Andrew Barron knows a thing or two about war. He was deployed in Afghanistan in 2010, and he went on to train soldiers to use smartphone apps in combat zones. And now, he works as design director for Bohemia Interactive Simulations, which makes advanced military training simulations. The simulation, dubbed Virtual Battlespace, is powered by the game engine used to make the Arma military games.

That has given him perspective on realism in military simulations and video games, and he finds that the latter fall short because they’re mostly about nothing but shooting. He gave a talk at the recent Game Developers Conference (GDC) dubbed “Depiction of war in games: Can you do better?”

The military once led the development of war simulations, but now, it often creates simulations based on commercial video game technology. But Barron, who now works in Bohemia’s office in Prague, finds that games often fall short in the sophistication of narratives, as they often oversimplify complex conflicts. They also fail to depict the non-combat aspects of war that dominate a soldier’s life.

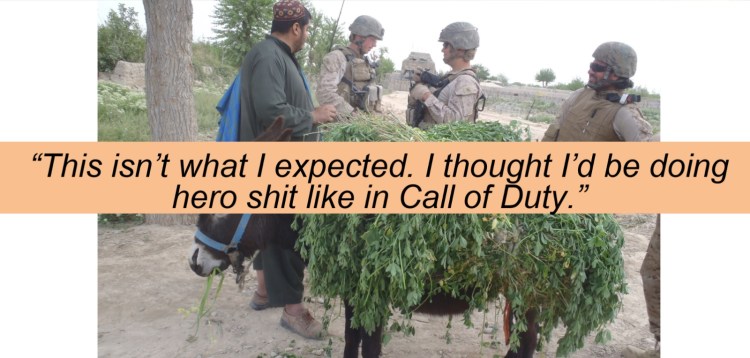

Above: War in real life: Andrew Barron in Afghanistan

He once heard a soldier say, “This wasn’t what I expected. I thought I would be doing hero shit like in Call of Duty.” I interviewed Barron, and he felt that game developers could become more knowledgeable about war, fleshing out games to be more realistic and engaging when it comes to storylines that balance the educational value with fun. He pointed out that the conflict in Afghanistan wasn’t just about the war on terror. It was also about age-old ethnic tensions as complex as Game of Thrones.

Games about war could point out moral ambiguity and ethical issues — like in Spec Ops: The Line. Soldiers often have to go through life-or-death decisions about whether or not to shoot at someone who looks like a civilian. Game narratives could also point out that “civilians pay the highest price,” he said. Some games have done that — like This War of Mine.

I’m not a veteran myself, and I have high respect for people like Barron. I have studied a lot of military history and wrote about anti-war literature in college. And so, I had a very interesting conversation with Barron about games and war and the responsibilities that game developers should acknowledge — and the need to employ veterans on game teams — when it comes to making entertainment about subjects with such gravity in the real world.

And for another take on war and games, check out this GDC 2015 panel on “Gaming the Laws of War: Can Real Consequences Mean Real Fun?”

Here’s an edited transcript of my interview with Barron. I do a lot of interviews. But I haven’t had a memorable and deep conversation about a subject like this in a while.

Above: Andrew Barron is a veteran and design director at Bohemia Interactive.

GamesBeat: I listened to your talk at GDC. It was very good. I wondered what kind of feedback you had gotten from people who listened to you.

Andrew Barron: I’d say that I’ve been — I didn’t know what to expect my first time giving a talk. I didn’t know how much feedback to expect. At the show, I got some positive feedback from people immediately afterward, which I really appreciated. Notably, a lot of veterans came up to me — at least three, maybe four — and said, “Hey, I appreciate the talk. I’ve been thinking about this for a while. I’m glad someone is up there saying this.” That, to me, was the most important feedback — not that the rest wasn’t. I’m glad they didn’t feel that I was misrepresenting them.

There’s been a couple of articles online, things like that. Journalists [have] been taking an interest, which has been interesting for me, seeing what it’s like to talk with journalists and see how they work. Overall, it’s been very positive.

GamesBeat: What years were you in the military and in Afghanistan?

Barron: I was in the reserves. I was never on active duty. I joined the reserves in 2002, and I left in 2011. I was activated and started training in the fall of 2010, and I was in Afghanistan about seven months in 2011, February to September. I got out of the military after I got back. I’d been in the military for eight years altogether at that point. I got out as a sergeant, the fifth enlisted rank.

GamesBeat: I’d thought about the topic for a while as well. I’m not a veteran or anything like that, but I did study war and history in college. I thought there was an interesting line that you pointed out between what’s realistic and what’s fun. What’s the difference between the two? What is the purpose of a video game? Is there a particular goal you have in mind as far as giving this talk and reminding people that games are not realistic, but they could be more realistic?

Barron: I’m not trying to tell people that they’re doing things wrong or that they have to stop doing things. I’d just like to be — the games industry is old enough and mature enough, both game players and game developers, that maybe we can expand the scope of the topics that we address and the way we address them in games. Especially with indie games, you see games taking on some very interesting topics that didn’t exist before — fatherhood, things like that. As an art form, it’s growing up and challenging itself. That’s part of it. I think we’re ready to move in that direction.

The other part is, it’s not as much about games but just as a culture, I wish we would be a bit more mature about war. Take it more seriously. Having been in the military since 2002 and having seen my country in a constant state of war — the saying, at least in the military and the Marine Corps, is that, “America is not at war. The Marine Corps is at war.” I think that’s pretty accurate. We have this low level of warfare that goes on forever. It’s not really discussed or thought about in sophisticated terms. That’s not all on the shoulders of video games, but at least, in part, it can be on the shoulders of video games.

Above: War can be like a video game.

GamesBeat: You addressed that in one set of slides where you pointed out that “hero shit” is such a small slice of the overall picture. Like having a movie about sex is a small slice of understanding about relationships.

Barron: That wasn’t made up. That was literally what I heard, that line about, “This isn’t what I expected. I thought I’d be doing hero shit like in Call of Duty.” I heard another Marine say that in Afghanistan. That stuck with me. It was part of the inspiration for the talk.

I think I mentioned in the talk that when I talk to people as a veteran — I’ve stopped really describing my experience in Afghanistan. The talk itself was very difficult for me to put together and prepare for and deliver because I had to think about some things I didn’t want to sort through. But it’s interesting to have a conversation with a civilian that hasn’t done any military history research, that’s not as sophisticated on the topic. That’s immediately where they go to in the conversation as well.

“How was it in Afghanistan?” I start talking about tribal conflicts and yadda yadda, and they cut me off. “No, what I mean was, did you see action?” That’s immediately what they jump to. Well, what do you mean by action? How do you define that? Hero shit like in the movies. It’s interesting to see — well, not interesting. It’s frustrating, in a way, how those conversations go. I generally just don’t have them anymore.

GamesBeat: I noticed that you were modding games before you went into the military. You were looking at war in video games and playing those games without direct knowledge. What did you notice between that time in your life versus afterward? What changed about how you view games?

Barron: I’d say I was always, from my teenage years, more interested in real military history. My dad was in the Marine Corps. My brother joined before me. I was always interested in the real story behind it. But certainly, after joining — you go through training. You see what is trained versus what isn’t trained, what they prepare you for. You have friends that go off to war, and you talk to them about it. They tell you their stories of what it was like. Even before you go yourself, you start slowly getting a picture of what it’s actually like.

This is where military simulations fall in because that’s what we do with simulations. We’re helping the trainers in the military prepare soldiers for what it will be like, which is why we need all these features that aren’t really useful in a video game. One thing I always found interesting, going from the modding world to the military simulation world — I’d go back to the forums for Arma or Operation Flashpoint, and I’d look at the discussions around what must be in VBS, our military simulator product. They were always just so off base. It was so interesting to see the difference between what they thought it must be versus what it actually was. These are people who are interested in more realistic games like Arma. They would already be a bit more sophisticated than the average gamer. But they’re still pretty far off from what the military actually needs.

GamesBeat: Did you find that anything in what you played, military simulations, actually served as training for you before you went? Prepared you for what it’s like, physically or emotionally?

Barron: Definitely. There’s a lot you can do without simulations, first of all, but certainly with simulations, it’s the next level. For example, we did a convoy simulator, the CCTT, Close Combat Tactical Trainer. This is old, old stuff, built in the early ‘90s I think, with really bad graphics. It’s actually a real Humvee you sit in, and there are screens around on the walls where it projects the 3D graphics. You have laser weapons you shoot at the walls. You have a steering wheel that really “drives” the Humvee. It’s like a really big arcade game, that type of simulator. Not a desktop trainer.

Anyway, we were practicing convoy operations, and it was incredibly helpful. Even immersive, surprisingly. The graphics were bad — really old, bad 3D graphics, much worse than what we have in VBS — but even that little bit, you felt immersed. We ran through a number of scenarios. We practiced different drills, reactions to contact, reactions to IEDs. All the stuff I have been doing professionally, building simulators, I got to be on the other side and use it. It worked. And these things were nothing compared to graphics of our modern games.

Above: Should this soldier shoot at this civilian on the bridge?

GamesBeat: It seems like the choices you might make in a Telltale game. I don’t know if Arma has some of this as well but distinguishing between who’s hostile and who’s not, what you should do. Are those kinds of games useful in some way, as preparation or education?

Barron: Another simulator that I used when I was in the military, one that’s very effective, is a marksmanship simulator. You have a projector and a gun with a laser in it, and you shoot at the screen. Again, it’s kind of like an arcade game, but imagine a whole wall that has these graphics projected on it. These are used by the military for marksmanship training. Police use these as well.

I was an operator, and I was also a marksmanship coach. I would train my Marines in these simulators. One of the best things they have is what are called “shoot/no shoot” scenarios. It doesn’t even need to be 3D graphics. It can be a real-life video recording of a situation where, OK, you’re on guard duty, and some guy is approaching your guard shack. He looks drunk, and then, he reaches into his belt and pulls out a gun. You can put soldiers in these scenarios and have them yell at the screen. “Hey, stop! Hey, shithead, stop! Put up your hands!” And you watch them through the whole scenario. What do I do? Do I yell at this guy? Point the weapon at him? Shoot him? Then, you can pause it at the end and replay it for him and talk him through it.

Telltale games give you these reactions. You have a limited amount of time to make a decision. That’s maybe an equivalent in the military simulations world. You have a limited amount of time to make an important [decision]. The controls are different, but it’s the same principle. Very useful for military training.

GamesBeat: So, in some ways, it can be done? You can teach civilians about war through video games?

Barron: I think you can do it through gameplay — like your example of the way it’s controlled in Telltale games. It can also be done through narrative, which is why I was talking at the narrative summit, through the way stories are told. Or, obviously, in games, it’s best with both. You have narrative together with gameplay, and you can make the best experience. It can be done with games, and I would argue it can be made fun. The narrative can be made interesting, and the gameplay can be fun.

GamesBeat: As far as gamers go, it seems like it’s a tall order to convince them that there’s more to war that could be interesting than shooting things. I wonder how you’d successfully argue that.

Barron: It’s a fair point. It’s easy for me to sit here and say things, and it’s another thing to do it. But I’d say there are examples of games that have done that and have been fun. Even the action itself — what’s the definition of action? It doesn’t just have to be the reflex of clicking a button that’s the action. Action can take place in your head. Thinking about how I should approach a situation, that can be a form of action that’s directly to related to killing. That’s kind of the point. Even if you’re saying that what’s most fun is killing, ultimately — the thing that then leads to killing or an explosion. But even that can be made more complex and more realistic.

To give some practical examples, one of the most realistic war games, in terms of the combat aspect, was a game called Close Combat. The Marine Corps tried using it as a simulator. It was a top-down, 2D, real-time tactical game.

Above: Close Combat.

GamesBeat: Yeah, I played those games.

Barron: That, to me, probably still is the most realistic war game out there in terms of the actual fighting part. There’s a successor, Combat Mission, that’s also good, in 3D. A big part of the gameplay in that is — OK, there’s a house here. Does the house have somebody in it that’s going to shoot me? I don’t know. Maybe I should have my soldiers go around a different direction, so they’re not exposed to fire. Maybe I’ll shoot at the house even though I don’t know if anybody’s in it.

If you just want to get into the kinetics — that’s the term the military uses for when shooting is happening — even just the kinetic part can be made more realistic and still be fun. That’s what you see Arma trying to do. That’s what games like Close Combat do. The Total War series does that for ancient combat. Even that part, the killing part, can be made more realistic. But yes, it’s not for everyone.

GamesBeat: What do you think about a pro-war slant or an anti-war slant in games? Whether you notice that at all? When I look at books and movies, there are some interesting comments you can make on things like Apocalypse Now, where the overall intent may be to make an anti-war film, but there are parts you could as easily use for a recruiting campaign — like the “Ride of the Valkyries” scene. Do you see that in games, any kind of narrative slant that’s political?

Barron: A lot of it is in the eye of the beholder. Your example of the movies — I think another one, Team America: World Police, I’m surprised how pro-America people read that movie to be. A lot of soldiers, especially, thought that was meant to take a jab at this country, but a lot of people really love that “America, Fuck Yeah” song. If you’re inclined to go one way or the other, that’s how you’re going to perceive the media you’re consuming.

In general, the games out there — because they’re more focused on gameplay — I don’t see them as really taking an explicit stance as much. You do have some games that are meant to have a message to them. But given the focus on gameplay, you see less of that than in movies.

Above: Most of the action in This War of Mine is in multi-level buildings — the one you live in and the ones you salvage and trade in.

GamesBeat: You called out This War of Mine in a good way. Spec Ops was another one. What were your thoughts on those?

Barron: Spec Ops: The Line is interesting. There’s a lot of — it’s not a perfect example, but it gets called out by a lot of people. Not just me. They tried to do something really different. For that reason, it’s very interesting and illustrative. But you’re still killing a lot more people than you would in real life, right? The fighting is still cartoonish. A lot of the plot points are ridiculous. But at the same time, they’re trying to do something new and fresh. That’s why I think a lot of people take to it. It has a kind of anti-war message, and I know the intent of the creators — they were inspired by things like Apocalypse Now. But I’d say it’s fairly balanced in some ways. It’s not preaching at you. It’s flawed but very interesting.

This War of Mine I’ve actually not played, to be honest, but it came up in my research. I watched a lot of videos of it and was very intrigued. I’ve got it on Steam now, and it’s on my list. That one, I think, is — again, for me, it’s hard to call that pro-war or anti-war. For me, it’s just about the reality of it. It’s neither pro- nor anti-war to point to reality.

GamesBeat: It’s a side of war that we don’t usually see, perhaps?

Barron: Exactly. I read some of your articles that you wrote like the one about the experience of the Hiroshima atomic bomb in virtual reality. Would you consider that explicitly anti-war? It’s not explicitly pro-war. But it doesn’t have to be pro or anti. It’s explaining that this is reality.

GamesBeat: If you’re just pointing it out, reminding people, then sometimes, that’s enough. You don’t necessarily have to attach an explicit message to it. It seems like if you call out a side of things that people don’t think about much, a reminder of what happened, it’s enough of a message about war.

Barron: Sometimes, people have a straw man in their heads. If you start saying something, they project this on to you, that you’re this type of person. Either overly patriotic, flag-waving, pro-war, whatever, or a communist, anti-American hippie. If people don’t really listen to you, then they might be projecting some type of a message on you. I guess in general, I wish people would listen to each other more and learn from the experiences of others.

I found an interesting analogy. I was having a sort of Facebook debate with someone about — she was talking about cultural appropriation and her experience as a minority in the U.S. As we were discussing this, she said some stuff where I thought, “Whoa, that’s very similar to what I was just describing about being a veteran and trying to describe your experience to someone who’s not listening.” We have a lot of that around on many topics. We talk past each other instead of listening. It leads to bad decisions by a lot of people.

Above: An immersive war simulation.

GamesBeat: There are different kinds of stories about war that I find to be powerful. Elie Wiesel’s “Night,” his Holocaust memoir. It’s very spare in its description of everything. It just describes what happened to him. I find that’s powerful enough, memorable enough, for whatever message you want to send. I wonder if you’re hoping we get to some of this in games? It’s an older medium now, an older art form. If we want to say something important about a topic, what would you like video games to get to?

Barron: One of the powers of video games, the unique power, is it puts you in the place of — it immerses you. It lets you play a role in a way that watching a movie or reading a book doesn’t. It puts you in the role of someone who’s not you, and it can give you a set of choices. It can restrict you to the same choices that person would have in a given situation.

I used Crusader Kings 2 in my talk because I love that game. Playing that game, I’ve learned so much about medieval European history. It goes a long way to explaining a lot of things that make no sense when you just read about them. I’m in the role of a European noble, and I’m murdering my own son because he’ll be a weak heir. I can’t have my line propagated through him. You read about these kings killing off their families or whatever, and it makes more sense when you’re put in that situation. It doesn’t make it OK. It doesn’t mean you’re condoning it. But it helps you understand. Games can help us understand things in a way that’s more powerful than other mediums.

To the topic of war, it’s a very important subject. We don’t see this in America, but what we do has consequences. When we’re bombing Syria or bombing Iraq, it has real consequences for real people. It affects their lives, a lot more than it affects your life or my life. To me, that’s something that should be taken seriously. It shouldn’t be treated lightly. It’s a form of empathy. By experiencing these different sides of war, you might think twice before supporting it.

I’m not explicitly anti-war, but I do think we should think very carefully about what we get [involved] in. It does have consequences, and even the most just war is going to have bad consequences for the people who live where it’s fought. That’s why I ended my talk on that point. A lot of kids died out there. A lot of civilians. It wasn’t just the Taliban shooting civilians. We were doing it too. It’s unavoidable.

We want to think that it’s this sanitized thing, that war is pure good versus pure evil, and the good guys come in, and the civilians all cheer because the good guys are there to save them. That was not my experience. If you look around at all the places we’re involved in, that’s not the experience anywhere. We should be very careful about getting involved in places because it will have consequences. Maybe it’s still worth it. Maybe we still should be involved. But it will hurt some people very badly who shouldn’t be.

GamesBeat: Do you think the game industry could deliver a greater breadth of stories about war, these kinds of alternate narratives?

Barron: For sure. As an art form, certainly. This War of Mine is a great example of just showing a side that you wouldn’t normally see. Walking you through Hiroshima in VR is a great way of immersing someone in another side of the story. That’s one thing games can do. Another is to immerse you in what — I said it in my talk. We have an appreciation for the military, but we don’t really know what it is they do.

Even if you’re very pro-war — and I’m not saying I’m pro-war or anti-war — you should want to support the troops, and part of what that means is you should understand what their job involves. Maybe then you can help make their job easier or make sure their job is supported or maybe when they come home, you’ll better understand when you’re having that conversation and asking what it’s like. You’re not going to just cut them off and make it harder for them to integrate back into society. I don’t want to make this sound too anti-war, especially since my job is to support soldiers. But that’s a big part of it as well.

Above: Arma.

GamesBeat: It seems like there are some very different conclusions you could draw. In some ways, the realistic military simulations like Arma are a good thing to have, but something like, I don’t know, Saving Private Ryan can be a good thing as well.

Barron: I think the truth is a good thing to have. You can’t go wrong with doing good research about what actually happens and trying to represent it as accurately as possible. Whether it’s a movie like Saving Private Ryan or a VR experience about Hiroshima or a game like This War of Mine. There are all different views, and maybe they have different slants, but it doesn’t hurt anybody to look at things the way they are, even if it’s only a part of it. There’s nothing wrong with having different perspectives. That’s what games can do. They can provide different perspectives.

GamesBeat: Do you think about how to apply some of this high-level thinking you have about war to particular [kinds] of games that you might want to work on in the future?

Barron: I have my side interests. I like board games. I’ve been working on a board game that’s a kind of cross between a hack-and-slash dungeon crawl and an Afghanistan-set war game. I think I talked about this in my talk. War is more like an RPG. I think it would be an interesting way to approach and experience this, whether in a board game or a video game. Take more cues from the way RPGs work — the way they tell stories and let you interact with the game world — and apply that to a more action-oriented, more modern warfare-oriented context. I think that would be interesting to see.

GamesBeat: Are there memorable moments that you remember from games and their treatment of war, things you still think about?

Barron: Operation Flashpoint, obviously. That game changed my life. I wouldn’t be here in Prague talking to you if it weren’t for that game. In many ways, it’s had a huge impact on my life. Before I started doing anything professionally, it was because the game itself wrapped me up. I remember playing the demo in 2000, 2001, where you gathered a squad of AI soldiers and went up a hill and there’s an enemy BMP that you shoot with a rocket. You’re in this huge world, and stuff is going on everywhere. It was just mind-blowing, that it could be done in a video game.

I remember a sequence with a truck. I shot the truck driver, and then, I was able to get in the truck and drive it. I just drove it around the world until it ran out of gas, hours of wandering around this giant terrain. That really opened my imagination as far as what you could do in video games with war as a setting. That’s when I really got into modding. I had all of these things I wanted to do, all of these gameplay elements I wanted to explore, levels I wanted to make. That game consumed my life for years. Then, I got hired at Bohemia, and it’s consumed my life ever since. That’s the most memorable.

Above: Turning signals on convoy vehicles are critical in proper simulations, but game devs might overlook them.

GamesBeat: When you’re working at Bohemia, is there an interesting dynamic between you as a veteran and younger people who’ve always been software developers?

Barron: There’s an interesting cultural dynamic in general, America versus Europe in general, but especially the Czech Republic. America is very patriotic, let’s say, very support-the-troops, very thank-you-for-your-service. Over here, it’s not seen in the same light. It’s not that people dislike it, but it’s not held in as high of esteem over here, the concept of the military. In the U.S., it’s one of the institutions that’s held in the highest esteem compared to anything, but over here, it’s not so much up there.

In general, there are not a lot of veterans in games, in development. Even in the simulations industry, on the development side there are very few veterans. I don’t hide, but I’m not walking around trying to advertise it everywhere I go. When it comes in handy, and it does quite often, I’ll use my experience to explain. We’re doing military simulations, so obviously, there are many times where we’re working on some features, and I’m able to explain it to the developers in a way that makes sense. “This is what this will be used for. This is how it works in real life. This is the implication.” That’s more useful, that ability to explain things in a developer’s terms. This is what this means to you as a developer, how this impacts your work. I think that’s where I bring value to this company specifically or one of the ways I bring value.

GamesBeat: In some way, your job seems consistent with the message you want to get out there. You’re at a company that does realistic games.

Barron: I hope so. I hope that gives me some credibility. All I do all day is make video games that are used to train soldiers to go to war, and now, I’m on the simulation side. It’s actually two separate companies. The simulations company, we take the game engine and do that, and then, there’s a separate company that takes the engine to make commercial games. But they have a similar philosophy of making them as real as possible. It’s about showing things the way they really are.

When I talk to military customers, it’s a completely different conversation than talking with civilians. We’re talking about real things that they need to prepare for in different kinds of military operations. On the game side, it’s so far removed from that conversation.

Above: Are there any threats within view?

GamesBeat: In some ways it almost seems like, in those simulations, you need the boring parts because that’s the way it is. When you’re surprised by something you can be legitimately surprised.

Barron: The way that the military uses simulations, it’s interesting. It’s more like a role-playing game. You have an instructor, and he has a sort of god mode. He’s almost acting like the dungeon master in a pen-and-paper RPG. He’s watching from a bird’s-eye-view camera. He has a special interface. He watches what the trainees are doing, and in real time, he makes something happen. A bomb just exploded next to you. What do you do? He can take his mouse, place an IED, make it go off, and then watches what the trainees do.

One of the differences between games and simulations is the simulations don’t have levels. All the levels are created by the instructor, so every training event is a new level. The trainer acts as a game master running the level in real time, so it can be adjusted according to what the trainees are doing. That’s not a game mode you usually see in video games, although Arma has the Zeus DLC, which is pretty much just that.

GamesBeat: Based on the experience of giving the talk and the feedback you’ve gotten, what would you say is your conclusion? What do you think you’ve learned from it?

Barron: I learned that writing is hard [laughs]. I was torn on whether to do a design talk or a narrative talk, but I’m glad I decided to do a narrative talk because I had to think of this from more of a narrative perspective. I have a new appreciation for how hard it is to write in a speech format. I can’t imagine a game format. It has to be a lot harder.

As far as my takeaway or my message, it’s that games can do more. Games can grow up. Game audiences — there’s room for mature themes and a bit more thinking and a bit more intriguing, deep narrative and deep gameplay. Games can do that. Games can learn a lot from the military and also from military simulations. We’re making games to train real-life soldiers. It’s not hard to take those techniques and apply them to video games.

I’d also say, this is something I didn’t talk about as much in my pitch, but I’ve encouraged more veterans to get involved in game development. That’s another way to get these voices out there. When we’re hiring, I always give bonus points to veterans, but there aren’t a lot out there that have development skills. Maybe some of them don’t know if there will be a cultural fit. But I’d say, please join us, and help us out.