Above: Rock Band.

Takahashi: But these super fans….

Kim: Those aren’t super fans. Those are haters. Don’t get confused.

Takahashi: I wonder if you have two sides to something here: super fans and super haters. I remember somebody telling me that Sony’s product lead for the PlayStation in one country got death threats because Sony had to raise the price for the machine there. Those people cared enough about the PlayStation 4 that they would make death threats to someone who did something slightly negative. That’s a weird world we live in.

Kim: That’s so much the gamer world. We talked about Ultima Online earlier, perfect example. In Ultima Online, we had super fans and super haters. The super haters were hacking our gold system, exploiting cheats. They were trying to take down our servers. They were posing as newbies, befriending other newbies, and then killing them to take their loot. They did all these things that made it tough for us.

The super fans were the people reporting them, the people saying, “Hey, you want to conscript us into a virtual army, and we’ll go get them?” They are two sides of the same coin, but again, I want to give you guys something valuable as developers from this. Don’t be confused between your super haters and your super fans.

The super haters can sometimes be swayed. For example, in Ultima Online, some of our best security experts came from the hacker community. Classic. Not all of our hackers could be dissuaded, but sometimes, when we found somebody exploiting something, instead of going nuclear we would say, “Would you like a job interview?” It worked really well.

But here’s the thing. You and I don’t agree on this, but this is my advice to you. You have a lot of super fans. Your super fans are the people that love what you’re doing, that found it valuable that you were transparent, that jumped to your defense. Many people jumped to your defense, myself included. Your super fans are into what you’re doing, and they want you to succeed, and they can be, in a sense, your co-creators.

Your super haters want you to be doing something different than what you’re doing. It’s very hard, as a developer, as a creative person, to say, “I’ll listen to this person’s feedback and not that person.” I’m here to tell you, as someone who’s worked on five breakthrough worldwide hits, and then dozens that weren’t — a thing all those hits [had] in common is that they all had haters first of all. But we didn’t get freaked out by them and focus on them. We managed them, but we really focused on the people that we were serving. It was one of the hardest and one of the most important things in breaking through to a bigger level.

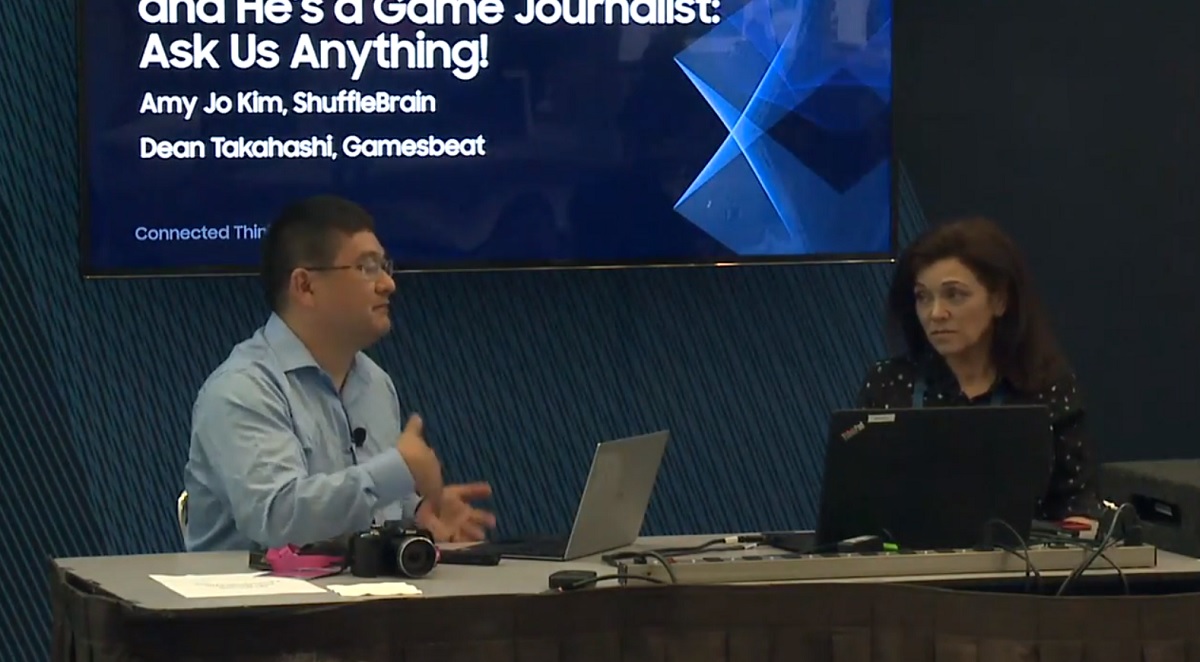

Above: Dean Takahashi and Amy Jo Kim.

I’m not saying we ignored them completely. I’ll give you a good example. Ultima Online, for those of you who don’t know, was like a precursor to World of Warcraft. When we launched it, we had done beta testing with all these super fans, people that loved it, people that loved Richard Garriott’s previous RPG games and their very interesting moral universe, blah blah blah. We had all these people that had gone to [Renaissance fairs], people who would role play. “Oh, milady, thou lookst beautiful this evening.” Stuff like that. We called them the “men in tights.”

Then, we launched the game, and this was right around when Doom and Quake were big, with this reputation system we had tested with our super fans. Guess who came into the game? All the Doom and Quake people, 13 years old pretending to be older. The rule in Doom and Quake is shoot anything that moves. They came in wearing those same goggles to our beautiful thee-and-thou men-in-tights world. Boom. Big time problems. Maybe some of you were there.

What did we do? Did we kick out those people? No. But they were asking us for things. “You should do this. You should build this feature. You should add more blood.” That’s what they were asking for. We didn’t give it to them, though, because those weren’t the people we wanted to please.

That’s my message to you. I think it’s the same thing with these, my word, idiots who want to tell Dean that simply posting, “Hey, this was hard for me, this really weird arcane game” — people who think that makes him not a real game journalist, I believe, are living in the past. They wish they were living in a present where people like them were the majority. They’re not, and they’re pissed.

Above: Zoe Quinn’s book Crash Override chronicles her Gamergate experience and how she is fighting back.

Question: What do you think about the trend toward more and more vocal negativity around games on the internet and social networks? We saw, a couple of years ago, women receiving death threats over their comments about women in games.

Takahashi: It’s been encapsulated by this phrase, “Gamergate.” That’s been going on for a couple of years and been fairly relentless in the games industry.

Kim: It’s a cyclic thing. I agree that it is a trend, but it’s not new, any more than VR is new. It cycles back and forth. What’s happened with Gamergate is it got a name. It got a meme. Let’s talk about Milo, Dean — Milo and Gamergate. How many of you know about Milo Yiannopoulos? There’s a very weird, interesting confluence between Milo and Gamergate and these trends.

Takahashi: Milo was an unknown journalist at Breitbart for a while. He wrote a story about a conspiracy among game journalists who would talk to each other and try to influence review scores or talk about problem people in the industry or show their biases against other people. I was part of this network of game journalists. It was a network of game journalists talking about freelance assignments and things like that.

Somebody gave Milo copies of the history of this networking group and he pulled out stuff that had to do with Gamergate and Zoe Quinn and all that. There were some very unguarded comments that journalists made about that, and so, he wrote a story as a big expose of this conspiracy. Which, having been on the inside of it, I didn’t think was much of a conspiracy.

He became more famous because of that, and you can tell from the Buzzfeed story that ran just a week or so ago that went into all of Milo’s emails — he parlayed this into helping create the alt-right and doing their best to get Donald Trump elected president. It’s an interesting connection between — it’s Milo and Gamergate, Milo and the alt-right, Milo and Donald Trump. Steve Bannon, Breitbart’s chairman, was Donald Trump’s chief strategist.

Kim: My hope is that this trend is the death cry of nasty old racists, who see that they’re a dying breed, and that women and minorities and people of color are the future. Who cares if you’re a man or a woman or what color you are? Can you make a game? Can you write code? Can you make art? This trend, and it is a trend, is rising concurrently with power shifting in the gaming world and in the political world away from these men, and they’re grabbing it back.

Takahashi: You see it as a death knell, then?

Kim: I see it as a death knell. That’s my hopeful vision.

Question: Aside from the conflict between super haters and super fans, what do you think about this question of what kind of gamer should a game journalist be? A game like Cuphead is hard because it was made to be hard. Shouldn’t a journalist covering that kind of game be the more hardcore kind of gamer, someone who plays that kind of game?

Takahashi: The phrase “game journalist” just isn’t very precise. I haven’t been, say, reviewing games day in and day out for 20 years. I’ve been writing business stories and technology stories about games. I’ve been going to preview events and playing games at some of them, but my pattern is to play something for a few days and move on. There are games that I get into and I play and I review, but that’s less frequent. I just did Middle-Earth: Shadow of War for about 60 hours and finished it.

We have other people who tend to be the experts in particular areas. We had one of those guys, Mike Minotti, finish Cuphead and then write the review. That’s the way it should be. If you’re doing a formal review and giving it a score, definitely, you want someone who’s skillful enough to see the whole game to review it. There’s no question about that. We abide by that.

I was making a self-deprecating video as a preview of Cuphead, right? We didn’t apply that same rigor to whether I should do that or not. There’s always some value in showing people what a game is like before it comes out. In fact, if you look at game marketing campaigns, they’ve stretched out for years now. Assassin’s Creed: Origins will probably have a dozen trailers go up before the game ships on October 27. It’s part of the landscape. But there is a very big difference in being able to just play a game in a preview and finish the whole thing.

Some games are more difficult. We review a lot fewer MMOs than we do single-player campaigns. In that case, we would say, “We played this MMO for 30 hours. Here’s what the experience was like.” We wouldn’t necessarily give it a score. We’d give our opinion of it, whether we think it’s worth your time or not, but the score element is very hard to give to MMOs. I imagine that you ran into this in creating MMOs as well.