge when they were sentenced. I said, “Life is not like a video game. You don’t get a second chance when you’re shot. The choices you make are important.” In that letter, I mentioned that they should turn their lives around, whether they were in jail or not. Many years later, a reporter at the LA Times called me to tell me one of them was up for parole. He had taken my words to heart from so long ago, and he had become a hospice worker inside the prison, tending to the dying prisoners. He had chosen to turn his life around.

I like this quote from Kurt Vonnegut Jr., the author of Mother Night. Mother Night is a book about an American spy who poses as a Nazi propagandist. He’s a lousy spy, and he’s too good at his job as a propagandist. And so you have to wonder, what was your purpose in life? What did you do? I like to think about this when you apply it to games as well.

Above: Mother Night

I don’t want to put too heavy a burden on game developers. But I think it’s good to think about the interplay about fantasy and reality in your games. I once interviewed Bruce McMillan, an executive at Electronic Arts. He said, “You may only get 10 games to work on in your life. If each one takes three years to make, 30 years, 10 games, that’s all you get. Each one you work on should be special in some way.” Your games should be special.

Time went on. I met the love of my life. I got married. We had our first child. I played games like Gettysburg and Shiloh, which were reasonably non-violent, considering the subject matter. My kid would be on my lap and I’d play these games. I moved to Silicon Valley in 1994. That was the year Netscape went public. I started covering chips for the San Jose Mercury News. That started me on this path to be immersed in Silicon Valley and tech for the last 25 years or so.

Above: Battleground 4: Shiloh

I switched to the Wall Street Journal in 1996. At the time I was in the San Francisco bureau. I would substitute for Walt Mossberg. He never played any computer games. So I would do the occasional review on games like Warbirds when he went on vacation. Since I was the youngest guy in the office and the only guy who played game, they said, “Do you want to cover games like Nintendo and Sega and EA?” I said, “Yeah, sure.” It was an interesting way to start looking at the industry on a day to day basis, because I was a business journalist at the Wall Street Journal, trying to find ways to convey what this industry was like to people who mostly did not play games.

I eventually moved to Red Herring magazine. I wrote a book on the making of Microsoft’s first game console. The book was called Opening the Xbox. This was inspired by Tracy Kidder’s Soul of a New Machine, which is a book about the general and a couple of teams that were competing with each other to create the next great computer. It really made you feel like a fly on the wall. I tried to interview as many people as I could officially and unofficially for this book to really give the flavor of what it was like to work on a game console.

I got laid off from the Red Herring and returned to the San Jose Mercury News. The tech bubble burst. I wrote a book on the Xbox 360 — The Xbox 360 Uncloaked — and started writing a lot more about games. Mike Antonucci was my colleague. I would do gaming podcasts with him at the Mercury News.

Above: Grand Theft Auto IV

These are some things that come to mind in game journalism. You don’t want to entirely rely on the public relations people and what they tell you about what a company’s doing. You have to have a wide variety of sources. I’ll talk more about this subject later. When I was writing the book I had this chance to ask a lot of people, 100 people, about the same events that happened. Sometimes, where these stories intersect, you get a pretty good idea that what you’ve heard is the truth. But sometimes you get this spaghetti of different stories, with disputes between people about what happened and flawed memories and things like that. Journalism is a muddy thing. It’s not always a science.

The interesting thing about covering games and playing games is that I returned to playing violent games again. But I always wanted to be the good guy, the person who’s doing good in the world of the game. And so I had a real problem with Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto series, where all you get to do is mayhem. At some point, by the fourth installment, I could appreciate how cinematic these games were getting. They were very movie-like. They’re telling stories about what it’s like to be people who are not like you. You can walk in their shoes. As long as you have this ability to distinguish between fantasy and reality, and you’re responsible enough to do that, then why not go ahead and play these games?

Above: Opening the Xbox

I moved to VentureBeat in 2008. I thought, “Okay, I guess we’re covering startups, we’re covering the venture capital community, I probably won’t write any more game stories.” That turned out to be quite wrong. The game startups, they proliferated with Facebook and apps in 2008. We threw our first game conference during GDC that year and 600 people showed up. VentureBeat was in business covering games. Because of that I got to spend 80 percent of my time covering games. 20 percent is everything else in Silicon Valley.

In 2009 I wrote this story, about the Red Rings of Death. Sometimes you would like to be able to do nothing but this kind of work, where you’re unearthing things. Things like how much warning they had that this was coming, and how they decided to ship the console anyway, because they had to beat Sony out the door this time. The last time around, in the previous launch of the Xbox, Sony had sold 25 million units of the PlayStation 2 before Microsoft sold a single Xbox. Microsoft was in a rush the second time around, and this was what happened.

Games are actually, according to market researcher Newzoo, a $116 billion business in 2017. $50 billion of that is mobile games.

In 2011 I got my kid a flu shot, and my kid got the flu, and then I caught the flu from her, and I got pneumonia after. I had nothing to do for a while, and I couldn’t talk to people, so I just wrote. I wrote these two ebooks. A high point was writing about Blizzard’s cancellation of Titan before anyone else did, but I’ve also made some giant mistakes in my career, like erroneously reporting that Google acquired Twitch when in fact it was Amazon. Google was talking to them, but turned off the talks at some point.

Above: Dean Takahashi at a GamesBeat conference.

GamesBeat now has a staff of seven game-related writers and editors, not including the tech writers that cover tech for the rest of VentureBeat. This is where I am on social media. It’s interesting that 25 percent of my Twitter followers are fake. I’m not sure how that happens or how to get rid of them. I didn’t buy those followers. Who knows how that happens. But social media is far more a part of my daily job than it ever was before. We write a story. Sometimes it’s like a tree falling in the forest and nobody reads it. You have to share your story and figure out ways to get it in front of people. We’re part of this whole attention economy as journalists.

But before I get a big head, the people who create games are probably more like the real celebrities of our industry, like John Carmack, who has more than 800,000 followers.

This is my tally. My analytics tell me that I’ve done 15,000 stories in almost 10 years at VentureBeat, 29 stories a week. That’s pretty tiring. But I only do maybe a dozen game reviews a year. A lot of that is writing the day to day business of games and technology companies. I think of it as a lot of people I’ve met.

Above: The Last of Us is one of several recent big-budget games to feature a LGBT character.

The Last of Us is my favorite game. I read Malcolm Gladwell’s outliers, and yeah, I’ve put my 10,000 hours into games, many more times than that. It raises the question, am I a gamer?

Gamergate came along in 2014. In 2014, it seemed like the real theme of Gamergate was, “Let’s harass women in the industry.” That was the media take. It seemed like it was purely about sexual harassment. We had a blind spot here, because we have been wrong when covering other media outlets before and so we had a rule of not writing about other media. Let’s not write about ourselves. We’re not that interesting. Let’s write about tech companies.

So this big story that affects the media comes along, and we stayed silent on this for weeks. We didn’t really weigh in on it until Intel stepped in a big pile of crap. Basically caved into Gamergate critics and decided to pull advertising out of Gamasutra, because their critics were complaining about Leigh Alexander, a woman columnist, who was too strident a feminist. Intel caved. They realized they made a mistake. And it started spreading through the industry. We started writing about it a lot more. I wrote a column about how stupid this is, how it’s bad to harass women in the industry. Even though I took a stand like that, the Gamergaters never came after me. They never came after male journalists or game developers. They went after outspoken women game developers.

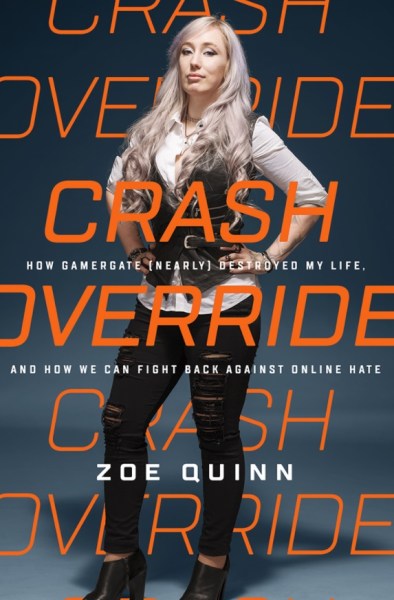

Above: Zoe Quinn’s book Crash Override chronicles her Gamergate experience and how she is fighting back.

I’ll talk about something else that happened this year in a bit, but I interviewed Zoe Quinn about her Gamergate experience and her book that came out this year. I also talked to critics of my own in the Kotaku in Action subreddit, which you would define as pro-Gamergate. And so I got a dose of their attention this year, all because of game journalism ethics issues. They had claimed that this was what this was all about, back in 2014.

It does make you think about how you cover things, as someone focused on the industry here. You can be an outsider as a journalist, being objective as you look at an industry and trying to cover it as best you can. But you can also be an insider getting scoops on the industry from people who you know well, people you trust, your friends. That makes you a good journalist as well. But you do have to go between being an outsider and being an insider as a journalist. That’s one of the best things about the job, and if you don’t take advantage of that, you’re not doing your job right. I think it’s a great way to see things from a different perspective that nobody else sees.

I think it’s good for everyone to ask, “What’s your blind spot?” Editors would ask me, in the early days of game journalism, if I had gone native by being too friendly to the companies I was covering. Gamers now, after Gamergate, started asking the same questions, about whether game journalists are too friendly to game companies. The dot-com bubble—tech journalists maybe didn’t scrutinize these crazy companies that were coming out.

Above: The Internet Bubble

Maybe that bubble would have happened anyway, but it was funny. I worked at the Red Herring at the time. The owners of the Red Herring wrote a book called The Internet Bubble. It was a pretty good book warning about what was coming, but their own company wasn’t positioned for that eventual collapse. The Red Herring under that ownership went out of business, even though the owners foresaw what was happening there. It seemed like an unavoidable fate.

You can think of this difference of inside and outside as being the trade press versus the mainstream press. At the trade press you may pick up better rumors, but do you just go ahead and print them? The mainstream press has a lot of standards for figuring out what the truth is. I think I’ll pause here and say, “Do you guys have any questions?”

I think back to my history, about the Vietnam War. It really does show you how the change you have in perspective, and the diversity of your sources, and whether you’re getting all points of view or not, or if you’re selectively choosing the information and facts you want to present, deciding the truth is a very simple thing — in the Vietnam War, places like Time Magazine, they had their reporters who were witnessing the war in the field writing very skeptical stories about who was winning. And in Washington D.C. they had the bosses of these people overruling them and writing more optimistic stories based on sourcing they had with the Pentagon. You can see why it’s important to have this ability to go back and forth between outside and inside.

Journalistic ethics do matter. If we get free stuff, free trips, we should disclose that. We take long-term loans for consoles, and we disclose that. Some machines that are maybe too expensive for us to buy, we borrow them. We disclose that. If we take trips from groups, trade associations, we disclose that when we’re writing about something that happens at their events, but we don’t take free trips from companies. That’s VentureBeat’s policy. The games press will not have all the same policies, the trade press.

Above: PewDiePie doesn’t want to be considered with Nazis, but his language isn’t helping.

A lot of people get their information from people like this. You remember my followers were in the thousands. PewDiePie is doing a little better than me when it comes to followers in the millions. He’s not a quiet person. He made jokes that made him seem like a Nazi sympathizer, but nobody’s perfect. This draws the distinction between influential people in the industry. On one side you do have journalists. On the other side it’s a new game. Game journalism is changing. You guys asked how game journalism is changing. Well, these people known as influencers are in the picture now. They’re more like personalities and entertainers than they are journalists. They can command the attention of companies more so than game journalists can. That’s an issue.

It leads to this idea, though, of why aren’t more people getting paid to play games? I call this the leisure economy. If you think of what’s going to happen in the future, if we have self-driving cars, then we’re going to have a couple of hours free during the commute, when we’re driving. Half the time we spend in mobile phones now is spent playing games. Logically, the amount of time we’re going to spend playing games in the future is going to go up. If AI comes along and wipes out half the jobs that exist right now, including journalism, then what are we going to do? Do we have to work? Do we want to work? Why should we work if something else is going to do what we used to do? Maybe you can play instead.

Bing Gordon, one of the early employees at Electronic Arts, raised this point years ago. Why don’t companies actually pay gamers to play their games? What models can exist to make that happen? I think we’re pretty far along this road already, with all these kinds of people who make money playing games. Everybody used to envy being a game journalist because you got free games. But a lot more people can make a living in this kind of leisure economy in the future, I think. Our GamesBeat Summit 2018 conference in April will touch on this topic.

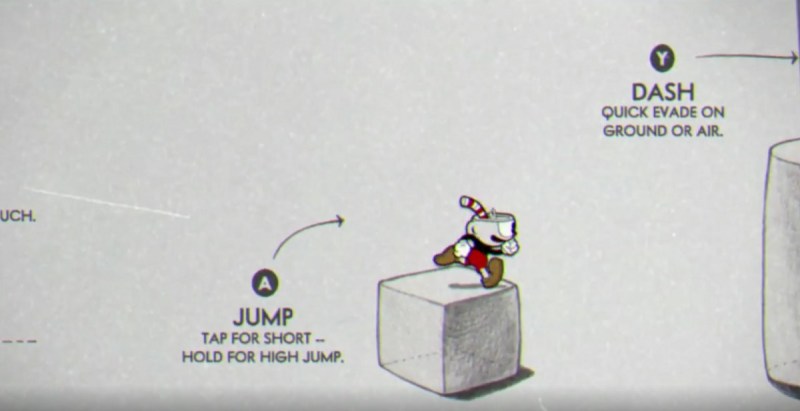

Above: I didn’t get far past this guy in Cuphead.

Well, I talked about having super fans, but I also have super haters. I’m that Cuphead guy, right? I posted a 26-minute video back in August from a demo I had at Gamescom in Germany. It was the first time I played Cuphead and the first time a lot of people were able to see what the actual gameplay was like. It was a very noticed video. But I did a terrible job playing it. I spent about two and a half minutes getting through a 30-second tutorial. I didn’t get through the entire first level when I played for the rest of those 24 minutes or so.

This went viral on the internet. It got 1.2 million video views on YouTube. That’s astounding for a VentureBeat video. [We usually don’t make videos, except for our GamesBeat Decides podcasts.] I’m okay with people attacking me for this. Saying, “You’re unqualified to be a game journalist, to review games.” I was fine with people seeing this video and concluding that. But I had a post to go with this that kind of said, “Hey, this is a joke. This is me making fun of myself. I’m self-deprecating here.” I do that a lot.

Above: Cuphead tutorial. It’s different in the final version.

But people didn’t see that post. They went straight into the video, and they went into the video thanks to a guy I would call a “shitlord.” On the internet, in this age of internet haters, we have shitlords who can direct our hate in their chosen directions. One person got ahold of my video, which had 10,000 views at the time or so, and by the time he had shared it and said, “This is why game journalists are unqualified to review games,” he helped me get so many more views from my video, because he cast it in a fake-news kind of way.

It’s very interesting to me how Gamergate and fake news share all this common heritage. When you think about Zoe Quinn and what they went after her for, these major transgressions of supposedly sleeping with journalists in order to get positive reviews were false. Then the Gamergaters said, “Well, okay, that didn’t really happen, but maybe it’s more like, well, using your friends to get positive coverage. Or maybe that’s not true? Well, these guys should have disclosed they were friends whenever they got coverage.” It turns out that the crime there would have been on the journalists themselves, not on Quinn. Disclosing things, yeah, it’s a good idea.

So I wasn’t very good at this game Cuphead. The nice thing was that other game journalists came to my defense. Influencers like PewDiePie created videos making fun of me, so it magnified that million views into many more millions of views. It was funny. It was taking an easy shot at somebody. But being on the receiving end of this, it made me understand what it’s like to walk in the shoes of a person who’s getting totally roasted on the internet.

We all make cruel and snide comments. We look at other people that we don’t like and we throw hate their way on the internet. It’s really easy to do that. It’s really easy to do that anonymously. But to walk in the shoes of these people who are getting so many negative comments — things like, “You should just go kill yourself.” You get a hundred of those a day, it kind of brings you down. You have to figure out, okay, who am I going to listen to here? When everybody in the world, it seems like, is telling you that what you’re doing is shit, are you still going to keep doing what you do?

We all make cruel and snide comments. We look at other people that we don’t like and we throw hate their way on the internet. It’s really easy to do that. It’s really easy to do that anonymously. But to walk in the shoes of these people who are getting so many negative comments — things like, “You should just go kill yourself.” You get a hundred of those a day, it kind of brings you down. You have to figure out, okay, who am I going to listen to here? When everybody in the world, it seems like, is telling you that what you’re doing is shit, are you still going to keep doing what you do?

It made me think about — okay, we need to be kinder to people. We need to go back to those ideas that I always like about journalism. Walk in the shoes of somebody else. Get a different point of view. Understand what it’s like to be someone. Have some kind of empathy. That’s what some of the best journalists do. They’re not personalities who are entertaining you. They’re good listeners, people who have empathy.

I got through this little difficult time for me. It really only lasted 10 days at the most before the internet’s attention went to somebody or something else. Having a sense of humor and some humility about it, telling people they should be kinder — sometimes they would respond and actually reciprocate.

Above: Dean Takahashi of GamesBeat wears the Atari Speakerhat.

But I do think gamers sometimes have legitimate gripes. When they have a good gripe, they make themselves heard these days through the internet. It turns out to be a good thing. Quite often, though, you can also see from the game developer’s point of view. Like, why would I want to make games for these people? I think they should ask these questions about outside in and inside out the same way journalists do. Do you want to make fun of people who aren’t skillful? Is it okay to drive newbies and the unskilled away from gaming?

I wonder if gamers will welcome a broader industry that will get them more and better games? That’s the best argument in the world for welcoming people into gaming. For welcoming diversity in games as well. Diversity among game developers. Why would you react in a negative way to things that are going to get you what you want? And so I don’t understand the resistance we’ve seen. I really hope that it’s temporary.

The latest rendition of this is the loot box argument people are having with Electronic Arts over Star Wars Battlefront II. They do forget, I think, that EA used to charge for downloadable content that came out after a game came out. Maybe three or four packs that they’d sell for $15 apiece. They decided that fragmented the community too much and they made those available for free. They’ve figured out a way, through loot boxes, to recover some of that lost money. I think I’m okay with that? But a lot of gamers are not. You wind up with gamers who feel like they’re being attacked, like they’re looked on by outsiders still. They don’t get the resources they deserve. They don’t welcome new people. I feel like this is something that’s not right about the industry still.

Above: Dean Takahashi tries out Star Wars: Jedi Challenges AR headset.

These are my goals as a game journalist. Seek out new perspectives. Create successful game events where we can make better games happen. Continue to write about the diversity of the industry. Chronicle the journey of people, games, and companies from cradle to grave. Gazillion died recently, and that’s a case in point, where I was covering them at the beginning and I covered them at the end.

I have written 15,000 stories at VentureBeat. I don’t think of them as stories so much as the people I met along the way. I always wrote more stories because I was writing stories about people who wouldn’t have stories written about them otherwise. People who were doing Kickstarters, things like that. I think Susan Cain’s Quiet book is one to admire. She asks this question in there, “How did we go from valuing character to valuing personality without realizing that we sacrificed something meaningful along the way?” Listening, I think, gets you a long way. You can find stories that no one else is telling.

If I have advice, it’s the Kurt Vonnegut quote, for people in the industry. “We are who we pretend to be, so we must be careful about who we pretend to be.”

Above: Dean Takahashi is a well-dressed warrior playing Skyrocket’s Recoil.

I would love to see game journalism thrive as both a business and a profession and an art. I hope everyone gets paid to play games just like I do. I wish we had as many sponsors as someone like PewDiePie. Keeping a distinction between journalism and entertainment matters. Realizing the difference between fake news and real news, that matters. Be kind, don’t be cruel. I think gamer culture should grow up. It should not stay stuck in time.

“Gamers are everywhere. Games find a way.” That’s a quote from Seamus Blackley, who was one of the creators of the original Xbox. He was inspired by Jurassic Park, that line about “Life finds a way.” Whatever obstacles are presented in front of it, life finds a way. Games make their way onto new platforms, even if they’re not intentionally created for games.

The term “gamer,” of course, has lost its meaning. Diversity matters, a diversity of sources and perspectives. This whole diversity cause plays perfectly and goes hand in hand with good journalism. I love creating a career that really didn’t exist before, and reinventing myself, especially by moving from newspapers to the web. You’ll all be called upon to do that during your careers. I waited a lifetime to get to games like The Last of Us, and I do wish that my brother was around to play it with me.