Amazon clearly has ambitions in the high end of the game business. Today, it announced that Command & Conquer veteran Louis Castle has become the head of Amazon Game Studios in Seattle. It has also hired high-profile developers such as John Smedley, Rich Hilleman, and others as well.

And the company is using its Twitch gameplay livestreaming division and its Amazon Web Services as the foundation of its relationships with game companies. It has also recruited high-profile developers such as Leslie Benzies and Chris Roberts to use its Lumberyard game engine, which was initially licensed from Crytek and is now Amazon’s own technology. Getting those developers to use Amazon’s game technology gives the company cred with gamers and the game industry.

As vice president of games at Amazon, Mike Frazzini is responsible for a lot of this push. I caught up with Frazzini at the Game Developers Conference last week in San Francisco. He said he has been playing a lot of Polytopia, a turn-based strategy game, on planes lately.

Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation.

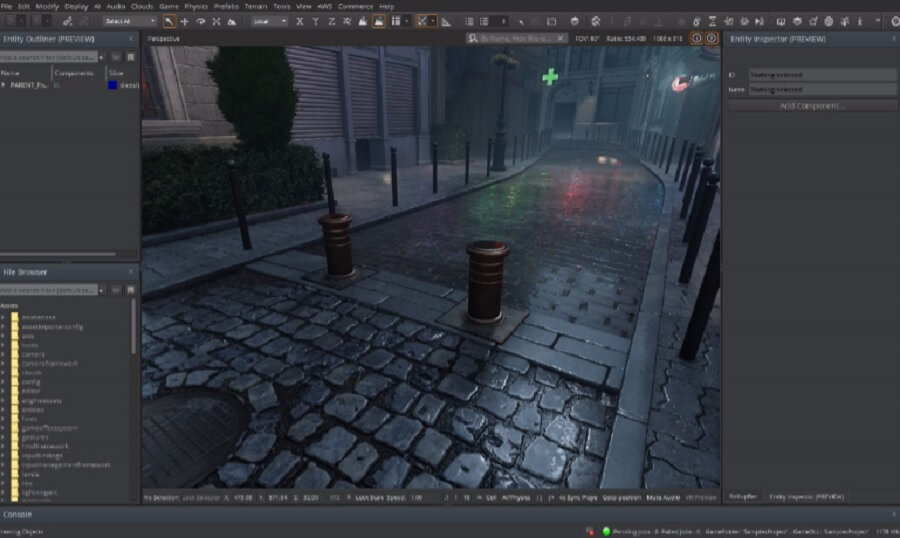

Above: Game art created with Amazon Lumberyard game engine.

GamesBeat: How’s the game engine environment looking right now?

Frazzini: It’s looking great. We’re just over a year since we launched into beta and we’re exceeding our expectations in terms of customer adoption and customer feedback. Game engines are hard. We know that. We’re feeling good about our progress. This is our biggest GDC as Amazon – bigger booth, more sessions, more classrooms, more products to talk about. Between Twitch and AWS and Lumberyard and Twitch Prime and our games, there’s a lot of cool stuff going on.

GamesBeat: You have some high-profile game developers switching over to Amazon. Is that a deliberate sort of targeting strategy you have?

Frazzini: If we think about our strategy, it’s to focus on customers. We look for frontiers to be inventive. We see two fascinating frontiers in games. One is the cloud and the other is communities. If you look at the number of ways gamers participate in communities now, it’s more than it was in the past, and the amount of people participating is more than in the past, and the amount of time spent is more than in the past. That’s how we think about cloud and communities.

If you notice, the games that signed up are very interested in integrating with the cloud. They’re very interested in building large online communities. Chris Roberts, when we sat with him, he said, “I really want a Twitch feature that allows people to join a broadcaster from the chat.” I said, “We built something called join-in. We’re about to release it.” He talked about the cloud and said, “Well, I really need this and this.” “Actually, we’re working on that right now.” We’re aligned in this notion that the cloud is important to deliver great game experiences.

I had dinner with John Schappert last night. We were just chatting about the industry. He said, “I just built this game, and I had to spend half my team on engineers to build the online tech.” I said, “John, this is exactly what we’re doing. We’re making that easier and easier.” When we talk to customers, we hear huge numbers of opportunities that we can pursue. We’re just getting started. This is very much day one for us.

Above: Amazon booth at GDC 2017.

GamesBeat: It seems like it helps to have names like John Smedley or Chris Roberts recruiting. Or Leslie Benzies, that was a good one.

Frazzini: I just love what they’re doing. I’m so excited. It’s a good fit. And a similar story. They want to do this ambitious game and our technology is very well-suited for it.

GamesBeat: Are you seeding these people with funding?

Frazzini: We don’t talk about that. But I would say—they’re customers because they like the product and they like where we’re going.

Above: Amazon Lumberyard

GamesBeat: It seems to me that the state of the whole game industry, if you look at how treacherous it can be—it seems like the industry needs platform owners of all kinds to step up. Facebook has gone out and said, “We’ll spend $250 million again on Oculus content.” Intel seems aggressive. From what I sense, Amazon seems that way too. It’s a time when venture capitalists are receding. The opportunities to do something ambitious with capital don’t seem as plentiful anymore, unless you’re Magic Leap.

Frazzini: You can certainly turn to Amazon and Twitch and say—we’re investing heavily. We’re very excited about the business. The amount of we’ve done in the last year is significantly more than in the year before. We’re just getting started.

When you talk to game developers, what do they tell you? It’s hard to get discovered. Very common. Probably the most common request. The other thing is, like with Schappert, they don’t have the engineers to build a lot of these systems they need. We can help with both of those. The third thing they say is they need to make money, obviously. It’s a business. We think a lot about how we can help developers make money.

Here’s an interesting connect-the-dots. We don’t think we’re in the game engine business. We just think “customers.” We’re in the business of helping developers succeed. We have three customers in games: developers, broadcasters, and gamers. When we think about game developers, they make money from selling content. It’s increasingly digital content. They make some money on ads as well. But they’re not selling a lot of physical merchandise, even though they have some of the best IP on the planet. How can we help them sell physical merchandise?

In September 2015 we launched a program called Merch by Amazon. If you’re a content creator, you design a T-shirt. We make the T-shirt available in all the sizes and colors. We do all the manufacturing, logistics, customer service, returns, payments. We just send developers checks. That business is doing exceptionally well. Developers have told us, “I can sit here in the middle of the night, set this thing up, and when someone goes to Amazon and searches for my game, the shirts pop up underneath.”

What does that have to do with anything? It has to do with listening to the customer. When you do that, they tell you about these problem sets, and then we think about how to solve them. In the early days a game engine was a renderer. It made graphics. Then people added physics and animation and all these other elements of what a game engine could be. Today you have this sort of definition. I look at that definition and I think it’s wildly incomplete. When you talk to a game company, they need to reach customers. They need to make money. They need to connect their games to the cloud more easily. We see a tremendous amount of opportunity to be inventive.

Where we sit, talking about the platforms—Twitch is on Xbox. AWS works just fine on a mobile phone. Lumberyard is cross-platform. Between Twitch Prime, Twitch, Amazon’s retail business, we look for how to help developers succeed. That’s the inspiration. We’re not going to solve all the problems, of course, but we think we have a chance to solve a good bit of them. Feedback so far has been very positive.

Above: Star Citizen’s combat in action.

GamesBeat: One interesting thing to me is that social discovery is a way to stand out and deal with how there’s millions of other games on the app stores. Social can disrupt the app stores. As long as the app stores are charging their 30 percent, they’re vulnerable in some ways. Do you have any feeling on that, given that you have both social in Twitch and an app store?

Frazzini: I’ll focus more on the community and social part. Discovery is hard. I don’t think there’s ever going to be one way of discovery. There are too few today. Games that embrace the notion of online communities, guess what? They get discovered by more people. People talk about them more. When you talk to Smedley about how he thought about H1Z1, he thought very heavily about Twitch.

There was this saying in boxed product game development, where you design your game for the marketing vehicle. Okay, let’s apply that to today. What’s the marketing vehicle? YouTube is a marketing vehicle. Twitch broadcasters, user-generated content, these are all forms of marketing where you’re helping people create and share content and participate in communities.

Another way to look at it, the Twitch community has already changed the way games are experienced. We think what’s next is for the Twitch community to change the way games are made. This is the idea that you build your game for the audience. Don’t just make a game that’s fun to play, though that’s already hard enough. If you also add elements that are fun to watch, that helps you with discovery.

Above: Matthew Smith, Colin Entwistle, and Leslie Benzies are making Everywhere.

GamesBeat: It can also change how games are sold.

Frazzini: Exactly. That’s a big part of it. With Twitch, hey, you’re here watching. Maybe you want to buy it too. If you can bring the broadcaster into that equation, that’s another important customer for us. How do we help broadcasters make more money? One way is to sell games on Twitch and give them a cut. That works out pretty well.

GamesBeat: Do the app stores still have an important role as the foundation of all this?

Frazzini: Absolutely. I don’t want to speculate on other people’s businesses, but I think they’ll always be there. You already see it with Facebook and different forms of user acquisition that happen in and around games. The reality is that game developers are saying, “Where are gamers that might like my game? How do I engage with them?” Sometimes it costs money to advertise. Sometimes it’s through a social engagement or something like that. But there’s a shortage of those opportunities for game companies.

Walk around and ask 10 game developers about their number one problem. I wouldn’t be surprised if all 10 said “discovery.” At least eight would. I doubt it’d be three. So how do we help? I don’t think a single thing will ever be the only form of discovery. It’ll always be a collection of different ways.

GamesBeat: 1App.com made me think about this. They have virtualized Android in the cloud, so you can serve games directly to people. Kim Kardashian puts in a link for your game, you click on that, and you start playing instantly without going to the app store. Thirty percent doesn’t go to the app store. There might be a retention problem, because how do you go back to that game? But that business description made me think that there are interesting ways that things could still change.

Frazzini: When you talk to developers, a problem that’s not on their list is paying 30 percent to the app stores. That’s just what it is. People understand that when you’re helping with discovery, that’s part of the marketing and advertising for your game, making it accessible. Discovery is more challenging than the economics associated with the app store relationships.