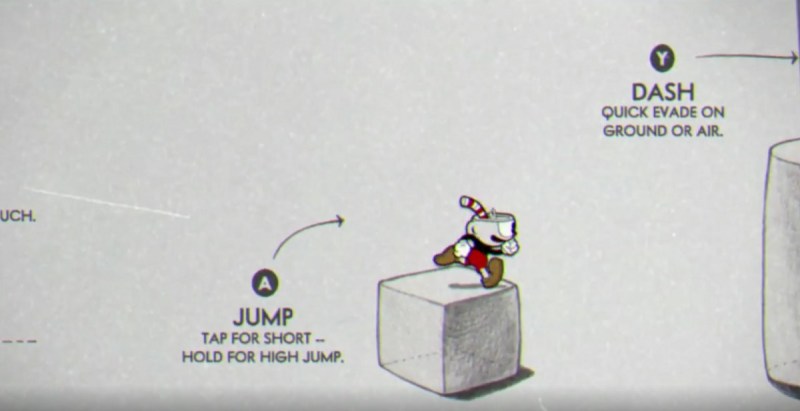

Above: Cuphead’s tutorial is different in the final version.

GamesBeat: I noticed that there isn’t really one good response to it. All these people are different. You say one thing to one person and it seems to work. You say the same thing to someone else and they just go postal on you. It’s puzzling that way, figuring out how to respond.

Quinn: After three-ish years of this stuff, I’ve come through so many different iterations of how to respond to any kind of controversy. I’ve had stuff that was completely made up from space, more or less, to stuff where there’s just enough out there that could look bad, if it’s framed in a certain way.

It’s funny, because I got into games because I didn’t want to be a performer or anything like that. I’m comfortable making art in a way that doesn’t require me to go out and be a personality. I didn’t want to be an announcer or an actress or anything like that. To have this public persona and have to give statements—it feels like a weird press conference sometimes.

At first I was trying to respond very engagingly: “Here are the facts. This is what actually happened.” That didn’t work, because people already had the next talking point in their head that they were going to use. They weren’t engaging in good faith. They just wanted to yell at me or try to embarrass me or make me have a specific emotional reaction or get me to block them. People try really hard to get me to block them so they can screenshot it and brag about it. I just mute people. I don’t want to engage with that kind of thing.

But I tried going with facts and it didn’t go anywhere. I tried talking to people directly, not addressing their claims, but asking, “Why are you like this? Are you okay?” I was a jerk teenager once who was super into games. I remember what that felt like. Maybe if I try to deal with the root cause here, that’ll work. Well, that had mixed results. The response to someone would be turned into some conspiracy theory by someone else.

After a while I was responding with—I had this big folder of, any time you play a fighting game and the round is over, early ‘90s fighting games, there’d be that win screen. You’d have the character doing a pose with the one line of trash talk. “Looks like you weren’t good at that!” I’d just respond with those screenshots, and the arguments they were having would be the same on their side as when I was trying to respond with facts. “Oh. It doesn’t matter what I say at all.”

Now I try to respond about larger points, to take focus off of individuals who are bad-faith actors. There’s some value in talking about specific things, for third parties who are watching what’s going on. Maybe it’s people who have been targeted by harassment themselves, who’ve been through this sort of thing and don’t know how to respond. I try to think of them as the audience and talk to them, talk to people who do want to engage in good faith, instead of trying to play whack-a-mole with weird accusations and conspiracies and misinformation, or people who just don’t like you dressing stuff up as being something that it’s not.

Above: One of Zoe Quinn’s games.

GamesBeat: It does seem like, if you try to talk to someone on the other side, you never really know how it’s going to go. It could be dangerous to do that. It makes you want to stay in your side of the social media divide, I guess.

Quinn: After they got my phone number, I used to answer, for a long time. My dad’s really old-fashioned. He has a hard time updating phone numbers and things like that, and I didn’t want to lose contact with him. I used to answer, and people who weren’t automatically screaming off the bat would say, “Is this Zoe Quinn?” “Yeah. You dialed my number. I don’t know what you thought would happen.” “Oh. You know your phone number’s on the internet, right?” “Yes. I’m pretty well aware.” “Oh. I’m sorry.” Some of them would apologize, because they just didn’t think it through that far.

Sometimes I can tell when I tell a particularly good joke on Twitter or something, because I’ll get an email or a Reddit message from someone who participated in Gamergate and they’re like, “Oh, no, while I was obsessively going through your feed and stalking you, you said something that made me laugh. I started thinking, you’re an actual person. I know that sounds weird.” And I’m like, no, I get that a lot, this dehumanization thing.

I try to think of ways I might subvert that, because it’s hard to think of other people online as being fully people sometimes. People get caught up in participating any kind of mob-like behavior, because it’s maybe the only sense of community with other people that they’ve had. If everyone in your group is doing it, it’s harder to pump the brakes and question why you’re participating in this sort of behavior, to feel the weight of what you’re doing. When someone is just an abstract symbol, or text on a screen, it’s harder to feel like what you’re doing to them might be hurting a real person, to feel the weight of that, versus just trying to play a game with your friends. “Who can mess with this person the most?”

GamesBeat: It seems like the precursor to some of this was Anonymous, the hacktivist group that was going after corporations, going after Sony. It was such a jolly time, taking down a big company, bringing their website offline. If you participated in that you felt a sense of community.

Quinn: It’s power, too. When I was younger, 15-ish, I was part of Anonymous, doing the whole hacktivism thing. I was pretty geographically isolated. Computers and the internet felt like magic at my fingertips. I was this little messed-up kid that couldn’t control very much in my own life, but with a computer I could do all kinds of stuff. It felt like having some kind of power or control. I feel like that’s definitely the case for people.

There’s a big difference between people who I, optimistically, think may be the majority of those folks, versus people who point the mob in different directions. The guy who started by pointing the finger at you, like. They know what they’re doing, to a certain extent. They have different motives – trying to build a brand, trying to monetize this through various means. That’s a bit different. I think all of this feeds into the same kind of biases that people have offline. It’s not as if the internet invented racism or sexism. It’s not as if people leave all that stuff at the door when they sign on. That’s always a factor too.

I feel like we’re in a weird point with the internet where we’ve made this extremely cool, extremely powerful, extremely unique thing, but we still have no idea how to treat each other online. Treat each other well, at least.

Above: Gamergate activity from Google Trends between 2014 and 2017.

GamesBeat: I feel like the people directing this will face some kind of karma. Haters eventually have to deal with the consequences.

Quinn: I always wonder when and how that’s going to come. A lot of times I think that community—if you build a community and a platform out of recreationally tearing people down, it’s not a stretch to think at some point someone might want to recreationally tear you down. Especially because so much of it—it’s such a weird thing to watch.

There’s one person I’m online friends with now who I only knew in the context of Gamergate. He reached out and took a pretty hard stand and was very friendly, in my corner. He said, “Hey, I don’t really know you, but I see what’s happening to you and it’s wrong. I know why you wouldn’t want to accept anything from a stranger, but let me know if there’s anything I can do to help you.” We were chatting because I’d read some of his articles, stuff like that.

We were talking about this one, basically, proto-shitlord, before social media was the thing everybody was on. He would do these elaborate posts about people who were “hilariously” messed up, write this big dossiers and be like, “Oh, look at this jerk.” Basically callout posts, but it was a different time back then. He said, “You know that’s our mutual friend so-and-so, right?” Like, what?

I went back to this new friend and realized, wait, hold on, you did all this stuff. He said, “Yeah.” He sent me this thing he’d written owning up to all that and talking about it how people did turn on him and were stalking him, stalking his wife. He said, “That’s one of the reasons I know how bad I can get. I know I have a lot to make up for. I want to try to make the world a better place now. I understand why people behave this way.”

It’s just a weird situation to be in. The thing about internet culture that worries me now is trying to figure out ways where people can step back from that. The path to becoming not a shitlord anymore, to making up for the harm you cause, is really undiscovered territory. The internet remembers everything forever, right? But what if someone does legitimately grow and change? We need to figure out ways to—without belittling the needs or the struggles of the people that person hurt, still sensing that. We can’t just tell people who’ve been victimized to suck it up. But ways to rehabilitate everyone and have better community practices that don’t just treat everyone as disposable.

Above: Zoe Quinn’s Depression Quest game.

GamesBeat: There’s an interesting realization that a lot of people should come to, though. There are a lot of little shitlords out there. All these seemingly innocuous comments carry a lot of weight when there’s enough of them.

Quinn: It’s the crux of it. The bigger your platform gets—it kind of feels like being Godzilla sometimes. You make a slight move and you can accidentally knock over a building. It’s a tough thing to navigate. I feel like—I can’t cite the thing, because I don’t remember where it was, but I recall reading a study about how our brains are wired up to only really know about 300 people. I have to wonder if some part of the difficulty in dealing with the repercussions of your actions on the internet is just that we were not ever really built for being able to conceive of a global community of anything.

It’s so cool that we’ve made this, but also, we’re still monkeys in shoes. Maybe we can’t fully wrap our heads around just how many other people there are. Or the butterfly effect any of our actions can have.