Many mobile game developers launch their titles on both iOS and Android at the same time. But there’s a batch of talented iOS game makers who prefer creating exclusives on Apple’s platform. They think that Android’s fragmentation makes it too hard to do simultaneous launches.

In 2017, games made up a larger share of Google Play’s consumer spending compared to iOS, but consumers spent nearly two times more on iOS games than on Google Play games, according to a year-end report by market researcher App Annie.

At the Game Developers Conference, I was able to sit down and chat with three all-star iOS game developers: Dan Gray, head of studio at Ustwogames, maker of Monument Valley and Monument Valley 2; Zach Gage, maker of SpellTower, TypeShift, and Ridiculous Fishing; and Ryan Cash, founder and creative director at Snowman, the creator of games such as Alto’s Adventure and Alto’s Odyssey.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview. I also interviewed Apple vice president Greg Joswiak about the importance of games to Apple.

Above: iOS devs being creative: Dan Gray (left), Zach Gage, and Ryan Cash (right).

GamesBeat: How many years has it been on iOS for each of you?

Dan Gray: Since the beginning, really. We were talking about this recently. Ustwo in general, the thing that kicked the studio off was iOS, from a design perspective. The company’s been working in mobile about 12 years

Zach Gage: I think I’ve been doing it since before the iPhone 3G, but I wasn’t right when it started. A couple of months into it. The App Store was open by then.

Ryan Cash: I used to work for a software company that made productivity software. They were there on day one for the iPhone, and same for the iPad, being a Mac software company before. I left in 2012 to start my own company. That was our first year in the App Store as Snowman.

Gray: Before I turned up, we made a voice replication app. You’d hold the phone up to your mouth and talk into it and create all these different crazy mouths and noises and stuff. It’s the sort of thing you’d make at the beginning of the App Store.

GamesBeat: To what degree are you exclusive to iOS now or not?

Gray: Monument Valley one and two were both exclusive to iOS for a short period, and then we did the Android version later on.

Gage: All my stuff is focused on iOS. Another company ports my games to Android eventually, but it’s whenever we can get it together to do the contract and have them port it. It’s not a set thing. But for me, I’m focused on iOS stuff.

Cash: That’s the same for us. With Alto’s Adventure, it took us about a year to get to Android, and we had another company do that. Our focus is on iOS first.

GamesBeat: Why is that?

Cash: For us, it’s been the bread and butter since the first iPhone was announced. That’s all I know. But I think more than that, it’s for a number of reasons, one of them being that we know people will experience the products we make the way we intend them to. We know exactly how we’ll experience the product. We know all the color will look the same. We don’t have to account for device fragmentation, OS version fragmentation. But it’s more that the way we want you to play our game and enjoy it, you’ll be able to do it. On other platforms we’re not as sure.

Gage: That’s a big thing for me too. I came into this originally from doing fine art, doing interactive art, and so the idea that you—the first thing I released was a thing called Synth Bond, which was basically a sound toy. Coming from interactive art, it was this amazing experience. I’m used to dealing with lots of different kinds of technology, putting them in a gallery and trying to get people to understand how they work. Now everybody has this one piece of technology in their pocket all the time, and I know exactly how it works. I can design a ton of different experiences that I know will pan out for them in a certain way.

Especially for me, as a solo developer, trying to deal with something that’s as fragmented as Android and the Google store—it’s a lot harder. That’s one thing as far as why I’m not focusing on Google. The other thing is, iOS is such an exciting space, because it’s where the people I want to reach are. It’s the people that appreciate good design. Basically normal human beings who don’t really care about games. You make something and suddenly they can play it.

To me that’s a much more exciting audience than developing on consoles or PC, where there’s a more crunched audience that really cares about games, that are very fanatical about games. I’m interested in games being able to break out of the game space and become a normal cultural institution that people are interested in, like music or movies or whatever.

Even though it seems like that kind of thing would have potentially less power, because people aren’t as directly and intensely engaged with it, I think that ultimately that kind of medium and position in society has way more cultural power, because it becomes this passive contributor to the things that people are thinking about, the way they talk, the way they approach things. To me that’s why it’s exciting and why doing stuff for mobile is particularly interesting.

Gray: I joined the company five years ago to basically set up a games team. The way we set up the games team was to look at what we perceive to be the values of Apple. We wanted to launch our games on this platform, and we set ourselves up like, what would a first-party Apple studio look like? Which is basically what happened.

It’s things like, everything we make had to feel precious. It had to feel not necessarily just like entertainment, but have value. We wanted to have amazing attention to detail in everything we made, and make people feel special when they played it. Those values, between the hardware we’re delivering on and the games we’re making, lined up perfectly. It’s done all right for us so far.

GamesBeat: Did you view yourselves as Apple fans at the start? Or more just valuing the things Apple values?

Gray: No, we already were. Even before I turned up at the company, it was all about Apple. Our relationships were always with Apple.

GamesBeat: The common wisdom seems to be that if you do Android and iOS at the same time, you reach the widest possible market. The business decision is to do as many platforms as possible. But in some ways I’m starting to hear that it’s a business decision for you guys to do iOS first.

Cash: Another reality that can often be overlooked is that for small teams, it’s just not an option to do that many platforms at once. For us, we have to prioritize not only the platform that works the best, but also the platform that fits our products the best. We would have to delay the shipping time by many months if we wanted to hit both platforms at the same time. Because of the things that Zach and Dan both mentioned, which I also agree with—it’s just, why put in that extra six months or whatever it is to do something for a platform that just isn’t as good, quite frankly?

Gray: We had a big delay on Monument Valley 2, obviously, between the iOS version and the Android version. People asked what was taking so long. We once took a photograph and laid out all of our Android test devices on the floor. It was 80 devices in the middle of the studio. “We’re working as hard as we can!”

Gage: There’s a tendency with how many businesses are run, and how most consumers and technology watchers think businesses are run—everyone assumes that every business is run to scrape every single penny off the sidewalk that they can. I think that the reality of running a business is not at all like that. You don’t sit down and say, “How can I make the most money possible?” For me it’s more like, “How can I do the thing I love, stay happy, get something out that people enjoy that represents me, and do it in a way that keeps me afloat?”

If I can do all of those things, I’m good. I don’t need to stretch out the box into spaces where I’m not comfortable, or where I think the product may end up getting damaged or not presented in the way I want.

Above: iOS devs contemplating the future: Zach Gage (left), Dan Gray, and Ryan Cash.

Cash: This is me speaking for Apple, which I don’t want to do, but I think that philosophy also mirrors—if you look at other tech companies that make refrigerators and dishwashers and TVs and everything you can find in an electronics store. Then you have Apple which just famously says no. I think it’s what you say no to that ends up becoming who you are. The power to say no, even if there might be money on the table—is that a long-term decision that fits your values, your vision, and what you enjoy?

Gray: I’ve heard that phrase so many times, that idea that you’re leaving money on the table. But like you said about happiness, just the idea of focus—it’s hard enough to make a game anyway. Just creatively. You find yourself changing levels one or two weeks before the game launches. The idea of having to do that at the same time as all the technical requirements of 100 different devices—it just enables you to concentrate on you being happy, not stressed, and being able to deliver the best game possible first.

Gage: It’s a funny thing that happens specifically around technology. There’s a big feeling that tech is easy, even though most people don’t even really know how their phones work. It’s weird that they say, “Why don’t you release on Android?” Well, why don’t you build a phone yourself? It doesn’t make sense. It’s not something you’d apply to any other business. You don’t walk into a restaurant wanting a hamburger, see that they don’t have hamburgers, and say, “Why don’t you guys make hamburgers? You’re leaving money on the table!” It’s so weird.

Cash: I was just going to say, if you’re at a restaurant sitting there and wondering where your food is. it’s not as if they’re not bringing it out because they don’t want to. It’s for a reason. Things go wrong in the back. It’s busy. There are lots of moving pieces. It’s not that simple.

I think we’re all guilty, to an extent, of making those assumptions about industries we’re not familiar with. I remember, growing up, reading on a site like IGN, seeing that Gran Turismo is delayed. Why is it delayed? That’s crazy! I want it now! But it’s made by a massive team. There are people behind it. I think one thing, to speak to something you said—your overall happiness, that’s something we’ve been thinking about a lot lately. Finding the right balance where you’re happy and love what you do. Otherwise I think you’ll burn out and not enjoy it.

Gray: What’s genuinely helped us—the thing you’re talking about, where people just don’t understand. Players, customers, don’t understand. Why is this delayed by two weeks, four weeks? A lot of the time it’s because in the past they’ve seen an icon and they think any of our games are made by a company of 200 people. Actually, what we’ve seen is—after a couple of the stories we’ve done where it has photos of the studio and the people making it, people realize, “Okay, this is made by humans. It’s made by a small studio, a small team.” We’ve had people become a lot more friendly than they might have been two years ago, because they know it’s not 200 people making Monument Valley.

Above: A customer looks at Apple’s new iPhone X after it goes on sale at the Apple Store in Tokyo’s Omotesando shopping district, Japan, November 3, 2017.

Cash: Reaching out to people who email us and ask why our game is delayed—for example, with Alto’s Odyssey, we had announced it was launching the summer of last year, and we had to ultimately make a decision for the good of the game to delay that into February. People were disappointed. They tweeted and commented on Facebook and emailed us. But when we reached out and replied and explained why – that we’d rather do it right than do it earlier – when you have that conversation and the dialogue opens up a bit, most people understand.

But I can’t tell you how many emails we’ve gotten that are kind of nasty about all kinds of things. As soon as you reply – and this is true in almost any industry – they realize, “Oh, there’s a person here. It’s not just a graphic that I’m sending ones and zeroes into.”

GamesBeat: Creatively, it looks like you guys all feel it’s the right decision to develop on iOS. What has reinforced that, looking back?

Gage: I’ve been an Apple person for a long time. When I was nine and Apple stock was at 16, I told my mom to buy a bunch of it. [laughs] Honestly, the original reason I developed on iOS was because it seemed like a fascinating platform. The multi-touch was captivating. I had a piece of art that I had put on my website, where it got a bit of attention. I put it on iOS and it gots tons of downloads and made a bunch of money. People emailed and thanked me. I was like, “What is this magical box? This is incredible!” Then I basically tilted all of my focus into developing for it.

What’s been cool, as it has evolved—I’ve gotten a pretty good sense that the interests of Apple have aligned with the things that I’m interested in. I get the sense that Apple was trying to push paid games when everyone was going to free-to-play. They’ve redone the store so that they can promote the people behind games. They stuck with—Apple has this thing where they’ll stick with a technology until they see something that they’re absolutely sure is better, and then they’ll force everyone to move to it, even though people don’t really want to. Then you go to it and you realize, “Oh, this is better.” That’s what I’m interested in. I want to be on the device that has the things that are new and actually interesting.

One thing that’s been big for me lately is I love the haptics in the phone. I think the haptics in the iPhone are the best feature that’s been added to the phone in years. They’re leagues beyond anything else. I love my Nintendo Switch, but I think the haptics in the iPhone are way more important than HD rumble in the Switch. The reason is because on the phone, everybody plays their games on mute. All of the roles that sound plays when you’re designing something, that gets shut out on the phone. But now, with the haptics, you can do all the notification stuff and attention things you would normally do with sound using the haptics. You can design games that feel good and “sound” good, even when they’re played on mute.

That kind of tech, to see that stuff come out year after year—oh, now we can do high-density pixel displays and build games around that. Now we have haptics. Now we can do these new things. It’s a blast to develop on that, but also, for me personally, it’s fun. Every couple of years Apple comes out with this new design toy that I get to explore. What could this do? Where does this go?

Cash: It’s never gimmicky, either. It always has meaning. Someone didn’t just think of it and put it in there the next day. In many cases it’s probably been thought over for years. You know it’s refined. You know it’s probably staying there for the foreseeable future.

Above: Apple’s new headquarters

GamesBeat: Historically, the way I thought of the game platform companies — we have dedicated, intentional game platforms like Sony, Microsoft, and Nintendo, and then we see the accidental game companies like Amazon, Google, and Apple. Do you have a feeling about that, that it’s an accident that you’re on their platform and games have become this big thing?

Cash: As far as I can remember, computers have always had a couple of basic games installed out of the box, or easily available. Everyone knew gaming was there. But I don’t know if anyone knew how big mobile gaming would be.

Like Zach was saying earlier, one of the reasons iOS is so exciting for us, and for mobile in general—when someone buys a PS4 their intent is clearly to play video games. Maybe they got it because you can watch Netflix too, but the main reason is to play video games. Whereas most people bought an iPhone because they wanted the best phone. You have access to all of these people who don’t consider themselves people who play video games. Now you can reach that audience in a way you could never reach them before.

I’ve found so many new people who still wouldn’t consider themselves someone who plays video games, yet they play video games every day on their phone. That’s a unique opportunity. It’s really interesting for us.

Gray: The Sony example you gave is what happened to us. The week we launched Monument Valley, we had our Sony rep come to the studio and congratulate us. He said, “We really need you guys to sign up with us and develop a new game for our platform. How much will it cost for you to do this?” But we literally couldn’t do it. When someone’s made that decision to purchase a game console, they’re already a gamer. For us, the thing that’s been most amazing is to take the idea of what’s great about video games and let a mass audience understand that and experience it for the first time. Many people aren’t going to sit there and drop hundreds of dollars on a piece of hardware specific to gaming.

If I rewind five years to when I first turned up, the reason I joined Ustwo was because I found it fascinating to go into an environment of people who didn’t develop games and develop games in there. I didn’t know how it was going to work, but I knew it was going to be different. I knew they would be designed like applications are designed: for everyone.

When you talk about these accidental platforms, there are a lot of similarities there. You manage to make fresh new things if you don’t come at them from the same perspective. A lot of hardware manufacturers or existing games companies can be quite narrow-minded in what they accept as video games. It’s a really easy way to be fresh.

Cash: A perfect example is how Snowman accidentally got into making video games. We had no intentions of doing that. I left my previous job to make a reminder app called Checkmark. That was our first iOS app. At the time I had no plans to get into gaming. I grew up playing games, but I was never the world’s biggest gamer.

Above: Sophisticated iOS developers: Zach Gage (right), Daniel Gray, and Ryan Cash (right).

GamesBeat: Accidental game developers.

Cash: Exactly! We were about to start working on a utility app for iOS that was going to be this unique twist on a way to store voice memos and images and notes privately on your phone. This is back in 2012. Right before we got started on programming – we had already done the UI mockups – the designer said, “Hey, this reminds me of something.” It was that toy from the ‘80s, Simon, that big physical game that had the colors you’d tap out. We thought we could make that instead and see what we could do with a digital take on a physical toy. What could you do when you weren’t bound by physical restraints?

We started exploring all these ideas on how you could do a modern version of that game in a software environment. None of us knew how to make games. None of us even played games that actively. This was a game could non-gamers could make, though. It’s essentially shapes and colors and sounds. It was an easy step into that environment. Next thing you know, here we are making games.

What we’re excited about ourselves is just the fact that games are art. “Game” is such a broad term now. It can range from something like Call of Duty to Candy Crush and everything between and around that. We approach it as art. The fact that people can be interested and excited by it, even if they don’t play it, is really interesting to me. Someone can enjoy the things we make even if they don’t enjoy playing it themselves. You can hang a Monument Valley poster on your wall, even if you don’t play puzzle games.

My grandparents, for example, when I showed them the first trailer for Alto’s Adventure, they made me play it three or four times. They have a print of the game hanging on their wall. It’s not just because it’s their grandson’s, but because they genuinely like the way it looks. But they’ll never play the game. That’s a really exciting thing to see.

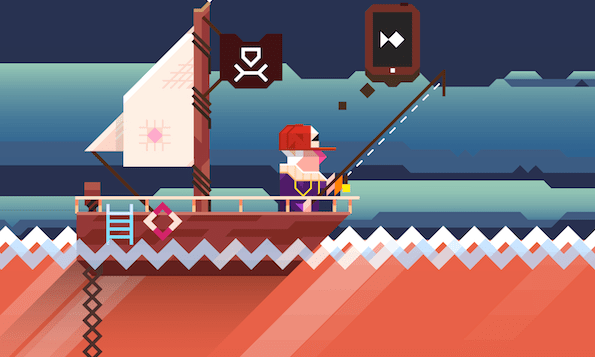

Above: Zach Gage worked on Ridiculous Fishing with Vlambeer.

Gage: There are two ways to look at Apple. You can look at it and say, “This is a company that accidentally turned into a game company.” But I think the other way to look at Apple, this is a company that is intentionally trying to make devices that fit into people’s lives and are for human beings to use every day in their normal life.

Where Apple turned into an accidental game company is that—as they were working on this device that fit in normal life, there was this invisible force of games suddenly becoming more capable, more ready for the mainstream, more ready to burst into culture. Suddenly, when there’s a device that everyone has, games are just like, “Let’s go do that!” Everybody who has the device is ready for games. They’re ready to understand them and play them and be a part of them.

I want to be with the company that’s making things for people, more than I want to be with the company that’s making things for gamers. Coming from doing installation art, when I make games, what I’m interested in is using games and the interactions around games and the skills you need to learn to be good games – that critical thought – to be able to teach skills and broach questions about society and culture that you can’t ask through—either you can’t ask them of people directly, or you can’t ask them as well through other media.

My go-to example would be, about a year ago I released a game called Really Bad Chess. It’s basically chess, but all of the pieces you have are randomized. They’re still normal chess pieces, but you might have five queens or four rooks or only knights. I was taking this thing everyone kind of understands – even if you don’t play chess, everyone knows what chess is and the structure of chess.

Chess is this thing that, in culture, represents the paragon of intellectual competition and fairness. There’s no hidden information, no randomness. It’s just two minds against each other to find out who’s smarter than the other person. I feel like that’s how a lot of people think a lot of things are supposed to work. That’s how they think games are supposed to work, how culture is supposed to work. You find the thing that’s the most perfectly fair competition and you put people into it.

The reality, and the point I was trying to make, is that’s kind of stupid. Fairness isn’t that interesting. Most of the things we really love are totally unfair. Sports are totally unfair. That’s why they’re good. If every basketball team was exactly as good as every other basketball team, nobody would care about basketball. We don’t want it to be too unfair, but having a bit of unfairness is actually what keeps it interesting and makes people care about it.

That’s a message and a question that’s difficult to ask with some other media, but it’s very doable to build a game to ask that question. I think that’s the kind of experience that–when people play this game, they have to step back and look at other aspects of their life and think, “Oh, I did this thing that was totally busted, but I kind of liked that, and it made this game better. Why did it work that way?” To ask those kinds of questions—I don’t want to ask them on the PlayStation. I want to ask them on something that everybody has.

Cash: You have a unique opportunity with games to interact with things and learn things. A game I played not long ago was What Remains of Edith Finch. There’s a part of that game where you go through the motions of doing something – I don’t want spoil it – and you couldn’t possibly get that same feeling from watching a movie, reading a book, or hearing a story. The only way you can experience that—if you did it in real life, what they’re simulating, you would experience that, but 99.9 percent of people aren’t going to be doing what’s happening in that game. The fact that games can give people an opportunity to experience something in a way that’s not passive is very interesting.

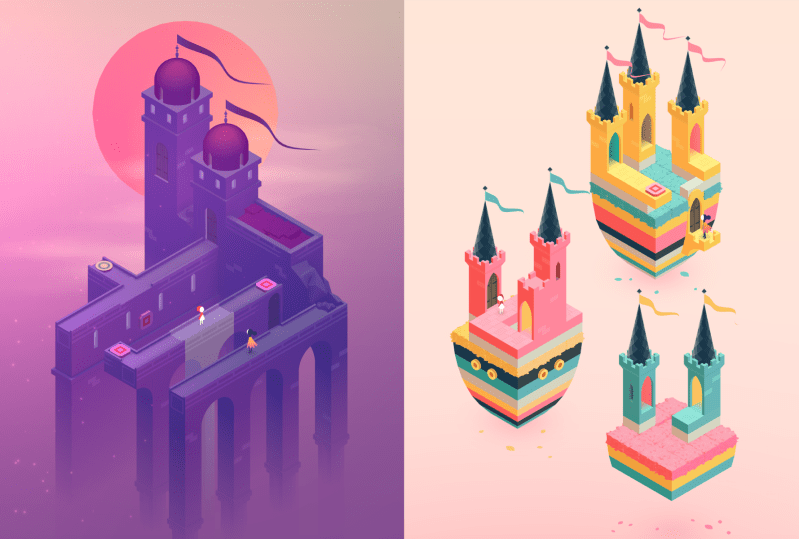

Above: Monument Valley 2

GamesBeat: I ran into the division between hardcore and casual when Cuphead was coming out on consoles. It feels similar in PC. The line between hardcore and casual audiences is very unforgiving. Apple seems to have some ability to move between those. In mobile I don’t detect such a religious attitude from people so much.

Gage: I don’t love the terms “hardcore” and “casual.” What people assume that means is, they assume hardcore means the games are difficult and casual means the games are easy. But the reality is, they’re just signposts to different sets of literacy. Hardcore games are games where people use a controller and explore 3D worlds and they’ve been doing that for a long time. Casual games tend to be cards and dice or 2D things interacting.

Is chess a hardcore or a casual game? Is solitaire? Solitaire is really hard, and I’m really bad at it. Is Bejeweled a casual game? Everyone would say it’s casual, but the people who are good at Bejeweled are really good. You couldn’t take someone who’s good at Halo and just put them into Bejeweled and say, “Compete with this grandmother.” They’d get wrecked. Bejeweled becomes very difficult.

Looking at those terms in that way is a bit misguided. When you start thinking about them as literacy groups or audiences, it becomes a very different kind of thing.

Gray: When I think about the games we make, Monument Valley is vaguely a game. It’s more interactive entertainment. It’s not a difficult game whatsoever. In some ways, people might pigeonhole it as something hardcore, because it’s seen as an artsy game, and it costs money. But in other ways—you can put it in front of someone who’s 70 years old and they can get through it. It doesn’t seem to make as much sense on mobile as on other platforms.

Gage: It’s not my game, but I’m pretty sure that people who are really good at Candy Crush are really good at video games.

Cash: It’s easy to throw labels on certain things. We’re all guilty of that in any industry. It’s kind of like — there’s pizza places that are fast food pizza places, there’s mid-grade pizza places, and then there’s the Chef’s Table episode on pizza where this guy’s been studying pizza for 40 years and perfecting every detail. Is pizza a casual food or is it culinary excellence? It depends.

I don’t know if that’s a good analogy, but—“casual” gets thrown around a lot with mobile because you play mobile games in casual environments. You’re waiting for the bus. You’re on the train. You’re waiting for a movie to start. That’s what a lot of people consider casual. But it doesn’t mean the game itself is any more or less complex than something where you hook up a console.

Above: Alto’s Odyssey

Gage: Generally where the line comes down—games people would consider casual are designed with broad accessibility in mind, and games that are considered hardcore sort of shortcut that accessibility. They say, “We’re going to make a game assuming you know how to do a million different things.”

That’s perfectly fine, but it becomes weird to me when people start trying to stigmatize a game that’s built around being accessible and bringing new people in. That doesn’t seem to say that a game is easy or hard. It just means that a game is welcoming. It makes sense that games on mobile would be welcoming, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they would be any harder or not.

When you say that the games coming out on the iPhone are straddling that line, I think it makes sense. When you’re developing a game for the iPhone, you’re looking at a potential audience of millions and millions of people. Way more people than exist on the Xbox and PlayStation and Nintendo added up. The mobile audience is so much bigger. It makes sense to build games that might convert new people, because new people are there.

If you make a game on the Xbox, there’s a legitimate cap of, say, 100 million people that can experience your game. That cap doesn’t exist on mobile. If you look at the download numbers on Pokemon Go, it’s way over 600 million people. What does it take to design a game that could appeal to that many people? If you’re putting a game into that environment, why wouldn’t you make it accessible and try to bring people in?

I can’t speak for you guys, but I think that’s what’s exciting about doing things on mobile. You’re not making a game that’s going into a niche. Every console game, every game you’d say is hardcore, that’s a niche game. It’s a game for gamers, hardcore gamers. I love those games. I’m in that niche. It’s a big niche, a big market. But when you make a game on mobile, you’re making a game that’s not for a niche. It’s for a huge contingent of the world. When you do something for that market, you need to build it in a way that’s accessible.

GamesBeat: If you could finish this sentence: “I wish Apple would…” What would that be?

Cash: I understand some of the hardware limitations, but it would be awesome to see haptic feedback on the iPad. I’m sure that’s not something they’re not thinking about, though.

Gage: I’d love to see Game Center come back even stronger than it is.

Cash: I agree with that as well.

Gage: It’s a big missed opportunity, to just see it sitting around.