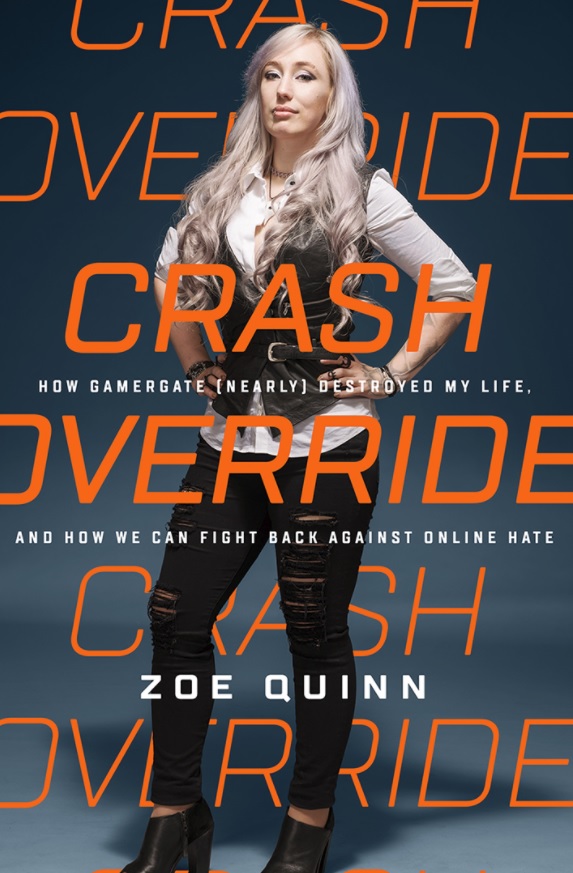

Above: Zoe Quinn’s book Crash Override chronicles her Gamergate experience and how she is fighting back.

GamesBeat: At another panel I heard an interesting thought, which is that toxicity is associated with anonymity. More and more, gamers and the communications systems that support gaming, are heading toward live communication, live interaction. If you’re a streamer and you’re a toxic person, if you use that kind of language in your stream, you get called out and asked to apologize by lots of people. It removes some of that anonymity from how you behave.

Hopefully we’re not scaring all the investors out of the room here. They’re scared of games already, in a way. We’ve always heard a phrase about investors fearing games because it’s a hit-driven business. They’ve shied away from trying to pick hits, the same way they’d shy away from trying to pick which Hollywood movie is going to be a breakout hit.

But in some ways — I know another investor, Jon Goldman, who invests only in games. The way he puts it, this is true of any investment. If you analyze any business, there’s only going to be one Amazon. There’s only going to be one Google. You take risks by investing. Gaming doesn’t have a double handicap in this way. You just have to pay attention and realize you may be taking a risk. I wonder if any of you have thoughts on this phenomenon.

Greer: Yes, it’s hit-driven, but those hits are really long-lasting. A successful game will last not just for months or a year, but for decades. We see that with World of Warcraft, Pokemon, Candy Crush. Almost any major game you can name has lasted and remained tremendously popular for years. Yes, you’re investing toward that one special game, but once you have a hit, you’ve created a profitable cultural phenomenon that can have really long-lasting value.

Levin: Part of the issue is, you have a culture and a DNA in a lot of the investment communities where they don’t have a track record or experience investing in anything content-related. The notion that a games investment would somehow differ from investing in a production company or a digital studio or a VR production entity—some of it is the shiny toy phenomenon. “Let’s invest in that that thing that’s getting a lot of attention.” Then it becomes part of their portfolio. It’s neither fish nor fowl, and inevitably, as companies do, perhaps they miss their number or miss a milestone or the market slows down. Then a lot of questions get asked around it.

The good thing is, as the games business has diversified and matured, you now have a group of investors who bring that pedigree and acumen and network and operational experience to the table. We have a bunch of those partners in deals we do: VCs like Ridge Ventures, Phil Sanderson there, or Gregory Milken, who’s a partner in at least two of our deals. Mitch Lasky. Index. The list goes on. You’re starting to get VCs that have multiple people within their portfolio of investors who bring in that perspective and experience. They better understand—to the point that was made, it’s the worst acronym ever, but GAAS, games as a service.

It rings true, because when you look at the number of titles that have now existed for five, seven, nine, or 25 years—Maple Story is a great example. It’s so far beneath the radar screen, but what an unbelievable story. That speaks volumes.

Above: Mobile gaming is half the global market.

GamesBeat: There are other investment strategies as well. There’s the picks-and-shovels strategy, or going up a level and abstracting to the platform level. Someone who’s shy about investing in a game might be more inclined to invest in a game platform. A lot of startups in the game industry have recognized this and pitched themselves as game platforms or toolmakers instead of makers of individual games.

Greer: We’ve also seen some interesting innovation from things like Kickstarter, where essentially the funding and investment for games is coming from gamers themselves. It shows there are maybe opportunities for investment from people who are already passionate.

Soqui: It comes down to why you’re investing. Not all investors are built the same. Some are looking for disruptive technology investing, because they’ll bet on 10 and one will win. Some are looking for steady, flat growth because they want to take risk out of their portfolio. Some of them have a diverse portfolio, where they’ll invest in infrastructure, invest in distribution mechanisms, and invest in a game itself. When you say investors are shy because it’s based on big hits—if that’s the type of investing you’re doing, you’re probably investing in the wrong thing, if you’re only focused on big hits. It sounds like you’re looking for just one win to make your portfolio.

Nothing else is like that. If you invest in real sports, it’s not like that — if you invest in advertising, distribution, leagues, merch, you name it. What do you invest in? What kind of portfolio investment are you? What are you looking for?

Levin: I do think esports has taken a page somewhat from what not to do. There’s a lot of dumb money being thrown at a bunch of team ownerships and being a foundational block in the standing up of some of these leagues. When you look at, for example, the quality of ownership that’s been put together around the Overwatch League, it’s a breath of fresh air. They went through an arduous process of filtering and editing and making sure they were making decisions based on strategic value, operational expertise, market acumen, all of these things.

You now have folks sitting around this table where there’s plenty of gaming DNA, global sports infrastructure operational DNA, licensing and merchandising DNA. These are areas game companies never played in before: apparel, shoe deals. All of these worlds that no one ever thought would collide are colliding. You want them to collide with the folks who have the acumen to act against that.

Some of the other publishers have just plucked folks from game operations, from that side of the house, and said, “Hey, now you’re going to run our league.” You wouldn’t do that in any other business. I’m not gonna go out and run a waste management company. There’s a learning curve. Maybe I could figure it out over time, but I would be a liability.

Esports, yes, we’ve talked about like it’s the shiny new toy. In the last couple of years VR was in that role. But I think it’s wildly different. The contemplative nature with which a lot of these folks are vetting their ownership speaks to that.

GamesBeat: We’ve touched on this notion that investors might be more interested in investing in something like games, plus something else. Something on the edge of the game industry. I brought up blockchain and cryptocurrency in games, but nobody on the panel wanted to talk about that. It’s a whole subject unto itself.

I’m one of those gamers who would like to see the metaverse happen. That’s a collection of worlds. It’s not just one worlds, but several virtual worlds. The way you would connect those worlds is through a cross-platform technology, and the transparency of blockchain, to me, seems like a necessary tool for that to happen. Tim Sweeney, the CEO of Epic Games, thinks that blockchain is one of those building blocks for the metaverse, and he thinks it will be buildable in a short period of time.

Soqui: I would say that blockchain is probably a contributing factor, but let me hypothesize something else, which is that if you want individuals to be part of this metaverse, and you want them to be able to create their own version of the metaverse as an add-on, and you want to democratize these things, I think distributed compute — being able to control my environment and hook it in to other environments — that whole backbone of infrastructure is what’s going to enable that to happen. Transactions and IP can be secured with blockchain, but fundamentally, you need a software and hardware architecture for something like that to happen.

Above: Ready Player One

GamesBeat: Blockchain is decentralized, of course, and that’s another interesting subject within games. I’m curious what you think about the forces that are democratizing and decentralizing the game industry, versus the forces that monopolize and centralize the game industry.

Soqui: Democratization is an extension of a shared economy. That’s a fundamental belief. When I make it easy for someone to do something with an asset that they have or they want to control, you get disruptive advancements. You get people doing what they want to go and do. There are companies emerging today that are starting to democratize what’s going on there.

It’s an intersection between some of the big players and some of the small players that are trying to democratize the development of games and the social interaction around games. Whether one wins or not, it’s just business economics. Once something becomes apparent that it’s democratized, like Samsar democratizing VR and the creation of VR content environments, someone’s going to want to invest in it. VCs will want to get in on that.

Things like that are happening. I don’t think it’s winner-take-all. I’m glad there’s democratization because that increases the total available market. Individuals can participate in an economy rather than just buying services in that economy.