Minoru Kidooka is in the middle of a soccer field just outside the Nissan Stadium in Yokohama, Japan. Dressed in black pants and a bright red shirt, he stands at the front of a tight formation made up of his employees, with his feet slightly wider than his shoulders and his right arm raised to the sky.

After spending the last four months rehearsing a complicated dance routine in their spare time, the day had come to finally show it off.

The result is the “Arc System Works 30th Anniversary Theme Song” and the hilarious music video that accompanies it. The quirky anthem is a fitting tribute for the long-running Japanese studio, which is best known for stylishly fun and off-kilter fighting games like Guilty Gear, BlazBlue, and most recently, Dragon Ball Fighterz.

A big reason it’s been able to survive this long is because of Kidooka, who is the president, CEO, and founder of Arc System Works (Arc is an acronym that stands for “Action, Revolution, Challenge”). During a trip to Tokyo last summer, I visited the company’s Yokohama headquarters and interviewed (via translator) Kidooka, chief creative officer Daisuke Ishiwatari, and chief development officer Toshimichi Mori about the past three decades of Arc’s history and to find out where it’s heading next.

Arc’s path through the industry — spanning multiple console generations and huge technological shifts — hasn’t always been easy. But as I spoke with the three veteran developers, who sat together behind a long table filled with art books based on their games, it was clear that they weren’t satisfied with their achievements. They were hungry for more.

A fortuitous fallout

Kidooka founded Arc System Works in 1988 after leaving a six-year stint at Sega. At the time, the Japanese gaming industry was shifting its focus from arcades to home consoles because of the success of the Nintendo Entertainment System (known as the Famicom in Japan). Kidooka saw a huge demand for console games, and he wanted to start a studio that’d embrace this new era.

That didn’t stop some of his initial cofounders (he referred to them as “the older generation”) from still wanting to work on arcade games. But Kidooka was adamant that they should make home consoles their priority. Unable to reach a compromise, he and other like-minded colleagues split off on their own.

“If you guys want to make arcade games, you can do that. But we think the future is with the NES,” Kidooka recalled telling his former coworkers.

Above: Arc shares its building with several other businesses.

Arc System Works’ early portfolio consisted of work-for-hire projects, many of which involved porting arcade games to consoles. It partnered with Sega to bring the side-scrolling beat-em-up Double Dragon to the Sega Master System, and made NES versions of Namco games like Final Lap and Rolling Thunder. Arc had 10 employees at the time, with Kidooka doing most of the programming himself due to his engineering background.

It wasn’t until a few years later — when Sony decided to challenge Sega and Nintendo in the competitive console market — that the studio began creating its own original properties.

“The idea of making our own games came right around 1994, when Sony announced the PlayStation. We still ported games and did work-for-hire at the time, but PlayStation introduced the CD, a new medium that had lower risks, lower manufacturing costs,” said Kidooka. “And we thought, ‘Hey, this might be a good opportunity for us to start trying to make our own games.’”

A fight with Bandai further convinced the developer that it was making the right move. Everyone in the room laughed as Kidooka brought this story up. When I asked him to clarify what he meant, he said that the situation was a little more nuanced and that it involved two specific incidents.

“First, there was a game we were developing with Bandai at the time, and we couldn’t squash all the bugs in the game. That wasn’t really a fight. It was more apologetic and saying, ‘Hey, we did our best, but we couldn’t eliminate everything,’” Kidooka explained.

“But the other one was with Sailor Moon. We were in discussions about making another Sailor Moon, but they insisted on making it in 3D. [We told them,] ‘We can’t do that. If that’s the case, then we can’t take this job.’ So they weren’t too happy about that.”

Released on both the Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis, Sailor Moon is a side-scrolling adaptation of the popular Japanese cartoon series. But perhaps more important than that, it’s — as Ishiwatari pointed out — the first fighting game Arc ever made. In retrospect, Sailor Moon was a harbinger of things to come: Today, the Arc System Works name is synonymous with anime-based fighting games.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8EhMCW_e5I0

Between the exciting potential of the PlayStation and an eagerness to control its destiny, the studio started exploring its own original ideas. But Kidooka and his team had no clue what to do. They tried making all sorts of games in different genres, such as the 3D mech game Exector, dungeon crawler Wizard’s Harmony, and a variety of dating sims.

“Really, it was in ’98, when Daisuke made Guilty Gear — that was the one original game that put things in motion [for us],” said Kidooka.

The birth of Guilty Gear

Daisuke Ishiwatari is a modern-day Renaissance man: He’s an illustrator, a musician, a game designer, and when the occasion calls for it, a voice actor. It is through his multi-disciplinary talents (along with a love for rock and heavy metal) that the Guilty Gear fighting game series was born. He came up with the idea for the game while he was attending Amusement Media, a trade school in Japan where students can learn about all aspects of game development.

“When I first decided to go into the entertainment industry, I picked the games medium because at the time, games weren’t nearly as complicated as they are today,” said Ishiwatari, who’s now 45. “And I thought I could dabble in many different fields of entertainment simultaneously.”

When he joined Arc in the mid-’90s, some of his first projects involved making pixel art for Wizard’s Harmony and being a quality assurance tester on Sailor Moon. At the time, Ishiwatari was a fan of Street Fighter and Fatal Fury, both of which were loosely based on real-life fighting styles and locations. But for Guilty Gear, he envisioned a fighter that had more panache, with a look and style reminiscent of anime and manga drawings.

He pitched the idea to Kidooka, who simply told him to give it his best shot (the Arc president likes to think it was fate that brought them together). Ishiwatari took on a lot of the work himself, writing the story scripts, designing the characters, and composing the rock-infused soundtrack.

Guilty Gear came out for the PlayStation in 1998, first in Japan and then in the U.S. a few months later. Critics praised its “unrivaled animation quality” and “kick-ass aural experience.” But while the first game was a good foundation for the series and earned a small following of hardcore fans, it didn’t take off as much as later entries would. Some people, Kidooka recalled, were wondering why Arc was still making 2D games when seemingly every developer was moving into 3D.

Above: The first Guilty Gear for the PlayStation.

With support from publisher Sammy (now known as Sega Sammy), Ishiwatari and his team moved on to make the sequel, Guilty Gear X. Originally released in Japanese arcades in 2000, ports of GGX eventually came out for Dreamcast, PlayStation 2, PC, and even Game Boy Advance.

“[GGX] really put us on the map and showed that, hey, we can make a good fighting game,” said Kidooka.

Guilty Gear became Arc System Works’ signature franchise, leading to a plethora of updates, spinoffs, and sequels in the years since GGX’s debut. In that time, it developed a reputation for being a pretty series, yet one that’s difficult to get into due to increasingly difficult gameplay mechanics and concepts. The developer also continued to work on other fighting games, including Sengoku Basara X (a spinoff of the Capcom action series) and Fist of the North Star (also based on an anime).

But in the mid-2000s, with the imminent arrival of a new generation of consoles, Arc decided that it was time to create its next original property.

“We did everything we could with the Guilty Gear franchise at the time; the last one that we worked on was [Guilty Gear XX] Accent Core. With every upgrade, every change we made, the game became more and more of a niche title,” said Kidooka. “The community and the fan pool got smaller and smaller with each upgrade. And the barrier to entry became higher for new players to join.

“The PlayStation 3 was coming around, and everything was becoming HD. … And that was when we realized we needed to take advantage of the next-gen consoles and their power.”

Going beyond fighting games

This time, Kidooka turned to Toshimichi Mori for ideas. The designer had been working at the company for a few years, helping out on games like Accent Core and Guilty Gear Isuka. Coincidentally, he also studied at Amusement Media for game design — but mostly because a Japanese idol he admired would occasionally give lectures there.

That’s where he first met Ishiwatari, who was one grade above him. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship that, at times, can resemble more of a rivalry (especially once their respective franchises took off).

The timing for Arc’s new project couldn’t have been better for Mori, as the team that was working on Guilty Gear XX Slash were free to move on to something else. Together, they set out to make a high-definition 2D fighter that would be easier to get into than the studio’s previous games.

“I thought the Guilty Gear franchise became too difficult as a game,” said the 46-year-old Mori. “I wanted to simplify a lot of it, to kind of reset the fighting game platform.”

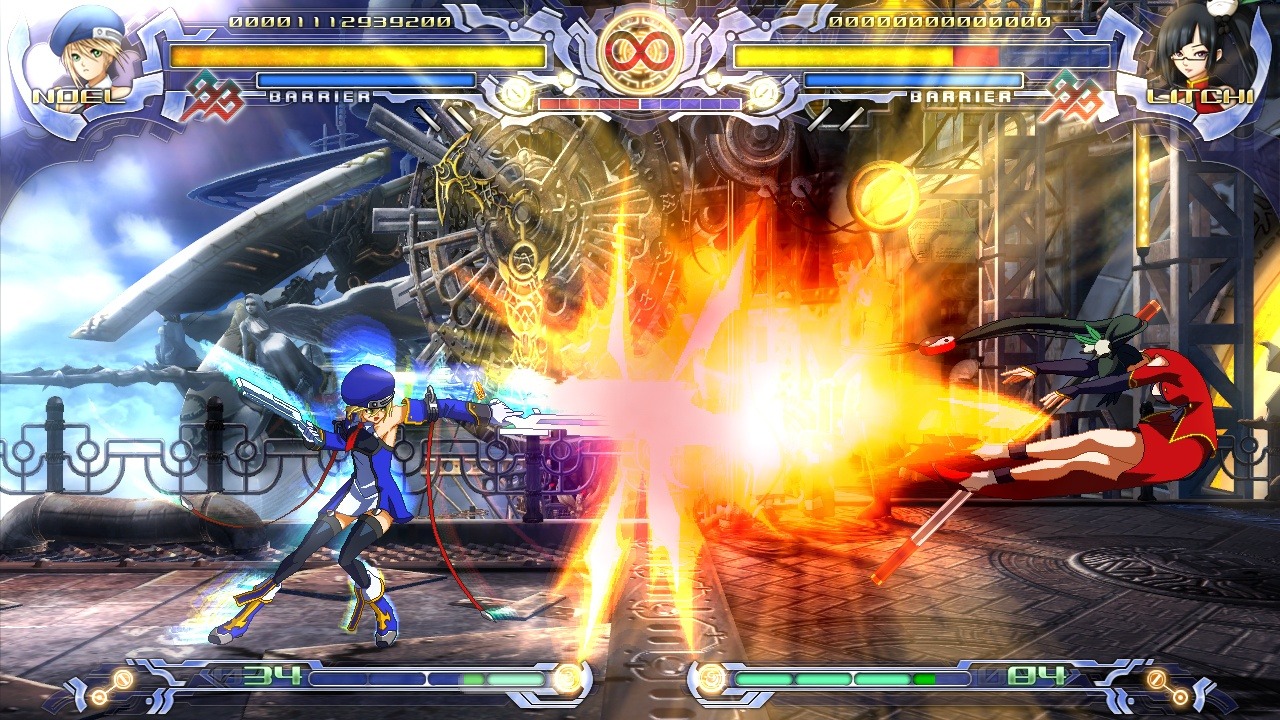

That philosophy led to the creation of BlazBlue: Calamity Trigger, which came out in arcades before heading to PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 in 2009. In addition to having a simpler control scheme, the game built on Guilty Gear’s legacy by combining gorgeous 2D animations with off-the-wall characters and flashy combos.

Above: BlazBlue: Calamity Trigger was Arc’s first HD fighting game.

While BlazBlue would also wind up having several sequels and iterations (and like Guilty Gear before it, added complicated move sets and techniques), Mori had much bigger aspirations for it beyond just video games.

“Instead of thinking of it as just a fighting game, I wanted to turn it into a single piece of content, an [intellectual property]. And that way, we can deploy it through many different mediums because we have a lot of cool characters here,” he said. “Fighting games were still a very niche genre back then, so it really needed to have its own identity where it would be able to translate to multiple mediums aside from just a fighting game.”

Shortly after Calamity Trigger’s release, BlazBlue plot lines and characters started popping up in other forms of media, including manga and anime. This broader type of thinking wasn’t limited to Mori’s series, however. In 2007, Arc System Works was in the process of becoming a publisher as well. At this point, the studio had 50 employees, and Mori said they were having a lot of discussions about how they should sell and market their games.

They also started hosting their own gatherings for the press, like they did in Shibuya with Japanese actress Kaori Manabe for the launch of the PlayStation Portable game Guilty Gear Judgment.

“We started doing a lot of exploring, including having our own events and trying new and different things we wouldn’t normally have done if we were just developers,” said Mori.

Everyone was so busy with development and publishing that Arc’s 20th anniversary in 2008 passed without much celebration (it rectified that in 2013 with Arc Fes, a party held in Yokohama with 6000 fans). But the late 2000s was an important moment for the studio, as it was only then that the developers felt like they were starting to cultivate their own identity.

“Instead of being this weird developer-publisher hybrid, we focused on [being] a publisher who can also develop in-house,” said Kidooka. “BlazBlue and Guilty Gear became the pillars for us, enabling us to find that Arc brand of publishing.”

The company’s publishing slate has since become an eclectic mix of studios and genres. Most recently, it released The Missing: J.J. Macfield and the Island of Memories, a puzzle-platformer from famed Japanese developer Hidetaka “Swery” Suehiro; and anime fighter Under Night In-Birth Exe: Latest from indie studio French Bread.

Above: The Missing is a collaboration between Arc and Swery’s White Owls studio.

Embracing their big moment

The only thing Arc was missing was a rock anthem.

But Kidooka could’ve never predicted the elaborate music video they’d film for their 30th anniversary. He just thought it’d be fun to have an official song that represented Arc System Works, a common practice among companies in Japan. He said their idea for the anthem “started to transform and take its own shape,” especially after an employee suggested that they should also make a music video. Naturally, it was Ishiwatari who composed the catchy tune.

While the developers had a lot of fun preparing for their performance, Mori — who fights against one of his BlazBlue characters in the video and loses — is still a bit miffed that the hardest part of their choreography ended up on the cutting room floor. The fans seem to appreciate their effort; during a party at the Evo 2018 fighting game tournament in Las Vegas, Kidooka and other staff members performed their dance in front of a raucous crowd.

Above: Fighterz has been especially popular among competitive players.

Though made to celebrate the company’s history, the anniversary song also illustrates just how big of a year Arc System Works had in 2018. Dragon Ball Fighterz, developed in partnership with Bandai Namco, was a critical and commercial hit, selling a combined 3.5 million copies between retailer shipments and digital purchases.

Fighterz is the ideal marriage of Arc’s striking 2.5D gameplay style (which first debuted in 2014’s Guilty Gear Xrd) and a classic anime franchise that resonates well beyond fighting game circles. It drew a big crowd at Evo 2018, with a climactic final bout between two of the fighting game community’s most well-respected pros: Dominique “SonicFox” McLean and Goichi “GO1” Kishida.

In May, Arc released BlazBlue: Cross Tag Battle, its first crossover fighting game, and one that harkens back to Mori’s original goal of making BlazBlue an accessible experience. The designer described it as an experiment, a challenge for the team to do something new and different with the 10-year-old franchise. He was trying to embody the “Challenge” pillar of the company slogan.

Kidooka said it’s a special time for the studio, noting that what was once a small, primarily Japanese fanbase has grown into a worldwide audience. The company’s increased presence overseas is a reflection of that globalization: It opened an office in Seoul, South Korea in 2016, and an American branch in Torrance, California a year later. In total, Arc has 200 employees.

“We’re able to give back to the community and a lot of the creators who contributed their blood and sweat to 30 years of history,” Kidooka said. “I think now is a really big moment for Arc System Works. Now is the time we really have to work hard!”

“We’re working really hard, Kidooka!” Ishiwatari playfully added.

When it comes to the company surviving for three decades, the president credited the team’s tenacity and their attitude of never giving up, saying that Arc has had just as many failures as successes. Staying laser-focused on making games also helped. But this doesn’t mean they’re afraid to rethink their approach.

If Arc System Works is to stick around for another 30 years, Kidooka reasoned, it needs to stay flexible enough to respond to rapid changes within the industry.

“Having a fun game is really just [the beginning]. All the games out there are really well-made and really fun, so how do we add that extra flavor, that extra element that will capture attention and create a memorable experience for a lot of fans?” said Kidooka. “I think we’re going to have to really evolve and be aware of not just game development — creating something fun that stands out — but the promo side of it, the marketing side of it, how we bring these games to people.”

Above: CrossTag is a mash-up of several different franchises, including Persona and Rooster Teeth’s RWBY.

The Arc Revo World Tour, a global fighting game tournament centered on Guilty Gear Xrd: Rev 2, BlazBlue: Cross Tag Battle, and BlazBlue: Central Fiction, is one example of this plan. Top players from regional competitions will head to Los Angeles this fall for the grand finals event, where they’ll compete for the $100,000 prize pool.

“We’re in an era where you can’t sell a packaged game and call it a day. … I’m not just talking about simple updates, but the different ways people play: being aware of the World Tour, seeing a game as a piece of content, an IP, and deploying it into other mediums,” Kidooka said. “With the internet having evolved as far as it has, we really need to approach each game with a very wide perspective.”

Preparing for the next three decades

As Kidooka and his colleagues ponder the modern business realities of releasing a game, creatives like Ishiwatari and Mori are thinking about the future of their franchises and how they should encourage the next generation to take the lead.

Both developers are well-aware of how hard Guilty Gear and BlazBlue have become for the average player. But at the same time, they believe that the genre has room for more accessible games that are still a lot of fun to play. One of the big discussions they’re having at the studio is what a game like that might look like under the Arc brand.

“Among our different teams, we talk a lot about what kind of taste, what should the feel, what should the color of each game look like,” Ishiwatari said.

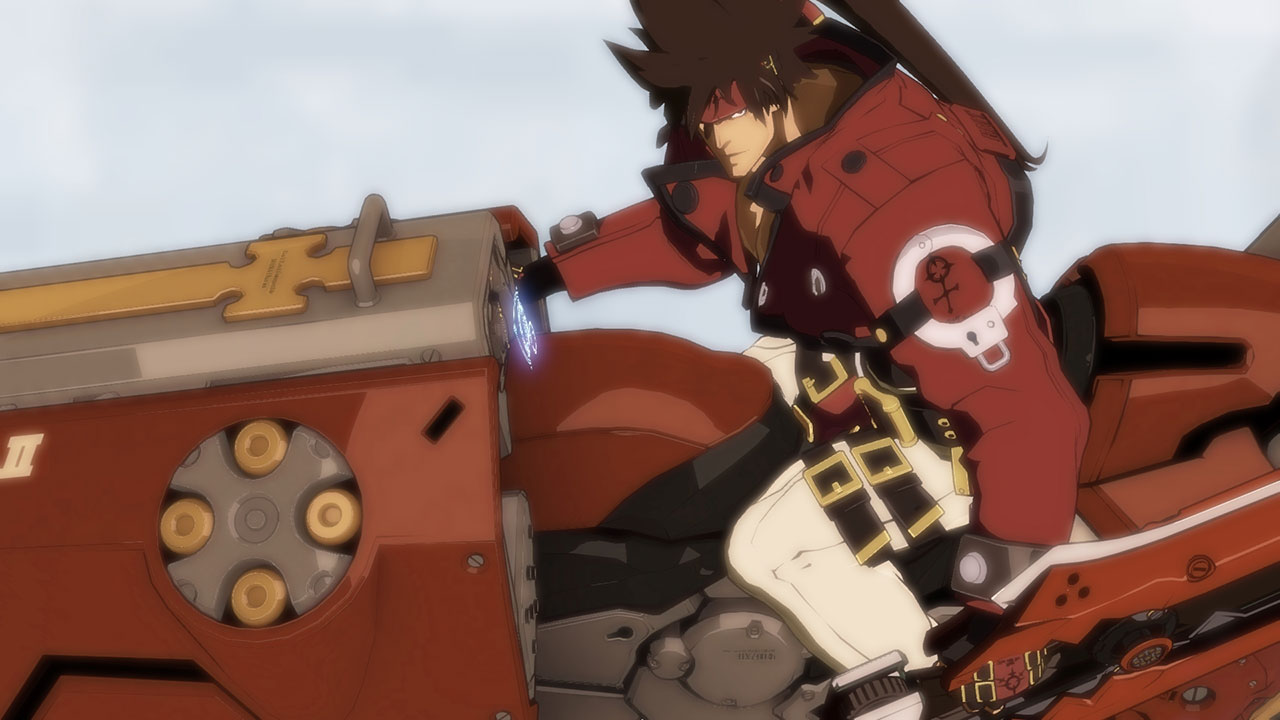

Since style and presentation play such an important part of its games, Arc is also trying to figure out what its next big visual hook or aesthetic might look like. It doesn’t want to repeat what it’s done before. Ishiwatari said that BlazBlue “mastered and completed that 2D visual design and style of expression,” and that Dragon Ball Fighterz “perfected” the hybrid 2D-to-3D gameplay from Guilty Gear Xrd.

He used a train track analogy to explain his thought process: With the 2D and 3D “tracks” reaching their final destinations because of BlazBlue and Fighterz, he’s eager to find a third track, one that represents a new kind of style that the team can build on.

Above: Sol Badguy in Guilty Gear Xrd Revelator.

“I want to keep the two tracks that we laid in the past — definitely keep those alive — but what’s the new, unseen track that we can switch to?” said Ishiwatari. “But maybe one day, we’ll come full circle, and we’ll go all the way back to the 2D track. I don’t know!”

Whatever game that ends up going down this new path might have nothing to do with their two biggest properties. To continue its momentum, the studio will need its younger designers to dream up new games and universes — just like Ishiwatari and Mori did with Guilty Gear and BlazBlue. Both men attributed Arc’s longevity to the free and open-minded culture that Kidooka established, one that encourages employees to bring new ideas to the table.

“I know it’s easy to look at Guilty Gear and BlazBlue because those are our two flagship games,” said Ishiwatari. “But part of me is hoping and expecting and looking forward to the day when one of our younger creators comes up with a brand-new IP — that will be the third, fourth, fifth, who-knows-what pillar — to support Arc as a company.

“But I still need to work really hard right now so I can stay as their mentor when that day comes. [Laughs]”