GamesBeat: As far as gamers go, it seems like it’s a tall order to convince them that there’s more to war that could be interesting than shooting things. I wonder how you’d successfully argue that.

Barron: It’s a fair point. It’s easy for me to sit here and say things, and it’s another thing to do it. But I’d say there are examples of games that have done that and have been fun. Even the action itself — what’s the definition of action? It doesn’t just have to be the reflex of clicking a button that’s the action. Action can take place in your head. Thinking about how I should approach a situation, that can be a form of action that’s directly to related to killing. That’s kind of the point. Even if you’re saying that what’s most fun is killing, ultimately — the thing that then leads to killing or an explosion. But even that can be made more complex and more realistic.

To give some practical examples, one of the most realistic war games, in terms of the combat aspect, was a game called Close Combat. The Marine Corps tried using it as a simulator. It was a top-down, 2D, real-time tactical game.

Above: Close Combat.

GamesBeat: Yeah, I played those games.

Barron: That, to me, probably still is the most realistic war game out there in terms of the actual fighting part. There’s a successor, Combat Mission, that’s also good, in 3D. A big part of the gameplay in that is — OK, there’s a house here. Does the house have somebody in it that’s going to shoot me? I don’t know. Maybe I should have my soldiers go around a different direction, so they’re not exposed to fire. Maybe I’ll shoot at the house even though I don’t know if anybody’s in it.

If you just want to get into the kinetics — that’s the term the military uses for when shooting is happening — even just the kinetic part can be made more realistic and still be fun. That’s what you see Arma trying to do. That’s what games like Close Combat do. The Total War series does that for ancient combat. Even that part, the killing part, can be made more realistic. But yes, it’s not for everyone.

GamesBeat: What do you think about a pro-war slant or an anti-war slant in games? Whether you notice that at all? When I look at books and movies, there are some interesting comments you can make on things like Apocalypse Now, where the overall intent may be to make an anti-war film, but there are parts you could as easily use for a recruiting campaign — like the “Ride of the Valkyries” scene. Do you see that in games, any kind of narrative slant that’s political?

Barron: A lot of it is in the eye of the beholder. Your example of the movies — I think another one, Team America: World Police, I’m surprised how pro-America people read that movie to be. A lot of soldiers, especially, thought that was meant to take a jab at this country, but a lot of people really love that “America, Fuck Yeah” song. If you’re inclined to go one way or the other, that’s how you’re going to perceive the media you’re consuming.

In general, the games out there — because they’re more focused on gameplay — I don’t see them as really taking an explicit stance as much. You do have some games that are meant to have a message to them. But given the focus on gameplay, you see less of that than in movies.

Above: Most of the action in This War of Mine is in multi-level buildings — the one you live in and the ones you salvage and trade in.

GamesBeat: You called out This War of Mine in a good way. Spec Ops was another one. What were your thoughts on those?

Barron: Spec Ops: The Line is interesting. There’s a lot of — it’s not a perfect example, but it gets called out by a lot of people. Not just me. They tried to do something really different. For that reason, it’s very interesting and illustrative. But you’re still killing a lot more people than you would in real life, right? The fighting is still cartoonish. A lot of the plot points are ridiculous. But at the same time, they’re trying to do something new and fresh. That’s why I think a lot of people take to it. It has a kind of anti-war message, and I know the intent of the creators — they were inspired by things like Apocalypse Now. But I’d say it’s fairly balanced in some ways. It’s not preaching at you. It’s flawed but very interesting.

This War of Mine I’ve actually not played, to be honest, but it came up in my research. I watched a lot of videos of it and was very intrigued. I’ve got it on Steam now, and it’s on my list. That one, I think, is — again, for me, it’s hard to call that pro-war or anti-war. For me, it’s just about the reality of it. It’s neither pro- nor anti-war to point to reality.

GamesBeat: It’s a side of war that we don’t usually see, perhaps?

Barron: Exactly. I read some of your articles that you wrote like the one about the experience of the Hiroshima atomic bomb in virtual reality. Would you consider that explicitly anti-war? It’s not explicitly pro-war. But it doesn’t have to be pro or anti. It’s explaining that this is reality.

GamesBeat: If you’re just pointing it out, reminding people, then sometimes, that’s enough. You don’t necessarily have to attach an explicit message to it. It seems like if you call out a side of things that people don’t think about much, a reminder of what happened, it’s enough of a message about war.

Barron: Sometimes, people have a straw man in their heads. If you start saying something, they project this on to you, that you’re this type of person. Either overly patriotic, flag-waving, pro-war, whatever, or a communist, anti-American hippie. If people don’t really listen to you, then they might be projecting some type of a message on you. I guess in general, I wish people would listen to each other more and learn from the experiences of others.

I found an interesting analogy. I was having a sort of Facebook debate with someone about — she was talking about cultural appropriation and her experience as a minority in the U.S. As we were discussing this, she said some stuff where I thought, “Whoa, that’s very similar to what I was just describing about being a veteran and trying to describe your experience to someone who’s not listening.” We have a lot of that around on many topics. We talk past each other instead of listening. It leads to bad decisions by a lot of people.

Above: An immersive war simulation.

GamesBeat: There are different kinds of stories about war that I find to be powerful. Elie Wiesel’s “Night,” his Holocaust memoir. It’s very spare in its description of everything. It just describes what happened to him. I find that’s powerful enough, memorable enough, for whatever message you want to send. I wonder if you’re hoping we get to some of this in games? It’s an older medium now, an older art form. If we want to say something important about a topic, what would you like video games to get to?

Barron: One of the powers of video games, the unique power, is it puts you in the place of — it immerses you. It lets you play a role in a way that watching a movie or reading a book doesn’t. It puts you in the role of someone who’s not you, and it can give you a set of choices. It can restrict you to the same choices that person would have in a given situation.

I used Crusader Kings 2 in my talk because I love that game. Playing that game, I’ve learned so much about medieval European history. It goes a long way to explaining a lot of things that make no sense when you just read about them. I’m in the role of a European noble, and I’m murdering my own son because he’ll be a weak heir. I can’t have my line propagated through him. You read about these kings killing off their families or whatever, and it makes more sense when you’re put in that situation. It doesn’t make it OK. It doesn’t mean you’re condoning it. But it helps you understand. Games can help us understand things in a way that’s more powerful than other mediums.

To the topic of war, it’s a very important subject. We don’t see this in America, but what we do has consequences. When we’re bombing Syria or bombing Iraq, it has real consequences for real people. It affects their lives, a lot more than it affects your life or my life. To me, that’s something that should be taken seriously. It shouldn’t be treated lightly. It’s a form of empathy. By experiencing these different sides of war, you might think twice before supporting it.

I’m not explicitly anti-war, but I do think we should think very carefully about what we get [involved] in. It does have consequences, and even the most just war is going to have bad consequences for the people who live where it’s fought. That’s why I ended my talk on that point. A lot of kids died out there. A lot of civilians. It wasn’t just the Taliban shooting civilians. We were doing it too. It’s unavoidable.

We want to think that it’s this sanitized thing, that war is pure good versus pure evil, and the good guys come in, and the civilians all cheer because the good guys are there to save them. That was not my experience. If you look around at all the places we’re involved in, that’s not the experience anywhere. We should be very careful about getting involved in places because it will have consequences. Maybe it’s still worth it. Maybe we still should be involved. But it will hurt some people very badly who shouldn’t be.

GamesBeat: Do you think the game industry could deliver a greater breadth of stories about war, these kinds of alternate narratives?

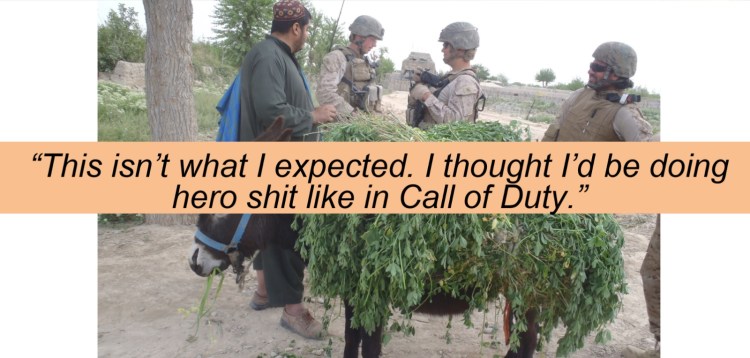

Barron: For sure. As an art form, certainly. This War of Mine is a great example of just showing a side that you wouldn’t normally see. Walking you through Hiroshima in VR is a great way of immersing someone in another side of the story. That’s one thing games can do. Another is to immerse you in what — I said it in my talk. We have an appreciation for the military, but we don’t really know what it is they do.

Even if you’re very pro-war — and I’m not saying I’m pro-war or anti-war — you should want to support the troops, and part of what that means is you should understand what their job involves. Maybe then you can help make their job easier or make sure their job is supported or maybe when they come home, you’ll better understand when you’re having that conversation and asking what it’s like. You’re not going to just cut them off and make it harder for them to integrate back into society. I don’t want to make this sound too anti-war, especially since my job is to support soldiers. But that’s a big part of it as well.