Summer used to be a slow time for games. After the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3), the big game industry show in Los Angeles, everybody took off on vacations and then hunkered down to ship games for the fall. But this isn’t the model anymore. The news keeps coming on all fronts, such as from virtual reality technologies to the Gamelab event in Barcelona, Spain or esports news such as the Overwatch League announcement this week, as well as our own MobileBeat 2017 conference.

This gives me more reasons to interview smart people in the game industry and collect a lot of quotes from executives, CEOs, investors, and game creators about their views. This week’s column takes snippets of wisdom that I’ve gleaned from those interviews.

I’ve shared those quotes in this column below, and hopefully they don’t seem random. It’s fun to see trash-talking alongside visions of the future.

Also, here are quotes from the leaders we interviewed at E3 2015 and E3 2014. And here’s part one of my post on smart musings from game executives from last week. A few of the first people quoted here — Clinton Foy, Kevin Chou, and Noah Whinston — will talk about esports at our upcoming GamesBeat 2017 conference in San Francisco on October 5-6.

Clinton Foy, managing director at Crosscut Ventures and chairman of the Immortals esports team, and Noah Whinston, CEO of the Immortals, were two of the winning bidders (estimated) $20 million) for a franchise for the Overwatch League for the Los Angeles market.

“I’m super-fascinated by esports. It’s community led. There is a strong community around Overwatch now, and we want to build it. There are not many chances in your lifetime to be part of something that is big as this. It’s starting a new sport. That got me excited,” Foy said.

On competing with other Overwatch League owners like Robert Kraft, owner of the New England Patriots, Whinston said, “Oh, we’re relishing the opportunity to kick some ass on Robert Kraft.” [Laughs].

Above: KSV eSports International founders Kevin Chou (left) and Kent Wakeford. They previously ran Kabam together.

Kevin Chou and Kent Wakeford, the former top executives of mobile game company Kabam, also bought one of the Overwatch League franchises in Seoul.

Wakeford said: “At Kabam, we were always thinking about the esports market, and the excitement around it continued to resonate with us. Newzoo estimates it will grow to $1.5 billion by 2020, and my view is that is a very low estimate.”

And Chou said, about attending his first esports event a few years ago: “It was unbelievable to be a part of that. It dawned on me. If this takes off like live music concerts or live sports events, it would become huge. … I like being the underdog,” he said. “I felt we were that for a very long time. The traditional sports teams have their venues, their front and back offices. But I bring a different view of this as an avid fan of these games. We have as good as a shot as anybody. We have a lot of resources at our disposal.”

Adam Fletcher, CEO of game analytics and AI firm Gyroscope, said in a panel on artificial intelligence at our MobileBeat 2017 event: “It’s critical to understand your users, no matter what. That’s critical from the standpoint of narrative development all the way to understanding the lifetime value of your user base. Personalization, what A.I. brings, what I want it to bring at least—as someone who plays a lot of games, I want to have fun. I’m here to play games and enjoy myself. I recognize there’s a balance between creative needs and business needs, and I think A.I. can successfully balance those two things.”

Above: Rami Ismail of Vlambeer condemns harassment that shut down a women’s gaming meetup in Barcelona.

Silicon Valley had its world rocked as the New York Times wrote about sexual harassment of women by powerful venture capitalists. But it is far from the only place where women are having trouble. Rami Ismail, cofounder of Vlambeer, excoriated Spanish rogues who threatened to shut down the first-ever women’s meetup for game developers in Barcelona, Spain. They said they would infiltrate the event by dressing up as women, forcing the venue owner to shut down the event.

“Special interest groups exist in the industry,” he said. “We can learn from having focused and open discussions about shared issues. Groups like this exist for C++ programmers or people who do orchestral music. They can talk about issues in a safe space without the worry of harassment. That’s no different from an event like this for women. I don’t care if you agree or disagree with them. What is important is that you show your support for events like these, to show people who are in the industry, those who passionate about games, that our industry is welcoming and it is safe. The actions of these harassers is damaging. Game development is affected by this. This is damaging. This news goes around the world. How professional is this industry if people can’t even meet up without being worried about their safely? That’s not the fault of the organizers. That’s the fault of the harassers.”

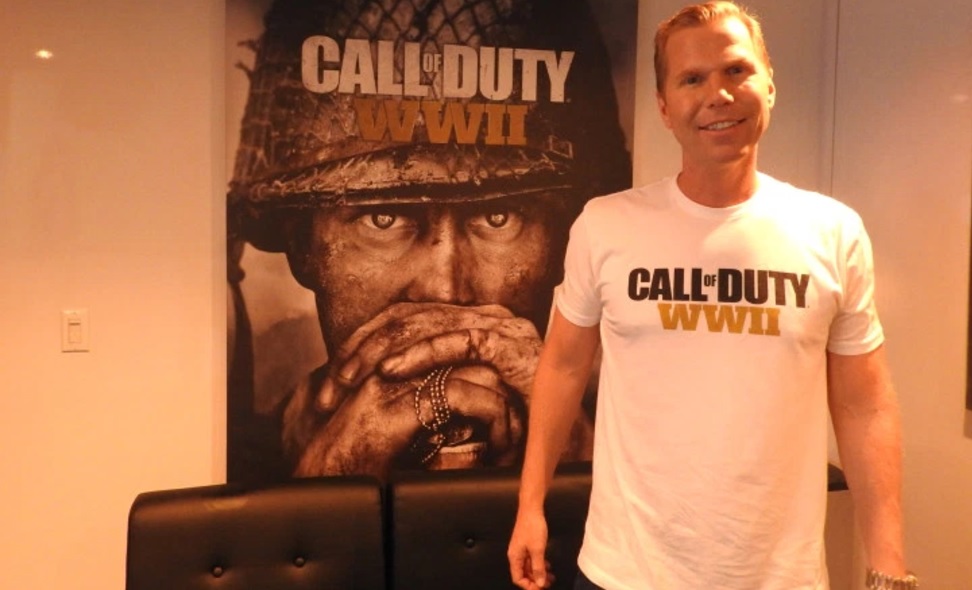

Above: Michael Condrey, co-CEO of Sledgehammer Games, maker of Call of Duty: WWII.

Michael Condrey, cofounder of Sledgehammer Games, had a chance to show off Call of Duty: WWII at E3 2017. He talked about the responsibility that game developers have to be true to the experience they’re depicting.

“One of the great opportunities we had on this game creatively is that the cause is so well-known,” he said. “It’s an iconic war of good versus evil. We didn’t have to spend so much time creating a universe and getting you to believe in the protagonists and antagonists. It becomes a more personal story. It honors what really happened – a world on the edge of tyranny and chaos. That’s been rewarding. As we talk to veterans and work with our military historian and travel around to these different battle sites–the weight of being respectful has come through, I hope, in the campaign.”

Above: Vander Caballero of Minority Media at Gamelab.

Vander Caballero, CEO of Minority Media, maker of VR games like Time Machine, spoke with me at Gamelab about how long it will take for the virtual reality games market to take off.

I think it’ll start in three years, but it might take another seven to catch up. The tech might be there, but it’s a matter of people getting used to it. My background is in industrial design, so what I learned in school is how you introduce new technology or new objects into people’s homes. It’s not easy to change behavior and expectations. It takes years. We’re getting better and faster at doing that, but the change VR represents is huge. … It’s pretty close. It’s just a question of how we survive the desert.”

Above: Massimo Guarini, creative director at Studio Ovosonico, maker of Last Day of June.

Massimo Guarino, CEO of Ovosonico, an Italian game studio that is working on Last Day of June for 505 games. It’s about a terrible accident that occurs — and what the player can do to prevent it from happening after replaying the story over and over. He spoke at Gamelab about why video games aren’t reaching larger audiences.

“You cannot just dismiss music as a whole. You cannot say I hate music. The same goes with movies. Maybe you hate horror movies,” he said. “But it happened to me quite a lot to hear people say I hate video games. It’s very common to accept the notion that an entire art form — because I consider video games an art form — can be dismissed like this. I found it to be really weird. This is just as games are starting to speak different languages and show some diversity. It’s an emotional response. In a broader audience, not everyone is interested in overcoming challenges. As an industry, I believe we are not communicating in the right way. Maybe we need to make the games easier. I don’t think that is the right solution. That’s like making a book’s font bigger, without changing the content. I feel we have a problem. The first step for us as game developers is acknowledging we may have a problem, acknowledging it is difficult in 2017 to make a game that deals with different subjects and expect this game to have the same commercial results as a game where you shoot at zombies.”

Above: Richard Bartle, professor at the University of Essex.

Richard Bartle, professor of computer game design at the University of Essex, talked about why some folks quit playing some games, including complicated experiences that have lots of content and a long story.

“‘Complicated’ can just have to do with how hard or easy it is. For you that game could be too shallow. You want something meatier. You think, ‘I know this game. I’ve played this game before under different names.’ A Japanese role-playing game might have 120 hours of content, but it’s all going from A to B to C, and if I’m interested in the story I can just look it up on Wikipedia. Why am I grinding here? It’s really hard to kill all of these monsters. I have to kill a thousand furballs, but what’s being said here? When you think about what’s being said, it’s either, ‘We don’t have any content so we’re making you grind,’ or it’s, ‘We’ve given you the grind in order to make what happens afterward feel better, feel like more of an achievement, feel like it’s worth something.’ It’s not until you get through the grind that you figure out which one it was.”

Above: Mikko Kodisoja, cofounder of Supercell, at Gamelab in Barcelona.

Mikko Kodisoja, cofounder of Supercell, spoke with me at Gamelab about the kind of companies the maker of Clash of Clans is investing in, the kind of games it wants its partners to make, and the need to be really harsh in making high-quality games.

“When we talk with the guys we’re going to invest in, we talk about their vision and what kind of games they want to make,” he said. “That vision has to align with ours. We want to make games that last for decades, even. People play them and remember them. All the studios we’ve invested in have that same kind of mentality. To accomplish that, you have to be really harsh at times. If the game is not going to succeed — if the retention metrics are lower than expected, for example — then you know that it’s not going to be this kind of multi-year hit. Then you just have to do something to — usually you kill the game, to focus better. That’s something we trust teams to do if they don’t see success. We try to help them wherever we can, but at the same time we have to concentrate on our own stuff.”

Disclosure: The organizers of Gamelab paid my way to Barcelona. Our coverage remains objective.