Presented by Intel — “I have AR mania. I have the VR madness.” While consumer virtual reality headsets are still nascent, they are just the latest phase in VR’s history. For 25 years, Schell Games founder Jesse Schell has been part of that history, immersing himself in virtual worlds. And teaching people about them, too.

“I started doing VR experiences in 1992, and I’ve done them more or less continuously since that point. I did them all through graduate school, I went to Disney where I was creative director at the Disney virtual reality studio where we built Disney Quest, and when I started teaching at Carnegie Mellon in 2002, I started teaching a virtual worlds class — I’ve been building VR worlds this whole time. So when VR finally came into the market, I was like, ‘Yes! Let’s do this! I’m ready!’”

VR and AR, then, are important focal points for Schell Games and its 110 staff, but Schell is a big believer in diversity’s ability to make a company stronger and thus doesn’t like to put the studio in a box. So the studio makes VR and AR games, but it also develops games for other platforms too. Similarly, any genre is fair game, from I Expect You To Die’s espionage and escape room conceit, to Enemy Mind, a pixel-art, side-scrolling space shooter. Educational games are a favorite, though.

“We do lean towards things that are a little more family-friendly,” Schell says, “but there isn’t one genre. Everyone loves Shigeru Miyamoto, and if you look at what connects all of his games, they’re generally connected by the aesthetic. The game mechanics might be different, but the aesthetic is the same. I find myself resonating much more with a different Japanese designer: Yu Suzuki. He worked on Space Harrier, Hang-On, Shenmue — all these games that don’t have anything to do with each other, except that each one is really innovative in a new way.”

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Once a year, in November, Schell Games’ devs put everything on hold and embark on a week-long game jam — a week of passion projects and experiments. A lot of these projects end up being learning experiences, but sometimes they grow into full games like Orion Trail. It’s a mash-up of games like Oregon Trail and Star Trek: Bridge Commander, putting players in the captain’s seat of a spaceship. A VR version was also eventually developed.

Schell stakes VR’s future on kids

VR is increasingly finding a niche at the intersection between education and entertainment, and it’s a place where Schell Games has been doing some exploring.

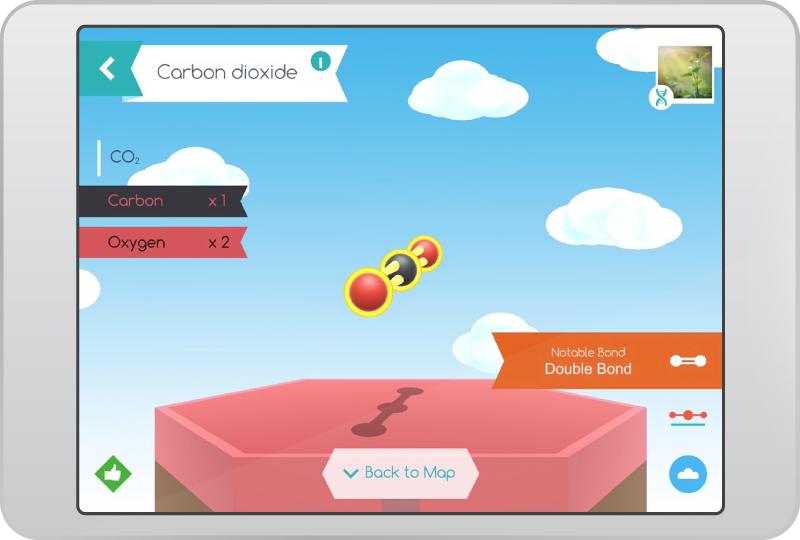

“There are things that VR is good at teaching that are hard to teach in other ways,” Schell explains. “Our first real project in that direction is called SuperChem, which is a virtual reality chemistry lab. It’s great for schools because a chemistry lab is a thing that has a lot of danger like broken glass and spilled chemicals. It also has a lot of expenses because you have to dispose of all these chemicals that you have to buy every time you use it. And since you have to be safe, everything has to go super slowly. By making it all virtual, you set aside a lot of that expense, and kids can do things much faster.”

There are two versions of SuperChem — the virtual lab for schools and SuperChem VR, a space adventure game that tasks players with using real chemistry to avert a disaster on a space station. The game’s not just an educational tool, then, but also an adventure game that can stand on its own. Schell uses Kerbal Space Program as an example of another game that straddles that line. It’s undoubtedly educational, but it’s also a huge commercial success on Steam.

Schools will eventually get VR headsets just like they get computers now, thinks Schell. He imagines it going down the same path — some enthusiastic teachers getting a single headset for the school, impressing people, eventually growing that into a lab with multiple devices and classes that both employ them and teach kids how to use them. But as for these sorts of things becoming commonplace? 2035 is Schell’s guess. By then AR and VR will be combined in discrete, lightweight glasses, and it will be the kids that drive adoption.

Happy Atoms is another chemistry game that’s been designed with education in mind. There are two parts to it: a physical element, with big atoms that can be built into molecules, and software that can identify what a child has built. “I don’t know how to make these sorts of physical things,” Schell admits, so he partnered with Thames & Kosmos, a science kit producer, which helped with the production of the physical components and bringing it to retail.

“AR is best as a child’s medium,” he continues. “Adults are uncomfortable about having an invisible person standing next to them and talking to them, or running around outside, chasing a virtual ball. But for children, that’s fine, they have no problem with that. So in the mid-2030s, I think we’ll see children embracing these magical glasses. It’s going to combine with AI. By that time, we’ll have some pretty great AIs, and the idea that you can have an imaginary friend for your child, who is kind of omniscient and can teach them all the right things at all the right times, is going to be very appealing.”

Moore’s Law at work

Though he predicts some big leaps, it’s nothing Schell hasn’t already seen in the VR space. And while there are plenty of technological hurdles, the biggest ones are things like cost and accessibility, both of which have changed dramatically in the last couple of decades.

“If you look at the specs for the Oculus Rift DK2, they’re almost identical to what we had for Disney Quest in 1995, but they cost literally 1000 times less. The original systems that we put into Disney World were Onyx supercomputers, these giant purple refrigerators with custom made headsets and these $100,000 magnetic tracking systems. All told, the system cost $500,000. So when the Oculus Rift was first announced, we realized the specs were just about what we had back then, but for so much less. It’s Moore’s Law hard at work.”

Here, at the end of 2017, Schell and his studio are still exploring the best ways to take advantage of VR, what types of games and experiences work best, and what feels best. Touch is as important a sense as sight or sound, but not something games typically take advantage of. Touch screens have changed how people interact with technology, but less so in gaming, outside of mobile. VR, however, is all about intimate interactions and manipulating the environment. Haptic feedback is one way to enhance that, but physical components are another route — one which Schell Games has gone down.

“Our mission statement is fairly simple,” Schell says. “We like to make experiences we’re proud of with people we like in order to make the world a better place.”

Sponsored posts are content produced by a company that is either paying for the post or has a business relationship with VentureBeat, and they’re always clearly marked. Content produced by our editorial team is never influenced by advertisers or sponsors in any way. For more information, contact sales@venturebeat.com.