The global games market is expected to grow from $137.9 billion in 2018 to more than $180.1 billion in 2021, according to market researcher Newzoo. The world has about 2 billion gamers now thanks to mobile gaming, which now accounts for half of all revenues.

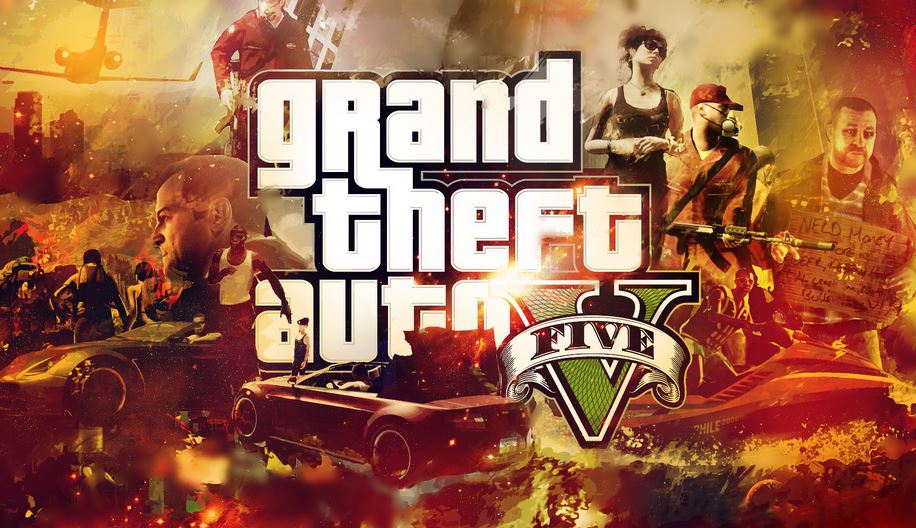

Just how big is this party going to get? We contemplated that question in a panel about games going mainstream in a session at the Milken Global conference in Los Angeles last week, where 4,000 investors and other VIPs gathered. Games, of course, are already mainstream, with titles like Grand Theft Auto V selling 90 million units and generating $6 billion in revenue.

Will the next big thing be virtual reality or esports or augmented reality or all of the above? Where will the next billion gamers come from? Our panelists answering those questions included Kathee Chimowitz chief revenue officer at BoomBit Games; Emily Greer, cofounder and CEO of Kongregate; Peter Levin, president of Interactive, Games & Digital Strategy at Lionsgate; and Frank Soqui vice president and general manager of virtual reality at the client computing group at Intel.

We also discussed attempts to make gaming more accessible and diverse, and whether the hardcore subculture’s clash with the mainstream casual gaming culture will hold the industry back.

Here’s an edited transcript of our panel.

Above: Peter Levin (left) of Lionsgate and Frank Soqui of Intel at the Milken Global conference.

Frank Soqui: I’m vice president and general manager for VR at Intel.

Peter Levin: I’m president of interactive ventures, games, and digital strategy at Lionsgate.

Emily Greer: I’m the co-founder and CEO of Kongregate, a games platform and publisher.

Kathee Chimowitz: I’m CRO for BoomBit Games.

GamesBeat: We all know games are big, but they do have some issues. We’ll get into some of that in this session, especially as we think about how we’ll go from about 2 billion gamers on the planet to maybe 3 billion or more. We know, according to Newzoo, that the business is about $138 billion in 2018, and that’s expected to grow to $180 billion by 2021.

Now, I have a trivia question for the audience. What’s the single most successful entertainment product of all time? Is it Star Wars? Is it Gone With the Wind? It’s actually Grand Theft Auto V, which has sold 90 million units worldwide and brought in $6 billion in revenue for a single title in a long-running franchise. Star Wars has had something like $4 billion. Peter can elaborate this on a bit, about the relationship between games and movies and how big things are.

Levin: The fact that we’re having the conversation is fascinating. GTA was able to compile $6 billion in revenue. But when you look at Star Wars, you have other areas of revenue generation: licensing and merchandising, theme parks, all these other extensions of the brand that have been very germane to that IP for decades.

A company like Lionsgate, when we’re able to adapt IP into multiple formats — film, television, and games — they support one another. They can be accretive to one another. A great example for us last year was Power Rangers. The film came out, and we had a very successful mobile game based on that IP that continues to live on. Should we continue to make Power Rangers films, we’ll have a built-in audience that we don’t have to re-create.

Coming back to the stats, the fact that there are titles that exist at the level in the game space — there are multiple titles. It’s not just GTA. There are multiple titles that have lived on for years, or decades in some instances. That’s a part of the narrative that a lot of folks aren’t familiar with, and would not have ever guessed.

Above: Asia more than half of the global game market.

GamesBeat: A much lesser-known game is Maple Story, from Nexon. It’s been running for more than eight years now. It’s generated $8 billion. That revenue comes from a free-to-play game. We’re getting into some distinctions a bit, but — it’s good to know from the start that gaming is not “going” mainstream. It is already mainstream. It’s already, in many ways, as big as any other kind of entertainment.

For some time, gaming has had a stepchild feeling to it, or some sort of inferiority complex compared to older forms of entertainment. There’s a lot less reason for that now. We can get into whether gaming is overcoming that. But I’ll throw something up in the air for everyone to talk about, starting with Kathee. How do we get to those next billion gamers?

Chimowitz: I’d say it’s mobile. Mobile gaming is 51 percent of that $138 billion this year. Mobile penetration is happening around the world. If you look at a place like Vietnam, it’s had double-digit growth year over year, 12 percent for mobile gaming revenue. Also, messaging. Facebook Messenger has games, as does WeChat. WeChat is the biggest messaging platform in China. A lot of people are playing games through these apps, and that number is growing quickly.

Greer: I agree, particularly when we look at how Android is exploding in developing markets. Android itself is probably going to be the single biggest game platform. As technology continues to improve — HTML 5 in particular is a very lightweight way of making games. It works on PC, mobile, the mobile web, and so on. It’s easy to make small, bite-sized games that are easy to deliver on poor connections. That’ll be important as infrastructure continues to improve. It’s also part of the foundation for messenger gaming.

Levin: I’m showing off my master’s degree in the obvious, but with the metrics we’re talking about, mobile is an enormous force. You have entire markets like the Indian subcontinent, where they are wide open. There is very little uptake of the types of phones and devices that will allow for qualitative gaming experiences. That alone is north of a billion. You’re talking about prospective markets, untapped, that are going to have access to cheaper hardware, software, IP. India is an English-speaking market. There’s a huge opportunity.

When you look at games like Arena of Valor, 300 million monthly active users was I think the last number? I’m sure it’s higher at this point. These are breathtaking metrics.

GamesBeat: Frank, you’re working in virtual reality at Intel. I’m counting on you to talk about something other than mobile games here.

Soqui: I will! Not to discount mobile. It’s clearly an awesome phenomenon. But I think a little differently when I think about the next billion players. I think about content. I think about architecture. When we talk about content, so many times we get to a space where something new is coming around the corner and we wonder if it’ll be the next big thing. Let’s say it’s VR and AR. Name your favorite technology. But what’s more important than the technology is the content. Is it telling a compelling story? We need a lot more content out there.

Sometimes we imagine that the big players are certainly going to win in the area of gaming, but just like you were talking about with movies, I think it’s a segment of the market where indie players are important. Content is important, content that rides across a variety of computing platforms. It’s mobile, PC, notebook, you name it. Anything that lets me play a game the way I want to play it on my favorite set of devices.

Above: Grand Theft Auto V is on fire on Steam.

The other thing is architecture. These are crazily immersive games and they have tremendous workloads. I want to stream. I want to capture my gameplay. I want a social experience. I want to interact in ways that I couldn’t interact before. Anything that makes me feel like I’m becoming more a part of that experience — that architecture, not only on the PC or mobile side but from cloud to edge to 5G, that we need to deliver the experience will be very important.

And then audience. We keep thinking about gaming, whether it’s real sports or esports, where it’s about the player. But it’s not only about the player. The audience is a huge part of why we’re doing what we’re doing. The audience being able to interact with the game, we’re on the verge of that, where the audience becomes non-player characters. The audience interacts with other audience members in a social kind of way. There’s a tremendous focus on audience because that’s who you’re serving.

There’s a ton of businesses that end up spinning around that audience, not the least of which is advertising, but also how they connect with each other socially, how they get advice on the latest gaming PC or mobile platform they’re interested in. When you hit all those three, you’ll start reaching those next several billion players.

GamesBeat: I sometimes measure what’s trending by what stories I write in a given week. I’ve written 15,000 stories at VentureBeat in the last 10 years. A couple of years ago I was writing VR stories every week, investments every week. Now esports has taken over. In some ways, VR didn’t live up to all the hype associated with it in its first generation. Frank, can you address what that means for the next generation, or whether VR is viewed by a lot of people as a kind of fizzle?

Soqui: The beginning of any technology hype cycle, there’s always this place in the curve, the “trough of disillusionment” or whatever you want to call it. There’s a lot of experimentation, a lot of high hopes. It goes through some active adoption phases and makes its way through that.

At Intel we view things like AR and VR as once-in-every-20-year phenomena. Before there was a GUI, there was just text. When the GUI came in, people said, “Oh, that’s just for kids. No one wants a GUI.” All of a sudden you can’t live without it. When touch came in, it seemed a little gimmicky. Do I want touch my screen all the time? Now you can’t live without it. When you can’t touch a screen today, if it doesn’t respond to you, you wonder if it’s broken.

The way we’re going to interact with compute is going to be through things like these realities, these immersive types of technologies. It’s going to change the way we interact with each other and interact with compute. To get all worried early on because it’s not taking off the way we overhyped it, that’s not the point. You look for clues about where it’s being used. It’s in gaming, entertainment, retail, surgical theaters. These types of realities are traversing segments like they’ve never done before.

To segue away from gaming a bit, there’s true ROIs that we’re getting on the commercial side. That’s why we’re still pretty bullish on the opportunity around VR. If you ignore the hype, I understand. Sometimes we like talking about things as if they’re going to take off tomorrow. But I believe this is a once-in-20-year transformation of how we’ll interact with compute.

Above: Peter Levin of Lionsgate and Frank Soqui of Intel

GamesBeat: Peter, you’ve been investing in VR, as well as a lot of other types of games. What’s your feeling about it?

Levin: Very bullish on the medium, as I’ve said a bunch. Very bearish on the timeline for commercial attraction. We’ve invested in some VR vehicles, but at every turn we’ve brought in platform players, hardware players, and endemics to mitigate our financial downside.

There’s a couple of reasons for this. One, very few people have a 10 feet by 10 feet space in their home to enjoy a qualitative VR experience. More and more people’s homes are starting to look like an airplane galley, or Bruce Willis’s apartment in The Fifth Element, compared to having that disposable footprint. For us, location-based entertainment was a priority from day one. You had a lot of aligned interests. You had big retail footprints that were looking for programming and content to house in that footprint as they were losing customers and audience to online retail experiences. You have movie theater chains and a host of other retail footprints. That’s been our priority.

We chose not to pull the trigger on investing in any one particular VR production entity. It was a deliberate decision made early on. For us it was about working with as many as we can, and if we find we interoperate well with one entity or another, we can contemplate a more strategic relationship. Part of our issue fundamentally was, these weren’t necessarily content-driven organizations. For us it’s all about storytelling. We’re a content-driven company, content first. As water seeks its own level within the VR space — again, we’re bullish on what the future has to bring with VR and AR, but we’re trying to be smart about how we can play against it.

Chimowitz: I don’t invest in VR or make VR games, but I’m a user of consumer VR, and I don’t see it as an experience at home. Again, you have to have that big 10-by-10 space. But I’ve been to an attraction called The Void, where you wear a pack and you can have an experience with a friend, just like being in a movie, and have fun being a Rebel soldier in Star Wars, fighting stormtroopers. That’s a good example of where VR is going.

GamesBeat: It’s interesting how some of the VR companies have pivoted into different spaces. They’re getting their games into VR arcades, where they can charge $5, $10, $15 per customer, as a way to get VR out to the public and in the hands of people who aren’t going to pay $1000 for a PC first, and then go buy something else to go with it, hundreds of dollars worth of VR headset. It’s an interesting pivot for VR companies.

Greer: I think VR is magical, but for it to go mainstream, you need to figure out how to make it work with our instinctive bodily reactions to immersion. The trend in media over the last few decades has been away from immersion and toward convenience, away from the movie theater toward home consumption. That’s something that VR needs to take into account. A lot of us feel uncomfortable when we’re disconnected with the world. When you try something like what Kathee’s talking about, where you go someplace and have this magical experience, when you step more consciously out of your normal world, it can work better than an in-home experience, the way the initial versions of VR have been presented.

GamesBeat: This week Facebook finally launched the Oculus Go for $199. It’s a stand-alone VR headset. You don’t have to plug it into a PC. It has no wires. You can take it with you and enjoy VR anywhere. Maybe that’s not the way Frank wants VR to happen, but it helps, right?

Soqui: VR is going to happen the way it’s going to happen. I’m a strong believer in a segmented market. There will be all-in-ones. There will be phones. There will be PCs and notebooks. There will be even more experimentation around headsets. I’m not really that worried about what may or may not be a piece of the ecosystem.

What I tend to think about is, these tremendous immersive interactive workloads put a lot of pressure on the data center, on compute performance, on graphics, on the network, on the edge, on 5G. Intel makes a lot of devices at the edge and we’ll continue to evolve those. I just see a bright future for what’s going in compute and the demands going on there. Every time we produce something new on the compute side, on graphics or storage, something like VR comes along to challenge the heck out of that. It creates more demand for what we’re delivering. But we’re comfortable that all-in-ones will do well.

GamesBeat: Speaking of a different direction, I’d like to play a video. Kathee will talk a bit about this and why she wanted to bring up the subject.

Chimowitz: SpecialEffect is a company that makes controllers for the disabled, modified for their needs. They even make chin controllers, which you might have seen, and they make their software available free for anyone in the world to play Minecraft online. We’re hoping that, one day, whether people are in the hospital, or at home with their family, they can play games and have the best possible experience for themselves and their families as well. It’s a multiplier. It’s an example of what the games industry can do for its community.

Above: Oculus Go is very comfortable.

GamesBeat: Kathee and I got into a discussion about this offline, and I thought about playing a bit of devil’s advocate here. We’re talking about getting games into the hands of the next billion gamers. Why do we bring this up, which is a very valid cause, but only helps a small number of people? A special controller like this may be making games accessible to only a few people across the world.

Chimowitz: It’s not just those players that have the chance to play games, though, and never could before. It’s their families that can now see them happy and engage with them. It’s a multiplier there. I’ve also met people like the founder of Nevermind. She created a game to help patients with anxiety and PTSD using biofeedback, measuring your heart rate through an Apple Watch, using facial recognition through a webcam, trying to train them to calm themselves. We have all this technology to play with, and eventually it can lead to something fantastic.

GamesBeat: I went up to Redmond recently and visited Microsoft’s inclusivity lab up there. They’re working on research around different ways to control games. One of the interesting a-ha moments around this — if you work on technology to improve games for a few people, you may find things that actually benefit everyone.

Who’s to say that a 16-button controller that’s been that way for decades is the best way to interface with a game? It actually creates a lot of obstacles for people who are intimidated by that barrier to entry. Nintendo abandoned that thinking when they created a Wii, creating a controller that recognized gestures. The research that goes into finding alternative ways to make games accessible can come back in a big way to help millions of people.

You can think back to the space race as an analogy. NASA created a way to land a man on the moon, but we got all these other benefits from the technology that resulted, including semiconductor chips, and even things like Velcro and Tang. All of these unintended consequences come out of research into technology that in some ways may help just a few people.

Levin: I still think, forensically, we haven’t discovered the value of Twitch in terms of expanding the global games audience. Even though it was bought for a billion dollars by Amazon, when you look at the markets it was able to couple together — so much of that traffic was coming from eastern Europe and China and Brazil, markets where there wasn’t console penetration. You were dealing with these massive audiences that now have the ability to participate in the global games community in a way they hadn’t before, or to a much lesser degree. Companies like Gamespy did that early on, with its middleware game crawler, but this was the first global-scaled platform, ESPN for esports, if you will.

Most folks would recognize that was a steal at a billion dollars. What it was able to do in terms of the direct connection between consuming constitutencies, we’d never seen that before.

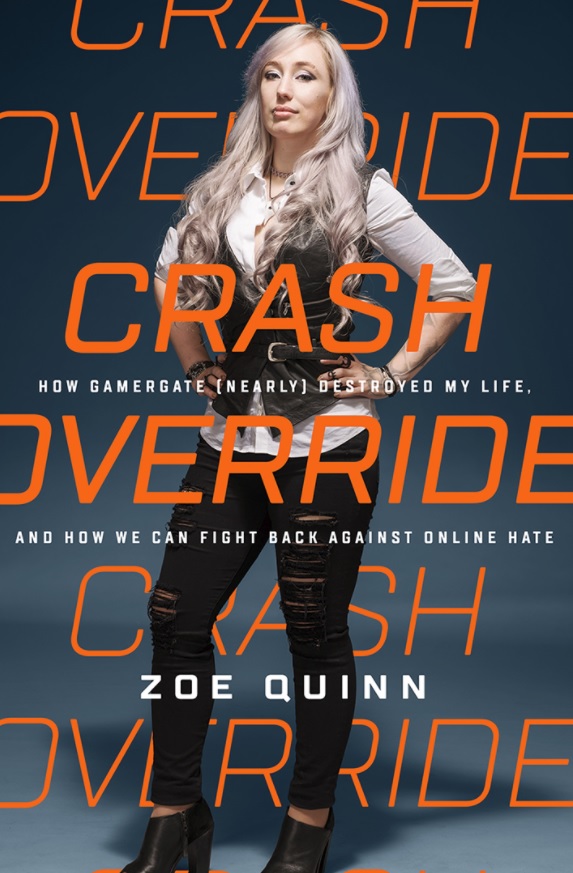

GamesBeat: We can think of some things that have held gaming back in some ways. There’s the mass culture on one hand and the subculture on the other. I wanted to talk about this a little. Toxicity in the subculture of hardcore games is something that’s scared people. You look at Gamergate. You look at how the internet has been used to bully people who aren’t good at games, myself included. This gets a little scary. It intimidates people. It stops them from picking up a controller to try out a game, because in some ways gaming is perceived as not welcoming.

Greer: I don’t see this as a toxicity problem in games so much as a toxicity problem in online culture generally. Games, because so much of what happens is online, and is so much about group play and group interaction, which is amazing, also attract that general online toxicity.

What I think is interesting and special about games is that we have a unique opportunity to try to progress and reshape the culture of toxicity. A large group of publishers in the last year announced a group called the Fair Play Alliance, which includes a lot of people like Riot and Epic as well as smaller companies like Kongregate, where we’re sharing data and best practices with each other as we experiment with incentives and forms of communication and feedback mechanisms in games that encourage positive teamwork, as opposed to negative griefing.

That type of effort can create a lot of learning in the game industry that can hopefully go on to be useful for companies like Facebook and Twitter in the general culture. I also think, in games, we have a little more freedom to experiment. Everyone is there to play games. There are fewer questions around freedom of speech or what right a platform has to tell you what to do. We’re here to play games, for everybody to play games.

Above: Dean Takahashi (left), Peter Levin, and Frank Soqui at games going mainstream panel at Milken Institute.

Soqui: I’m a fan of the Fair Play Association as well. Intel is a part of it. I want to amplify part of what you said a bit, which is — whether you like it or not, this toxic environment exists socially. People on different sides, in different audiences — I don’t know if you want to talk about politics, but it’s just very toxic. And it doesn’t have to be.

The thing that gives me hope about some of the online things going on, including gaming and other social media — although the ability to be toxic seems to become easier, the community that comes out in response to that, it’s also easier for them. I don’t want to say we can fix the world’s problems, but people need to lean in. If you stand for something as a gamer, if you want to include everybody, including people who have physical disabilities that might prevent them from being there—if you want to be inclusive, if you speak out on what’s going on in the gaming environment, most people are going to join you.

I think there are tools and things we can put in place. Some of the research from groups like the Fair Play Association might reveal some things. But ultimately toxicity comes down to, what do you believe and want to be known for? We have to be able to speak out as gamers and people who support gaming to say, “This is wrong. We’re here to have fun and connect with each other.”

Above: Zoe Quinn’s book Crash Override chronicles her Gamergate experience and how she is fighting back.

GamesBeat: At another panel I heard an interesting thought, which is that toxicity is associated with anonymity. More and more, gamers and the communications systems that support gaming, are heading toward live communication, live interaction. If you’re a streamer and you’re a toxic person, if you use that kind of language in your stream, you get called out and asked to apologize by lots of people. It removes some of that anonymity from how you behave.

Hopefully we’re not scaring all the investors out of the room here. They’re scared of games already, in a way. We’ve always heard a phrase about investors fearing games because it’s a hit-driven business. They’ve shied away from trying to pick hits, the same way they’d shy away from trying to pick which Hollywood movie is going to be a breakout hit.

But in some ways — I know another investor, Jon Goldman, who invests only in games. The way he puts it, this is true of any investment. If you analyze any business, there’s only going to be one Amazon. There’s only going to be one Google. You take risks by investing. Gaming doesn’t have a double handicap in this way. You just have to pay attention and realize you may be taking a risk. I wonder if any of you have thoughts on this phenomenon.

Greer: Yes, it’s hit-driven, but those hits are really long-lasting. A successful game will last not just for months or a year, but for decades. We see that with World of Warcraft, Pokemon, Candy Crush. Almost any major game you can name has lasted and remained tremendously popular for years. Yes, you’re investing toward that one special game, but once you have a hit, you’ve created a profitable cultural phenomenon that can have really long-lasting value.

Levin: Part of the issue is, you have a culture and a DNA in a lot of the investment communities where they don’t have a track record or experience investing in anything content-related. The notion that a games investment would somehow differ from investing in a production company or a digital studio or a VR production entity—some of it is the shiny toy phenomenon. “Let’s invest in that that thing that’s getting a lot of attention.” Then it becomes part of their portfolio. It’s neither fish nor fowl, and inevitably, as companies do, perhaps they miss their number or miss a milestone or the market slows down. Then a lot of questions get asked around it.

The good thing is, as the games business has diversified and matured, you now have a group of investors who bring that pedigree and acumen and network and operational experience to the table. We have a bunch of those partners in deals we do: VCs like Ridge Ventures, Phil Sanderson there, or Gregory Milken, who’s a partner in at least two of our deals. Mitch Lasky. Index. The list goes on. You’re starting to get VCs that have multiple people within their portfolio of investors who bring in that perspective and experience. They better understand—to the point that was made, it’s the worst acronym ever, but GAAS, games as a service.

It rings true, because when you look at the number of titles that have now existed for five, seven, nine, or 25 years—Maple Story is a great example. It’s so far beneath the radar screen, but what an unbelievable story. That speaks volumes.

Above: Mobile gaming is half the global market.

GamesBeat: There are other investment strategies as well. There’s the picks-and-shovels strategy, or going up a level and abstracting to the platform level. Someone who’s shy about investing in a game might be more inclined to invest in a game platform. A lot of startups in the game industry have recognized this and pitched themselves as game platforms or toolmakers instead of makers of individual games.

Greer: We’ve also seen some interesting innovation from things like Kickstarter, where essentially the funding and investment for games is coming from gamers themselves. It shows there are maybe opportunities for investment from people who are already passionate.

Soqui: It comes down to why you’re investing. Not all investors are built the same. Some are looking for disruptive technology investing, because they’ll bet on 10 and one will win. Some are looking for steady, flat growth because they want to take risk out of their portfolio. Some of them have a diverse portfolio, where they’ll invest in infrastructure, invest in distribution mechanisms, and invest in a game itself. When you say investors are shy because it’s based on big hits—if that’s the type of investing you’re doing, you’re probably investing in the wrong thing, if you’re only focused on big hits. It sounds like you’re looking for just one win to make your portfolio.

Nothing else is like that. If you invest in real sports, it’s not like that — if you invest in advertising, distribution, leagues, merch, you name it. What do you invest in? What kind of portfolio investment are you? What are you looking for?

Levin: I do think esports has taken a page somewhat from what not to do. There’s a lot of dumb money being thrown at a bunch of team ownerships and being a foundational block in the standing up of some of these leagues. When you look at, for example, the quality of ownership that’s been put together around the Overwatch League, it’s a breath of fresh air. They went through an arduous process of filtering and editing and making sure they were making decisions based on strategic value, operational expertise, market acumen, all of these things.

You now have folks sitting around this table where there’s plenty of gaming DNA, global sports infrastructure operational DNA, licensing and merchandising DNA. These are areas game companies never played in before: apparel, shoe deals. All of these worlds that no one ever thought would collide are colliding. You want them to collide with the folks who have the acumen to act against that.

Some of the other publishers have just plucked folks from game operations, from that side of the house, and said, “Hey, now you’re going to run our league.” You wouldn’t do that in any other business. I’m not gonna go out and run a waste management company. There’s a learning curve. Maybe I could figure it out over time, but I would be a liability.

Esports, yes, we’ve talked about like it’s the shiny new toy. In the last couple of years VR was in that role. But I think it’s wildly different. The contemplative nature with which a lot of these folks are vetting their ownership speaks to that.

GamesBeat: We’ve touched on this notion that investors might be more interested in investing in something like games, plus something else. Something on the edge of the game industry. I brought up blockchain and cryptocurrency in games, but nobody on the panel wanted to talk about that. It’s a whole subject unto itself.

I’m one of those gamers who would like to see the metaverse happen. That’s a collection of worlds. It’s not just one worlds, but several virtual worlds. The way you would connect those worlds is through a cross-platform technology, and the transparency of blockchain, to me, seems like a necessary tool for that to happen. Tim Sweeney, the CEO of Epic Games, thinks that blockchain is one of those building blocks for the metaverse, and he thinks it will be buildable in a short period of time.

Soqui: I would say that blockchain is probably a contributing factor, but let me hypothesize something else, which is that if you want individuals to be part of this metaverse, and you want them to be able to create their own version of the metaverse as an add-on, and you want to democratize these things, I think distributed compute — being able to control my environment and hook it in to other environments — that whole backbone of infrastructure is what’s going to enable that to happen. Transactions and IP can be secured with blockchain, but fundamentally, you need a software and hardware architecture for something like that to happen.

Above: Ready Player One

GamesBeat: Blockchain is decentralized, of course, and that’s another interesting subject within games. I’m curious what you think about the forces that are democratizing and decentralizing the game industry, versus the forces that monopolize and centralize the game industry.

Soqui: Democratization is an extension of a shared economy. That’s a fundamental belief. When I make it easy for someone to do something with an asset that they have or they want to control, you get disruptive advancements. You get people doing what they want to go and do. There are companies emerging today that are starting to democratize what’s going on there.

It’s an intersection between some of the big players and some of the small players that are trying to democratize the development of games and the social interaction around games. Whether one wins or not, it’s just business economics. Once something becomes apparent that it’s democratized, like Samsar democratizing VR and the creation of VR content environments, someone’s going to want to invest in it. VCs will want to get in on that.

Things like that are happening. I don’t think it’s winner-take-all. I’m glad there’s democratization because that increases the total available market. Individuals can participate in an economy rather than just buying services in that economy.

Greer: The key to democratization in the game industry in the last 15 years has been the creation of tools, professional tools like Unity and AWS, that make it possible for very small teams, anywhere in the world, to teach themselves how to make games and then go and make them. As a publisher, we work with a lot of very small teams that make games. Sometimes as small as one or two people, who are making games that we take to the mobile app stores and see 10 million or 15 million installs.

AdVenture Capitalist is one example. It was made by one person in 30 days as an experiment, a learning process, and now it’s a multi-year success. That’s a tremendous democratization force. It doesn’t matter that Electronic Arts has some amazing engine they work with, or Epic or anyone else. It’s allowed games to be made by anybody, anywhere in the world.

The enormous counter to that is that with so many games coming out, it’s difficult for any one game to get attention. It used to be difficult to get on store shelves at GameStop. Now it’s difficult to get the attention you need on the app stores, on Steam and so on. What we’re finding is that the anti-democratization force is the need for advertising to reach any kind of scale. Advertising needs a big budget. Very small teams can make games, but it takes a very large budget to get those games in front of people. That’s a counterforce in the industry.

We have new phenomena like YouTubers and Twitch streamers who can discover some amazing new game and start talking about it. That’s another democratization, in advertising and promoting games. But it’s often out of your control. Maybe you get attention and maybe you don’t. It’s frustrating for a lot of creators to have so many things still out of their control.

Soqui: I don’t think the goal of democratization is always scale, though. We talked about Roblox recently. The person who made that was just doing something for himself and his friends. It just happened to take off. Sometimes the goal behind democratization is just satisfying a need that happens to be unmet, not because you’re trying to get to a major scale. Bigger companies will look at those ideas and find out what might work as far as taking them to scale. It’s a continuum, a segmentation model, as opposed to just one person takes all.

Levin: As a capitalist I would say we’re trying to get to a place of viability. It’s great that you see these one-off stories of one or two people who created a curiosity and it took off. But there’s a bunch of different third-party publishing models that are developing and evolving. You’re dealing with massive markets that have been untapped, that monetize differently than other markets. I’ll focus on India again. Their in-game monetization behavior does not mirror that of the west or that of China. That’s going to evolve into its own thing. Looking at game mechanics, you have games that have risen so far above the norm, like Fortnite, that pale in comparison to the marketing budgets of some of the biggest publishers in the world.

Above: Fortnite

GamesBeat: An interesting factor there is that the battle royale genre didn’t arise from a budget like Call of Duty or Battlefield. It was essentially one guy.

Levin: You look at that, maybe it’s because of the nimble nature of that company. They have a platform play as well, similar to Unity. You have all these mutually aligned interests, and that’s helping to create these new relationships between bigger players and smaller players, where their interests are financially aligned.

GamesBeat: It seems to be like a tug of war between the centralized side and the decentralized side, and the decentralized side is winning at this point. In that tug of war there are lots of opportunities. Before mobile, the game industry was Europe, Japan, and the U.S., and in the U.S. it was mostly on the west coast. With mobile, it’s half the business worldwide now, these companies can be started anywhere, and they have arisen everywhere.

I’ve written about game studios in Siberia. Supercell is in Helsinki. They’ve democratized jobs in the game industry in a huge way. They’re now spread across many nations. Jobs can be created in almost any country now. Eventually, a centralizing force comes along, and sometimes it ties all those things together. In particular, I’m thinking of the largest game company in the world, which is Tencent. Tencent owns a piece of Activision and a piece of Epic Games. It owns Riot and Supercell. It has a huge business in China. But it’s always been investing as a minority. It hasn’t taken over and consolidated as many businesses. It’s an interesting tug of war in itself, between centralization and decentralization.

The outlook for games is very positive in a lot of ways. Many forces are pushing and pulling it in different directions, but it seems like the outcome can only be good. Do you have any closing comments along those lines?

Soqui: Sometimes we ask questions like, how big is the gaming market? How many people are playing games, and in what demographics? Everyone’s a gamer. Whether you’ve played cards or board games, it just goes from there through more and more that’s been enabled now online, in digital media, in content creation, everything we’ve talked about today. If you ask yourself, “Am I a gamer?” Yes, you are. Everyone is already a gamer. It’s how we interact with each other, how we socialize, how we compete in ways that are fun. It’s just being taken to another level.

Remember that. Gaming is not a new phenomenon. It’s just exploding across all these different boundaries. The reach and the way it pulls people together is something that hasn’t happened before.

Chimowitz: There’s a new platform called Kahoot that allows anyone to make a game, to make a quiz game. Educators are using that to teach kids math and science. You can use it as tool for testing and training new hires in an easy way. Gaming is everywhere — in education, in the workplace, at home.

Greer: The thing to keep in mind is how many hours per day people spend playing games, in terms of — if you look at the engagement with games, so many of them have not just hundreds of thousands, but millions or tens of millions of daily players putting in an hour or two or three. It’s shaping the world we live in in a very meaningful way.

Levin: It’s also pulling in — look at how much has been said about teenagers. “How do you parent through Fortnite?” You can’t turn on anything these days and not have someone trying to educate you about how to literally parent through gaming. But there’s also been a lot of upside and positivity that’s been discussed around it from those who study sociological dynamics. A lot of kids are pulling from multiple constituencies in their lives that they never would have put in a room together. They’re cooperating in a way that they never have before.

Yes, it is rife with all the things that transpire in any online environment with social dynamics in and around it. You throw in anonymity and then you really get the cowards to rear their heads. But with that being said, folks are working toward a lot of transparency. The great thing is, to your point about the metrics of consumption, that cannot be ignored. The price points of game products cannot be ignored. The sheer scale of the industry versus other forms of media cannot be ignored. Everything is tracking in the right direction.

Above: Left to right: Kathee Chimowitz of BoomBit Games, Emily Greer of Kongregate, Dean Takahashi of VentureBeat, Peter Levin of Lionsgate, and Frank Soqui of Intel.

Audience: I have a small telecom license in India, and what I’ve found there is that the younger people, compared to people my age, are now beginning to explore the game industry. I’ve also visited several countries in Africa, and I’m trying to find out how we can bring this business on to a continent where it can give young people a new source of entertainment, compared to legacy media.

Levin: I can tell you, in the two big markets, Middle East and North Africa, there hasn’t been a strategic conversation we’ve had in the game space where that is not a focus. I do think it speaks to one of these untapped markets. It feels as if there’s a tremendous appetite. I know Saudi, for example, punches way above their weight for Overwatch consumption. It’s a crazy number.

GamesBeat: There’s a new VC firm called Altered Ventures whose mission is to invest in emerging markets and game projects. That’s one encouraging sign. Another is, to have good game developers and a good game industry in your country, you need gamers. That’s where you start, creating a nation of gamers. Good games follow.

Audience: Last year, Metacritic released a list of top game publishers. Of the five most successful last year, none of them had a new IP. Can you talk about existing IP and using that to cut through the market, versus independent darlings who are releasing new IP?

Levin: Half of me wants to say it’s great that they don’t need new IP. It’s no longer about shrink wrap and shelf life, where your game has six weeks on the shelf and then they throw it in the discount bin. That model has completely changed. All that friction no longer exists. That’s a really positive thing. The flip side is that new IP get introduced all the time. We didn’t know what Fortnite was three months ago, or most folks didn’t. You can read data that probably makes a case either way, but stepping back, there’s a solution.

Soqui: It sounds like you may be referring to IP in the context of an application. My IP is my name. But there are different kinds of IP within that IP that invites audience participation or viewership. There’s IP that exists in the silicon layer. There may not be brand new games on the horizon, but don’t discount the indie developers out there. They’re helping expand the market, and the guys that don’t have new IP are watching.

Greer: It takes a while for something to grow into a top IP, too. Sometimes it happens in a month, but often it can happen over a year or more, a slower build. Today’s new IP is next year’s top five franchise, or two years from now. That speaks to that depth of engagement, the length of time people spend playing games and how that can build slowly over time.

Disclosure: The Milken Institute paid for my accommodations at the Milken Global conference. Our coverage remains objective.