An alien-infested space station isn’t the best place to question your life’s purpose. As Morgan Yu learns in Prey, the existential struggle is just as real as the deadly creatures lurking in the shadows.

Arkane Studios faced similar questions about identity (but with much less bloodshed) while making its sci-fi thriller. Out now on PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and PC, Prey is an action role-playing game where you have to fight an alien species known as the Typhon. It’s a premise we often see in pop culture, let alone in games. What makes Prey stand out is the story behind its development, where an unproven team resurrected a dormant franchise in a genre that’s difficult to master.

Arkane’s game is a reboot of the original Prey, a story-driven first-person shooter that Human Head Studios released in 2006. That company was working on a promising sequel until publisher Bethesda Softworks killed the project in 2014. Then after years of rumors, Prey resurfaced at last year’s Electronic Entertainment Expo tradeshow, where Bethesda unveiled a much different take on the franchise.

But aside from the name, Arkane’s game doesn’t share anything with Human Head’s sci-fi universe. According to lead designer Ricardo Bare, the core idea for Prey had been percolating at the studio ever since they finished the last of Dishonored’s add-on content in 2013.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

“Even before we had the name, we wanted to make a game like this: a game that takes place on a space station with aliens that has our signature Arkane-style game mechanics,” Bare said in an interview with GamesBeat. “The opportunity to use the name came afterwards.

“In fact, Arkane has made a game like this before. The first game that Arkane made was called Arx Fatalis, and it was structurally very similar to [2017] Prey. It was a fantasy game that took place underground in a dungeon. So we call the space station our ‘space dungeon’ now.”

Above: Arkane’s first game was Arx Fatalis.

The rise of Arkane Austin

Founded in 1999, Arkane consists of two teams: one group is in the headquarters in Lyon, France, and the other is in Austin, Texas. Bare, a veteran designer who previously worked at Ion Storm (Deus Ex) and Midway Games (Blacksite: Area 51), joined the U.S. branch in 2009. At the time, it only had a handful of people, including creative director Harvey Smith and Arkane founder Raphael Colantonio. It soon grew to around 20 employees.

But the majority of the company (more than 60 people) were in France. Both sides worked together on several games, with the developers frequently traveling back and forth between the two offices.

After Dishonored’s release in 2012, Arkane decided to split the team so it could work on multiple games at the same time. Lyon took charge of Dishonored 2, swelling in size to accommodate the sequel’s bigger ambitions and the arrival of the PS4 and Xbox One consoles. Austin underwent a similar transformation as it began working on the project that would later become Prey.

Above: Prey lead designer Ricardo Bare at GDC 2017.

“On the Austin side, we started to incubate this new IP [intellectual property], this new game, as well as expand the team massively,” said Bare. “We switched consoles, we got a new game engine, a new IP, and a brand new team all in the same dev cycle, which is kind of ridiculous.”

Though the Lyon team helped out from time to time, Prey was very much Austin’s baby. The U.S. team grew to 70 people over the course of development, many of whom were new to the company. While this hasn’t created any rivalries between the studios — Bare said they’re incredibly supportive of each other — it did add some pressure for the newcomers, who felt like they had to prove themselves to the folks in Lyon.

“They wanted to impress their Lyon colleagues by doing a really good job. … They wanted to show that they can make a compelling and beautiful world as Dunwall from Dishonored,” Bare said. “I think they did.”

A believable sci-fi world

Prey’s Morgan Yu is a scientist who is also the main test subject of a mysterious experiment. When the Typhon break loose, it’s up to Morgan to stop them — but the character isn’t your typical space marine badass. One big difference is that Yu is Asian, a rarity among gun-toting heroes in big game releases.

Arkane Austin turned to a lot of science fiction for inspiration. The team studied Solaris, Moon, and other films that explore what it’s like to be alone in space. Bare also read old stories from sci-fi author Robert Heinlein, such as “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress.”

“Me and some people on the team also just did a lot of actual scientific reading. Even though the game gets wild … we tried to at least start it at a place that was very grounded,” said Bare.

“So we did a lot of reading about neuroscience — learned a lot about the brain [laughs], which was super fun — a lot about the space technology industry. It’s really cool that we live in an age where this private space industry is happening.”

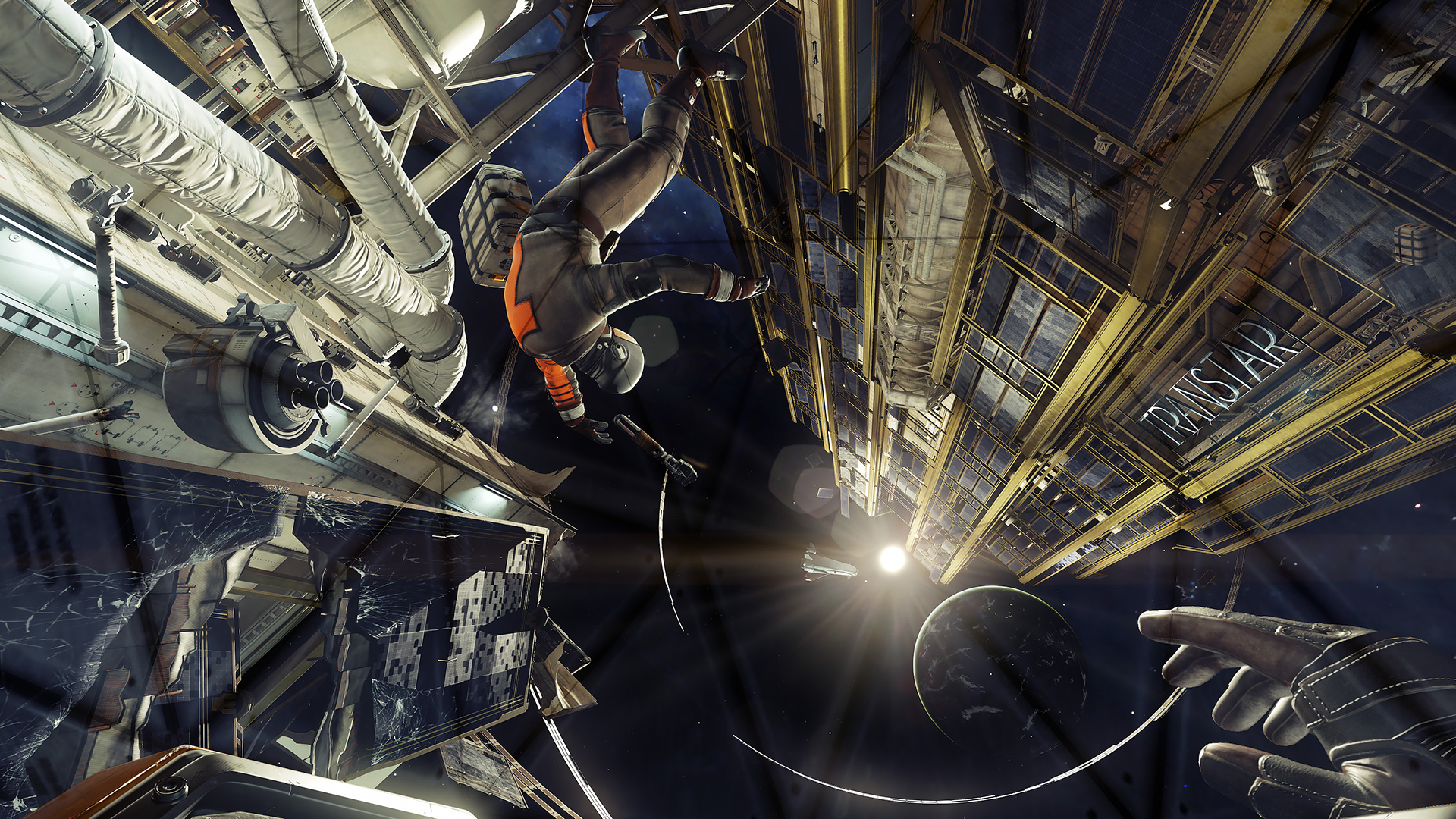

Above: The Talos I lobby.

Prey’s version of 2035 imagines what someone like SpaceX founder Elon Musk would’ve done had he started his ambitions earlier in history. In this alternate timeline, the Cold War space race led to the discovery of the Typhon and the construction of a large space station to contain it. Later, a powerful company called the TranStar Corporation takes over and transforms the vessel into the skyscraper-sized Talos I.

Another example of Prey’s grounded roots is the Neuromod, a tool that you use to learn the Typhon’s powers and enhance your human abilities (such as hacking computers or repairing equipment) by altering the chemistry of your brain. It’s loosely based on real-world experiments where scientists can manipulate neurons by making them sensitive to light.

But instead of lasers, Prey’s device uses needles. Big ones. To unlock the upgrades, you have to stick the Neuromod’s needles into your eyeball.

Above: Would you stab your eye just to get a few supernatural powers?

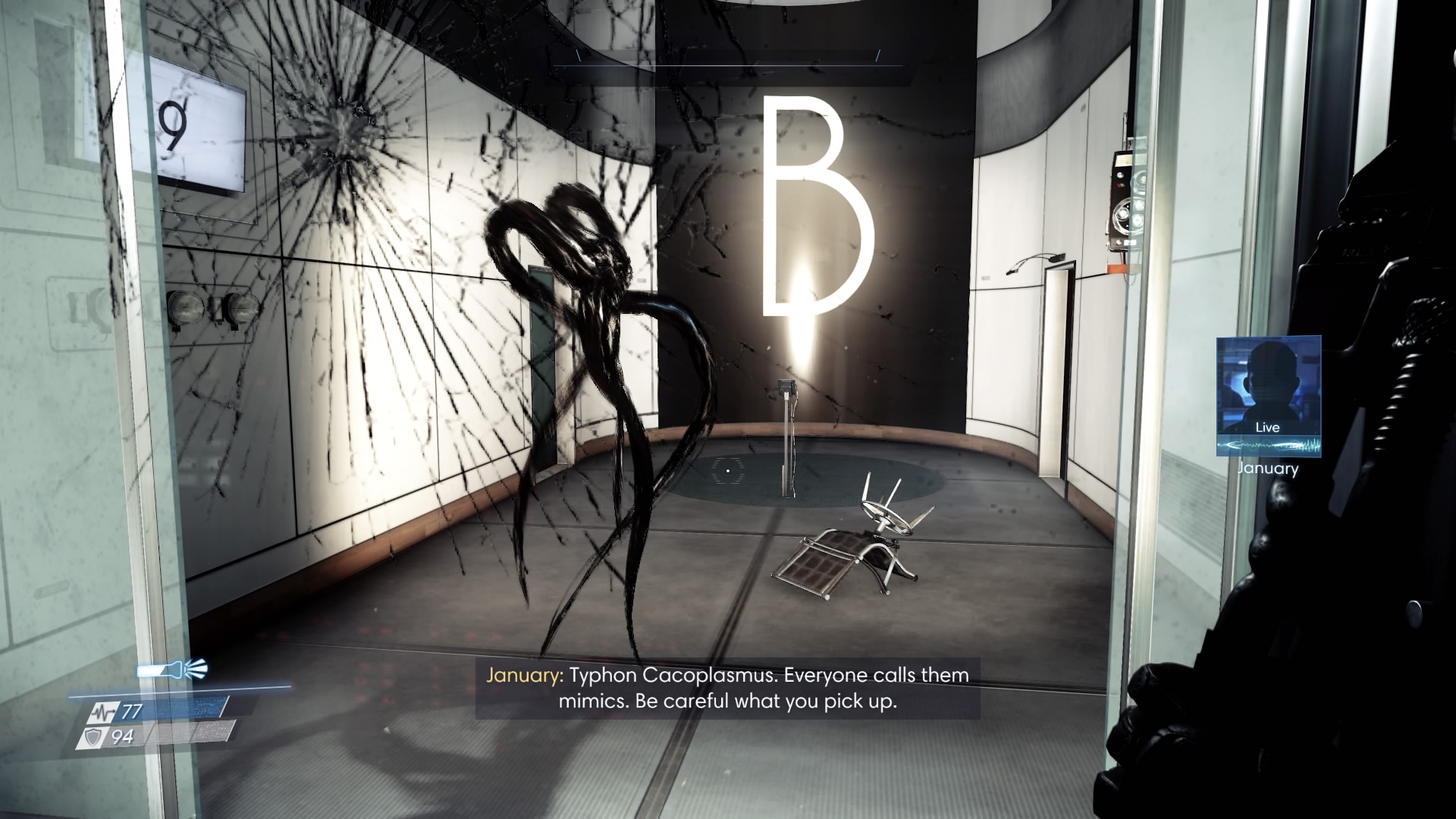

Like Dishonored, Prey encourages you to experiment with your weapons and powers. You can use the Typhon’s Mimic Matter — which transforms you into everyday objects — to possess one of the space station’s automated gun turrets or to hide from the aliens. With Lift Field, you can either launch your enemies high into the air or use it to propel yourself to hard-to-reach places.

The powers you collect can have consequences outside of combat as well. The turrets, for example, can be a valuable ally because they automatically target any aliens around them. But if you harvest too much Typhon DNA, they’ll turn on you. The other human survivors on Talos I will also react to you differently.

However, you can avoid that by simply not learning any of the alien abilities. It’s possible to finish the game without them.

Lessons from Dishonored

The mix of Typhon powers, tools, and conventional weapons offer a degree of freedom and flexibility that isn’t seen in many games. But that’s not a signature of Arkane’s treatment of Prey. These complex and unscripted interactions are an intrinsic part of immersive sims, which first emerged with PC classics like Ultima Underworld, Thief, and System Shock. The seminal System Shock series from Looking Glass Studios was a huge inspiration for Prey in terms of creating a tense sci-fi setting.

Though Arkane tried to make other types of games before, it keeps coming back to immersive sims. Everything in its catalog, from Arx Fatalis to Prey, have detailed worlds with interlocking mechanics that leave room for the player to improvise. The studio most recently demonstrated this with Dishonored and its sequel.

One of the lessons the Austin team learned from working on that series is the importance of easing players into these digital playgrounds, especially for those who haven’t tried an immersive sim before.

Above: Prey also takes you outside the space station.

“Unless the game invites players to do so, it’s not always obvious that [for example] you don’t have to find the key to this door,” said Bare. “You can look around and find an alternate way, or you could hack the door. Maybe you could blow the door up. I think lots of other games train players [to think], ‘There’s only one solution to this problem. And you have to try to discover what the designer had in mind.’

“Whereas we’re like, ‘No, there isn’t one solution. You can improvise a solution to this.’ You might be able to come up with something we don’t even know about because of all the systems interacting together. Part of the challenge is letting players know that it’s possible. That was challenging on Dishonored. And it’s still challenging on Prey. But we learned we have to present [those possibilities] to the player very early on.”

Yet Arkane didn’t want to overwhelm players with too much information. So the developers decided that for the first few hours, you’ll only have access to your human abilities. Eventually, the story introduces more nuanced tools like the Neuromods and the Psychoscope (a device that scans the different Typhon enemies for their powers and weaknesses).

Above: The Mimics can transform into different objects.

However, planning for what abilities a player might combine in any given situation (and thus rewarding them for their curiosity when it works) is an impossible task. The best Arkane can do is just spend a lot of time playing through the game to identify any interesting combos it should support.

“And the things that don’t [seem cool], we cut and get rid of,” explained Bare. “You know you’re in a good place when different people on the team are arguing about things like, ‘This power is the best!’ and ‘This other power is useless!’ And the other person is saying the opposite. … That means different people are finding different ways to play.”

Ideally, the goal is to make players feel like the only limit is their imagination.

“The best feeling is feeling like you’re playing a game where anything is possible, even if it isn’t literally true,” said Bare.

Above: The Typhon come in different shapes and sizes.

Creating a ‘sublime experience’

If you look through forum threads or YouTube videos about Prey, it’s clear some fans still mourn the loss of Human Head’s Prey 2. That put Arkane in an awkward place when it came to managing people’s expectations for the game.

“It’s tricky because, admittedly, the original Prey was a really interesting game. And the pitch and demo of [Prey 2] was cool, too,” said Bare.

But the designer reminded GamesBeat that the company really only makes one type of game: immersive sims. That specialization is one of the reasons he joined Arkane in the first place. It’s a genre few developers try to tackle.

“For one thing, [immersive sims] are really hard to make because they’re so complicated. But they’re also super rewarding, and they ask a lot of players,” said Bare. “If you’re playing a linear shooter where your instructions are just to keep moving forward and shoot everything that moves, that game doesn’t ask a lot of you, right? It doesn’t demand a lot of the player.

“But playing a game like Dishonored or Prey is a little bit like playing a musical instrument. The game asks a lot of you, but it also rewards you tremendously, more than the other kind of game that I’m talking about.”

Above: The GLOO gun traps the Typhon in a hardening foam.

From Arkane’s point of view, these types of games always have at least two things in common.

“They always have a strong sense of place — that’s where the ‘immersive’ part comes in the word immersive sim,” Bare added. “They always feel like a very cohesive, well-built world where you can look around and deduce the story of the place and [figure out] what happened. Everything has depth.

“It’s like an iceberg: You see the tip, but you know there’s so much more below the surface in terms of world-building. You believe that you’re in a real place. And the second part is those layered, super-rich game mechanics, which just translate to the player feeling like, ‘I can do anything in this world. There are these rules and systems, and I can understand them and make a plan. And when it works, I feel this magical, almost sublime experience.’”

The new Prey can never live up to the promise of the cancelled Prey 2. Instead, Arkane is carving a new identity for the beleaguered franchise (whose origins actually stretch back to 1995), one that builds on the beloved immersive sims that came before it. If the reboot is successful, it’ll further cement the studio as a top-tier developer — and maybe even give the Austin team something to brag about to the Lyon office.

As for why they chose to use the Prey name, Bare said the reason was simple: It’s a great title for a video game, and “naming video games is hard.”