Above: Star Wars characters at the ETC.

You can see out the window, and across the river, it was a huge steel mill. On this side they smelted all the steel. The boats would come up the river and drop off coal to heat the furnaces, and they’d ship it over on the “hot metal bridge” to the other side, where the boats were picking up steel. They’d shape it over there and take it out into the world. That’s how big a logistical design it was. Then, when that all went kaput, with a lot of funding they turned all this into a research park. Pitt has a building down here. Switch and Signal. Across the way it’s retail and restaurants. Forty years ago Pittsburgh was Detroit. I wasn’t here, but they recovered. It just took a while.

We have a lot of people who’ve gone on to Pixar. A lot of kids want pictures with this. He’s just Styrofoam, and one time this kid touched it. Spiders had laid eggs, so the kid touches it and all these spiders fall out of the. They all screamed and I thought, “Oh, that’s so perfect.”

The mix we have in the student body, we have to mirror that in the faculty. We have faculty from technical backgrounds, artistic backgrounds, design, industry. Most of the faculty are here. Here are current projects, and what our alums are up to.

Building Virtual Worlds, this is from that class I was telling you about. A team of five made two of these in two weeks. You put them on the floor and two players stand on one. You cooperatively compete against each other. Part of what’s fun about Building Virtual Worlds is we get them out of their comfort zone. They’re not allowed to use standard input-output devices. They have to use the weird stuff we have around or make their own.

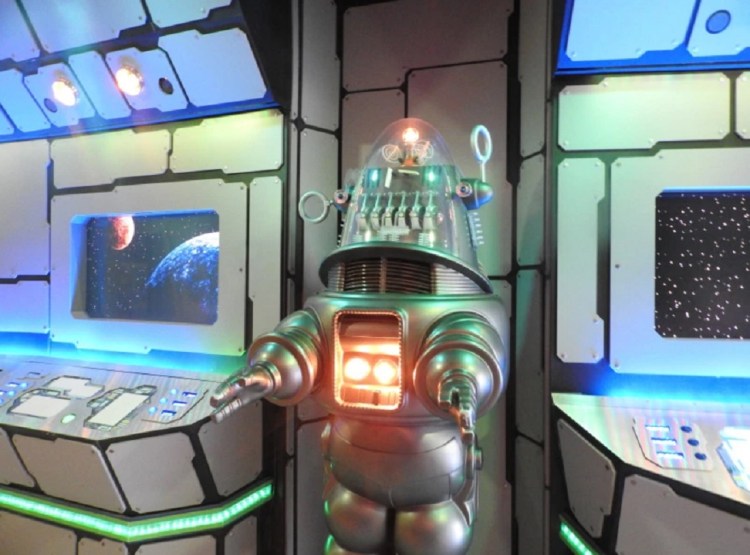

Anthony Daniels is on our faculty. He’s a visiting scholar, along with Michael Keaton, who’s a native. Anthony came because of the Robot Hall of Fame. He was an MC for the Robot Hall of Fame, a joint initiative between CMU and the Science Center. It has two branches: entertainment robots and industrial robots. The idea being that entertainment robots inspire industrial development. He came to CMU one year and Don talked him into visiting. He’s an amazing critic. He can articulate why what you’re making doesn’t work for him.

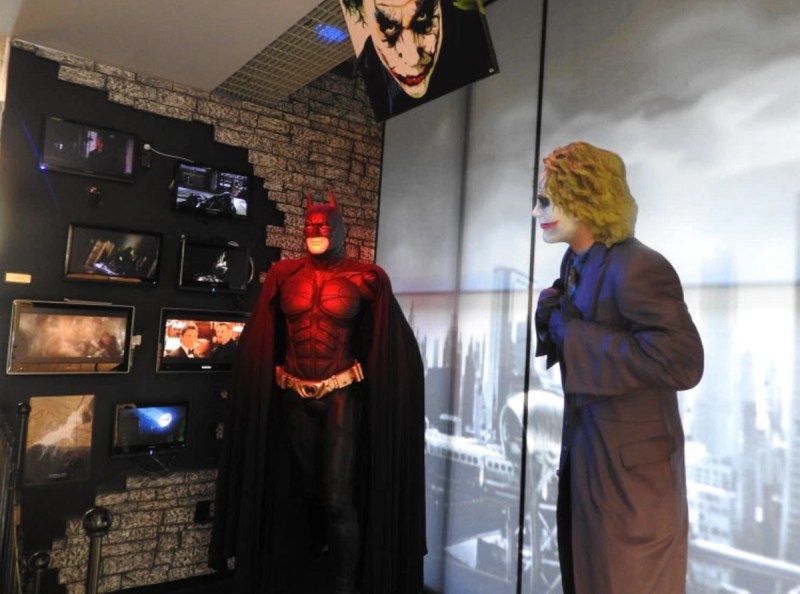

Above: Batman and the Joker at the Entertainment Technology Center.

GamesBeat: Our GamesBeat conference last year was a bit like that, about the meeting between science fiction, games, and tech.

Davidson: I love stuff like that, where it gets a little interstitial? That’s where some of the best, most interesting stuff happens.

Up here, if you see colors, it’s us. If it’s white—you’re going to start seeing hazmat showers. Our colleagues are biomedical, so they do a lot of work with materials where, if the alarms go off, you get out of the building now. Here’s a project room, where they sit together for a semester. A lot of the project teams are over here.

You might find this interesting. We have an experimental publishing imprint called ETC Press. We started it about 10 years ago now. At the time there wasn’t really a good academic forum to talk about games. Nobody was publishing in the field. With the support of the provost and the president, we said, “We want it to be open access. We want to have this connection between industry and interdisciplinary work.” Brad King — he worked at Wired – his background is in the industry as a writer and editor, and then he got into academics. We hired him on as a full-time editor to evolve ETC Press beyond a small experimental thing and really represent CMU.

Have you heard of Give Kids the World? It’s a non-profit theme park in Florida affiliated with Make-a-Wish. A lot of kids who want to go to Disney World through Make-a-Wish, they stay there, because it has facilities to handle kids with disabilities. But some of them are so sick they can’t go to Disney, so they have a theme park at Give Kids the World that’s held together with donations, duct tape, and a lot of love. Mickey visits every day. Bugs comes from Universal.

We’ve partnered with them so once every year or so, we go down there and refresh their exhibits. It gives our students great design challenges. A big thing we’re trying to do, not to be too cliché, but how can we use all this to make the world better? We talk about the creative good. I want to make sure you meet Eric Brown. He and Asi Burak were the founders behind PeaceMaker and Impact Games.

Asi’s now doing Power Play in New York, and Eric is now our director of Alice, the brain research project. It’s still going, the little blocks of text teaching kids how to program. Ever since Randy passed away it’s lost market awareness to Scratch, but it still has millions of people around the world using it. We’re trying to decide—do we just open source it? Try to revitalize it? Depending on where we are now. But there’s so much happening now. Back when Alice started it was pretty much just Alice and Scratch.

If you’re not familiar, Alice is Randy’s old research project to teach kids how to program through storytelling and animation. It’s these blocks of text. You pull everything through the screen and below it it’s showing you the code that makes it happen. Eventually you can go down there and write the code and see how it works.

Above: Eric Brown is working on Alice, Randy Pausch’s project to make programming more accessible.

Eric Brown: The super fast elevator is that it was Randy Pausch’s. It was for VR prototyping, for non-technical people. It then moved on to being an early CSA tool at the same time as E-Toys and all of the block-based coding revolution. It’s been around since the late ‘90s — first as a “how to prototype VR” thing, then “how to author 3D worlds,” because that was also fresh and new. It’s continued on since. Now there’s a push to get us back to publishing for VR, because VR didn’t take off in the late ‘90s, but it’s making another attempt now. It’s at least more accessible. Transitioning from block-based to Java is one of the focuses, and object-oriented and things like that. It has that same space as Scratch or Snap or any of the other block-based ones, except for we’re in 3D, which kids respond to more in my opinion. Then we can layer tools for transitioning from block to text, which is one of the challenges. We’re making more and more of these early ed tools, but we’re not doing a great job of transitioning from what they learn there to other languages.

Davidson: One thing that Alice has always done really well is it’s always had a curriculum. It’s not just saying, “It’s fun! It’s out of school!” We develop lesson plans for using it. The community has returned that. It’s had such a storytelling component from its inception that it’s been very appealing and successful with young women and minorities. Some of the biggest successes that keep us going, everything is being used in the developing world. Stateside it’s all about Scratch, but in the rest of the world a lot of people have been using Alice because of the curriculum support, because of the storytelling.

Brown: Little things that have helped with that—Oracle is one of our big funders. They do Oracle Academy globally and use Alice a lot in that. Some of that is the ability for us to localize. What’s a detriment to us in some circles is we’re not web-based, but in places in developing countries where internet access isn’t as prevalent, the fact that we’re a desktop application helps us.

Davidson: We’re trying to give it a push, see what happens.

Brown: We’re sort of rebranding. We’re doing some stuff to wrap it back in Unity, to try and get it to VR and those types of things. We’re trying to get to Daydream and doing other research into how VR can be used to visualize and learn CS concepts. We want to do game competition stuff, because of my background with Impact Games. We’ve done a couple of competitions. One was in Romania, where they were sending me to judge stuff. A bunch of worlds were created that had a sort of anti-bullying context. We want to run some competitions using Alice for social issues stuff as well.

Above: A Mac sits atop an SGI Indigo workstation.

Davidson: Here’s a fun one, an SGI. Once upon a time they were so expensive.

GamesBeat: $20,000 or something?

Davidson: Now it’s just holding up an old Mac Plus. This is all stuff from Randy’s collection, the old virtual reality stuff from way back in the ‘80s and ‘90s. The first push of VR, when it wasn’t that great. We have an audio studio here, a green room with a visual suite. Wood shop over here, metal shop over there, a painting room with a fume hood. We have a full set of CNC routers and laser cutters. One past project, they had this idea of creating robotic puppets. So it’s not really a robot.

GamesBeat: Is that Jeff Katzenberg I saw in the video there?

Davidson: Yeah. He’s very charming. He was the man behind the curtain. There’s a pinhole camera in the nose, a wide-angle camera on the stand, and he interacts with the kids. He was like, “Can we get a robot to talk to kids about science in schools, get them interested in STEM?” The puppet’s gotten to a point where we don’t really ship him around anymore. It’s about 10 years old now. It breaks. But it’s amazing how much kids react. They gave him a birthday. But the whole story is developing a way of interacting with kids.