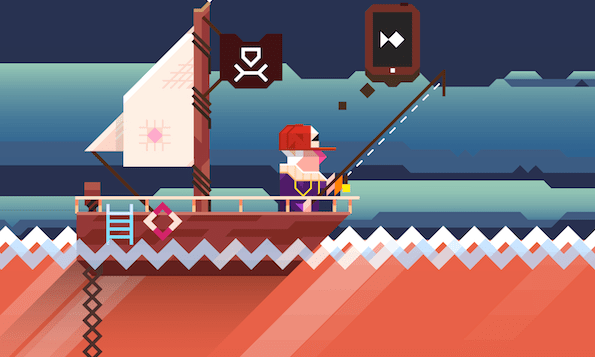

Above: Zach Gage worked on Ridiculous Fishing with Vlambeer.

Gage: There are two ways to look at Apple. You can look at it and say, “This is a company that accidentally turned into a game company.” But I think the other way to look at Apple, this is a company that is intentionally trying to make devices that fit into people’s lives and are for human beings to use every day in their normal life.

Where Apple turned into an accidental game company is that—as they were working on this device that fit in normal life, there was this invisible force of games suddenly becoming more capable, more ready for the mainstream, more ready to burst into culture. Suddenly, when there’s a device that everyone has, games are just like, “Let’s go do that!” Everybody who has the device is ready for games. They’re ready to understand them and play them and be a part of them.

I want to be with the company that’s making things for people, more than I want to be with the company that’s making things for gamers. Coming from doing installation art, when I make games, what I’m interested in is using games and the interactions around games and the skills you need to learn to be good games – that critical thought – to be able to teach skills and broach questions about society and culture that you can’t ask through—either you can’t ask them of people directly, or you can’t ask them as well through other media.

My go-to example would be, about a year ago I released a game called Really Bad Chess. It’s basically chess, but all of the pieces you have are randomized. They’re still normal chess pieces, but you might have five queens or four rooks or only knights. I was taking this thing everyone kind of understands – even if you don’t play chess, everyone knows what chess is and the structure of chess.

Chess is this thing that, in culture, represents the paragon of intellectual competition and fairness. There’s no hidden information, no randomness. It’s just two minds against each other to find out who’s smarter than the other person. I feel like that’s how a lot of people think a lot of things are supposed to work. That’s how they think games are supposed to work, how culture is supposed to work. You find the thing that’s the most perfectly fair competition and you put people into it.

The reality, and the point I was trying to make, is that’s kind of stupid. Fairness isn’t that interesting. Most of the things we really love are totally unfair. Sports are totally unfair. That’s why they’re good. If every basketball team was exactly as good as every other basketball team, nobody would care about basketball. We don’t want it to be too unfair, but having a bit of unfairness is actually what keeps it interesting and makes people care about it.

That’s a message and a question that’s difficult to ask with some other media, but it’s very doable to build a game to ask that question. I think that’s the kind of experience that–when people play this game, they have to step back and look at other aspects of their life and think, “Oh, I did this thing that was totally busted, but I kind of liked that, and it made this game better. Why did it work that way?” To ask those kinds of questions—I don’t want to ask them on the PlayStation. I want to ask them on something that everybody has.

Cash: You have a unique opportunity with games to interact with things and learn things. A game I played not long ago was What Remains of Edith Finch. There’s a part of that game where you go through the motions of doing something – I don’t want spoil it – and you couldn’t possibly get that same feeling from watching a movie, reading a book, or hearing a story. The only way you can experience that—if you did it in real life, what they’re simulating, you would experience that, but 99.9 percent of people aren’t going to be doing what’s happening in that game. The fact that games can give people an opportunity to experience something in a way that’s not passive is very interesting.

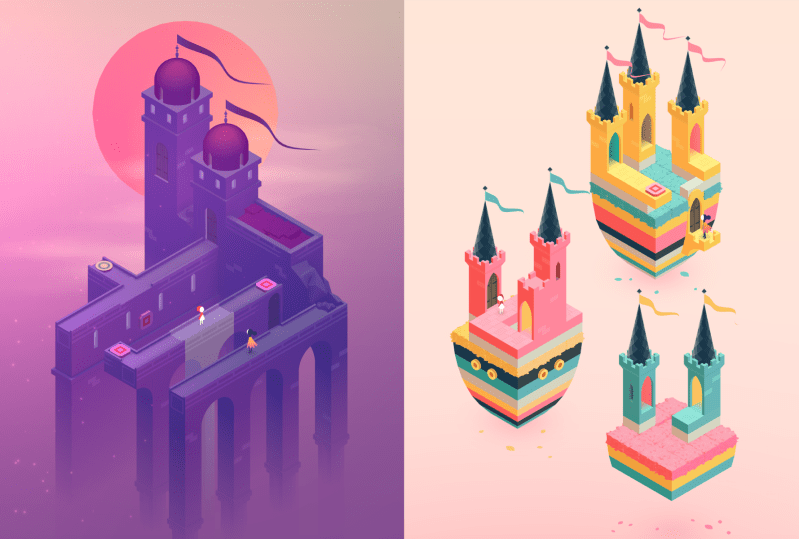

Above: Monument Valley 2

GamesBeat: I ran into the division between hardcore and casual when Cuphead was coming out on consoles. It feels similar in PC. The line between hardcore and casual audiences is very unforgiving. Apple seems to have some ability to move between those. In mobile I don’t detect such a religious attitude from people so much.

Gage: I don’t love the terms “hardcore” and “casual.” What people assume that means is, they assume hardcore means the games are difficult and casual means the games are easy. But the reality is, they’re just signposts to different sets of literacy. Hardcore games are games where people use a controller and explore 3D worlds and they’ve been doing that for a long time. Casual games tend to be cards and dice or 2D things interacting.

Is chess a hardcore or a casual game? Is solitaire? Solitaire is really hard, and I’m really bad at it. Is Bejeweled a casual game? Everyone would say it’s casual, but the people who are good at Bejeweled are really good. You couldn’t take someone who’s good at Halo and just put them into Bejeweled and say, “Compete with this grandmother.” They’d get wrecked. Bejeweled becomes very difficult.

Looking at those terms in that way is a bit misguided. When you start thinking about them as literacy groups or audiences, it becomes a very different kind of thing.

Gray: When I think about the games we make, Monument Valley is vaguely a game. It’s more interactive entertainment. It’s not a difficult game whatsoever. In some ways, people might pigeonhole it as something hardcore, because it’s seen as an artsy game, and it costs money. But in other ways—you can put it in front of someone who’s 70 years old and they can get through it. It doesn’t seem to make as much sense on mobile as on other platforms.

Gage: It’s not my game, but I’m pretty sure that people who are really good at Candy Crush are really good at video games.

Cash: It’s easy to throw labels on certain things. We’re all guilty of that in any industry. It’s kind of like — there’s pizza places that are fast food pizza places, there’s mid-grade pizza places, and then there’s the Chef’s Table episode on pizza where this guy’s been studying pizza for 40 years and perfecting every detail. Is pizza a casual food or is it culinary excellence? It depends.

I don’t know if that’s a good analogy, but—“casual” gets thrown around a lot with mobile because you play mobile games in casual environments. You’re waiting for the bus. You’re on the train. You’re waiting for a movie to start. That’s what a lot of people consider casual. But it doesn’t mean the game itself is any more or less complex than something where you hook up a console.

Above: Alto’s Odyssey

Gage: Generally where the line comes down—games people would consider casual are designed with broad accessibility in mind, and games that are considered hardcore sort of shortcut that accessibility. They say, “We’re going to make a game assuming you know how to do a million different things.”

That’s perfectly fine, but it becomes weird to me when people start trying to stigmatize a game that’s built around being accessible and bringing new people in. That doesn’t seem to say that a game is easy or hard. It just means that a game is welcoming. It makes sense that games on mobile would be welcoming, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they would be any harder or not.

When you say that the games coming out on the iPhone are straddling that line, I think it makes sense. When you’re developing a game for the iPhone, you’re looking at a potential audience of millions and millions of people. Way more people than exist on the Xbox and PlayStation and Nintendo added up. The mobile audience is so much bigger. It makes sense to build games that might convert new people, because new people are there.

If you make a game on the Xbox, there’s a legitimate cap of, say, 100 million people that can experience your game. That cap doesn’t exist on mobile. If you look at the download numbers on Pokemon Go, it’s way over 600 million people. What does it take to design a game that could appeal to that many people? If you’re putting a game into that environment, why wouldn’t you make it accessible and try to bring people in?

I can’t speak for you guys, but I think that’s what’s exciting about doing things on mobile. You’re not making a game that’s going into a niche. Every console game, every game you’d say is hardcore, that’s a niche game. It’s a game for gamers, hardcore gamers. I love those games. I’m in that niche. It’s a big niche, a big market. But when you make a game on mobile, you’re making a game that’s not for a niche. It’s for a huge contingent of the world. When you do something for that market, you need to build it in a way that’s accessible.

GamesBeat: If you could finish this sentence: “I wish Apple would…” What would that be?

Cash: I understand some of the hardware limitations, but it would be awesome to see haptic feedback on the iPad. I’m sure that’s not something they’re not thinking about, though.

Gage: I’d love to see Game Center come back even stronger than it is.

Cash: I agree with that as well.

Gage: It’s a big missed opportunity, to just see it sitting around.