testsetset

Google is finally taking the game business seriously. Not satisfied with its role as owner of Android and the operator of the Google Play store, the company announced Stadia at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco on Wednesday. It was one of the most ambitious announcements of the last decade — a full declaration that Google cares about games. And it was the talk of the show.

Stadia is a cloud gaming platform that resides in Google’s data centers, which compute the graphics and actions in a game and then send the results in the form of a video to the player, regardless of which machine the player is on. It lets gamers play high-end games on low-end machines, including TVs, smartphones, tablets, PCs, and lightweight laptops. It will be able to run single-player games like Doom Eternal at 60 frames per second in 4K resolution with HDR (or high-dynamic range).

It comes with a controller that has a button that lets you capture your gameplay and share it directly to YouTube. Fans who watch the YouTube video can click on a link and immediately go into a game to try it out, or even join a streamer in a match. The controller will connect to WiFi networking that will lead you to Google’s backbone network that will minimize interaction delays, or latency. Stadia will also be able to play games in a split-screen mode.

To lead the business, Google turned to an industry operator who has a lot of cred. Phil Harrison ran Sony’s worldwide game studios and served as an executive at Microsoft’s Xbox game business. And this week, he made his first public appearance onstage as a vice president and general manager in charge of Google’s Stadia business. I’ve known Harrison for years, and I was able to sit down with him and quiz him about the big questions of the Stadia business.

Here’s an edited transcript of our interview.

Above: Stadia is the plural of stadium, in case you were wondering.

GamesBeat: I get the feeling that Google and Stadia have been the talk of the show.

Phil Harrison: That’s kind of intentional. [laughs] But it’s nice to know it was all worthwhile.

GamesBeat: What convinced you to sign up with Google in the first place?

Harrison: I wouldn’t say I was done, but I was as far away from corporate life as you could possibly imagine. I got a call — long story short, I said, “No, I’m not looking for a position, but let me see if I can be helpful to you in maybe finding the right person.” But I was convinced to take a phone call, which turned into a video call, and I said, “Oh, that’s kind of interesting.”

I met with Sundar and Rick and Ruth, and I started to understand not just the vision that Google had, but also the constellation of capabilities that Google had. If we could line up the planets properly, it would be, no pun intended, a game-changer. I decided that I was so excited by that that I would move from the U.K. to the U.S. and bring my family. You can get a sense of my commitment.

GamesBeat: Somewhere there they convinced you that the cloud for games was going to work.

Harrison: My analysis was that cloud streaming, the math and the science of cloud streaming, was proven. It was more the scale of infrastructure required. It’s all very well doing it in a test or a trial or a regional basis, but to get to the kind of scale takes a Google. I think you run out of companies before you run out of fingers on one hand, that can do this on a global scale.

Nobody else has YouTube. Nobody else has the investment in the fundamental hardware architecture fabric inside the data center, which we don’t actually talk about publicly as to what is. But the level of innovation and hardware that Google has been investing in for 20 years is extraordinary. Coupled with — Google likes hard problems. We like to go for the difficult things that will transform an industry and take it to a completely different level.

GamesBeat: Very quickly, what are all the questions you’re not answering right now? Nothing about business model, nothing about subscriptions, nothing about launch dates. What else?

Harrison: We did have a launch date. We’re launching 2019.

GamesBeat: That’s a bit of a vague one.

Harrison: I’ll give you more specificity. It’s going to be closer to the end of 2019 than the middle of 2019. [laughs]

Above: Google’s Stadia game controller.

GamesBeat: One thing I heard when talking to people was, “Oh, there’s a gotcha here. They never mentioned the actual latency.” But I thought that if you could play Doom Eternal to the satisfaction of people like id, you must have solved that.

Harrison: We believe we have solved it. While we objectively have solved it with Doom Eternal, and we’ll encourage you to form your own opinions, we also would point you to a very technically astute, deep editorial on Digital Foundry. I don’t know if you’re familiar with Digital Foundry. They had a chance to look deeply into our latency, and they said that it was — I’m summarizing, but basically the same as an Xbox One X locally. Completely independently.

We will continue to make investments on our codecs, on the hardware inside our data centers, and on the intelligent networking traffic that we’ll build on top of that. We’re not done. We’ll continue to innovate on that. Then the final piece of the puzzle is the proximity of our data centers to the general population. The 7,500 edge node locations around the world we talked about yesterday, that’s a very significant capital investment, which allows us to get close and cheat the speed of light as much as we can.

GamesBeat: The controller had a clever thing in it that shaves some milliseconds off?

Harrison: Yeah, quite a significant amount of time. It’s WiFi directly to the data center in the cloud. It does not pair at all locally with your device.

GamesBeat: How is it making that hop?

Harrison: It’s effectively a computer inside it that talks directly to your WiFi network, and then connects directly to the game instance in the cloud.

GamesBeat: Is it okay to have this be wireless, then, and to have it communicate?

Harrison: It’s absolutely wireless, yeah. We showed it connecting to the TV yesterday for purely presentation reasons. You invite 1,500 people into a room full of WiFi, you can cause some unintentional consequences. That’s why we started with it being wired. But it’s a wireless controller.

GamesBeat: I’ve been talking to more people about data centers recently. I talked to Equinix, and they said they can get 60 milliseconds anywhere in the country [and with four corners of the U.S. covered, that comes down to 15 milliseconds]. The crucial thing for them is to have the handoffs between different parties, like AT&T to Comcast or whatever it is. I’ve heard other people also talk about that, saying you can get delays in the last mile of some kind. How do you help solve that part?

Harrison: It’s two parts to that equation. One is what I call the pairing relationships that you have with the ISPs, and the other is the distribution of your physical infrastructure. Crucially for Google is the fact that all of our data centers are then connected together by our own proprietary backend, hundreds of thousands of miles of fiber-optic cable.

Above: Google was all over GDC 2019.

GamesBeat: Less handing off or no handing off.

Harrison: Almost no handing off in many cases. That means that across the country, New York to San Francisco, for us, is 20 milliseconds.

GamesBeat: Valve said their network needs to do 30 to 60 milliseconds in response time in order to run Counter-Strike: Global Offensive and DOTA 2. That’s the way they do it, not as a cloud game. But if you have that, then players are happy.

Harrison: Sure, that makes sense.

GamesBeat: Does it mean you guys have to operate in that sort of realm, under 60 milliseconds?

Harrison: Some games are very latency-dependent. That’s why we showcased Doom Eternal. Talk to Martin and the team at id and they will tell you what their experience was like. They were satisfied, and they were rightly a tough customer, a tough partner to bring to our platform, because they were skeptical, as Marty said on stage yesterday. They didn’t think it would be possible, but when they understand exactly how it works, they said, “Okay, we’re all in.”

Other games are much more latency-insensitive. By demonstrating an action FPS with a very high framerate requirement, then all the other games that you can imagine go from there.

GamesBeat: As far as convincing the triple-A game companies, what part of that is difficult? How are you accomplishing that?

Harrison: I’m not going to answer the question in the way that you would hope, but you’ll see in the summer what our launch lineup and beyond looks like. We should have that conversation again. I think you’ll be impressed with the partners that we have brought to the table, brought to the party so to speak.

I would point you to what we did with Project Stream back in October of last year. We landed, day and date, with Ubisoft, the latest version of their most successful franchise. That should give you a sense of the direction of travel that we have for the kind of partners and the kind of games that we’ll be bringing to Stadia.

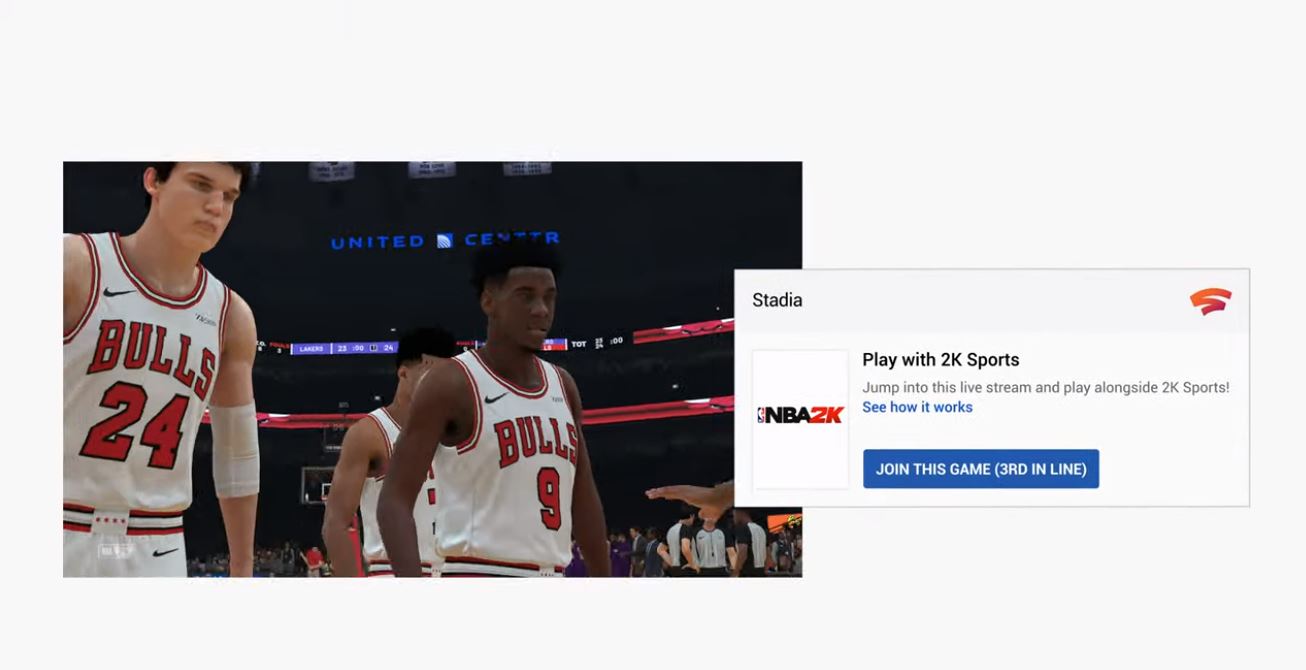

Above: Crowd Play through YouTube and Stadia.

GamesBeat: Did you ever have any temptation to do a console because that was what people expected of you?

Harrison: None whatsoever.

GamesBeat: That defeats the purpose of it.

Harrison: Correct. Not only does it defeat the purpose, it would hold back our vision of the data center being your platform. It sounds like a buzzword, but it’s very intentional that we describe ourselves as a new generation for the 21st century.

We have got to this inflection point in the industry where — let’s say, for argument’s sake, the industry is 40 years old. For the last 40 years, games have all been device-centric, meaning as a developer I build for the capability of the box. They’ve been package-centric, meaning a floppy disc, a cartridge, a cassette in some cases, an optical disc, or more recently a downloadable package. But still, those two philosophies have constrained the development process and the design thinking of games.

Now games are network-centric, completely network-centric and device-independent. The industry won’t transition from one state to another overnight, but we hope that Stadia becomes the tipping point, the fulcrum that helps that transition begin.

GamesBeat: The things that seem fairly brilliant — this controller, with the faster speed, and the YouTube integration — it looks like you can do that without hardly any bandwidth costs. You already have that stream in the data center. You know what the player is doing. All you really need to know is what the player said, or a little video of the player saying it, going back up from the user’s home to the cloud.

Harrison: Actually, it’s even more impressive than what you just described. Our technology is so capable that we actually have two simultaneous 4K streams coming out of our platform. Let me qualify that. One which is up to 4K, depending on the bandwidth you have into your home. If you have slightly lower bandwidth, we’ll bring that resolution down to 1080p. But there is always a second stream available which you can send to YouTube, which is always 4K, 60 frames per second, HDR.

Above: Jade Raymond at Stadia launch.

GamesBeat: I get 200 megabits a second downstream, but only five going back up. It sounds like that would be a challenge to deal with. Whatever you’re sending back up, is it not that much?

Harrison: It’s just joystick commands. It’s tiny. It’s bits.

GamesBeat: I guess what I’m not understanding is voice. If you’re talking on a stream, the voice originates in the home and has to go up.

Harrison: But still, it’s compressed. It’s a few hundred kilobytes. We’ve put in some redundant data to do error correction and stuff like that.

GamesBeat: I may have the wrong impression, but when you’re playing something like Apex Legends and all of a sudden everyone stops talking, you wonder if the game was able to handle that.

Harrison: The contention issue you describe in a multiplayer game is probably not a function of your upload speed. It would be a function of the way that voice is matched and multiplexed at the server level.

GamesBeat: But the point is, you don’t have to send up a ton of stuff.

Harrison: Yes, it’s tiny. It’s kilobits per second, not even megabits per second.

GamesBeat: The split-screen feature was also unexpected. I didn’t realize that this was the reason it disappeared from games, that they’re so networked now that they can’t afford to be sending this stuff.

Harrison: It’s also because of the complexity of the visuals. For a game, within its engine, to divide the resources in half and give you two separate views of the world — particularly games that are using internal streaming, meaning streaming from a disc or from memory — it’s really hard to do. It’s almost the first design feature to get cut. But now, with Stadia, that comes back, and not just two, but four or eight. We can internally stream from game to game. We showed that in the demo yesterday. Developers are very excited about that.

Above: Phil Harrison shows the Stadia controller.

GamesBeat: Google likes to think long term. I’ve heard some long term concerns that people have. One was, if we’re going to have a trillion things connected on the internet, according to Masayoshi Son — there’s a lot of AI there. But there’s so much data that a lot of the processing in the future is expected to go to the edge, and not to centralize in the data centers. And they’re saying that’s because there’s too much data to send. You have to look at the data, process it, and figure out what you want at the edge. That’s a whole shift of computing from an assumption of data centers centralizing it to everything computing in all locations. You might have a lot of traffic on the internet in the future that you have to contend with, as both Google and Google the game company. Is that something to worry about?

Harrison: No, it’s not something to worry about. I agree with the trend, that there is going to be more data and more demands on our infrastructure, but that’s exactly why we have made those fundamental investments in our own backbone that connects all of our data centers together. We’re not touching the public internet. I agree with you, but it’s not something to be concerned about. That’s one of the long term investments that Google continues to make.

GamesBeat: The other thing that’s come up is that data centers are going to melt the polar ice caps if you’re successful.

Harrison: Well, actually, that’s a very easy question to answer. All of Google’s data centers run on green energy today. There’s a great blog post on Google which will give you details about how we do that.

GamesBeat: As far as how much content and how many games you have to make, what have you thought about that?

Harrison: I don’t know that it’s the volume of games. We’ve had conversations over the years many times about what it means to be a first party. A first party studio is the studio that can help bring the platform to life in a unique and exclusive way that helps raise the bar for everybody. What Jay talked about quite right was not only are we going to do that, but to every extent possible we will share those learnings back with all developers on our platform, so that everybody benefits.

That got a cheer, quite rightly, because I think that is a philosophical shift that the industry needed. We want to make sure our studio, internally and externally, create those beacon, lighthouse experiences that demonstrate–”Oh, that’s what it means when the data center is your platform. That’s what it means when ML and AI become part of games. That’s what it means when conversational understanding and natural language processing from the Stadia controller to the game allow you to chat with an NPC in a believable way.” There are things we can push on that are going to help the industry.

GamesBeat: You see those as things that will make your games different. There was that mention of thousands of people in a battle royale game, instead of just 100.

Harrison: Yes. Now, whether it’s fun to have a 1,000-player battle royale was not the point. It’s more about the technical capability of it.

GamesBeat: How do you succeed in getting good people like that to work on this?

Harrison: I’ve been really happy with the team I’ve been building. More than half of my leadership team now comes from the game industry. We have some very seasoned talent. We have some great new passionate thinkers. It’s fun seeing the inside of Google that Sundar alluded to yesterday. There are a lot of passionate gamers who got into tech because of games. They work at Google. They’re now able to bring their talents to a game platform. It’s a win-win. It’s not just about hiring people from outside of Google. It’s also about finding those talents from inside.

Above: The Stadia controller from Google.

GamesBeat: As a game executive, do you feel like you need a certain amount of autonomy from the top? Sony managed, over many years, to have games as an island of executives, it seems, free from the interests of the other parts of the company. I heard someone at Amazon asked if they would set up their game business that way, and the response was, “No, we would not. We would operate as one company.” That person turned down the job, because they believed that in some ways, the game executives needed autonomy.

Harrison: Google has, rightly or wrongly, trusted me with a huge amount of autonomy to build this vision and tell this story. But I can’t do this on my own. What I love about Google is the collaborative nature of the company and the fact that I have partnerships all across the company, from YouTube to our technical infrastructure to Google Cloud to our hardware business, who are participating and partnering with us to make Stadia real. It’s not just my team. It’s a much broader team.

You saw, with Sundar as part of our presentation yesterday, that we have the support and investment from the top. But we do have the autonomy when we need it.