testsetset

Carnegie Mellon University’s Entertainment Technology Center became famous in part because of The Last Lecture.

Computer scientist Randy Pausch and Donald Marinelli, a professor of drama, started the graduate school that combines entertainment, technology, and video games in 1999. Pausch contracted cancer, and he died in 2008. But before he did, the beloved teacher gave a final lecture about achieving your childhood dreams. It was so moving that it was turned into a book and chronicled by Diane Sawyer in an ABC Special. The YouTube video capturing Pausch’s inspirational message about life lessons has 18.6 million views.

Pausch’s memory is still very much alive at the ETC. The Last Lecture and the creativity it encouraged inspires Drew Davidson, the director of the ETC, which is now considered one of the best schools for video games, tech, and entertainment in the country. The place is a graduate school with about 160 students at any given time, and it sits in a building on the banks of Pittsburgh’s Monongahela river. In the middle of a 48-acre research park that was once a gigantic steel mill, the ETC is a source of Pittsburgh’s economic transformation.

It is where the old economy meets the new. You would never know that this was once the Rust Belt. And it shows that you can create game ecosystems pretty much anywhere in the world. The ETC has become a place where people build their dreams, and it’s a nice fit for our new VentureBeat channel Heartland Tech and our upcoming Blueprint conference in Reno, Nevada, on September 11-13.

I visited the place recently and talked with Davidson while my daughter and I toured the halls. I took pictures of the zany environment, which is festooned with Mario imagery in its bathrooms and has huge Batman figures in the halls. If you want to get inspired to be creative, this is the place to be.

“It’s like an MBA for people in the creative industries,” Davidson said. “It shows them creative career path opportunities. We joke that everybody here is like a mutt, trained in a lot of different things.”

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Above: Drew Davidson is director of the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University.

GamesBeat: Tell me about this place.

Drew Davidson: This is a great example of a past ETC project that’s grown. The ETC is very project-oriented. It’s going on 18-20 years old now. It was founded by Randy Pausch, out of computer science, and Don Marinelli, out of drama and the college of fine arts. Randy Pausch’s last lecture, I’m not sure if you’ve heard it, but if you haven’t you should watch it. It’s amazing.

Their idea at the time was inspired by Randy doing a sabbatical at Disney Imagineering. Imagineering was just throwing people from different disciplines together and making amazing things. He came back and pitched the idea – we should do a program like that. It’s a graduate program primarily, because that gives us people who have at least an undergraduate program. We do get people who have industry experience as well. We can pull in specifically from different disciplines.

We try to actively recruit about 40 percent from a technical background, whether they’re programmers or engineers, 40 percent from artistic backgrounds – 3D, 2D, visual effects — and then in the middle from all over. Creative writing, theater, drama, music, business. We’ve had biology majors. They all get thrown together and they’re going to do things together.

Don and Randy went around the country visiting places like Pixar and Electronic Arts and Universal and Disney looking for input. They wanted to craft a program that trains the next generation. The best way I can describe it, it’s like an MBA, but focused on the creative industries, as opposed to finance and business. You design and develop.

And so we take all these people together and they work on teams making things like this. It’s not just games. We’re interested in entertainment technology across the board. We have lots of video games, but also things like themed entertainment, location-based installations, mobile, virtual reality, augmented reality, short film and animation, you name it. The mix is really interesting to us.

That breadth is also where we’re curious in terms of fields. How do you use all of this, not just for entertainment, but also for education and learning, maybe medical and health? Pittsburgh has the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, and we’ve done a lot of collaboration with them, how to use technology for health and medical. Business and training, of course. Civic engagement. Social impact issues. We’re very interested in exploring that range.

What’s fun for us and students—the universal is that you’re working with people, and people can suck. Your team can drive you crazy. The client can drive you crazy. Your boss can drive you crazy. If you do anything on the internet, look out. But that’s the universal. You’re always working with people and you have to figure that out. How do you collaborate and do creative problem-solving together in a conductive manner?

The thing that changes, which is exciting—five years from now, what’s going to happen? Ten years from now? Thirty years from now? They’re projecting that people her age are going to have 50- or 60-year careers, thanks to lifespan and cost of living. Five years ago, who would have guessed that VR was really coming back, and now it is. In 10 years, what’s next? Getting really comfortable doing something that’s never been done before, taking in lifelong learning and becoming comfortable with that, that’s something we try to focus on around here. Your kind of “I can figure it out” skills, as opposed to, “I just want to do the same job for 30 years.”

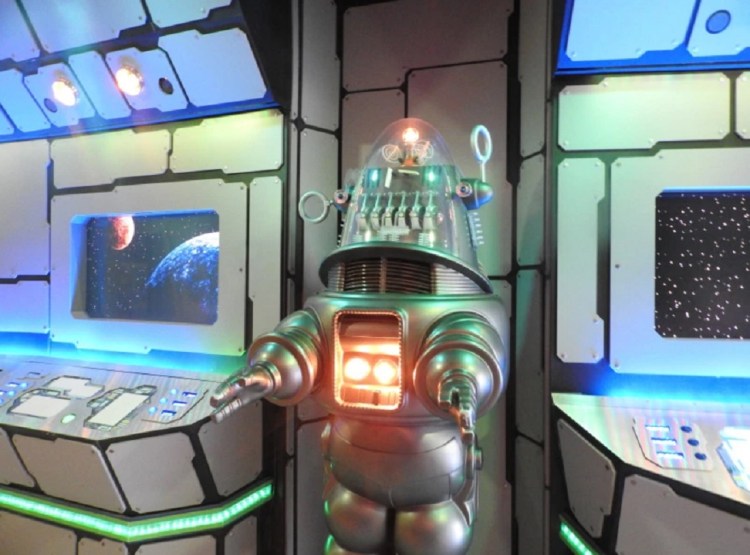

A group of students will be challenged by the ETC. Our projects can run in a variety of fashions. “Theme this hallway, so when you step off the elevator it doesn’t just feel empty.” When they originally started, both sides of the hallway were kind of like that. Then we did another semester where they had theming on both sides, but they had some fake panels. We do lots of tours here, particularly because of Randy’s Last Lecture. We get lots of kids in the building and they’ll touch anything. We thought we should put something up here to make it interactive. They started hanging screens and doing things with touch pads. It evolved into this behemoth. We’re only a two-year degree, so our students graduate and leave us, but the staff keeps this going.

GamesBeat: How many years has this robot thing been a work in progress?

Davidson: Six or seven? It stagnates sometimes. Students have to want to work on projects. We don’t force them to work on projects. This summer we’re working with some students and staff, our technical staff overseeing it, to think about ways to use all the screens. There are RFID readers here, things like that. When we originally did it there was no professional platform that could support six screens with six different inputs. We used Panda, an open source platform that we used to support with Disney. That allowed us to crack open the engine and make it work. When Unity came out Disney said, “Oh, we’ll put support in Panda [programming environment] and just use this Unity thing.” It took until just this year, believe it or not, but Unity can support this. We’re porting it to Unity.

GamesBeat: Jesse [Schell, CEO of Schell Games] talked about switching from Panda.

Davidson: Right. We’re sort of tech-agnostic. We want our students to understand how to problem-solve regardless of the tools. A big part of it is, we take that mix of students I was telling you about, and we put them through what we jokingly call boot camp. It’s a set of core classes they take together.

One is Building Virtual Worlds, that Randy Pausch taught. Now Jesse teaches it with Dave Culyba. It’s a rapid prototyping class. Team of five, two weeks, make something go. Shuffle, new teams, two weeks, go. Crazy crunchy timeline. There’s a lot of tech involved, but really, the meat of that class is problem-solving with people you don’t know well. You have to figure that out. Two weeks later, do it all over again. He talks about those head fakes. The head fake is, “Oh, it’s tech.” It’s not really tech. It’s people and problem-solving.

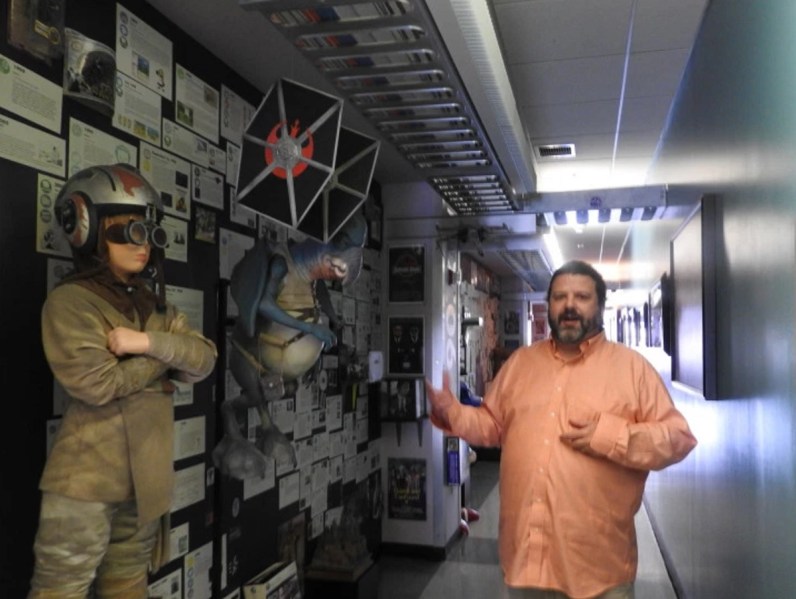

Above: Drew Davidson walks the halls of the Entertainment Technology Center.

At the same time they take a class called Visual Storytelling. That’s also a team-based class, kind of using the language of cinema. How do visuals and audio make something more immersive and engaging? But they’re in teams all semester long, working on three-week engagement making little short films to try to tell stories. We feel stories are an important part of any experience. There’s an intentional tension between those two classes. You’re switching all the time. And you know how group work is. “I love my team!” Nah, not so much. But you have to figure it out.

The other two classes—I teach a fun one. “This is a professional program. We want you to be able to talk about what you’re doing and why.” Understand design and development. Give them a sense of the creative industries and career path opportunities. Then the last class they take is everyone goes through improvisational acting. They have to take it together. It’s not about being funny or becoming better actors, but thinking about sharing – sharing credit, sharing ideas.

It’s a great brainstorming paradigm. Any time you think about interactive, we think performance is a better metaphor than cinema. Performance and theater is great way to think about it. It’s visceral. When things aren’t going well with improv on stage—we work really hard to have that translate into your creative brainstorming on a team. Are you doing that well together?

GamesBeat: How many people are here at any given time?

Davidson: We try to take about 80 students every year, and it’s a two-year program, so about 160. We do have a location out west, in Silicon Valley. We’re housed at Electronic Arts in Redwood Shores. The director out there is Carl Rosendahl. And I love this little cognitive dissonance: the other faculty member out there is Erin Hoffman. The EA_Spouse is now working for us at EA. They can take about 20 students a semester. It’s an opportunity, not an obligation. So we roughly have 140 students out here and 20 there, plus some co-ops and things like that.

Percentage-wise, we probably have 50 percent women to men. Because the breadth of our interest, it’s really attractive. It’s maybe 60 percent international now, with the bulk being from mainland China and Korea. About 60 percent come straight from undergrad.

GamesBeat: I thought it was interesting that Jesse was a stand-up comedian.

Davidson: Right. A street performer, a circus guy. Brenda, the faculty performer who teaches improv, was in an improv troupe that did it out in the streets. She did ren faires and stuff like that. There’s a weird—everyone here, we joke that we’re a mutt. Everyone brings a little bit of something.

GamesBeat: I found that the high-ranking schools in video games always have this mix of disciplines. USC has that collaboration between different departments.

Davidson: That’s what helps you excel. What made sense down here—after that first semester, they get through that and it prepares them for a semester on projects. They do stuff like this hallway, or they work with client-sponsored stuff, or grants, or research, or they can pitch their own ideas. We have a greenlight process, very similar to the industry.

Everyone here has worked in the industry. That’s a big feature of the program. We wanted that balance for a professional program. I worked in Austin back in the day, and now I consult a lot. It’s fun being at a school. You get a good sense of the pulse of what’s going on, because everyone talks to you. When I was in the industry, they wouldn’t even let me in the door. I was the competition.

GamesBeat: It seems like you guys encourage collaboration with industry. Jesse has this dual role.

Davidson: Right, exactly. Everybody is still actively involved. Jesse has his company. A lot of us consult. A lot of us are on boards or even more directly involved in some things. Everyone keeps a toe in the water. There’s a balance. Some of them are like, “Historically I’ve been in academics, but I’ve spun off companies.” Jesse has mostly been in the industry, but he teaches here. It’s a way to stay relevant, keep the street cred as it were.

Another thing that’s important to us—we hired Heather Kelley as one of our recent game designers. She had this mix. Jesse has a certain skill area. Chris Klug is another game designer here who comes from a focus on story. Heather is coming from art, aesthetics, indie, almost a punk sort of experience.

So the students come in and through two-three semesters they work on projects. They can do industry co-ops if they want. Then, on the back end, more than half go into games, because that’s where everyone is really passionate. We’re heavily recruited. I think 95 percent of our students get jobs within six months of graduating.

I remember one student who was an amazing 2D artist. He was getting offers to be a concept artist at companies, which is pretty rare. But his dad was like, “3D is better than 2D,” and he didn’t have a 3D portfolio at all. He could do gorgeous 3D art, but it took him a week, whereas someone with more of a proclivity would do it in a day. I said, “Come on, just start somewhere as a concept artist! That’s an amazing job!”

Above: A collection of old video game systems at the ETC.

GamesBeat: How do people figure out where they want to go deep in the program?

Davidson: A couple of things will happen. Sometimes students come in with a pre-conceived notion. Sometimes they come in wanting to take a left turn. “I don’t want to become a programmer. I want to become an artist, so I’ll come to the ETC to become an artist.” But that means you’re competing with people who actually went to art school. It’s a hard left turn to take in two years with a curriculum that’s so project-focused. It’s not impossible, but you have to do it around the curriculum, whereas if you go to art school you’ll get fundamentals. You’ll get color theory. You’ll get life drawing. You’ll build the foundation.

It’s hard to do a left turn away from something, which is why we’re primarily a grad program right now. People are coming to us with skills that we assume you’re going to build on from there. If you have a background in tech, you want to be a programmer and build on that. We can help you become a programmer with a technical artist focus, a game design or experience design focus, or storytelling.

A big thing people recruit from us are leads – producers, programming leads, someone with leadership potential because they went to grad school. We teach leadership as taking responsibility for yourself and your team, not just being the boss and telling people what to do.

When we see people coming from undergrad, at least they’re building on that. Then we start having conversations with them. Everyone gets assigned a mentor here. Our product, as it were, are graduates. We’re not saying, “Here, look at all our patents.” We have an education experience that turns out professionals, like Neil Druckmann from Naughty Dog. He’s one of ours. Kyle Gabler, who worked on World of Goo. That’s what we’re trying to do, turn out people who will push how we do things in new and exciting ways.

At a graduate level you’re building on something you did as an undergrad. Maybe you’ve had internships and stuff. That’s a big thing we push for undergrads. Think about internships so you can get in and dip your toe in the water. In some ways, at a certain age we’re like, “Oh, all this in front of me is what’s possible.” Then you’re like, “Well, but I don’t want to do art school, and I know I don’t want to live in Delaware.” Eventually you find a tighter range. “I’m interested in here. Science and art, that’s not bad. Maybe biology?” You get a sense. Sometimes it’s easier—even if you’re not sure exactly what you want to do, you know what you don’t want to do. That can help you start focusing in. We do a lot of mentoring around that.

In undergrad here, have they told you about IDeATe? It’s a horrible academic acronym. I think it stands for Integrative Design, Arts, and Technology. It’s cross-discipline minors, Whatever your major is. BXA is kind of the Cadillac of that. Anybody can take an IDeATe minor, though, and I think there are eight – game design, animation, mobile, robotics, entrepreneurialism, others. The business school used to have an entrepreneurial center, and last year an alum named Schwarz gave like $33 million to turn the business school’s entrepreneurial center into the university’s entrepreneurial center. They’re really supportive. You can go there with an idea and they’ll help you start a company and build on that, complete this project above and beyond your studies.

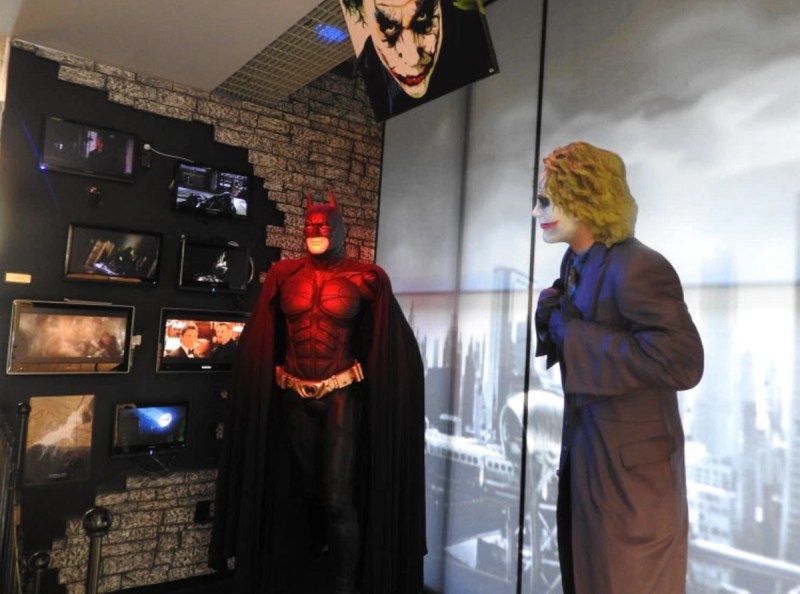

Above: The Entertainment Technology Center is a colorful place.

GamesBeat: Getting more and more startups coming.

Davidson: CMU students own their IP, which is fairly normal, except in some cases. At MIT you don’t own your IP. You sign it away to go to school there. You can transfer and make money. But with CMU you own it 100 percent.

It’s fun, on an undergraduate level, thinking about those minors. There’s a game development club here. There are all kinds of clubs. Student-driven theater, if you get into that. Some of the weird stuff—there are weird fashion things happening. What’s cool about CMU that I think we take a lot of pride in is, our science is good, but so are our arts. People start to interact and cross over.

We sometimes miss out on that down here. The reason we came down here—all those projects I was talking about, we have rooms big enough that they can sit together, like a little mini-company. Team six, here’s your office. You’ll live there for a semester. They probably spend 80 hours a week working on their projects.

GamesBeat: Has it always been down here, away from campus?

Davidson: No. When it started we were up on campus in the attic and basement of the computer science department. I don’t know if you’ve seen their building, but it kind of looks like a WWII bunker. I wasn’t here when it was founded. I was in Texas. My dissertation advisor was a woman named Sandy Stone, who was friends with both Randy and Don. We knew when the ETC started because I was studying with her, specifically because she had something called the ACTLab. It was very similar to the ETC, but it was smaller.

Between me doing those studies and those introductions—I’d worked in the industry and I had a PhD. I’d run some programs at universities. Don and Randy said, “Hey, do you want to work here?” And how do you say no?

Anyway, they started in any place that they could get. Then input from the industry, which is kind of common sense—they told us that our student teams would be more invested in doing better work if they could sit together, instead of sharing computer labs where they had to sign up for time. There was space down here, so we moved. It helped us coalesce into a center, as opposed to, “Well, there’s thing called the ETC, but it’s over here and over there and down here.”

Above: The lobby at the ETC.

GamesBeat: USC has multiple buildings, crammed in different places.

Davidson: It changes the vibe. But now there’s this big push to try to get us back up on campus. By nature we’re interdisciplinary, and we do a lot of collaborations on campus. “Oh, you should come up on campus, we have all these new buildings.” But space in the university is some of the most political stuff ever. And we’re big. We’re not the only tenant in here, but we have four floors, pretty much, full of 150, 200 students total, 50 faculty and stuff.

This was a past project. You get a sense of the range. Some students and faculty, years ago, said, “This is the range of the work we do. We think that’s our strength.” They made these little icons. This is metallic paint. They started creating a history wall of what they think is important. This represents what students across three years thought was a timeline of the program.

During that first semester they all sit here in the bullpen, cram ‘em all together. They bond. It gets moist. We have hygiene products. That’s boot camp. You survive it together. You mentioned the decorations. Don Marinelli, who came out of drama, is a big fan of trying to surround people with what’s out there. It adds excitement to the building, and it’s a way to challenge and inspire our students to what’s next, to what’s out there and big. We try to mix it up. We have a lot of alums in the industry, people at Disney and Lucas, so there’s a better mix now. Sometimes it was donated, or Don found it and liked it because he thought it represented some pop-culture moment.

This is usually where they eat. We have a lounge. There’s a class I teach where they’re required to play video games and then analyze and talk about the experience. We have two or three classes in board games, too, some with Stone Librande, who worked at Maxis for years on Sims and Spore.

Above: Star Wars characters at the ETC.

You can see out the window, and across the river, it was a huge steel mill. On this side they smelted all the steel. The boats would come up the river and drop off coal to heat the furnaces, and they’d ship it over on the “hot metal bridge” to the other side, where the boats were picking up steel. They’d shape it over there and take it out into the world. That’s how big a logistical design it was. Then, when that all went kaput, with a lot of funding they turned all this into a research park. Pitt has a building down here. Switch and Signal. Across the way it’s retail and restaurants. Forty years ago Pittsburgh was Detroit. I wasn’t here, but they recovered. It just took a while.

We have a lot of people who’ve gone on to Pixar. A lot of kids want pictures with this. He’s just Styrofoam, and one time this kid touched it. Spiders had laid eggs, so the kid touches it and all these spiders fall out of the. They all screamed and I thought, “Oh, that’s so perfect.”

The mix we have in the student body, we have to mirror that in the faculty. We have faculty from technical backgrounds, artistic backgrounds, design, industry. Most of the faculty are here. Here are current projects, and what our alums are up to.

Building Virtual Worlds, this is from that class I was telling you about. A team of five made two of these in two weeks. You put them on the floor and two players stand on one. You cooperatively compete against each other. Part of what’s fun about Building Virtual Worlds is we get them out of their comfort zone. They’re not allowed to use standard input-output devices. They have to use the weird stuff we have around or make their own.

Anthony Daniels is on our faculty. He’s a visiting scholar, along with Michael Keaton, who’s a native. Anthony came because of the Robot Hall of Fame. He was an MC for the Robot Hall of Fame, a joint initiative between CMU and the Science Center. It has two branches: entertainment robots and industrial robots. The idea being that entertainment robots inspire industrial development. He came to CMU one year and Don talked him into visiting. He’s an amazing critic. He can articulate why what you’re making doesn’t work for him.

Above: Batman and the Joker at the Entertainment Technology Center.

GamesBeat: Our GamesBeat conference last year was a bit like that, about the meeting between science fiction, games, and tech.

Davidson: I love stuff like that, where it gets a little interstitial? That’s where some of the best, most interesting stuff happens.

Up here, if you see colors, it’s us. If it’s white—you’re going to start seeing hazmat showers. Our colleagues are biomedical, so they do a lot of work with materials where, if the alarms go off, you get out of the building now. Here’s a project room, where they sit together for a semester. A lot of the project teams are over here.

You might find this interesting. We have an experimental publishing imprint called ETC Press. We started it about 10 years ago now. At the time there wasn’t really a good academic forum to talk about games. Nobody was publishing in the field. With the support of the provost and the president, we said, “We want it to be open access. We want to have this connection between industry and interdisciplinary work.” Brad King — he worked at Wired – his background is in the industry as a writer and editor, and then he got into academics. We hired him on as a full-time editor to evolve ETC Press beyond a small experimental thing and really represent CMU.

Have you heard of Give Kids the World? It’s a non-profit theme park in Florida affiliated with Make-a-Wish. A lot of kids who want to go to Disney World through Make-a-Wish, they stay there, because it has facilities to handle kids with disabilities. But some of them are so sick they can’t go to Disney, so they have a theme park at Give Kids the World that’s held together with donations, duct tape, and a lot of love. Mickey visits every day. Bugs comes from Universal.

We’ve partnered with them so once every year or so, we go down there and refresh their exhibits. It gives our students great design challenges. A big thing we’re trying to do, not to be too cliché, but how can we use all this to make the world better? We talk about the creative good. I want to make sure you meet Eric Brown. He and Asi Burak were the founders behind PeaceMaker and Impact Games.

Asi’s now doing Power Play in New York, and Eric is now our director of Alice, the brain research project. It’s still going, the little blocks of text teaching kids how to program. Ever since Randy passed away it’s lost market awareness to Scratch, but it still has millions of people around the world using it. We’re trying to decide—do we just open source it? Try to revitalize it? Depending on where we are now. But there’s so much happening now. Back when Alice started it was pretty much just Alice and Scratch.

If you’re not familiar, Alice is Randy’s old research project to teach kids how to program through storytelling and animation. It’s these blocks of text. You pull everything through the screen and below it it’s showing you the code that makes it happen. Eventually you can go down there and write the code and see how it works.

Above: Eric Brown is working on Alice, Randy Pausch’s project to make programming more accessible.

Eric Brown: The super fast elevator is that it was Randy Pausch’s. It was for VR prototyping, for non-technical people. It then moved on to being an early CSA tool at the same time as E-Toys and all of the block-based coding revolution. It’s been around since the late ‘90s — first as a “how to prototype VR” thing, then “how to author 3D worlds,” because that was also fresh and new. It’s continued on since. Now there’s a push to get us back to publishing for VR, because VR didn’t take off in the late ‘90s, but it’s making another attempt now. It’s at least more accessible. Transitioning from block-based to Java is one of the focuses, and object-oriented and things like that. It has that same space as Scratch or Snap or any of the other block-based ones, except for we’re in 3D, which kids respond to more in my opinion. Then we can layer tools for transitioning from block to text, which is one of the challenges. We’re making more and more of these early ed tools, but we’re not doing a great job of transitioning from what they learn there to other languages.

Davidson: One thing that Alice has always done really well is it’s always had a curriculum. It’s not just saying, “It’s fun! It’s out of school!” We develop lesson plans for using it. The community has returned that. It’s had such a storytelling component from its inception that it’s been very appealing and successful with young women and minorities. Some of the biggest successes that keep us going, everything is being used in the developing world. Stateside it’s all about Scratch, but in the rest of the world a lot of people have been using Alice because of the curriculum support, because of the storytelling.

Brown: Little things that have helped with that—Oracle is one of our big funders. They do Oracle Academy globally and use Alice a lot in that. Some of that is the ability for us to localize. What’s a detriment to us in some circles is we’re not web-based, but in places in developing countries where internet access isn’t as prevalent, the fact that we’re a desktop application helps us.

Davidson: We’re trying to give it a push, see what happens.

Brown: We’re sort of rebranding. We’re doing some stuff to wrap it back in Unity, to try and get it to VR and those types of things. We’re trying to get to Daydream and doing other research into how VR can be used to visualize and learn CS concepts. We want to do game competition stuff, because of my background with Impact Games. We’ve done a couple of competitions. One was in Romania, where they were sending me to judge stuff. A bunch of worlds were created that had a sort of anti-bullying context. We want to run some competitions using Alice for social issues stuff as well.

Above: A Mac sits atop an SGI Indigo workstation.

Davidson: Here’s a fun one, an SGI. Once upon a time they were so expensive.

GamesBeat: $20,000 or something?

Davidson: Now it’s just holding up an old Mac Plus. This is all stuff from Randy’s collection, the old virtual reality stuff from way back in the ‘80s and ‘90s. The first push of VR, when it wasn’t that great. We have an audio studio here, a green room with a visual suite. Wood shop over here, metal shop over there, a painting room with a fume hood. We have a full set of CNC routers and laser cutters. One past project, they had this idea of creating robotic puppets. So it’s not really a robot.

GamesBeat: Is that Jeff Katzenberg I saw in the video there?

Davidson: Yeah. He’s very charming. He was the man behind the curtain. There’s a pinhole camera in the nose, a wide-angle camera on the stand, and he interacts with the kids. He was like, “Can we get a robot to talk to kids about science in schools, get them interested in STEM?” The puppet’s gotten to a point where we don’t really ship him around anymore. It’s about 10 years old now. It breaks. But it’s amazing how much kids react. They gave him a birthday. But the whole story is developing a way of interacting with kids.

Above: Sonic hangs out in the hallway at the Entertainment Technology Center.

GamesBeat: How do you look at the relationship with Pittsburgh and the economic development argument?

Davidson: It’s interesting. One of the things I’ve found, students come here and they become charmed with it. That was my wife and I’s reaction. We moved here from Austin, Texas. Everybody knows Austin’s fun, but Austin’s way outgrown itself. We got here and we were pleasantly surprised. It’s a big enough city where there’s an infrastructure. There are good cultural institutions, a strong tech background.

It has an industrial focus. What I mean by that, we talk to a lot of VCs around funding games, and they’re like, “Well, we funded steel.” When an industrial project is halfway done you see half of what you need. When a game project is halfway done, that could be, “Well, we’ve iterated toward the right idea.” It freaks them out a little. It felt like they weren’t seeing anything happen.

But the students feel charmed. The cost of living and cost of doing business are crazy good. We have regular meetings with state government about more support and more incentives. Coming from Austin, there it went from not much to a big hub, and mostly because of Texas being so supportive.

GamesBeat: Jesse mentioned that there’s a film credit being extended to games soon.

Davidson: That’s a big deal. Of course, the film industry is like, “NO!” I’ve been pushing for them to do something. They did something like a million dollars for startups, which is great if you’re a student team coming out and you’re like, “Hey, 10 grand, we can try something.” But I’m like, “EA would move here if you give them the tax incentives that Louisiana or Delaware did.”

Above: Quasi the robot at the ETC.

GamesBeat: I guess the challenge is that your grads are high-level people, but they’re getting jobs elsewhere.

Davidson: Right. They’re getting courted. You saw Schell Games. There are probably about a dozen companies, and the IGDA has a really active chapter here. The opportunities are there. Having lived through it in Austin, there isn’t gravity yet. If you wanted to leave Schell, or they had to lay you off, you’d probably move to your next job. It’s not as if there are that many studios to go to, as much as I think that’s happening tech-wise. Games are getting there.

GamesBeat: At some point, do you think there will be more collaboration there, with the city and the state?

Davidson: We’ve done work for the state, and on state grants. [Game training company] Simcoach is excellent there. Some of their stuff is not only with the state, but being supported by the state to work with things like a local grocery chain called Giant Eagle. They’ve been making training games. You’re at a grocer and you’re checking out literal tons of groceries every day. It teaches safe ways to move heavy weights so you don’t get injured. We’re seeing a lot of that.

What’s fascinating for me, powerful me—being at Carnegie Mellon, we get invited to New York or Chicago or Los Angeles. Those cities are large enough that you can’t get people to agree to be in a room. Whereas Pittsburgh, you can get all the philanthropic organizations together for a meeting, or all the museums. Two of them, locally, started something that was initially called Kids in Creativity. “How do we support quality of life for kids? Education? What are they doing in school? How do we get parents’ support?” It was involved with funding from Gates and MacArthur and local groups.

Now it’s called Remake Learning. It has non-profits and schools and museums and businesses involved. It led to meetings where we worked with the children’s museum to build something called the Make Shop, a DIY hack lab for families. It’s been a huge success for them. It led to Maker Faire coming to Pittsburgh. It all started just by meeting each other.

Similarly we’ve done something with local school districts – one called Elizabeth Ford in particular, which at the time was the southernmost district in the county. If you get outside the city it gets rural real quick. They were, if not the bottom, then toward the bottom of school districts in the state. They had nothing to lose. They were willing to experiment. We worked with them on getting games into the curriculum, getting a smart lab into the school, getting a fab lab in their library. We got funding from MacArthur and a local foundation. Now they’ve risen into the top 10 in the state. The students are excited.

What was really inspiring on top of all that was hearing from their teachers. It took about a year, and some people quit. The librarian quit. She didn’t want a fab lab in her library. But just having college students hang out at the school while they were working on a project got their kids talking to our students. They started talking about college. These kids had never talked about college, particularly the girls. They met girls who were programmers and wanted to be like them. They’d never met anyone from another country. They started wanting to travel. It’s crazy, the impact you can have just by taking a field trip. We do once-a-month tours now where we take a day, visiting schools and Girl Scout troops, stuff like that. Civically, that’s a big part, and educationally.

Business-wise, there’s the Pittsburgh Technology Council that we’re a member of, focusing on the creative industries. We’re in all those meetings where we talk to the state. There’s recruiting. There’s VC support and angel funding, so a lot of students will stay. The hope is that if they fund you, you’ll stay in Pittsburgh. There are incubation spaces, co-working spaces happening now.

Above: Drew Davidson shows off a big Nintendo controller at the ETC.

GamesBeat: Getting the economic flywheel going, so to speak.

Davidson: Right. Google’s coming here big-time. Uber came in in some interesting ways. They stole the whole robotics department. You’re seeing a synergy there. They’re rebuilding. It used to be that Pittsburgh was a steel town. When I moved here from Austin—Austin self-promotes to a fault. They’re the capital of everything – music, whatever. Pittsburgh civic attitude is like, “We used to be great.”

That’s spun around in the last 15 years to “eds and meds.” Educational opportunities, the universities and the medical centers here. It’s boomed in different ways.

GamesBeat: Are there really 36 institutions of higher education here?

Davidson: There are. I wanted to show you this, all our ETC Press publications. They’re all free for download, public access. We partnered with Lulu way back when, though. That way we don’t have overhead. That enables us to allow for open access. We did all those “Well Played” books back in the day. Deep dives into things like, “What makes a video game work?” It was so popular we turned it into a journal.

This is the book I really wanted to show you, though. We had a colleague from the business school four years ago doing a study on how we teach creativity. Her expertise was in small-group innovation. She got a grant and they studied more than 60 projects, hundreds of students, and just unpacked what we’re doing, what works. When they started publishing the results and the data, that helped us quantify and unpack how we teach and try to support creative work.