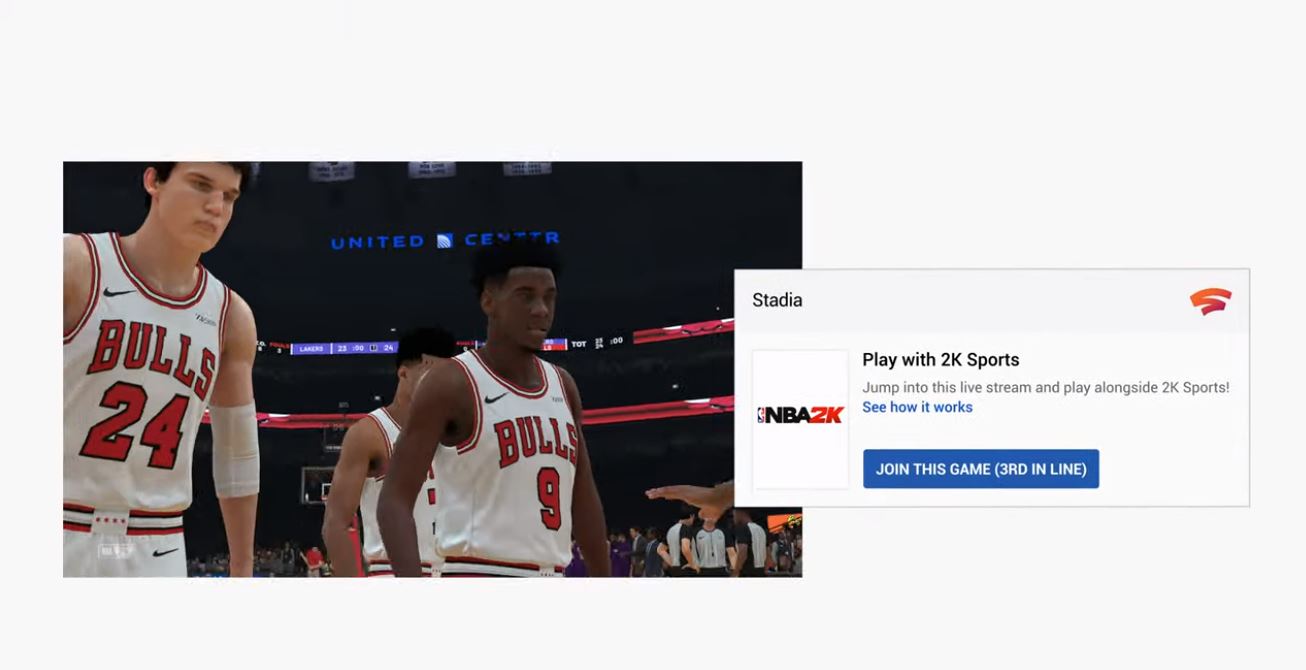

Above: Crowd Play through YouTube and Stadia.

GamesBeat: Did you ever have any temptation to do a console because that was what people expected of you?

Harrison: None whatsoever.

GamesBeat: That defeats the purpose of it.

Harrison: Correct. Not only does it defeat the purpose, it would hold back our vision of the data center being your platform. It sounds like a buzzword, but it’s very intentional that we describe ourselves as a new generation for the 21st century.

We have got to this inflection point in the industry where — let’s say, for argument’s sake, the industry is 40 years old. For the last 40 years, games have all been device-centric, meaning as a developer I build for the capability of the box. They’ve been package-centric, meaning a floppy disc, a cartridge, a cassette in some cases, an optical disc, or more recently a downloadable package. But still, those two philosophies have constrained the development process and the design thinking of games.

Now games are network-centric, completely network-centric and device-independent. The industry won’t transition from one state to another overnight, but we hope that Stadia becomes the tipping point, the fulcrum that helps that transition begin.

GamesBeat: The things that seem fairly brilliant — this controller, with the faster speed, and the YouTube integration — it looks like you can do that without hardly any bandwidth costs. You already have that stream in the data center. You know what the player is doing. All you really need to know is what the player said, or a little video of the player saying it, going back up from the user’s home to the cloud.

Harrison: Actually, it’s even more impressive than what you just described. Our technology is so capable that we actually have two simultaneous 4K streams coming out of our platform. Let me qualify that. One which is up to 4K, depending on the bandwidth you have into your home. If you have slightly lower bandwidth, we’ll bring that resolution down to 1080p. But there is always a second stream available which you can send to YouTube, which is always 4K, 60 frames per second, HDR.

Above: Jade Raymond at Stadia launch.

GamesBeat: I get 200 megabits a second downstream, but only five going back up. It sounds like that would be a challenge to deal with. Whatever you’re sending back up, is it not that much?

Harrison: It’s just joystick commands. It’s tiny. It’s bits.

GamesBeat: I guess what I’m not understanding is voice. If you’re talking on a stream, the voice originates in the home and has to go up.

Harrison: But still, it’s compressed. It’s a few hundred kilobytes. We’ve put in some redundant data to do error correction and stuff like that.

GamesBeat: I may have the wrong impression, but when you’re playing something like Apex Legends and all of a sudden everyone stops talking, you wonder if the game was able to handle that.

Harrison: The contention issue you describe in a multiplayer game is probably not a function of your upload speed. It would be a function of the way that voice is matched and multiplexed at the server level.

GamesBeat: But the point is, you don’t have to send up a ton of stuff.

Harrison: Yes, it’s tiny. It’s kilobits per second, not even megabits per second.

GamesBeat: The split-screen feature was also unexpected. I didn’t realize that this was the reason it disappeared from games, that they’re so networked now that they can’t afford to be sending this stuff.

Harrison: It’s also because of the complexity of the visuals. For a game, within its engine, to divide the resources in half and give you two separate views of the world — particularly games that are using internal streaming, meaning streaming from a disc or from memory — it’s really hard to do. It’s almost the first design feature to get cut. But now, with Stadia, that comes back, and not just two, but four or eight. We can internally stream from game to game. We showed that in the demo yesterday. Developers are very excited about that.

Above: Phil Harrison shows the Stadia controller.

GamesBeat: Google likes to think long term. I’ve heard some long term concerns that people have. One was, if we’re going to have a trillion things connected on the internet, according to Masayoshi Son — there’s a lot of AI there. But there’s so much data that a lot of the processing in the future is expected to go to the edge, and not to centralize in the data centers. And they’re saying that’s because there’s too much data to send. You have to look at the data, process it, and figure out what you want at the edge. That’s a whole shift of computing from an assumption of data centers centralizing it to everything computing in all locations. You might have a lot of traffic on the internet in the future that you have to contend with, as both Google and Google the game company. Is that something to worry about?

Harrison: No, it’s not something to worry about. I agree with the trend, that there is going to be more data and more demands on our infrastructure, but that’s exactly why we have made those fundamental investments in our own backbone that connects all of our data centers together. We’re not touching the public internet. I agree with you, but it’s not something to be concerned about. That’s one of the long term investments that Google continues to make.

GamesBeat: The other thing that’s come up is that data centers are going to melt the polar ice caps if you’re successful.

Harrison: Well, actually, that’s a very easy question to answer. All of Google’s data centers run on green energy today. There’s a great blog post on Google which will give you details about how we do that.

GamesBeat: As far as how much content and how many games you have to make, what have you thought about that?

Harrison: I don’t know that it’s the volume of games. We’ve had conversations over the years many times about what it means to be a first party. A first party studio is the studio that can help bring the platform to life in a unique and exclusive way that helps raise the bar for everybody. What Jay talked about quite right was not only are we going to do that, but to every extent possible we will share those learnings back with all developers on our platform, so that everybody benefits.

That got a cheer, quite rightly, because I think that is a philosophical shift that the industry needed. We want to make sure our studio, internally and externally, create those beacon, lighthouse experiences that demonstrate–”Oh, that’s what it means when the data center is your platform. That’s what it means when ML and AI become part of games. That’s what it means when conversational understanding and natural language processing from the Stadia controller to the game allow you to chat with an NPC in a believable way.” There are things we can push on that are going to help the industry.

GamesBeat: You see those as things that will make your games different. There was that mention of thousands of people in a battle royale game, instead of just 100.

Harrison: Yes. Now, whether it’s fun to have a 1,000-player battle royale was not the point. It’s more about the technical capability of it.

GamesBeat: How do you succeed in getting good people like that to work on this?

Harrison: I’ve been really happy with the team I’ve been building. More than half of my leadership team now comes from the game industry. We have some very seasoned talent. We have some great new passionate thinkers. It’s fun seeing the inside of Google that Sundar alluded to yesterday. There are a lot of passionate gamers who got into tech because of games. They work at Google. They’re now able to bring their talents to a game platform. It’s a win-win. It’s not just about hiring people from outside of Google. It’s also about finding those talents from inside.

Above: The Stadia controller from Google.

GamesBeat: As a game executive, do you feel like you need a certain amount of autonomy from the top? Sony managed, over many years, to have games as an island of executives, it seems, free from the interests of the other parts of the company. I heard someone at Amazon asked if they would set up their game business that way, and the response was, “No, we would not. We would operate as one company.” That person turned down the job, because they believed that in some ways, the game executives needed autonomy.

Harrison: Google has, rightly or wrongly, trusted me with a huge amount of autonomy to build this vision and tell this story. But I can’t do this on my own. What I love about Google is the collaborative nature of the company and the fact that I have partnerships all across the company, from YouTube to our technical infrastructure to Google Cloud to our hardware business, who are participating and partnering with us to make Stadia real. It’s not just my team. It’s a much broader team.

You saw, with Sundar as part of our presentation yesterday, that we have the support and investment from the top. But we do have the autonomy when we need it.