Above: Margaret Wallace, CEO of Playmatics, talks about the future of A.I. in game design.

GamesBeat: That’s an interesting direction for things to go. It brings in this idea of A.I. for promotion and marketing. Kabir, when you hear about something like that — you could have the bartender answer some questions in a way that promotes monetization or retention. From your point of view, on this side, can you talk about the potential of what A.I. can do?

Mathur: Having the bartender say something specific is out of the scope of what an ad network can potentially do. But there are a lot of analytics tools and out-of-the-box tools that allow for personalization. What we’ve noticed, working with thousands of game developers, is that everyone is trying to funnel all their users through the same experience. This is very similar to the way ad networks think about user funneling. You’re trying to get a user from point A to point B as efficiently as possible and get as many of them as you can through the funnel, which is similar to how a game works. You have a tutorial and you have levels, and you want as many users as possible to go through that process, hopefully making a purchase along the way.

What we recommend—we work with these personalization technologies and deploy them with several different variations of content to appeal to different segments of users. The ultimate objective is to have an experience that’s tailored down to the individual user level. Andrew Wilson at Electronic Arts just spoke about something very similar a month ago, where he said that they want to move into user-based narratives. Every user will have their own narrative and you’ll never have to play the same thing twice.

That’s a pipe dream for most developers, perhaps, because they just don’t have the budgets, but these out-of-the-box technologies I’m referring to will, in combination with things like Facebook Connect, know enough about a user to where you can say, “This user is from this location. This is their approximate age range. This is their gender. I know I can deploy this type of content for them, and it might be more effective than this other type of content that might work better for, say, a woman aged 35, as opposed to a man aged 18.” You can deploy five or 10 different experiences, A/B test against different segments, and choose which ones to deploy to which user, the best available that you can predict.

Fletcher: One of the things my company is trying to do is to bring that specific user personalization to any mobile developer. The reason you see EA doing that now, or Amazon, is because they have the data. But there’s this idea about the unreasonable effectiveness of data in A.I., getting enough data to be able to make decisions. We want to provide developers a solution where we have all that data, and once we have that data it’s actually the same techniques you would use for segmenting. You can just apply them on a per-user basis. You get to say things like—if I’ve watched this player go through these events, maybe thousands or tens of thousands of events, that can then trigger the bartender to say, “Hey, I happen to be dating the blacksmith’s son, if you buy these gems I can get you a discount.” It becomes an integrated IAP prompt.

What we’re working on is the control points in that process. “Trigger the IAP prompt now. This is the time when this person is receptive to that.” And that’s by watching all of that data stream come in and saying, “Trust the machine to figure that out.” That’s the approach we’re taking to bringing in that level of personalization.

Above: Richard Bartle of the University of Essex hypothesized about why people quit games.

GamesBeat: A.I. helps us feel that a game is personalized in some way. That’s both on the marketing side, where the game is trying to sell us something, and on the gameplay or narrative sides, where the game is just trying to keep us engaged and playing along in a way that feels natural and enjoyable. But it seems like there’s a problem with personalization.

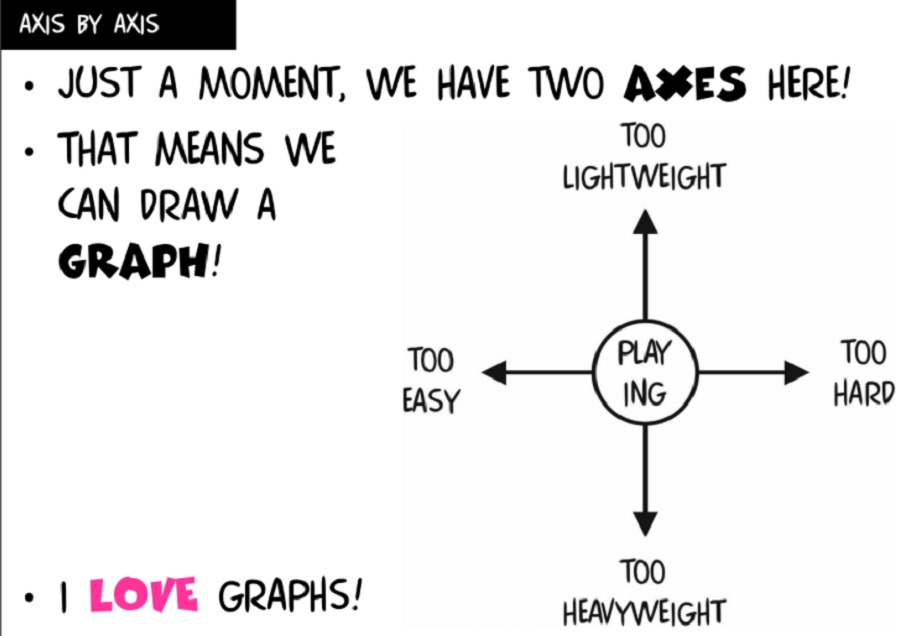

Richard Bartle, a well-known professor who’s studied games, gave a talk recently in Barcelona at the Game Lab event talking about how the problem is that every gamer is different. If you’re trying to design a game’s A.I. so that it isn’t too easy to play against, nor too hard, that’s important for retention, but you never know where the line between too easy and too hard really is. How do you guys think about that problem?

Wallace: I think about that a lot in the context of game design, just trying to differentiate a bit from the rest of this discussion as far as our focus. At Playmatics, we’re a small startup. We work with all kinds of folks with different capacities and resources. We all know where we want to go with things like A.I. and machine learning, and sometimes we can go there depending on what we have to work with, but sometimes we can’t. Just because you have the ability to leverage A.I. or machine learning in a game experience doesn’t necessarily work out on a pure one-to-one transactional basis. It could actually be a demotivational experience.

For example, I’m working on a project right now involving A.I. in a scavenger-hunt mechanic. It’s an app that already exists. My first experience with the app, beyond the registration, was discovering that the A.I. has context-sensitive mapping to tell me what objects are near me, but the first object it served up was so incredibly rare that finding it would be an impossible task right out of the gate. It was very demotivating for me, even as someone who was very motivated to engage with the app at the start.

That speaks to things like personalization – understanding player style and practices. It speaks to issues of onboarding, and making sure that if you’re going to apply an A.I. mechanism to an experience, you really need to test it out with different use cases. How many of us have been served a memory on Facebook that you don’t want to be reminded of? That’s not a good user experience. To me that’s a prime example of A.I. going wrong, or algorithms not being tested out for everyone’s use case.

Wirtz: There’s a thing in storytelling that also applies to gameplay, called the storyteller’s curve. If you watch Star Wars, it opens with this big, exciting scene, very high drama, and then it settles down so you can rest for a while and have a contrast with more drama later on. If you’re in a driving game and racing Laguna Seca, it works the same way: a straightaway into a curve, then it ramps up the excitement level. And then the A.I. in Left 4 Dead did this with its zombies. They’d say, “Oh, we’re going to herd you and chase you and then something will jump out of somewhere at the climax.” It builds up that big fright by making you run, and as soon as you think you might be safe, bang, all the zombies come out, because it’s monitoring what your controller is doing and all this other stuff.

That A.I. is driving the experience in a way that’s not necessarily personal to you, but it reacts to what you do in a way that feels personalized. Your health just dropped to 15 percent, so let’s give you a chance to catch back up so you don’t just die right away. You feel like you’re reaching achievements along this curve. That’s a big part of what A.I. in storytelling is doing right now.