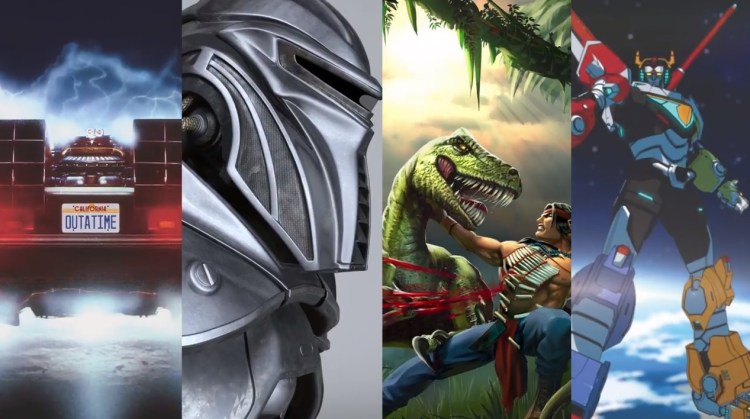

Above: Eat your heart out, Epcot.

Lokum: That’s a good point to make. There’s really no other medium where you can get in there for hundreds of hours and interact. At Universal we’re a story-driven company. It’s about content. What you’re doing is important content to us.

Games have grown up. I get multiple emails every week asking, “How can we work with Fortnite?” This is from executives all throughout the company. It’s top of mind. People think about games. This is a great time.

Gale: I’ll start this with one of my favorite quotes. “If you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans.” I grew up in St. Louis, Missouri. I learned to draw copying pictures out of Disney picture books. My ambition was to go to California and work for Walt Disney. When I got a little older, I started copying pictures out of DC comic books, and my ambition was to go to New York to work for DC and Marvel and Mad magazine.

Then I picked up a movie camera when I was in high school. I said, “This is cool. This is what I’ve gotta do.” I went to USC film school, managed to get myself in there. Much to my parents’ chagrin, because if you’re from St. Louis you don’t tell people you’re going to California and going to Hollywood. But they were cool enough to let me go to school out here. I met people who were as passionate about the movies as I was. It was where I met my partner Bob Zemeckis, and we decided to team up and start making movies together.

The story I most like to tell is that we wrote the script for Back to the Future in 1980 and 1981. We were hired by Columbia Pictures to write it, because we’d done our previous picture there. They rejected it and gave it back to us to try and set it up someplace else, because that way they could make their money back.

The screenplay for Back to the Future was rejected more than 40 times. Every studio in Hollywood rejected it at least twice. Producers rejected it left and right, for all different reasons. It was too nice, too sweet. We heard over and over, “Take it to Disney. It’s very sweet. Go to Disney.” Comedies like Porky’s and Stripes were the big movies at the time, raunchy movies. So we thought, “Maybe they’re right. Maybe this belongs at Disney.” This was the old Disney, before Michael Eisner took it over.

We took a meeting over there with an executive. We walked into his office and he said, “Are you guys out of your minds? You’d submit this movie to Disney? This is a movie about incest! You’ve got the kid and his mother in this car! We’re Disney! We don’t do stuff like this!” So we didn’t make it at Disney.

Above: Most of the contest entries came in for Back to the Future.

I tell this story because Bob Zemeckis and I never stopped believing in Back to the Future. George Bernard Shaw once said that a reasonable person adjusts his views and goals to fit the world. An unreasonable person tries to adjust the world to fit his goals. Or her goals. Therefore all progress depends on unreasonable people. Bob and I were two of the most fucking unreasonable people you could ever meet. Somehow we figured out how to make Back to the Future, and we did.

Not everybody can be the grand prize winner here. Out of — how many submissions do we have, 500? We all looked at 20 of them, and most of them were really good. You guys all floated to the top. More of you are going to get rejected. But that’s okay, because you learn from rejection. Just because you get rejected means that the judges know what the fuck we’re doing, because maybe we don’t. Or maybe there’s more than one game here that deserves to be made.

No matter what happens here, if you care, if you have the passion, if you really give a shit and you have that drive and insanity and ambition to keep on going, then keep on going. The world needs you. The world needs what you can do. The world needs what you can bring to it. The history of invention in technology is full of people that were laughed at and ridiculed and rejected for ideas that were thought to be stupid or crazy or just not practical, and we’re here.

If you’ve never read the book The Innovators, by Walter Isaacson, which is a fabulous book covering the history of the computer industry from Babbage all the way to Google, do yourself a favor and read that. It can be very inspirational to me, and it will be to you, to find out what all of these people that we consider to be the founders and the gods of this business, what they had to go through to get there. It’ll help you get up in the morning and keep fighting that fight.

Lokum: All of you guys are really winners right now. This is kind of a once in a lifetime experience. Take it in and, once again, we hope to help you in the next step of your career. To Bob’s point, you’ll make what you put into it. We want to encourage you and give you the tools to get back what you put into it.

Throughout your careers, if any of you had one mentor that gave you a piece of advice that really influenced you and helped you, what was that?

Above: Indie devs will have a chance to pitch a Back to the Future game.

Edwards: I’ve had direct mentors. Some of these were people I didn’t think of as mentors at the time, but in hindsight they absolutely were. They were my Obi-Wans and Yodas and whatever clichés you want to use. In the moment I didn’t realize that they were trying to correct me. One of the most powerful pieces of advice that one of them passed on to me was actually the wisdom of Mark Twain, where he said, “Comparison is the death of joy.”

I use that in a lot of lectures these days when I talk about advocacy. Comparison is the death of joy. One of the things I’ve dealt with myself, and a lot of people in the industry as well — we all deal with imposter syndrome. A lot of that is built on comparison to others. Artists who look at other work and think, “I’ll never be that good.” It’s one of the reasons why, when I give lectures about this, I’ll put up a slide with a Rembrandt portrait and a Picasso portrait and ask people to tell me which one is better. There’s no answer. The thoughtful person will realize that you have to just focus on what you can do best and don’t worry about being somebody else, or doing what somebody else is doing.

If you see someone around you who does something that you think is better than you, guess what? You may have found a mentor. Go ask them: “I’d love to learn how you did that.” If they don’t want to teach you, that’s their issue. Go find somebody else who can. Keeping your focus on exactly what you’re capable of doing and what you want to do, rather than comparing to everyone else around you — I know that for me, that was extremely powerful advice.

Part of the reason I stuck with a career that’s been so bizarre, with all these different paths — conventional wisdom would have asked why the hell a geographer is working at Microsoft. Why is a geographer working in video games? Because I wanted to. I didn’t want to compare myself to what other geographers were doing. I set my own path and I’d encourage you to do the same.

Montgomery: Unfortunately my story is very personal, and really only applies to me, but I’ll tell it to you anyway. [laughs] It ties to what I mentioned before. I was working on shows about boys for boys, and occasionally being able to get a woman character in there. I had a friend, a producer, come in one day and he said to me, “My wife reads a lot of manga.” Manga, as you know, covers every subject. There’s manga about tennis players, a manga about baking a specific kind of muffin. It’s every weird little niche. His wife was really into certain manga series because they appealed to her.

He said to me, “Lauren, you’re in a position where you can effect change. You can make things for women.” I’d always known I wanted to work on content that included women more, but I don’t think it was until that moment that I realized how I needed to not just accept that was given to me and I needed to push harder for it.

That was a turning point, purely for me. I don’t know if it applies to you guys. But maybe at some point in your career you’ll have someone who comes to you and says something that snaps things into sharp focus. Maybe you’ll find yourself in a position of power where you can push for those causes that you really believe in. That’s my story.

Above: Turok: Legacy of Stone

Gale: I had really two mentors. A writer-director, John Milius, and Steven Spielberg. It’s really very simple. Bob Zemeckis and I had written a script. Milius was a legendary graduate of USC film school. If you don’t know who he is, his most well-known works — he wrote Apocalypse Now. He was the writer-director of The Wind and the Lion, with Sean Connery and Candice Bergen. He wrote and directed the infamous Red Dawn. There’s a great Netflix documentary called Milius about him, that really encapsulates what filmmaking was in the 1970s. He also wrote the famous Robert Shaw speech in Jaws about the USS Indianapolis.

Anyway, Zemeckis and I gave Milius a script we’d written on spec. That means we wrote it ourselves, without getting paid for it. John read it, he liked it, and he hired us. That’s the best thing that can ever happen. A professional likes your work so much that they encourage you to continue. Hiring you to write a script, in my business, at that time was the greatest thing that could happen to you.

Milius was good friends with Spielberg, so Spielberg came to read some of our work. He said, “Jeez, you guys can write. You’re talented. Make a movie for me.” It was that simple. We found people that liked our work so much that they were willing to hire us.

Takahashi: I’m a journalist, and my job is fun because I get to talk to a lot of people. I talk to people who might be enemies of each other — one person might be on one side of the story and another person might be on the other side of the story. What I’ve always liked about that is how people surprise me. They always do something or say something that I didn’t expect. I try to keep talking to people until I find something like that.

One reason I do that goes back to my father. He was a strict Asian dad in a traditional Asian household. The paramount thing was to get good grades in school. I was going down the track of being an engineer or a doctor or something like that, until I got a C in calculus and a C in physics. This was a disaster, especially because I had an older brother who aced all of these things.

When it came time for me to go to college–my brother went down the traditional route, but he struggled with it. He eventually found something different. When it was my turn to go to college, I was kind of dreading what my dad would actually say about this. I fulfilled all the requirements for business school, and I tried to take some science and math in college as well, but I was drawn more to writing. I’d always wanted to be an English major and write.

I told my dad, “This is what I’m going to do. Journalism is fun. English as a major is what I want to do.” He was very supportive, in the end. He surprised me. It was because, when he was young, he had no choice but to do something really practical. He became an accountant. What he had really wanted to do was study history, be a history teacher, and he’d always regretted not going where his passion was. So for me, he told me, “Do what you want.” That was good advice.

Lokum: We have some great storytellers on the panel. As I mentioned before, you’re all storytellers in your own right. You’re extending the fiction of these properties for game. I’d love to hear from you guys what you think makes for a successful piece of entertainment, whether it’s a video game, or another kind of new technology. We know from Bob that picking cherries off of trees doesn’t do it. But what’s your opinion of the space today and what makes storytelling — whether it’s TV or movies or games — compelling to you?