My Cuphead social storm lasted about eight days. During that time, gamers near and far criticized me for playing a demo of the upcoming video game Cuphead so poorly. I’m still absorbing the lessons of this hate-filled episode, where complete strangers by the thousands insulted me because I wasn’t qualified, in their eyes, to review video games. I can’t see what lies beyond the Cuphead video about “my 26 minutes of shame.”

But a few lessons have crystalized for me.

I realized that playing games is therapeutic. While I was in the storm, I finished playing Knack 2 on the PlayStation 4. One line in Sony’s game resonated with me: “We all make mistakes. What matters is what you do next.” It felt good to play a game and demonstrate just enough skill to get through it, even as people were accusing me of the “game crime” of having no skills. Having failed at one game, I played another.

As I noted last week, I’m grateful so many friends and strangers came to my defense or lifted my spirits. They showed me kindness in a dark time. I’ll remember that. Maybe the news about hurricanes deflated my social media mess. But I’d like to think that the people who stood up for me and vouched for my dedication to games mitigated the hatred. Thank you for that, as it’s a personally risky thing to defend someone from a mob.

Some friends confessed that they weren’t all that skillful at playing games, but were afraid to say that publicly. Many longtime game developers revealed they were bad at playing their own games. As I expressed in the middle of the storm, these people shouldn’t have to hide their lack of skill. Not everyone is an esports athlete, and the bulk of us are bad. We can wear that as a badge of honor, as it helps us bond with each other. We play games because they are fun, not just to beat each other up.

On top of that, many said they sympathized with my lack of time to play games. We all have growing piles of shame because we have millions of games available to us across PCs, consoles, virtual reality, and mobile devices. Our gaming culture has fragmented in many directions. We once had a shared heritage around games like Pong and Mario. But how many of us know Limbo or Bastion? As this fragmentation happens, I don’t think we need to devolve into different tribes, putting down those who play social games or mobile games.

I try to play every kind of game across all platforms, and I realize just how Herculean a task that is. Even if I played 100 of the best games a year across all platforms, I’d have to finish a game every three days. Having put 80 hours into Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor or 400 hours into Total War: Attila, I realize that I can dabble in many games, but I have to focus my valuable hours on the ones I really love. And as I put more hours into the games that I love, I realize that I’m not good at whole categories of games, like platformers. Should I feel guilty about that? Should we all?

I use my free time to play mobile games like Clash Royale, Dawn of Titans, and Pokémon Go. I play first-person shooters on the consoles like Call of Duty, Halo, and Battlefield. I enjoy strategy games like Total War on the PC. I play Nintendo games on the couch with my kids when they have time. I like the occasional virtual reality experience or a visit to the arcades. And I enjoy original and innovative games on just about any platform. But it’s a hopeless cause to try to play everything because I can’t entertain myself all of the time. I don’t know anyone who is a walking game encyclopedia.

This shame thing is a big problem for the $108 billion game industry. If gaming is to get bigger and become the dominant form of entertainment, it has to make people feel more welcome and less intimidated. I don’t think it’s a shame that we have piles of unplayed games. I think it’s a shame that people are mean about this and use it to put down others.

Some of my acquaintances told me they essentially “retired” from gaming because they wanted to leave the culture of one-upmanship behind. A lot of haters told me to quit gaming. But I’m not willing to surrender my favorite pastime and leave it in the hands of those who want to drive everyone else out. Games have the potential to bring us all together in peace.

The “us versus them” reaction that I felt was pressure to “git gud,” or play games with skill or back off on talking about them. I understand basic truths like you shouldn’t review a game you haven’t finished. But we don’t have to exclude people from the community of gamers because they simply try out a lot of games and never finish them. Our one shared experience is that we all want to play games, and none of us has time to play them all.

I’ve learned that it pays to put more time into playing. But the warmest response I received from last week’s DeanBeat was my plea to consider unskillful gaming as authentic as skillful gaming. It’s OK not to finish games, and it’s not your fault if you don’t have the time to play.

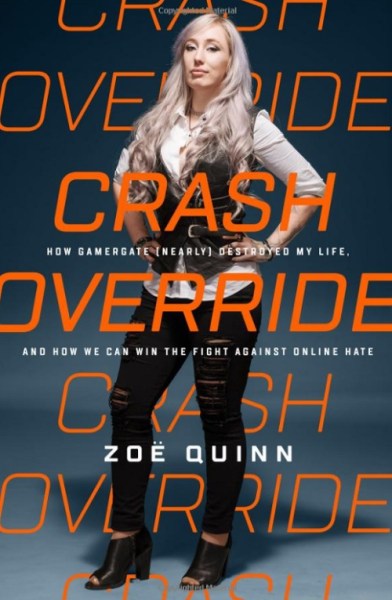

Above: Crash Override

I’m just starting to read Crash Override, Zoe Quinn’s new book about getting harassed in the Gamergate controversy. I have a newfound empathy for people who endure social media attacks, and I talked to some of them. The attackers take great offense at someone else’s transgressions, whether imagined or not. They vent, get tired when they receive no response, and then go away. In Quinn’s case, that didn’t happen, as Gamergaters turned her life into a living hell for two years. She turned it into something positive by creating an organization, Crash Override, that helps people deal with online abuse.

The small similarity between Quinn’s case and my own was misinformation. Gamergaters were outraged that she, as a game developer, might be trading sex for positive game reviews. Those railing about ethics in game journalism conveniently didn’t notice that the reviewer in question never actually reviewed her games. In my case, a fellow game writer clipped out the worst segment of my gameplay, which wasn’t even a game review but part of a video from a preview event, and shared it around.

He and his followers criticized me for being unskillful at one game, and therefore all game journalists were unqualified to do reviews. They didn’t acknowledge that, for the most part, I write about the business and technology of games and only occasionally do game reviews. Many people who were angry at me didn’t know that I was not a full-time game reviewer. When they found this out, they softened.

Reading a book like Quinn’s could be therapeutic for me, as I realize I am not alone. Friends who have been through online hatred told me not to engage with hostile people. I tried to deal with the most hateful people with kindness. I expressed my views, shared more than I should have, and came under attack anew when people twisted my words for their own benefit. I got sucked into some arguments. One acquaintance said, “Dude, you gotta stop responding, not healthy.” Eventually, as I stopped engaging with them and started retweeting my latest, non-controversial stories, the harassment trailed off to a trickle.

Above: Games at a Japanese publisher. No way can I play them all.

If you respond in a shitstorm, I think it helps to be kind and human. I offered kind words to strangers who were being mean. A handful of them responded with their own kindness. I think it threw them off-guard. They expected me to relentlessly defend myself. Sometimes I did. That usually accomplished nothing, particularly on Twitter. I offered to get on the phone with a couple of them. One plans to take me up on that offer, but a few of them turned tail and ran when I made that offer. I think that setting up some kind of conversation or dialog with people who disagree with me is a good thing. It’s a basic tenet of journalism to get a diversity of views. I’m aware of the false equivalencies that abound in our society, but I try to be receptive to another’s point of view. I’m willing to do have that conversation, when it’s safe.

I learned something new about the Gamergate advocates as well. They feel disenfranchised, for sure. But they also want to be acknowledged as individuals. They hate the notion — which both Quinn and I repeated — that Gamergate’s hate led to the rise of the alt-right and the election of Donald Trump. I believe this is true for some of these people, as you look at a publication like Breitbart and its role in all three of those developments.

But the Gamergaters said they were a diverse group and that not all of them were Trump supporters or alt-right advocates. They said that not all of them were into harassing people with extremely harsh language. These people piled on me but in a thoughtful way, not a mean way. Some of them simply wanted me to be more transparent and authentic, acknowledge that I was worse than I thought, and try not to dodge or deflect.

I’ll grant them that. And all Gamergaters are not exactly the same. They’re all individuals. They’re all human beings. I should treat them as human beings, and they should treat me like one, too. During the last couple of weeks, we didn’t see each other as human at all. To me, they were a faceless mob. To them, I was a symbol of bad game journalism. I hope to break through this. I’m willing to turn around and treat them with kindness, and maybe we’ll have a chance to play games together someday.