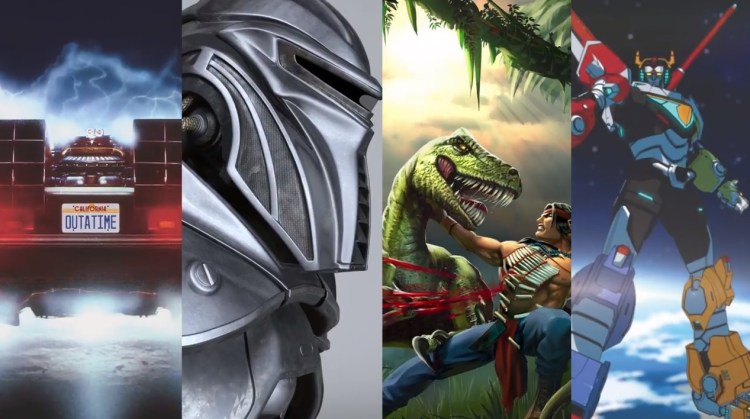

NBCUniversal, Intel, Microsoft, and Unity are engaged in a developer contest dubbed the Universal GameDev Challenge, in which the companies asked indie game developers to propose games based on its brands such as Back to the Future, Jaws, Battlestar Galactica, Voltron Legendary Defender, and Turok.

More than 500 indie game developers submitted entries in the contest, which carries a $250,000 prize and a rare chance for an indie to make a game based on a Universal license. I was one of the judges, and it gave me an inside look at how a big entertainment company can work with small developers on licensed titles. We chose six finalists, and the companies offered them professional coaching. The finalists are now competing to create finished games in the coming weeks. The final winner will be revealed at Unite LA on October 23.

During Universal’s mentorship event, I sat on a panel with my fellow judges, offering advice for the developers. Gary Lokum, the vice president of business development, games, and digital platforms at Universal, moderated the panel.

Besides me, the panelists included the other judges for the contest: Bob Gale, an Oscar-nominated screenwriter-producer-director, best known as co-creator, co-writer and co-producer of the Back to the Future films; Kate Edwards, CEO and principal consultant at Geogrify, the executive director of Take This and former executive director of the International Game Developers Association (IGDA); and Lauren Montgomery, co-executive producer at DreamWorks TV and showrunner for DreamWorks’ Voltron: Legendary Defender.

Here’s an edited transcript of our panel. I’ve also embedded a video from Universal about the contest and further advice from the judges on how to develop a sense of passion for games and figure out the kind of games they want to make.

Above: Universal GameDev contest judges (left to right): Dean Takahashi, Kate Edwards, Lauren Montgomery, and Bob Gale.

Gary Lokum: I’d love to know what you felt was intriguing about this program, what compelled you to participate? Bob, when we were talking early on, Back to the Future was something that we looked at. This is a property that’s beloved, that we want to do a great game with. I had to reach out to different creators to get them involved in this program.

I remember calling Bob and saying, “There are these new events happening. They’re called game jams. I don’t know if you’ve heard of them? People create games over the weekend. I’d like to get Back to the Future.” I had about 10 minutes of ammunition about why this made sense, and before I did any of that, he said, “That’s great! Let’s get it done!” That’s it. Bob, why did you think it was such a great opportunity?

Bob Gale: I’ve been playing video games since Pong. That’s how old I am. I’ve loved them ever since. And Back to the Future has spawned some of the shittiest games ever made. If you’ve never seen the YouTube video of the Angry Nintendo Nerd reviewing the LJN Back to the Future 8-bit Nintendo cartridge, put that on your must-view list. That was one of the worst games ever made. It was so bad that when it came out, I did interviews and told our fans not to buy it.

We go off to make the sequels and the game guys at Universal say, “We’re gonna do a license for the sequels.” I said, “Well, let’s not do what we did with LJN.” LJN was wholly owned by Universal, so we were stuck with them at first. They put this up for sale and Acclaim picked up the license. I think, “OK, Acclaim, they’ve done some good stuff. I’d love to have some input.” The guys at Acclaim were like, “Gale, what the fuck does he know? You’re a movie guy. We’re in the game business. Fuck you.” Okay?

And what did they bring? Well, it turned out that they didn’t have enough time or enough money to do it right, so they said, “We’ve got this subcontractor in New Zealand. They’ve got this platform game. We just have to change the images and the iconography to Back to the Future and it’ll be Back to the Future II.” They show me this game where Marty McFly is running around and jumping and grabbing cherries off trees. What the fuck is this? Back then there were two states that a game was ever in. Either it was too soon to tell, or too late to change. It was too late to change at this point. Again, I told people, “Don’t buy this piece of shit.”

It wasn’t until 2010 that we had a decent Back to the Future, thanks to Gary and the Universal guys and Telltale Games. When he told me about this, I said, “Okay, this is right. This is what we need to do. Let’s get the IP out there to people who love the movie. Let’s get all this IP out there to people who love Battlestar Galactica or Turok or Jaws or Voltron.” That passion is going to drive something much more exciting than you’d normally get when Universal just sells a game license to such-and-such company and you get a team of creators doing it because it’s their job.

Thank you all for entering this contest. Thank you for the love of these IPs, whatever you picked out, because this is how we can make exciting, great games based on this kind of material.

Kate Edwards: I’m involved in a lot of contests, judging a lot of contests, whether it’s indie game contests or larger events, all that stuff. I’m very familiar with judging games. But you almost never get to judge something you’re so familiar with. Going into a contest like this, where I’m vastly familiar with all of these IPs — some more than others, but I’m intimately familiar with the details behind them. I was instantly intrigued to be involved, because I wanted to see how the vision as it’s expressed in TV or film could be represented in games.

That was one of the biggest draws for me, other than I just like to judge. [laughs] But not in a bad way! I like to be constructive. That was what set it apart from a lot of other contests.

Lauren Montgomery: I have no involvement in video games, other than I am a gamer. I enjoy video games very much, but I come more from the TV and animation side of things. One thing I do know about is taking a beloved IP and creating new content based on it. That’s really exciting to me. I’m a fan of a lot of things, and sometimes I’ll just fantasize — how would I update that for today? How would I make that new?

That’s one of the things that was exciting to me about this contest, just seeing how all these creative minds were going to take these beloved properties and not only do something new with them, but take them into a new medium — take them away from television and into video games. That’s what excited me about it.

Above: Paul Saffo

Dean Takahashi: I come from Silicon Valley. There’s a futurist there named Paul Saffo. He always talked about this shift going on, economically, from an industrial economy to a consumer economy, and then to what he believes we’re all in now, the creator economy. I like to run with that and pose this idea of a leisure economy, where someday we’re all going to get paid to play games, to be entertained.

I’m an example of that. I’m a game reviewer. But all kinds of people are getting paid to play games — esports competitors, modders, live streamer, YouTubers. This whole set of people have created jobs that have never existed before. This contest was interesting to me because it’s making more of this happen. Indie developers, people who aren’t so different from modders — perhaps a professional level above that — getting together with all this cool IP and seeing what comes out of it. We all know that fan-fiction can be pretty cool stuff these days. This seems something like that. It was pretty interesting.

Lokum: One thing that I got when I was talking with different developers is that we have lots of different experience levels, people at different stages of their careers. But one thing I heard that really spoke to me — some people are doing this as a side job, but if it actually works out for them, they could quit their job and do this full time and really follow their passion.

One of the questions we had was, all of you are very successful now, but you didn’t just arrive there. You worked to get there. Whatever type of adversity you might have gone through to get to this point in your career — I’ll start with you, Kate, because you have a very interesting background. I also think you’re a kind of pioneer when it comes to diversity and sensitivity in the game space. What type of adversity have you run into? What made you stronger to get to the point you’re at now?

Edwards: To put it briefly, when I went to high school, I wanted to be an astronaut. I was four years old when we stepped on the moon, and I’ll never forget it. I wanted to do that. That’s what I aspired to do. A year of calculus and aerospace engineering at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo nearly killed me, so I changed my major to industrial design and went to Cal State Long Beach, because I knew most of the artists at Lucasfilm had an industrial design background. I wanted to be an artist on Star Wars. I had the artistic skills, and I wanted to be able to draw like them.

But I got bored with that program, so I changed my major to geography and cartography, because I loved maps. I loved culture and travel. I could still use my artistic skill with cartography. I never lost my love of space, of Star Wars and geeky stuff, but I decided to go in a different direction. I ended up staying with that, and got my master’s degree in geography. I did a master’s thesis in 1991 about AR and VR for cartography.

Then I got pulled into Microsoft. I thought it was going to be a three-month contract to work on the Encarta encyclopedia, and I ended up staying there for 13 years. While I was there, I noticed a huge hole in the risk exposure of the company, where they weren’t addressing the cultural and geopolitical implications of the content in their products. Things like flag usage, gesture usage, the maps in their games. Once their games division got started, things like character design and all these other factors that can get you in trouble in different cultures and with different governments depending on local expectations.

Above: Kate Edwards is CEO of Geogrify and a board member at Take This.

With my background, I wrote up a proposal to create an internal team called Geopolitical Strategy. It took nine months of persistence and talking to different VPs to finally get one to approve it. It was the one who was not from the United States. He instantly got it. [laughs] And the rest was history. I led that group until 2005, when I became a consultant.

My love of games took me here. Like Bob, Pong was my first game. That’s how old I am too. I’ve loved games ever since. I never aspired to work in the game industry, because honestly, when I was young, there wasn’t a lot to be said for the existing game industry. There were no game design degrees. But I just went down this circuitous route, following my passion, doing what I like to do.

One of the footnotes to this is that, many years later, I actually got to work on Star Wars: The Old Republic for four years. I got to work on Star Wars as a culturalization consultant, not as a conceptual artist, but I still got to do it. The circle was complete. It’s a lot of persistence, a lot of following a direction that made no sense at the time.

Above: Voltron

Montgomery: As a little girl, loving animation, I was naturally very into Disney princesses. They were my thing. I grew up and got into things like the Batman animated series, anime, action-adventure stuff, and ultimately, when it came time for me to pursue my career, I was able to get a job in the action-adventure side of animation. It’s a very male-dominated side of the industry. It’s very much geared toward boys and young men. Myself, growing up liking it, I didn’t really understand why people weren’t gearing this toward women or even considering them an audience at all.

I spent a large portion of my career just making shows about boys for boys, savoring the chances I would get to have a woman on screen for five minutes or so and I got to draw her. It’s been an uphill battle for a long time. It’s only really been recently, working on Voltron, that we’ve finally been able to get some studio heads and other people to realize that we have an extremely large audience of young women, and there’s an audience watching animation for women.

Across the board, there are more women gamers than ever. There are more women coming into the industry. Even conventions are attended by more and more women. It’s been a slow process, but it’s exciting to me, and I’m happy that it’s starting to have a happy ending. I hope it just keeps going from here.

Takahashi: I first started formally covering games at the Wall Street Journal in the San Francisco office. I got that position because I was the only one in the office who was young enough to be playing games at the time. Every now and then, a couple of times a year, Walt Mossberg would go on vacation and they needed a sub, so I would write game reviews for the first time in the Wall Street Journal. Air Warrior was one of them.

I was trying at the time to explain games to people who didn’t play games or understand them. Wall Street was run by very much that kind of people. They saw games as a small industry, a niche, a subculture, something that was a stepchild to the movies and other things. Over my whole career, this has been the struggle for games, that they’re somehow a stepchild to something else and they’ve never merited being the central thing.

Explaining games to people who didn’t understand them became a good job, especially as games have grown up. Some estimates have the industry at $116 billion a year, $70 billion for mobile games alone. We all know they’re a big deal now. As a group, the younger folks here are lucky, because — I wrote about a lot of people who were struggling to communicate this same thing upward, to bosses and CEOs and people who had budgets to allocate. It’s been a long struggle for all those people, and now you’re arriving at a very good time for the game industry.

Above: Eat your heart out, Epcot.

Lokum: That’s a good point to make. There’s really no other medium where you can get in there for hundreds of hours and interact. At Universal we’re a story-driven company. It’s about content. What you’re doing is important content to us.

Games have grown up. I get multiple emails every week asking, “How can we work with Fortnite?” This is from executives all throughout the company. It’s top of mind. People think about games. This is a great time.

Gale: I’ll start this with one of my favorite quotes. “If you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans.” I grew up in St. Louis, Missouri. I learned to draw copying pictures out of Disney picture books. My ambition was to go to California and work for Walt Disney. When I got a little older, I started copying pictures out of DC comic books, and my ambition was to go to New York to work for DC and Marvel and Mad magazine.

Then I picked up a movie camera when I was in high school. I said, “This is cool. This is what I’ve gotta do.” I went to USC film school, managed to get myself in there. Much to my parents’ chagrin, because if you’re from St. Louis you don’t tell people you’re going to California and going to Hollywood. But they were cool enough to let me go to school out here. I met people who were as passionate about the movies as I was. It was where I met my partner Bob Zemeckis, and we decided to team up and start making movies together.

The story I most like to tell is that we wrote the script for Back to the Future in 1980 and 1981. We were hired by Columbia Pictures to write it, because we’d done our previous picture there. They rejected it and gave it back to us to try and set it up someplace else, because that way they could make their money back.

The screenplay for Back to the Future was rejected more than 40 times. Every studio in Hollywood rejected it at least twice. Producers rejected it left and right, for all different reasons. It was too nice, too sweet. We heard over and over, “Take it to Disney. It’s very sweet. Go to Disney.” Comedies like Porky’s and Stripes were the big movies at the time, raunchy movies. So we thought, “Maybe they’re right. Maybe this belongs at Disney.” This was the old Disney, before Michael Eisner took it over.

We took a meeting over there with an executive. We walked into his office and he said, “Are you guys out of your minds? You’d submit this movie to Disney? This is a movie about incest! You’ve got the kid and his mother in this car! We’re Disney! We don’t do stuff like this!” So we didn’t make it at Disney.

Above: Most of the contest entries came in for Back to the Future.

I tell this story because Bob Zemeckis and I never stopped believing in Back to the Future. George Bernard Shaw once said that a reasonable person adjusts his views and goals to fit the world. An unreasonable person tries to adjust the world to fit his goals. Or her goals. Therefore all progress depends on unreasonable people. Bob and I were two of the most fucking unreasonable people you could ever meet. Somehow we figured out how to make Back to the Future, and we did.

Not everybody can be the grand prize winner here. Out of — how many submissions do we have, 500? We all looked at 20 of them, and most of them were really good. You guys all floated to the top. More of you are going to get rejected. But that’s okay, because you learn from rejection. Just because you get rejected means that the judges know what the fuck we’re doing, because maybe we don’t. Or maybe there’s more than one game here that deserves to be made.

No matter what happens here, if you care, if you have the passion, if you really give a shit and you have that drive and insanity and ambition to keep on going, then keep on going. The world needs you. The world needs what you can do. The world needs what you can bring to it. The history of invention in technology is full of people that were laughed at and ridiculed and rejected for ideas that were thought to be stupid or crazy or just not practical, and we’re here.

If you’ve never read the book The Innovators, by Walter Isaacson, which is a fabulous book covering the history of the computer industry from Babbage all the way to Google, do yourself a favor and read that. It can be very inspirational to me, and it will be to you, to find out what all of these people that we consider to be the founders and the gods of this business, what they had to go through to get there. It’ll help you get up in the morning and keep fighting that fight.

Lokum: All of you guys are really winners right now. This is kind of a once in a lifetime experience. Take it in and, once again, we hope to help you in the next step of your career. To Bob’s point, you’ll make what you put into it. We want to encourage you and give you the tools to get back what you put into it.

Throughout your careers, if any of you had one mentor that gave you a piece of advice that really influenced you and helped you, what was that?

Above: Indie devs will have a chance to pitch a Back to the Future game.

Edwards: I’ve had direct mentors. Some of these were people I didn’t think of as mentors at the time, but in hindsight they absolutely were. They were my Obi-Wans and Yodas and whatever clichés you want to use. In the moment I didn’t realize that they were trying to correct me. One of the most powerful pieces of advice that one of them passed on to me was actually the wisdom of Mark Twain, where he said, “Comparison is the death of joy.”

I use that in a lot of lectures these days when I talk about advocacy. Comparison is the death of joy. One of the things I’ve dealt with myself, and a lot of people in the industry as well — we all deal with imposter syndrome. A lot of that is built on comparison to others. Artists who look at other work and think, “I’ll never be that good.” It’s one of the reasons why, when I give lectures about this, I’ll put up a slide with a Rembrandt portrait and a Picasso portrait and ask people to tell me which one is better. There’s no answer. The thoughtful person will realize that you have to just focus on what you can do best and don’t worry about being somebody else, or doing what somebody else is doing.

If you see someone around you who does something that you think is better than you, guess what? You may have found a mentor. Go ask them: “I’d love to learn how you did that.” If they don’t want to teach you, that’s their issue. Go find somebody else who can. Keeping your focus on exactly what you’re capable of doing and what you want to do, rather than comparing to everyone else around you — I know that for me, that was extremely powerful advice.

Part of the reason I stuck with a career that’s been so bizarre, with all these different paths — conventional wisdom would have asked why the hell a geographer is working at Microsoft. Why is a geographer working in video games? Because I wanted to. I didn’t want to compare myself to what other geographers were doing. I set my own path and I’d encourage you to do the same.

Montgomery: Unfortunately my story is very personal, and really only applies to me, but I’ll tell it to you anyway. [laughs] It ties to what I mentioned before. I was working on shows about boys for boys, and occasionally being able to get a woman character in there. I had a friend, a producer, come in one day and he said to me, “My wife reads a lot of manga.” Manga, as you know, covers every subject. There’s manga about tennis players, a manga about baking a specific kind of muffin. It’s every weird little niche. His wife was really into certain manga series because they appealed to her.

He said to me, “Lauren, you’re in a position where you can effect change. You can make things for women.” I’d always known I wanted to work on content that included women more, but I don’t think it was until that moment that I realized how I needed to not just accept that was given to me and I needed to push harder for it.

That was a turning point, purely for me. I don’t know if it applies to you guys. But maybe at some point in your career you’ll have someone who comes to you and says something that snaps things into sharp focus. Maybe you’ll find yourself in a position of power where you can push for those causes that you really believe in. That’s my story.

Above: Turok: Legacy of Stone

Gale: I had really two mentors. A writer-director, John Milius, and Steven Spielberg. It’s really very simple. Bob Zemeckis and I had written a script. Milius was a legendary graduate of USC film school. If you don’t know who he is, his most well-known works — he wrote Apocalypse Now. He was the writer-director of The Wind and the Lion, with Sean Connery and Candice Bergen. He wrote and directed the infamous Red Dawn. There’s a great Netflix documentary called Milius about him, that really encapsulates what filmmaking was in the 1970s. He also wrote the famous Robert Shaw speech in Jaws about the USS Indianapolis.

Anyway, Zemeckis and I gave Milius a script we’d written on spec. That means we wrote it ourselves, without getting paid for it. John read it, he liked it, and he hired us. That’s the best thing that can ever happen. A professional likes your work so much that they encourage you to continue. Hiring you to write a script, in my business, at that time was the greatest thing that could happen to you.

Milius was good friends with Spielberg, so Spielberg came to read some of our work. He said, “Jeez, you guys can write. You’re talented. Make a movie for me.” It was that simple. We found people that liked our work so much that they were willing to hire us.

Takahashi: I’m a journalist, and my job is fun because I get to talk to a lot of people. I talk to people who might be enemies of each other — one person might be on one side of the story and another person might be on the other side of the story. What I’ve always liked about that is how people surprise me. They always do something or say something that I didn’t expect. I try to keep talking to people until I find something like that.

One reason I do that goes back to my father. He was a strict Asian dad in a traditional Asian household. The paramount thing was to get good grades in school. I was going down the track of being an engineer or a doctor or something like that, until I got a C in calculus and a C in physics. This was a disaster, especially because I had an older brother who aced all of these things.

When it came time for me to go to college–my brother went down the traditional route, but he struggled with it. He eventually found something different. When it was my turn to go to college, I was kind of dreading what my dad would actually say about this. I fulfilled all the requirements for business school, and I tried to take some science and math in college as well, but I was drawn more to writing. I’d always wanted to be an English major and write.

I told my dad, “This is what I’m going to do. Journalism is fun. English as a major is what I want to do.” He was very supportive, in the end. He surprised me. It was because, when he was young, he had no choice but to do something really practical. He became an accountant. What he had really wanted to do was study history, be a history teacher, and he’d always regretted not going where his passion was. So for me, he told me, “Do what you want.” That was good advice.

Lokum: We have some great storytellers on the panel. As I mentioned before, you’re all storytellers in your own right. You’re extending the fiction of these properties for game. I’d love to hear from you guys what you think makes for a successful piece of entertainment, whether it’s a video game, or another kind of new technology. We know from Bob that picking cherries off of trees doesn’t do it. But what’s your opinion of the space today and what makes storytelling — whether it’s TV or movies or games — compelling to you?

Above: Battlestar Galactica Deception

Gale: The legendary screenwriter William Goldman said, “Nobody knows anything.” Truer words were never spoken. Nobody knows. That’s what’s so exciting about being in the entertainment business. There isn’t a template.

One of the life lessons I learned — you start off and you go to grade school. You need to get good grades and go to junior high. Get good grades and go to high school. Get good grades, pass your SATs, and get into a good college. Get into college, do everything they tell you, and you get out, but nobody prepares you for what happens after that, because nobody knows. If you go to law school, yeah, okay, there will be some folks from law firms recruiting, or in some other fields. But if you’re trying to be in the entertainment business, whether it’s gaming or movies or any kind of storytelling, they’re not waiting for you. You have to figure it out. You have to make your own path.

Just because everyone says, “This is what’s popular right now,” that doesn’t mean it’s going to be popular next week, or next month, or next year. And so you have to amalgamate everything that’s going on. Being creative, trying to figure that out, is really hard. You have to remind yourself that there’s no right answer. You can make a clone, make another Candy Crush, but who needs to do that? Anybody can do that. You need to do something else.

What that is, nobody will be completely sure. Nobody knew they needed an iPhone until Steve Jobs gave it to them. What makes a successful piece of entertainment, it could be anything. I would say that the one thing you ought to keep in mind is that, whatever medium you’re working in, try to think about what are the goals in that particular medium.

I don’t mean, “Just make a big hit.” I’m talking about the difference between — say you’re designing an arcade game. What’s the goal of Mortal Kombat? The goal is to get the player to put a quarter in. If you’re writing a network TV show, the object is to get someone to sit through a commercial and see what happens. If it’s a Netflix show and there’s 15 episodes to stream, you have to make the first episode good enough that they want to watch the second one. If it’s a movie, you have to get people to tell their friends, “You gotta go see this movie!” If it’s a video game, a freemium game, you want people to like it so much that they’ll spend a dollar to buy something stupid to keep playing the game. [laughs] If it’s a console game, you need to come up with a world that’s so cool that they’ll spend $50 to have it.

Those are the kinds of goals I’m talking about, that will help you figure out something to keep in mind. Keep in mind the goal of what you’re doing. How do you do that? What’s going to get people to do that thing?

Above: Nike’s Mag shoes are based on the self-lacing pair in Back to the Future II.

Edwards: Along with that, in a complementary way, you have to think about your own metric for success as a professional doing this kind of work. For some people it’s the monetary side, or for a lot of people. We want to make a living off this. We want to survive and pay our bills and have all the good things in life. But for a lot of people that’s not the priority. People have full-time jobs already and make games on the side, and they’re perfectly happy with that. Games become a creative outlet in addition to something else they love, and that’s perfectly fun. Others go full-time into games because that’s where their passion lies and that’s fine too.

Between both of those, it’s only about what you personally, introspectively — what are you trying to get out of this? Is it a creative outlet for you? Are you trying to make money? Last week I was in Teheran at the Teheran Game Convention, which was fascinating. One of the developers there, his personal metric for success was just, “I want someone outside of Iran to see my game.” Because it’s very difficult to make that happen right now. That’s it. That’s all he wants. He doesn’t care if it makes money. He just wants his creative vision to be shared outside of that bubble universe they’re in right now.

For you — I’ve met game developers who just want someone to recognize their passion. They feel that, if they can influence at least one person with their creative vision, they’ve made a difference for somebody. For others, they want to talk to a million people, at least. I’d encourage you all to think introspectively about that. We all have to deal with the reality of paying our bills and satisfying publishers and all that stuff that’s part of the business side of games. But because this is a creative art form, it’s extremely personal for everyone. We have to reflect on what success looks like for each of us.

Gale: Let me jump in with something that reminds me of. One thing we learned in the movie business is you want your movie to at least be good enough for you to get another job. Somebody sees your game; maybe it’s not a financial success. Maybe it’s a total disaster. But if you come up with something cool in it, knock on wood, somebody’s going to notice that and say, “I want that person to work on this project. They came up with something really cool.”

Like I say, if you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans. You don’t know where life is going to take you. But if you’re following your passion, you have a much better chance.

Montgomery: It is about following your passion. There’s not really a checklist of what you need to make something a success. There’s definitely a checklist of what’s hot now, but ultimately you need to be proud of the project you’re working on. You need to be invested in it. You need to want to play it yourself. That’s always something that — my teams and I have always followed that when we make the shows we make. We’re also fans of the shows we make. Being a fan of your own work, loving what you’re doing, hopefully that will show in your work, and other people will feed off that.

Takahashi: My advice is to zoom in and zoom out. The zooming in part, there’s an example in the makers of Cuphead. Their game and the controls — it’s very difficult, very hard to play. They always wanted to make the kind of game they grew up playing. From moment to moment, when you’re playing Cuphead, if you screw up you’re dead. They paid this laser-like attention to what’s going on with your fingers and the controller. That turned out to be a brilliant idea.

Zooming out is something we try to do at our GamesBeat conferences every year. It reminds me of what Will Wright used to talk about. The thing that inspired him to make Spore was this video called “Powers of 10,” where you zoom in on something small like a blade of grass, and then eventually you zoom out far enough to see the whole Milky Way galaxy.

By zooming out, I mean think of the game industry as a whole and what’s around it. I come from Silicon Valley. Our conference focuses on things like science fiction, technology, and games, and the intersections between all of them. If you look at someone like Philip Rosedale and Linden Labs, who created Second Life, he was inspired by science fiction, by Snow Crash and other stories like that, to go and create virtual worlds. The idea of creating a virtual world of virtual worlds, a Metaverse, is what he and a lot of other people want to accomplish.

He could have just focused on making a game there, but he’s had to think about a lot of things outside of games that go with it, like blockchain technology as an example. He has a new company called High Fidelity that wants to make virtual worlds interoperable, and blockchain may be the thing that makes that possible, so that you can have a character from one world go to another world and so on. He has this vision only because he’s zoomed way out.

If you zoom in or you zoom out, it may not be exactly relevant to what you’re doing day to day. But if you stop and do this every once in a while, you can get big ideas out of that.

Disclosure: The organizers of the contest paid my way to Los Angeles. Our coverage remains objective.