Joseph Fares and David Cage are game directors who love storytelling. They have created memorable games that players rave about. But they share little in common in how they approach creating their games.

We discovered this in a fireside chat at the Gamelab event last week in Barcelona. I moderated a talk between Fares, founder of Hazelight in Sweden and famous for saying “fuck the Oscars” on The Game Awards, and Cage, cofounder of Quantic Dream and builder of games like Heavy Rain, Beyond: Two Souls, and Detroit: Become Human.

Fares wants to get away from the purely passive watching of film and take advantage of the unique interactivity of video games. So he makes a point of focusing on gameplay patterns and the concept for a game first, rather than on storytelling. By contrast, Cage said he always starts with emotion first, and what he wants to say in a game. He writes a script and then thinks about the gameplay later.

In his most recent game, Detroit, Cage included many options for different endings. But Fares always had in mind just two different endings and a mostly linear narrative for A Way Out. We talked about these differences and wondered what was the best way to blend these techniques in a game with a good story.

These different approaches reflect the core tension in games between story and interactivity. A game could also be on rails, or give players all of the choices they can make in an open world.

“What is fascinating to me about games is that we create something together [with the players],” Cage said.

Here’s an edited transcript of our panel.

Above: Josef Fares, creator of A Way Out and Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons.

GamesBeat: Do you want to describe how you start making a game, Josef?

Josef Fares: It’s interesting. We have very different approaches to some things, but others are quite similar. It’s just the way we work. For me, I approach — every game I think about is about the game mechanic first, and the game concept itself. Then, from that — there is a story arc, but from that I go and find the game. I’m super curious about the interactivity in a game, how to create a game mechanic that almost dances with the story. It’s part of the story. That’s something that both in Brothers, A Way Out, and our next game, we’re trying to push even further. That’s the way I approach a game from the get-go.

David Cage: My approach is to start — there’s no rule. Sometimes it starts with an emotion. Sometimes it starts with an idea or a moment. On Heavy Rain, the game started with something that happened to me when I lost my son, my six-year-old boy, in a mall. I was so scared. I was curious to see if I could create that impression, that fear, in a game, an interactive experience.

Detroit started based on a book called The Singularity is Near by Ray Kurzweil, which is about this idea that one day there could be machines that are more intelligent than we are. I had this image, for whatever reason, that we would have an android assistant who’d go shopping with us and carry our bags. But at one point we’d go in a restaurant and these androids would wait outside. I had this image of a row of machines looking exactly like people who wouldn’t be allowed to go in the restaurant. I thought, “What if I was in the shoes of one of these androids? What if I thought this was unfair?”

That was the starting point of the story. I started pulling strings and trying to see what stories came with that. But in a nutshell, the most important thing for me is what people feel during the experience. It’s all about emotion. Of course it’s very important what you do, what buttons you press. All of this is key. It’s a way to be immersed in the world. It’s a key component. But at the same time, my experience is that people remember not so much what they did. They remember much more how they felt. If you think of the best games that you’ve played, probably you more remember those strong emotional moments and the turning points in the story than the buttons you pressed. That’s why I focus on that beyond anything.

GamesBeat: Do we have a basic tension here between story and interactivity?

Fares: I would say yes, but in a good way. I would argue — I agree with what David is saying, but I think it might be because my background is as a filmmaker. I tend to try to get away from that as much as possible. I do agree with David that emotions are very important, but I also believe that there’s something unique to the storytelling in video games. The medium itself, the interactivity itself, connected to the game mechanics — for me it’s not just pushing a button.

Let’s say I make a game about love, or about an alcoholic parent. If I can make it feel that you’re in control of that, make you feel responsible — when you’re much less passive in a game, much more interactive, it’s a more emotional, powerful impact. That’s unique to games.

GamesBeat: There’s a good scene in Red Dead Redemption 2 where you play a drunk person wandering a saloon, trying to find somebody. Every person you see is an illusion and you’re trying to find someone real among them. That’s a good scene to you?

Fares: That’s a good scene to me. The game was a bit too long, but that’s another discussion. I think games are too long in general. But I don’t think we have the time.

Cage: To me what’s unique is the fact that video games are the only medium in which you create something with your audience. If you’re a filmmaker you create something on their own and you show it to people. They can emotionally react to it, but they can’t change the content. What’s fascinating with games is that we create something together. In Detroit I tell a story with millions of people I’ve never met. This is the most fascinating thing when you think about it. It’s unique to interactivity.

I agree with what Josef said about the importance of controls. The sense of mimicry, the fact that you feel in the shoes of the characters. Sometimes playing with the erosion of controls, what we were talking about with having to bend your arms — if you do it mechanically it’s a sense of mimicry. It makes you feel like you’re the character. It awakens something in you. Maybe if you did that one day in your life, it’ll remind you emotionally of this moment, because you’re doing it physically.

Being drunk is a good example. We call that erosion of control, the fact that you have a hard time controlling your character. There are many tricks you can play like this that will reinforce involvement and immersion in the story, but also emotional involvement in the experience.

Above: David Cage of Quantic Dream, creator of Heavy Rain, Beyond: Two Souls, and Detroit: Become Human.

GamesBeat: Solving the tension results in some very different kinds of games, this tension between story and interactivity. Are there certain kinds of games you would put on one end of this spectrum or the other? Is it a difference between a game on rails versus an open world?

Fares: The thing is, both games should exist. But if you ask me, I’m more the type of guy that likes more linear experiences. You have open world games today — this year I played Assassin’s Creed, Red Dead, Days Gone, and Spider-Man. I liked the Spider-Man game the most, actually, because it wasn’t too long. But I finished all of them. The problem with open world games that they tend to end up in a situation where you have to copy and paste design, which makes me lose the story. For that I do enjoy the linear type of games more — The Last of Us or Journey. That gives me an experience I can follow from beginning to end.

With that said, that doesn’t mean that games like Detroit, which I also played and finished, I don’t find enjoyable. I did enjoy it. However, what I fear this industry is going toward — “linear” and “rails” seem to be said in a negative tone, which I don’t like. I think it’s stupid to say that. Both games should exist. Not everyone — sure, I do agree that choices are part of video gaming. But choice is something we’re seeing in movies, like they’re testing on Netflix. That’s not unique to gaming. Both should exist — being able to choose, but also being able to follow a story.

As David said, it’s about being emotionally attached and emotionally touched by a game. If we look at a great movie, you’ll be emotionally touched. A choice wouldn’t necessarily make that emotion stronger. It could make it stronger, but it could also make it weaker. That’s why I think both games should exist. But I do hear the negativity about “on rails,” which I don’t like. It’s the opposite of what I’d say. Games are supposed to have so many choices now, to be so open, that it becomes confusing sometimes.

I’d love to make an open world in the future, but let me tell you, it’ll be very different. I’d rather do an open world that’s maybe a 10-hour experience, and the world is full of content that’s super unique and different, rather than having to repeat myself. You can lose the story in an open world. That’s why I enjoyed Spider-Man, which is more of a shorter, focused experience.

Cage: There are many different ways of telling an interactive story, I think. I don’t think there’s a right one and a wrong one. There are different games telling different types of stories in different ways. What you’ll get naturally from an open world, for example, from what you’ll get from a game on rails, from a game like Detroit that’s really an interactive drama where your choices matter. There are different games for different audiences, and I think that’s absolutely fine.

Even technically, as a matter of structure, there are different ways of putting this together. Many action games these days make the choice of having an action scene, a cutscene, and an action scene. Splitting the story and the action into two parts, which is one way of doing it, and there’s nothing wrong with that. We took a different direction in Detroit where we chose to put you in the shoes of the characters, let you make the decisions, and let you face the consequences of your decisions.

For that’s something important. I think that the choice makes the experience emotionally stronger when the choice is relevant, when it’s emotional, when you can relate to the choice of what’s going on. Just a choice of whether you want to open the left door or the right door, no one cares. But if it’s something emotionally involving, it becomes important. Then I think it takes on another dimension than, for example, a story where the characters make decisions and you can agree or disagree, but you can’t change what’s going on.

Here, you tell the story. The story is told through your choices. You feel emotionally responsible for the characters. That’s what I like about it.

Above: Quantic Dream’s Detroit: Become Human pushed the edge on face animation.

GamesBeat: For Detroit, how many endings could you have had? In your last game, you could have two endings.

Fares: The two endings — that was the whole game concept. I’d like to have one ending, really.

Cage: We could never exactly count them, how many endings there were to Detroit. [laughs] It wasn’t about the endings. It was about having different paths leading to them. The journey itself is different. Different characters can be present or be dead or make different moral choices or be in different situations at the end.

You take a character like Marcus, who starts this revolution, for example. He has different paths. He can become a violent character who leads a violent revolution, or a pacifist character. There are many other choices in the game.

GamesBeat: Would it bother you or your team if players only choice maybe one or two of the branches and never played all of the rest?

Cage: No, that’s absolutely fine. That’s part of the concept. We tried to have choices that are balanced. If you have a choice where you have 0 percent or 10 percent of the people making it, it’s not really an interesting choice. It means the dilemma wasn’t really there. We love choices when it’s really 50-50, depending on your moral values and who you are. You can project yourself into the choice and think about what you’d do if it was happening to you. That’s the kind of choice we like. We have a balance that’s usually about 50-50, 40-60, sometimes 30-70 max. But what we realized is the very positive impact it had on the community and on the sales of the game.

Let me give you an example. In the past, YouTubers for example were kind of a problem for us. People were showing the game and players would watch the videos and think, “Okay, I get the story. I don’t need to play the game. I know what it’s about.” With Detroit we saw the opposite happening. They were showing one playthrough, but they couldn’t show everything happening, all the branches. Players watching it thought, “I wish he’d done this. I’ll play the game to see what would happen with my own choices.” Suddenly they became our allies and helped us promote the game.

But in general what I love the most is hearing two people talk about the experience. “Did you see this? Did you see that? This character died there.” “What? No!” They compare their playthroughs and realize how different they are. That’s what I prefer. Some players may think that their story was linear, because the story they had was the story they were supposed to have. It’s about explaining, no, your story is what it is because you played it that way, but it could have been very different.

GamesBeat: Part of why this is a fun discussion because of what could change in the future. You brought up YouTube. In some games now, like Mixer [or Twitch] games, they encourage the developer to take into account the audience for streamers and whether they get a say in how the game is going to proceed. They can drop in a bunch of power-ups for the player at a certain stage in the game when they’re struggling, for example. You get audience participation in the story of your game. Things like this could happen and change the way you make games.

Fares: Yeah, it could, but for me I’m not really a big fan of it. I do think that sometimes developers — too many times they wonder what the players want, the player community. I almost compare it to a relationship. If you’re in a relationship and you’re always asking your partner, “What can I do for you?” you get tired of that. You need a fluid give and take. I love my players, but they should also respect me and trust me, trust the vision I bring to the game.

From a story perspective it’s important to have a clear vision and stick with it and trust it. I know my decisions — I don’t know what experiences David has had, but from my two games so far, if I had based my decisions on what the community would say or what people think they want to play, those two games would have been impossible. So I do trust myself more.

Cage: There are two quick things. First, I’m curious about crowd play. We had something not exactly like that in Detroit, but we could see some YouTubers playing the game and having the people posting in real time what they’d like to see the player do. That was very intriguing. Yes, I’m working on single-player games, but there’s something very intriguing in this concept that the community can drive the story in a certain way.

I was very surprised, traveling to China, when I realized that many people watched the game on the local video sites. They were commenting on it live. You could see the video with the stream filled with text passing by in Chinese. I couldn’t read it, but I hope they were saying nice things. [laughs] But they were all watching the game and commenting on it.

GamesBeat: You mentioned that most people played Detroit socially.

Cage: There’s a very social component to the game. Many people played the game with their boyfriends or girlfriends, the same way they’d watch a TV series or a film together, except they can change the content. It’s become a joke now. Every time someone comes to me and says they played the game and liked it, I’ll ask if they played with their wife or husband, and they say, “How do you know?” I know because everybody did. It’s very popular to play this type of game this way. I really like that.

There are different ways you can consider your job when you’re a creative person. Either you receive a marketing brief telling you all the boxes that you need to tick — do this, do that — because that’s what was successful last year. This is what you need to do to be successful. That’s one way of doing games, and I respect that. But I think that if you want to be a creative person in this industry, you need to think about what people will like four years from now, not what they liked last year.

It’s a different approach. It’s about taking risks. It’s about going where maybe people don’t want you to go right now. Maybe they don’t believe in what you’re doing. That’s fine. Our work is about taking risks.

Above: Leo (left) and Vincent have to rely on each other in A Way Out.

Fares: I say something similar very often. I’d like to make games that players don’t think they’re going to like, don’t know that they’re going to like, but they like it. That’s the surprising element. “I didn’t expect to like this game!”

To what you said before about the YouTube community, A Way Out is linear. It has some choices, but those choices are based on different gameplay scenarios. They don’t affect the story. They affect more of the gameplay, because I’m more interested in that. But when it came out, a small game like A Way out, still an indie title, it was number one on Twitch. I thought, “Oh shit, we’re fucked. Everybody knows the ending now. That’s it.” But then they told me it sold really well. People saw the game and wanted to play it.

But in A Way Out’s case, it was because people wanted to experience the game with someone who hadn’t seen it on Twitch. That worked out for us. It was a co-op game, so you could play it together with someone. The fun part is that something happens very unexpectedly at the end. I like to mindfuck with the players. There’s a moment in Brothers, A Way Out, and in the next game as well….

GamesBeat: You’re the puppet master, toying with the players.

Fares: Yeah, making them double-take. I remember I told one of my designers that we were doing this scene in the next game. “When people see this they’re gonna shit themselves. I want them to go totally nuts.” Like we want to deliver the game with a couple of diapers. [laughs] That’s my goal, every day. Fuck it up, fuck it up. Let’s do some crazy stuff. The next games are going to be crazy.

Cage: Sometimes I think that Josef goes too far. [laughs]

Fares: That’s what I like about this. I do think the more we talk about this, we have different approaches, I would say, but you don’t feel we do. I feel like I’m way more interested in interactivity. I think we have a different approach on this.

Above: A Way Out comes out on March 22 on Xbox One, PS4, and PCon Origin.

GamesBeat: I think one difference is that you want to put gameplay into almost everything the player does.

Fares: Yes, yes.

GamesBeat: Every choice that happens. You’d ask David, “Why can’t this choice somehow involve the player doing something?”

Fares: I just said that to David yesterday. I’ve played all of his games and I really enjoy them, but sometimes I think, “There could be more to this.” I don’t think I would change anything —

GamesBeat: You had this example of rocking the baby.

Cage: It’s funny, because this something we work on a lot. How do we make daily life playable? That’s what we have in mind. Giving you a gun and shooting at people is one definition of gameplay. I don’t think it’s the only one. You can have different ways of interaction.

In Heavy Rain you had this baby in your arms and you needed to rock it. We always want to play with this kind of thing. How do we make things playable? We have this theory we call the sense of mimicry. How do we make you mimic, with your controller, what your character does on the screen? We developed this approach where you actually unfold — you really control the arm of the character. Even picking up a glass is something you actually do.

Making daily life playable is something interesting, because suddenly you’re not limited to the stories you tell with zombies and wars. You don’t need to be a soldier or kill people. You can play anything. You can play a tragedy or a comedy, anything happening in real life.

I had a discussion today with someone who asked me why we don’t have more dramas, more things like Mad Men, the type of TV show where nothing spectacular happens. Why are games always focused on big physical things, where weapons and violence are involved? Can’t we create a game that wouldn’t be about that? This person was so right. Yes, let’s create games that aren’t about violence, that aren’t about killing people. There are games like that out there, of course, but let’s create more. This is an interesting way to develop in this industry.

GamesBeat: Maybe you would want to be able to, say, throw the glass in the fireplace. A bit more interactivity, a bit more control for the player.

Fares: I do agree with what you’re saying now, though. It’s a very good point. That’s what triggers me now. I’d like at some point to make a love story, but make it really playable and interactive. Imagine making a sex scene, a really nice one, playable. [laughs] In a beautiful, emotional way, you know what I mean? Imagine if you could do that. In the future, who knows? Really getting an emotional connection to something. There’s something very exciting about this.

I do agree with what David talked about yesterday as well. How can Nathan Drake kill so many people and still be this charming guy? He’s murdering a couple of thousand people. It’s weird. It would be interesting to — I believe that gameplay could be — I don’t always like to use the word “fun.” But it could be fun to just chop up a cucumber for a while and then go do something else. Gameplay is definitely not necessarily about shooting and fighting and stuff like that. That’s all something that can be unique to games, and I believe it’s super exciting. Especially in storytelling. If you’re doing a multiplayer game, a competitive game, you don’t want to cut up cucumbers.

Above: A rogue Android kidnaps a girl in Detroit: Become Human.

Cage: Especially not in a sex scene. [laughs]

Fares: It doesn’t have to be a sex scene. I’m talking about a love story, something emotional.

Cage: A love scene with cucumbers?

Fares: I mean, love is not about sex, you know? Or it is, also, but — you know what I mean.

GamesBeat: I was wondering about Minecraft. It’s a very popular game, but the story is what the player is making. Do you like a game like that or not?

Fares: Again, I don’t dislike any game. I think all games should exist. What I don’t like is that the industry and community and players and reviewers and journalists have decided that one thing should be good and this other thing should be not good. Minecraft is great. It’s fantastic that people can create their own content, create their own worlds. It’s obviously something that people want to do. Personally I don’t play Minecraft. But that’s me.

Cage: Josef’s right. There are different games for different people and different expectations. Sometimes you want a great story and sometimes you don’t. I don’t believe we should have stories in every single game. Sometimes it doesn’t matter. Even having some narrative dissonance, where you’re a serial killer and then you make jokes, in some games who cares? It’s not the point. But there are some games where you’re serious about storytelling and you think, “This is what is strong about my title. It’s the story.” Then you need to pay attention to narrative dissonance.

Again, I think it’s an open discussion. It’s great that there are different games for different people with different approaches to storytelling.

GamesBeat: Back to technology, David, you put a huge emphasis on visual quality and realism of human faces. It’s going to get easier for you to make those things much more realistic. But do you want to go there? How far along toward that realism do you want to go?

Cage: Photorealism isn’t a goal by itself. It’s just a type of rendering to corresponds to the stories I had to tell at the time. I’m not saying this is an ultimate goal and all games should be realistic. It just worked well with Heavy Rain, with the type of realistic stories I wanted to tell.

I don’t necessarily think it’s going to get easier with technology. I think it actually becomes harder and harder. Now you need to develop raytracing. You need to develop muscle systems and things like that in order to re-create a human being. In the past, you had maybe 80 polygons and you had to make a human being with them. That was a challenge. But it was something you could handle. Now it’s become so complex. The closer you get to realism, the harder it gets to handle the extra details that make it more and more realistic. It becomes more and more challenging.

Honestly, everything we’re learning is very interesting, about lighting and animation and directing actors. I wish we could one day reinject what we’ve learned about realistic rendering into non-realistic things.

Fares: I’m not really in a place where I can use photorealism right now, economically. It’s better now. I always call us more like triple-I, double-I, something like that. But I don’t think I can afford to spend the time to do something similar. I believe that your faces are amazing. If you look at Naughty Dog and those guys, they’re doing some really impressive things. But as you say, the more realism, the more work, and the more uncanny valley things pop up. It’s much harder.

Cage: And it’s not necessary to achieve emotion. You can have a cube that’s incredibly expressive if it’s animated the right way and it’s telling you something interesting. Look at Pixar. They’re not doing realism, but they make films with stories that are incredibly moving and very convincing. It’s not a goal, not a necessity.

Above: In A Way Out players had to work together with two controllers to play the game.

GamesBeat: If you look at some of the storytelling games out there, what are some things you admire? That’s one question. The second one is, if you looked at the competition last year for the award shows, it was between God of War and Red Dead. Even though they were both very well-done, God of War won almost every single time. Do you think there’s a reason for that?

Fares: Like I told you, I play all the games out there. Personally, my game of the year was actually Spider-Man. That doesn’t necessarily say I didn’t like God of War. I think God of War was a great game. But for me, I connected more with Spider-Man in some way.

The reason why God of War won and not Red Dead, I do believe it’s because God of War took some risks that were really cool. Cory and the team did something amazing. I give credit of course to Cory and the team, but also to Sony for taking a very well-known IP and totally going a different way. That’s cocky and that’s risky for a triple-A title, and I think it really deserved to win. I feel like that’s the reason why.

When Rockstar did Red Dead 2, it’s a great game in many ways. A bit too long if you ask me, a bit too repetitive in the mission design. You’d go out and shoot something and go back. I think that’s one of the reasons God of War won.

As far as games I admire, again, I’m very allergic to repetitiveness in game mechanics. I felt that both God of War and Red Dead were a bit too long. I needed a shorter experience. I think that’s why I was a bit more invested into Spider-Man. Especially with Red Dead, that locks me out after a while. It was so long! Who has the time for that? I don’t even have kids. I imagine for you — could you even play the game? Who finishes these games today?

That’s another thing we should talk about. If you look at — people are saying to me, “Oh man, A Way Out, 50 percent of players finished your game!” I should be happy about this? Are you fucking crazy? It’s like making a movie and half the people walk out of the cinema! We have a serious problem with people not even finishing our games, and still people are saying — if somebody talks to me about replayability, I’ll slap them in the head. [laughs] We should focus on having a great experience first. This just fires me up.

Cage: It’s an interesting question. Very few people realize that it’s between 25 and 30 percent of people completing a game that they started. As Josef said, it’s as if in the cinema people leave in the middle of the film, which is a bad thing. On Heavy Rain we had 78 percent of people completing, and similar with Detroit. It’s just the story. People want to know what can happen next. A story can achieve this for you.

What’s interesting with Detroit is we managed to make people replay the story to see all the different branches, which is quite rare in a narrative game. It’s because we showed the branches and all the variations and the story. That’s something important.

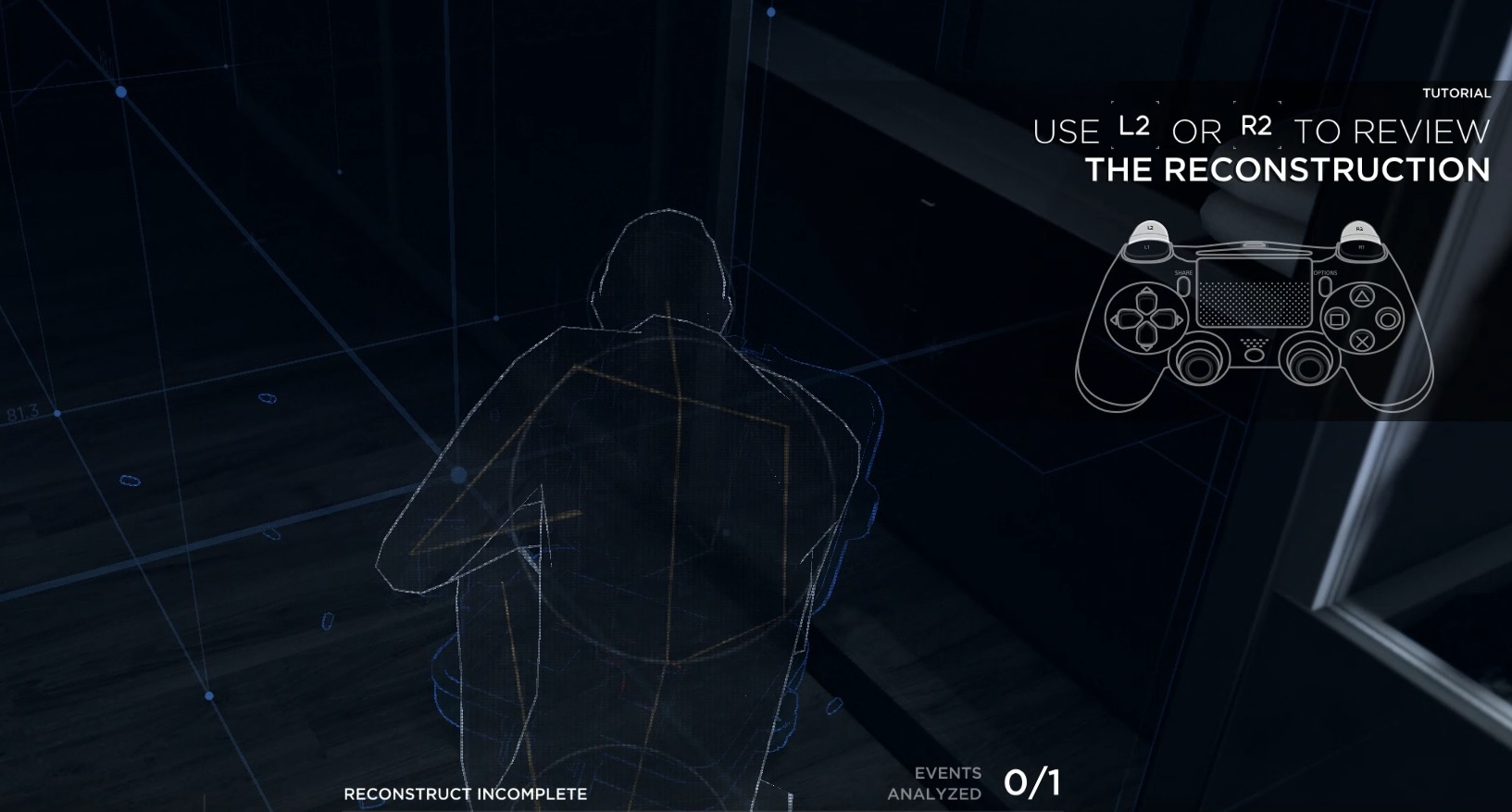

Above: Connor can visualize what happened at a crime scene in Detroit: Become Human.

GamesBeat: I don’t think I’ve come across another game that showed the flowchart of all the branches.

Cage: It’s been a difficult choice. There’s a small story behind this. We were working on Heavy Rain, and on Heavy Rain we had these playtests before we released the game. We did playtests with dozens of people a month to get feedback. We had this spectacular chase where the cop is chasing a suspect. The chase started in the streets. Then there was a covered market and then there was a cold room. It was a three act chase, very spectacular, a lot of special effects, very breathtaking.

There was this guy testing the chase. He lost in the first section, lost control, and he stopped in the street. But because the game had no game over, the story didn’t stop. He had to go back. The story continued, and then we asked him, “What did you think? How did you do in the scene?” He said, “Oh, I did great.” “You didn’t feel that you lost something?” “No, I was supposed to follow the guy, but he was supposed to escape anyway, and so I played well.” We realized that we had spent so much time developing all of this chase for the guy to just assume the game was linear, when there were actually so many branches.

On Detroit we remembered this story. We thought about what we could do to make sure people would know all the things behind the curtains. I’m usually the kind of guy who likes to hide what’s behind the curtain. On Beyond even the interface was invisible. The choices were invisible. Everything was organic. It was beautiful. But you know what? No one knew all the choices that were there. Then you think maybe that’s not the right decision. Maybe hiding everything from the player is not a good thing.

Detroit, to me, was a better compromise. It was about showing part of what you missed, so you understand it’s there. It played a major role in the success of the game. We got incredible feedback from the community about that.

Above: Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons won many Game of the Year awards.

Fares: It stressed me out a little bit. When I saw that, I thought, “Oh, shit! Now I have to replay it now! Shit, I missed this thing!” I got stressed out. But I’ll replay it to see how different it is. That’s always something that stresses me out. I know, from being a developer — I think, “Oh my God, that’s so much content.” You told me yesterday that there were 4,000 pages. That was insane.

GamesBeat: I think of the poor artists that did all the branches nobody sees.

Cage: We tried to make sure that at least 30 percent of the players saw any given branch, and that’s pretty much the statistics we have. And there’s not one artist working on all the branches that no one will see. [laughs] He would be pretty depressed. But no, everybody worked on everything.

As far as games that inspire me with their storytelling, the older I get, the more I’m inspired by life and emotions and what I experience in the real world. I try to translate that into games. When you’re a young writer you tend to re-create what you liked, the games or the films. Like everyone else, this is what I did when I started. Fahrenheit was inspired by many things, and Heavy Rain as well. Beyond a little bit less, and hopefully Detroit a little bit less. I guess that getting older and trying to do better at what you’re doing is trying to find your own voice, what you have to say that is you, and not borrowing from someone else.

GamesBeat: There is one worrisome direction where games are going, where with free-to-play and mobile games, the whole point is really just to stretch everything out, so that the player comes back every day and gets monetized more. If you have a game that’s going to last four or five years, that’s better than a game that you can finish after 100 hours of gameplay. These kinds of games are generating so much revenue sometimes that the publishers are looking at that and saying, “That’s what we need more of.” Does that seem like a bad thing?

Cage: Something tells me that Josef’s not happy about this.

Fares: I hate it. No, I don’t hate it. It’s just — hopefully — I do believe that there are enough gamers out there who love games, who’ll buy games, and who’ll make sure that the publishers understand that these types of games are needed. I’m talking about games like Detroit, like God of War, like Red Dead, like Spider-Man, like Assassin’s Creed. That’s a huge community, to be sure.

There are some worrying trends, but I do believe that the free-to-play market will drop soon. You have something like Apex that’s super well-marketed, but then it drops down. It’s hard to make free-to-play games. Everybody’s fighting for people’s playing time. I don’t know. I just believe that a really great single-player experience, a really great game, will never disappear. There are enough gamers out there who love them.

For me, I know that they say when you get older you’ll maybe stop playing, but that’s not possible. If I come to an apartment and I see there’s no console or PC, I think, “Don’t you have a toilet in here?” It feels like something is missing. I sometimes look at historical movies and think, “How the fuck did they survive without video games?” I love to play that much. I hope and believe that will prevail. We’ll never be able to not play something like The Last of Us. I think we’ll always want.

I think that will adjust itself. If you look at the mobile industry, it’s super big and it’s made a lot of money, but it still hasn’t taken over the console gaming market. There will be two different branches, I’d say.

Cage: I’m happy with all games. What I love about games is their diversity, the fact that there are different styles of games for different people and different moments in your day and your life. I play some free-to-play games and I really enjoy them.

Above: A father looks for his son in Heavy Rain

Fares: [laughs] What, do you mean you play Candy Crush and all that?

Cage: No, I don’t play Candy Crush. I play Hearthstone, for example.

Fares: Okay, I’ve heard that was good. I was just at a speech from this company called King. They were talking about creativity. I’m like, “What? Are you serious?” [Audience cracks up] I don’t have anything against being creative in a business mode. You have to be creative to make money. But don’t come and tell me you’re creative — this guy tried to sue someone whose game had “Saga” in the name. Come on, are you serious? All your games are similar to all your other games.

Just be honest about it. You’re here to make money? That’s fine. That’s not a problem. But don’t talk to me about being creative. You want to be creative in the industry at making money, that’s fine. But not creative — also they compared themselves to Pixar. Oh, yeah, sure. Okay, I’m not gonna talk shit.

Cage: Too late, Josef.

Fares: Yeah, too late.

Cage: So, what was I saying? At the same time, if you look at the charts last year, it’s mainly single-player games, whether it’s Red Dead or God of War or Spider-Man. There’s an appetite from players for different types of experiences. I’m glad they all exist.

GamesBeat: I think we’ve wound up the audience a little. Does anyone have any questions in the audience?

Fares: We have more jokes if you guys want.

Cage: We can work on a show, a two-man show.

Above: Jodie, voiced by Ellen Page, is the star character of Beyond: Two Souls

Question: If I make a game about decisions, a story-driven game, how should I surprise the player with a hidden option, a second option, or third option? Something they don’t expect when they expect a binary decision or an obvious choice.

Cage: I don’t know, honestly. But it’s a good question. I don’t think there’s a magic recipe for how to surprise the player. Josef worked on a twist in his game. I worked on a twist for Heavy Rain. I think the twist is something that’s powerful and challenging to make, if you want to be consistent. But that’s one way.

For me maybe the secret to offering choices is to make sure there’s not just a good choice and a bad choice. It’s not about being black and white. What’s interesting is the shades of gray between the two. It’s always a question where the answer is not obvious. That will make you ask yourself what you would do if it was happening to you. You have to think about it.

I often mention a gamer who played Heavy Rain, and he left his console on pause for days because he couldn’t make up his mind about what he should do. He had to think about it. That’s the kind of choice I love. But that’s one way to surprise people, to ask them interesting questions.

Question: Did you use data from your previous games, the way the players that made certain choices, in your later games? And do you think in the future we might see a collaboration between the two of you?

Fares: Absolutely! [laughs] Why not? It would be nice to have a couple of directors, like they’ve done in movies. That would be really interesting. We could put it together.

Cage: I have a lot of respect for what Josef is doing. He’s a very talented director, of course. It’s more about the project and the opportunity to do it. As far as your first question, about statistics, we got some statistics based on the trophy system for the PlayStation with Heavy Rain and Beyond. With Detroit we had a more advanced statistics system, what we call telemetry, where we get exact data from the choices made by players in the world. We know exactly who made this decision, failed here, died there, and so on. We know everything.

I tend not to use this, because again, if you want to be creative, it’s very hard to take a sheet of data and say, “I’ll write something like this again because it worked here.” I still believe I should be creative and have new ideas and find new challenges, rather than trying to use what I’ve done in the past somehow. I think each game is different. It has its own truth that you need to find. I don’t want to work with data. I want to work from creativity first.

Above: Brothers: A Tale of Two sons had a big twist in its story.

Fares: I like that approach as well. Approved. [laughter]

Question: We’ve seen a trend in video games around the theme of parenthood recently. We had God of War, The Last of Us. A generation of game developers have become parents. What do you think the next coming theme like that will be, as game developers get older?

Fares: I’m not a parent, so….

GamesBeat: Maybe being grandparents?

Fares: Maybe it’s about love stories. [laughs] It’s hard to know what the next thing will be. My hope is that we keep delivering unique titles and unique ways of telling stories, unique games in general. I do strongly believe that if you listen to your inner voice, even if it sounds very cliche, we’ll create some really cool, kick-ass games in the future. There’s so much to discover. I do hope publishers dare to take those risks and do more crazy ideas. Even if sometimes we fail, that’s not a problem. I hope that’s what the future holds, great games with unique ideas.

Cage: I think the key word for me is “relatable.” You create characters that you can relate to. For me that’s something new. In the past we created a lot of games where the characters, the main characters, were superheroes, big muscles, no fear, no weaknesses. And now we’re starting to have heroes who have their own needs and their own weaknesses. They’ve become much more relatable because of that.

When I worked on Heavy Rain, my idea was to create something that people could relate to. I thought, “I’m a father. I have a father. I understand this relationship.” This is why I felt truly engaged in the experience. That’s part of the success of God of War. It’s because they made this character much more relatable.

Above: Detroit: Become Human was an exploration of good AI and bad people.

Question: What do you think about the fashion or the way video games and cinema merging into one thing? Do you think we’ll see a fusion between those two mediums? Is that a good thing?

Fares: I wouldn’t necessarily agree on that. I think they’re two different mediums. If you look at books and music and theater, every medium has its way of telling a story. I do believe that — of course, having a background as a filmmaker, you have a lot of tools that have had time to be explored and tried. We’ve learned a lot over the hundred years that movies have existed. With games we have a lot to discover, and I believe that while we can get inspiration from movies, books, and other ways of telling stories, they’ll be their own medium. I don’t have any fear that either will take over, anything like that.

But I do believe that emotionally — if you have a story that’s super strong, super impactful, it could be even more impactful if you’re actually part of it. The interactivity adds another layer in a way that movies can’t do. But I don’t think that will take over. There will always be different media.

Cage: I agree. When photography appeared, it was about copying painting somehow. And then when cinema appeared it was copying photography. All media learn from each other. I think the essence of interactivity is very different. It’s about creating something with people. It totally changes the language. It’s fine that you borrow some parts of your language from films or poetry or art or whatever you want, but you need to make it something unique, because you need to create this language of interactivity that will allow you to create something with people. For me that’s the heart of it.

GamesBeat: I am a little worried about what happens when a combat game looks more like a documentary, and the theme switches to the blurring of the lines between soldiers and civilians, like in the latest Call of Duty. The content becomes very disturbing. The gameplay potentially puts the player in a place where they shouldn’t be. Video games are fun, for the purpose of fun….

Fares: With that I don’t necessarily agree. It’s not only about fun. It’s about interactivity. It could be fun, but — there are many scenes in video games that are great, but they’re not about fun. They’re about the scene itself, about feeling.

Cage: I agree with Josef. Games can be more than fun. There will always be games that are fun and that are played because they’re entertaining, but we’re starting to discover with this medium that we can do something else. We can use it to say meaningful things about us and about our world. Which is a danger, because with what you’re saying — now we can talk about things. We can say unpleasant things. We can say things in the wrong way. But what I want to remember is that now we can say something that’s relatable and connected to our world. That’s what I love about this evolution of games.

Question: Would you have advice for developers getting started, trying to get into a position to make more emotionally involving games?

Fares: For me, when I believe in something, I won’t stop. I’m ready to go all the way. I’m a nice guy — I’m not mean to anybody — but I never stop going after what I believe in. I have extreme self-confidence. I can’t help it. I know you’re not supposed to. I know you’re supposed to feel a bit insecure. But I just don’t. When I do something I just believe in it so much that nothing can stop me.

If I’m in a meeting, I know what’s going to happen before people even know what I’m going to say. I don’t know how to tell you this. It’s just something I feel. It’s how I ended up in this industry. When I decided to do it, it happened. I don’t have any formula — do this and you’ll be come successful. Maybe the reason is because I don’t have kids like David does. I can take more risks.

I know in A Way Out, my accountant said to me, “If you keep going like this you’re going to lose your house, lose everything.” Okay, yeah, whatever, I don’t care. I could literally be on the street begging rather than doing something else I don’t like. I need to feel that passion. If you gave me $100 million I’d say know if I didn’t feel it in here. I’m a passion-driven guy. I need to have that.

The only tip I could give is that being really true to yourself is one of the key points for trying to understand what your inner voice is, what you want to do, what you want to create. It’s something you feel in here. If you connect with this — that’s all I’m saying. Just feel it.

Above: Josef Fares repeats himself: If you don’t like A Way Out, you can break his legs — and arms.

Cage: It’s always a different mixture to find between listening and trusting yourself, and at the same time listening a little bit to others. If you only listen to others, you never do anything. At the same time, if you never listen to others, sometimes you do stupid things. It’s finding the right balance. But believing in yourself is the most important thing, because very few people will do it for you. Believe in what you want to do and who you want to be and fight for that.

Fares: I do listen to a lot of people. It doesn’t look like it, but I really do. I’m super flexible. If you ask my team, my attitude is, try everything. Let’s try to turn every stone over and figure it out.

Question: The general public, we know the names of directors in film much more than we know the names of directors and creators in games. Why do you think that’s the case?

Fares: It’s coming. In the game industry, everybody knows your name. Directors are becoming more and more — I think it’s important to have — coming from a movie background, very quickly, I would still argue that gaming is more of a collaboration. It’s as important in movies, though, that you need a voice or two that’s pushing the vision. That’s important. Of course it’s a collaboration, whether it’s a big team or a small team, but you need to have a voice there. Games, more and more, understand that.

We tend to see that games that are really interesting have one or two people pushing it. We see that in God of War, in your games, in the Naughty Dog games, in the games we do. In the future that will become bigger. And let me tell you this — a lot of movie directors are way overestimated. It’s way easier to direct a movie than anybody thinks. I can have a 10-year-old direct a movie. [laughs] I’m telling you! If you have a good DP….

GamesBeat: What do you think of the Oscars, by the way? [Audience laughs]

Above: Connor confronts a rogue android in Detroit: Become Human.

Fares: Fuck the Oscars! No, no, no. The thing is, what I’m trying to say is that movie people sometimes take themselves too seriously. Come here and make a game and we’ll see how cocky you are, motherfucker. I’m telling you! I made six movies and it’s a walk in the park compared to making a game. I’m not saying it’s easy, but it’s definitely easier. You have your DP there and you say “Action!” and then you go have dinner. I’m just saying people underestimate how hard games are to do. We deserve more respect. I don’t know why I get so excited about this.

Cage: What can I say after that? Well, I can’t say I agree with you, but — I mean, you know many game directors. Everybody knows probably, what 10 big game directors out there? There will be more and more. But it’s true that it’s collaborative work. There are many people involved. It’s been true that we’ve promoted teams and the names of studios much more than the people behind them.

It depends on the games. If you do a sports game, maybe the role of the game director isn’t the same compared to something that’s built around narrative. But I think it’s going to evolve in the near future.

During the Q&A session, a reporter asked Cage about allegations of harassment and other problems at his studio. Ivan Fernandez Lobo took the microphone and asked to move on to the next question. Lobo later explained that he wanted to create a safe space for his speakers to talk, and he also said the reporter was free to ask that same question privately.

Disclosure: The organizers of Gamelab paid my way to Barcelona. Our coverage remains objective.