testsetset

Is the next $10 billion game company acquisition right around the corner, or have all of the investors and acquirers moved on the more fruitful markets of Bitcoin, cryptocurrency, and blockchain?

Gaming has been around for a while, and it has grown into a $116 billion industry, according to market researcher Newzoo. It continues to have a rich cycle of startups, which grow up to disrupt bigger companies and then are acquired by the master strategists. Platform companies hover over the market, as they see gaming as a key to making their platforms more popular. Many different reasons drive acquisitions. So will game company mergers and acquisitions rise or fall?

I moderated a panel on that topic of acquisitions in the game industry at Casual Connect USA 2018 in Anaheim, California. The panelists included Scott Rupp, U.S. managing director for Modern Times Group; Shanti Bergel, executive vice president at FunPlus; Michael Chang, senior vice president for corporate development at NCSoft West; and Chris Heatherly, executive vice president of games and digital platforms at NBCUniversal.

AR, VR, and games adviser Digi-Capital estimates that game investment topped $2 billion in 2017. And games M&A in 2017 fell below $5 billion to its most recent low point of 2015 due to a lack of giant games acquisitions in 2017 (unlike 2016’s record of over $28 billion). Digi-Capital reported that the games IPO market rebounded to a record high last year led by Netmarble, SEA (Garena), and Rovio.

Here’s an edited transcript of our panel.

Above: The crowd at Casual Connect USA 2018.

Scott Rupp: I’m the U.S. managing director for Modern Times Group, which is a publicly-traded European media company based in Stockholm, with about $2 billion in revenue and a $3 billion market cap. A third of our business is digital, and the balance is TV. Within digital we’re very active in gaming, esports, and digital video. In gaming we own Kongregate and InnoGames, and in esports we own ESL and Dreamhack.

Shanti Bergel: I’m the EVP for a company called FunPlus. FunPlus was a startup. We raised about $75 million in venture capital, and then had an exit event. We sold, in an asset sale, our casual games division for $1 billion to a Chinese company in 2016. We still retain our mid-core game portfolio, and we’re a fully independent company now. The asset sale liquidated our investors. The entire company is now owned by the two founders.

We have our mid-core game portfolio, which includes a game called King of Avalon, which is one of top 20 grossing games in the world. We’re now investing in other companies in an area we call digital entertainment, which includes games, but isn’t limited to them. For example, we’re an investor in an esports team called Cloud 9, and we’re investor and part operator in a mobile streaming company, as well as some other content plays in digital entertainment.

Michael Chang: I work at NCSoft, one of the world’s largest publicly traded game companies. We’re best known for PC MMOs, but recently we’ve had success with mobile products. The mobile Lineage, which launched in Korea alone, did about $700 million in six months. I do investments and acquisitions for the company. We’re looking for people to back. Before this I used to do M&A for Electronic Arts, along with Shanti here.

Chris Heatherly: I’m EVP of games at NBC Universal. We’re out of the Universal Studios group. I came to Universal to help transition our model from primarily licensing over to publishing. I spent the last year building a team and working with developers in order to develop games with our IP that we can publish. In addition to that, I advise, within the company, on other things that touch the games industry – things like VR, esports, investments through things like Comcast Ventures. I touch all of those things, at least as an advisor.

Above: DLink showed off wireless VR via WiGig technology.

GamesBeat: This is about acquiring game companies. Earlier this morning, Eric Goldberg moderated the session on investing in game companies. I was curious what you guys think about what’s hot for investments now, particularly because that’s the beginning of the eventual acquisition process. We’ve gotten a good sense that VR is cooling down, but esports is heating up. That’s the general vibe. Scott, did you have any other takeaway from that session?

Rupp: Certainly esports is hot. As we think about areas to invest in for our venture fund, it is focused on esports and gaming. We’re interested in certain sub-themes within those categories. In esports we’re looking at mobile esports and analytics and analogous pieces to other pieces of the traditional sports ecosystem.

For gaming, we think there’s a huge hole in the market to back developer-publishers. There’s a lot of value to be created there. There’s a healthy VC market in Europe, but not as many active investors here in the states. We see a gap there. But we’re looking at every evolution in publishing. We’re looking at alternative ways to drive discovery, alternative ways to finance games, alternative ways to market games. There’s a lot of fertile ground across the space.

Bergel: Our take on investments — at a very high level, in terms of maturity, mobile for example is quite mature. We’d be more likely to acquire proven quantities in mobile than we would in an environment like instant gaming or games for voice on Echo or Google Home. Those are areas where we see people attempting to build new businesses now and it’s an interesting place to invest.

Typically, as an investor, you think about the early stage, where new markets might grow, but we’re not quite ready to jump in there with our internal development studios, which are committed to more mature businesses. For example, King of Avalon, that’s a standing dev team of some size. We can’t easily just take them off that, because it’s a very large revenue driver for us. It’s incumbent upon us, if we want to participate in some of the new platforms that are up and coming, to work with folks that are outside the company and invest in their ideas and try to identify places where we can be helpful to people who are developing what might be a next-generation business.

Chang: By a show of hands, how many of you would be excited to start a new mobile gaming company now? Just a few hands. That’s boundless optimism there. Number two, how about starting a new PC or console game studio? Facebook instant games? Games for Amazon Alexa or Google Home? Interesting. How about AR? Mixed reality? Pretty brutal right now. It’s an interesting indication.

I think there’s an interesting dynamic going on here. The gaming market have never been larger since I joined in 2010. Everyone’s a gamer. Everyone has a phone right now. But the opportunities for independents are a lot more interesting, shall we say, than when we started these conferences in Seattle. In 2010 there were all the games from Big Fish, all the PC client downloadables. That’s all gone to Facebook and free-to-play mobile. New Xbox, new PlayStation, VR came and did one of these. We’re all looking for something in AR, Facebook Instant, audio games.

These are the biggest markets ever, but it’s also the most challenging. We’re all looking for the new area. We don’t have that next platform. It’s changing the dynamics of what kinds of deals we do right now and the types of things people should be working on, at least in the short to medium term.

Above: VY Esports wants to match brands and esports events.

Heatherly: I’m a little more bullish. I feel that the investor community is ultimately too bearish on the whole market. It’s the biggest, most monetized game market that there’s ever been. Everyone in the world is playing games now. If you look at companies like Playrix, there are probably four or five new entrants in the top 20 grossing every year.

I think the challenge with free-to-play games on mobile is that there are very few people that are going to do it well. You have to do a lot of things right. You have to build the infrastructure. The investments are significant, and then there’s the UA expense. Good teams that are good at free-to-play are breaking through and making a lot of money. But that’s an admittedly small number of companies given the difficulty factor.

The Instant Games market is very interesting, although I worry about the — there’s going to be a lot of casualties there if the platform dies. Facebook is going to make the economics challenging. How many people here have played Facebook Instant Games? What’s driving the market is what drove the early Facebook web games. If Facebook ever throttles back the virality like they did on Canvas they can kill that market overnight, which has to make one a little bit nervous.

Long term, even VR, I’m not ready to count that out. It’s going to be several years, but people just need to buy headsets. The barrier to entry, the cost, the complexity of systems—when we start getting into six degrees of freedom and wireless headsets, we’ll start to see if that’s a market or not. But there are more ways to play games than ever before, and new ways to make games are being invented, like HQ. For those who haven’t seen it, HQ is a game show that’s livestreamed. These guys are getting more than a million concurrent players right now, MMO-sized numbers. The appetite for games is endless. The challenge is in marketing and user acquisition, but there’s no better time to make games, in my opinion.

Bergel: Just to nuance that point, I agree that there are amazing opportunities in the space. However, if you look at the companies that are making conventional plays, Playrix is an old company. It’s not a company that came in last year and jumped to the top of the charts. The presentation right before we came on, about Game Insight—a super compelling story, the success of Guns of Boom. But Game Insight is also not a new company. Our company was founded in 2010 and we had a huge exit. But we’ve been working at this for a long time.

To start a mobile game company right now, as an investor, I would worry about that. I would think, okay, how far do you have to go to be market competitive with the people who are up here right now? What are you bringing to the table? If you used to work at Supercell or EA or Machine Zone, those are all good things, but how fast can you come up to speed from a live ops perspective and beat the guy next to you?

Chang: We have to be very creative now. Whether it’s influencers or esports, creating something to drive discovery, or something to drive more customer acquisition, we have to be very clever now. We have to have some unique differentiation. We’re having to be stock pickers, versus just betting on the stock market.

Above: Dan Fiden, chief strategy officer at FunPlus.

GamesBeat: I interviewed Dan Fiden back in February of 2016. I’m curious how some of the thinking may have changed since then. At the time he was saying everyone else was swimming in the same direction, into new platforms that have zero penetration like VR. He wanted to take his $50 million fund and invest it in mobile games. But it seems like now that’s not an automatic strategy for you guys.

Bergel: In 2016 that was more of a reasonable thing to say. But even so, it is being said from the point of view of a company that has a lot of resources to bring to bear. Why would you take money from FunPlus in 2016? Because we know a lot about certain aspects of the mobile market. We can add a lot of value from an operations perspective. What a lot of western developers are missing when they come to this market — there’s an understanding of LTV, an understanding of live operations, an understanding of how to arbitrage CPI and LTV effectively. Those are things that FunPlus, in an internal analysis, thought we could bring to bear as far as being a good partner to companies that might be coming up.

Full disclosure, everyone who came through that door got measured alongside the same criteria we’d use for an internal studio. It’s a competitive filter. It’s not an act of charity to establish a $50 million fund and say, “Hey guys, let’s go make some games.” The investment criteria for a nascent category are much more relaxed. It’s much more about exploration and R&D. Whereas in a fully developed category, where we can see all the numbers on AppAnnie, it’s a different thing. That’s why we as a company look at acquisition for that bucket as opposed to investment.

GamesBeat: One point is that this is a very fast-evolving thing. Your thinking in different sectors is often changing.

Bergel: For sure. Two year is an eternity in mobile.

Chang: To that point, in gaming right now, people capture very quickly. I grew up in the world of venture capital, where you’re trying to invest in small, but rapidly growing markets, so when the larger guys come in you can defend that position.

We talked about Facebook Instant Games today. Zynga is there. They haven’t missed this one. They have Words with Friends in there. There are large guys in that market, because they’ve seen the virality that they remember from the Facebook Canvas days. They’re not seeing the retention, but they’ll see ad monetization and in-app purchase monetization coming up. They’ll see combinations of chat bots and other things that make games more immersive.

We’re asking and encouraging you, because we’re all investors here, to find those undiscovered and untapped markets, where you can be a leader in a small, but ideally long-term market in the future. If you can find those and defend that position, you’ll have something of great value that someone can pay you for or fund you for in the future.

Above: Pitchbook’s list of the biggest game and gambling industry deals.

GamesBeat: Chris, you know about changing patterns in the business from your previous experience at Disney. There’s almost a cyclical pattern to Disney’s interest in games.

Heatherly: For entertainment companies, our view at Comcast Universal is that Comcast started off as a cable company. It’s become a broadband company. The people in the company know what’s going down those pipes is what’s growing broadband views. Some of it is streaming video, but a lot of it gaming. We have a management team that has a very progressive view toward the games business.

We’re heavily invested in traditional media assets already. We have a lot of capital, but we’re in search of something new. One of the things that I think is attractive to our company is that games are adjacent to both the things we do in the cable business and the things we do in the entertainment side of the business. It’s a new media business we’ve found. That’s the opportunity for us.

GamesBeat: I like to get a handle on just how many acquisitions are happening and how many dollars are going in every year. I used to track that back in 2011-2012, and then Digi Capital picked it up. Pitchbook has some material, but they don’t publish it very often. We’re left a bit in the dark as to where the trends are going with acquisitions in the game industry. Is it going up or going down?

Chang: Let’s ask the audience. How many of you can name a major acquisition of a game company in 2017?

GamesBeat: EA acquired Respawn for $455 million.

Chang: Nexon acquired Pixelberry. How many of you know what Pixelberry is? Targeting a demographic of women with story-driven games. They’re expanding an audience. It’s quite a sizable company. But any other major acquisitions? Exactly.

GamesBeat: The interesting thing was those were the same week. The same bidders were going for both companies.

Chang: If we were talking about 2016 I bet there would be a lot more names out there, or 2015. Remember the times of Playdom and Playfish, when all the Facebook games were getting acquired.

Above: A sign of Tencent is seen during the fourth World Internet Conference in Wuzhen, Zhejiang province, China, December 3, 2017.

GamesBeat: One thing Pitchbook does have is their list of the biggest deals. The biggest deal of all time in games is Tencent putting money into Supercell for most of it, when it had a $10.2 billion valuation in mid-2016. Disney only paid $4 billion to buy Lucasfilm. It’s an interesting number to compare. Activision paid $5.9 billion for King. IGT got acquired for $4.7 billion. Mojang for $2.5 billion. We have some real numbers here. I suppose you guys don’t feel like you’re in the wrong sector as far as activity.

Rupp: It certainly feels very active in the deal markets. Maybe there aren’t as many big fish to go after anymore, but there are a lot of attractive, profitable, growing companies in the $20-100 million revenue range. All those processes are quite competitive, but the pricing is still quite reasonable. You have to win. You have to outmaneuver others. But there’s a lot of action and a lot of opportunity to create value still.

Chang: The way things worked doing M&A in 2010 and 2013, basically, if you didn’t do it, Zynga would do it. It felt very much like you had to do it, or you would lose an opportunity. The good news, at least from this perspective, is that there’s time for due diligence, time to do work and find the right companies.

I’d say the good news for this audience here as well — back in 2010 and 2011 people were joining the business because it was the flavor of the month. They wanted to go into the hot area. I like how things are now, because people who are in the space — it’s not the easiest area, so these are people who are dedicated to games. I enjoy working with real game developers, people who are passionate about making games, seeing their products out there, seeing people playing and enjoying them.

It’s a give and take here. We have time to do more work, to look for real and meaningful companies. You get the chance to build good and meaningful companies and have fun doing it, without having a lot of money running around just because the business is hot.

Bergel: That’s right. I think a lot of those early, old exits were companies that were not solid yet. They were probably bought for values for too high. They burned a lot of acquirers and killed the interest for a little while. But I see that as an opportunity. Where we specialize is working with small to medium-sized developers who have good teams, but are looking for a way to break through in the app store. We have IP and access to the database of customers from across the company. We can connect game makers with our data and the properties we have. We’re in a very unique situation to help some of these guys who are maybe not getting the exit, but we can help them break through and get to the next level.

GamesBeat: Why aren’t you guys all going into cryptocurrency and Bitcoin mining?

GamesBeat: Why aren’t you guys all going into cryptocurrency and Bitcoin mining?

Chang: It’s funny that no one brought that up. How many of you think cryptocurrency is an interesting area for gaming? Did any of you play Crypto Kitties? [laughter] We just had Brian Fargo on from inXile. Those are new opportunities. We have to figure out if there’s something real to be had there. But that’s potentially a new area of growth. In the existing areas, there’s still no leader in racers or shooters. Let me take one aside here. In general, EA, Activision, Take-Two, they haven’t launched a linear racer or shooter in a while. Is there still opportunity there? I think so.

When I was at EA, Disney bought Lucas. In the announcement, Disney talked about the movies and Star Wars and Lucasfilm and Skywalker Sound, but they didn’t say anything about the game studios. The Lucas games guys all said, “Hold on, are we going to have jobs?” It turns out that led to this question internally at EA that bubbled up, which led to the licensing deal that created Star Wars: Galaxy of Heroes, Battlefront, Battlefront II.

In these sorts of big deals, there are opportunities for everyone. Disney has reportedly signed a deal with Fox that’s going to take some time to play out. Could you do something with that? What could you do with that? I like to point out areas of opportunity that might not be immediately obvious, but there might be something that one of us could play on.

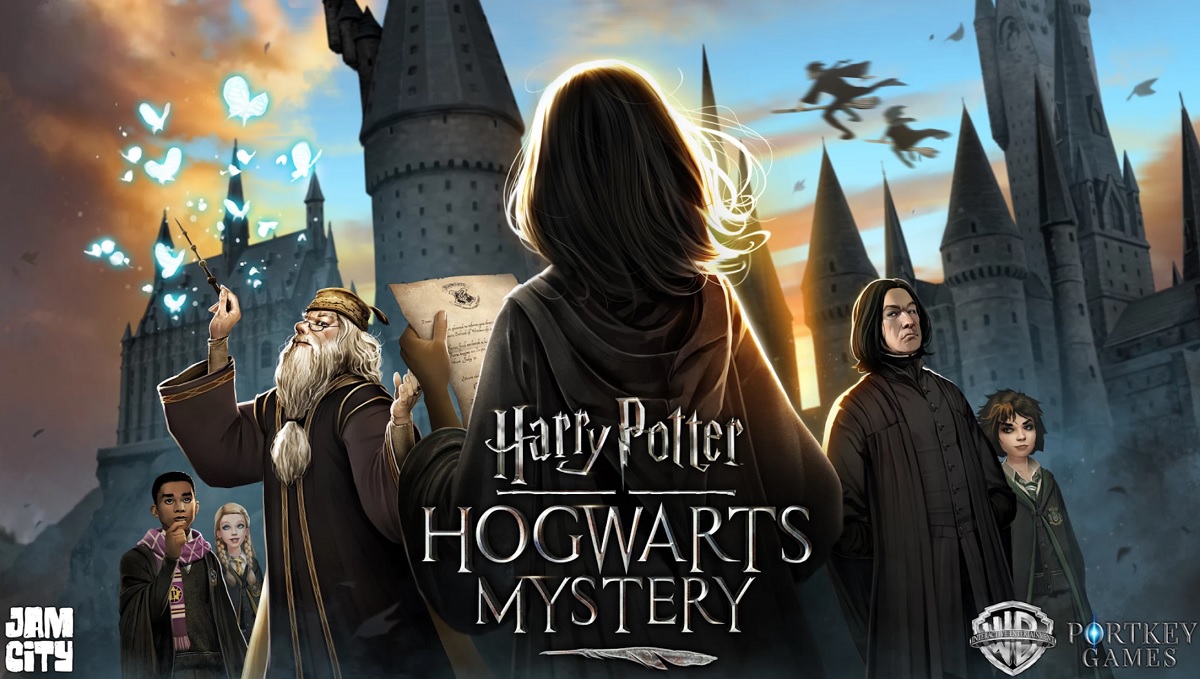

GamesBeat: There’s this idea that some franchises come and go, or rise and fall. It’s interesting that in 2018 we may get two Harry Potter games on mobile, one from Niantic and one from Jam City. The Jam City folks said, “We’re attracted to this because there hasn’t been a big Harry Potter game on mobile yet.” The opportunities seem to materialize sometimes.

Heatherly: What I think is interesting when we talk about IP is that if you look at almost every major franchise, what you see is one game that’s really big, and then three or four games that are pretty small. The one game is almost always around 70 percent, and then the other 30 percent is divided up. If you’re Marvel, and you’re the biggest brand on mobile, that 30 percent can still be something pretty meaningful. If you’re smaller, that 30 percent is a challenge.

Part of that, I think, is an artifact of the licensing model. What’s happened is that when you license five different companies with five different games, one of them ends up with higher LTV, and they beat the other guys on Facebook with user acquisition instead of cross-promoting across the network, which is the way King and Playrix these guys get big. We’re trying to build our network and use the success of one game to drive the success of the next game. We’ll see how it works, but that’s our operating theory.

It’ll be interesting to see what happens with something like Harry Potter that’s got two games. Do they both find an audience or does one win out?

Chang: To talk some more about what Chris is saying, let’s pick on Marvel for a minute. Let’s be careful, because I’m a huge Marvel fan and I’d like to get something from them someday. [laughs] But can you name the Marvel titles out there in mobile right now, all of them? Future Fight, Puzzle Quest? Are the old DeNA games still out there? I don’t know. One game, Kabam’s Contest of Champions, has the highest LTV. If they can spend on Facebook and buy more fans of Marvel than anyone else, maybe you shouldn’t have so many licensees out there.

Above: Jam City will let you attend the school for magic in Harry Potter: Hogwarts Mystery.

GamesBeat: The two Harry Potters seem to be in pretty different categories, though.

Chang: That’s what they all say. One’s a city-builder, one’s more like Clash Royale — that kind of genre differentiation will be key.

What do you think is the best, most valuable license right now on mobile? If you could get a license in mobile right now for a reasonable price, what IP would you chase? What do you think is popular right now? I’d like to hear from the audience. Star Wars? Pokemon? I bought the studio that made Simpsons Tapped Out. It’s been a long time since there’s been a new Simpsons game. Family Guy? Has anybody seen a movie title that’s become a top-grossing title, a very successful title? Me either. That’s interesting.

Bergel: The problem with movies is that you can’t drive a free-to-play game with just one movie. Star Wars can work, or something like Fast and Furious can work.

GamesBeat: Some of the VCs out here may be looking to you guys for some guidance as far as what you’re interested in. That’s one question. The second question is, who do you look to for guidance? Do you look to Hollywood companies, IP holders? Do you look to platform owners? First question first, what should venture capitalists learn from your actions as far as where they should be thinking about investing?

Rupp: For us, we’re maybe a little different from some others. We have a bit of an aversion to licensed IP. Mostly because we’re a broadcaster that licenses a lot of IP for television. Every year we grow the audience and pay more for rights, which is a tough model. So we have a bias toward companies that own their own IP. That’s what we’re looking for, for the most part, when we’re buying game companies.

Above: Slashy Hero is Kongregate’s first Steam game.

GamesBeat: Kongregate makes sense for you there, then?

Rupp: Kongregate obviously publishes titles and has licensed IP games, but part of the strategy there is to start owning more studios. We’ve been rolling up new studios under the Kongregate umbrella, so the mix of first-party titles increases over time. Owned IP is big, and we’re also looking for — this may sound boring, but we want sound businesses. Things that are just hot — we’re happy to be late to certain sectors on an M&A transaction if that means we pay for a company that’s working. Our VC approach is very different, obviously.

Bergel: I have one comment that ties back to the IP conversation. Probably the most interesting — I’m not yet sure that this is exciting, but the most interesting IP deal I saw recently was between Skybound and a mobile developer called Gamevil. Skybound is going to create a whole world of transmedia properties around Gamevil mobile IP.

To me that was a very interesting difference in the way that these two companies decided to come together to create something. They’re trying to fuse the clear business potential of mobile, which is well-established at this point, with the storytelling capabilities at Skybound, which if you don’t know was founded by the creator of the Walking Dead. It’s an interesting organization. They believe in IP experimentation, to the point that they’re working with a very non-traditional partner to do a non-traditional project. From what I can tell, they’re pulling in threads that a lot of us could only dream of accessing in a single franchise, such as streaming competitive gaming, or doing multi-title transmedia in a very real way.

To answer your question, this is what I think VCs should be spending more time in. How can I create something in entertainment that’s truly differentiated, and not just a pump and dump? I think a lot of people in entertainment feel very frequently that the interest level of some investors is around ginning up something on a new platform, getting a price tag on it as soon as possible, and selling it out before anyone overseeing it can figure out what it’s really worth. That’s not a great relationship. Whereas if they have a sincere long-term interest in being a member of a community and developing a property across 10 years or so, that’s an interesting conversation to be in.

That’s what I wish interested the investor class — creating partnerships like that and tentpoles like that, so the rest of us can look at it and think, “There’s an interesting place to think about, one corner of an ecosystem. Where can I think about my part in this ecosystem?” As opposed to what is all too frequently just an arbitrage play.

Rupp: I agree with that. There’s a big future ahead in IP creation, first on mobile and then going elsewhere.

Heatherly: I wholeheartedly agree with that. We have looked at, from an innovative perspective — we have some strong IP like Fast and Furious, Jurassic, Trolls, Minions. But we would like more. It’s amazing how little game IP there is out there that’s really extensible to other channels of exploitation, whether it’s consumer products or TV or elsewhere. A lot of game IP is really about that game, about the reason to engage with that mechanic. But I think there’s hope.

We were talking about Funko the other day. They do collectible toys. Video game-based characters are actually taking share in that business away from traditional entertainment. I think we’re at a point where we’ll start to see game IP turn into true Disney-like franchises. But having worked at Disney and having worked with game makers, the sensibility is very different. I think there’s a lot of value to be unlocked if you have more game developers pursuing game development from a standpoint of, “How can I use this to build a franchise?” In the same way Disney and Universal and Warner think about that when they make movies.

Above: The three pillars of the now-defunct Disney Infinity.

Chang: I did a decade of venture capital and private equity before I fell into games. When I started in VC, maybe 30 percent of the deals I saw looked good to me. As I got a bit older, maybe 10 percent. A bit older than that, one percent. That’s the right way to do it. As time goes on you start realizing just how difficult it is to grow businesses for the long term and make them sustainable. What looks good when you’re young and inexperienced doesn’t look so good after a period of time.

In gaming, what I’ve looked for has changed since I started coming to this conference in 2011. But where I’ve had the greatest success is when I spend time with people like yourselves, interesting entrepreneurs that believe in gaming, but the best ones make me feel emotionally and intellectually uncomfortable. When I talk to someone like, “You can make money doing this? You can get people to play games along these lines?” HQ Trivia was like that. “You can really do this?” Things that make you think, “God, you can get people to happily spend money on your game doing something like this?”

That’s always what I’m looking for: someone who makes me think outside of the normal boundaries. Again, it might make me somewhat uncomfortable, but at the same time, I realize that there’s a way to make money here with a differentiated product that no one has ever seen before. A different business model, a different game, a different play style.

From when we started in 2010 until now, I haven’t been surprised in a long time. In 2010 a lot of processes were new to us. They weren’t new in Asia, but it was pretty interesting to see what was going on with free-to-play mechanics here. I’ll never forget when Supercell launched Hay Day. I’m farming crops in Hay Day and I hold my hand out with my finger down. I’m sleeping on my crops. What a fun feeling. Or Angry Birds, when you did the pull-back on Angry Birds and flung the bird. It just fit. Have you had any of that one-touch magic in recent times? Have you seen something new on a mobile phone game that felt that different to you?

I’m always looking for something that makes me feel either physically or emotionally or intellectually uncomfortable, but it will turn out to be a really great idea down the road here. And no one has that yet today.

Above: Intel Studios

GamesBeat: Getting to the second part of that question, if the platform owners have their own interests and they want to push in a certain direction, push you guys in a certain direction, how much do you go along with it? Last week Intel announced Intel Studios. They’d love to see VR take off. They want to make it happen. They started a studio in Hollywood for immersive media. They want to team up with people and teach them how to use this technology to create new media. They cut a deal with Paramount as their first partner. What do you think of that kind of push, happening from a platform owner’s side?

Chang: Thinking of two companies where this has been somewhat successful, if not exactly — one is Valve and one is Epic. Epic has their engine. They made their own games and then they started licensing out their technology and other people started using Unreal. Valve had their own games, they had Steam, and then they brought in everyone else from the PC side to be on Steam. I don’t know that a platform like Intel can force us into something like that.

Bergel: There are at least two schools of thought, or two types of pitches that I receive in that context. One is, “Do the thing I say and I will give you a shiny.” That’s basically the relationship. The other is, “What do you actually need in order to make a better game?” How can I, as the platform holder, improve your life in some meaningful way? Clearly, as a game developer, you’d love to be exclusively involved in these kinds of conversations. Unfortunately, because it’s the way of the world, you’re frequently involved in the other kinds of conversations.

Those kinds of conversations don’t yield good product. They yield checkbox features and conversations that are very bounded. You incorporate something just as far as you have to in order to get the shiny. You’re dealing with game developers and they’re going to game the system, by definition. Whereas over here, if you can make a meaningful effort to understand what game developers in your ecosystem have challenges with, how you can make better franchises, how you can deal with people better in the longer term — what does it mean to develop their actual business, as opposed to just getting features?

Engaging in that conversation as a platform means you’ll find yourself on the receiving end of some really valuable information. There are a couple of platforms that do that. But at least these two schools of thought exist, and I have a definite preference for one over the other.

Heatherly: My least favorite thing are platforms who don’t give you the data. Part of being on a platform means I should get data. I have to say, Google is doing a fantastic job in the game space with developers. They’re helping us make better games, giving us best practices, and taking a very proactive approach.

We haven’t talked about Steam very much, but Steam is a very different marketplace than the mobile app stores. Part of it is because they’re run by game developers. That has become a vibrant marketplace that’s given birth to a lot of hits in the last several years, and not just Valve’s stuff. It’s stuff like PUBG that just comes out of nowhere to become one of the most played games in the world. The platforms that embrace gaming certainly build better, more lasting businesses than the ones who don’t.

Chang: You can’t force it. In 2011, at EA, I remember that Amazon was kicking off their platform, and then Windows as well. They used to be practically jokes among developers. We were only making our games ported over to Amazon Fire or Windows Phone because they were paying us — paying cost of engineering, or cost plus a little bit of money. Those things never really took off.

Rupp: Those things generally don’t tend to get prioritized. Fortunately I think the dynamics have changed with the platforms. It’s more balanced than they used to be.

Above: Mark Caldwell (CTO, left) and Brian Fargo (founder, right) of Robot Cache.

GamesBeat: I talked to Brian Fargo last week about his ICO. He’s raising money to create a token that can be used to buy digital games on the PC through an alternative app store to Steam. As Brian, I’m offering you guys 95 percent of the proceeds from digital game sales on my platform. I keep five percent. I also give consumers who buy these games the right to resell them. They get 25 percent of that sale price, which you guys set, and you get 70 percent coming back to you, the same amount you get now from Apple, Google, or Steam. Are you going to support me and put your games on my platform?

Chang: As much as it’s painful that Apple and Google and Xbox and PlayStation take 30 percent, there is something you get for that. Everyone has an opinion about whether they take too much.

Bergel: It’s really a user adoption question. How many people are coming through that store? Forget how it’s technically organized. From a business perspective that’s not the interesting part of it, blockchain or not. Will there be a mass of users engaging with this platform? I have a lot of love for Brian. He gave me my very first job in games. I would never bet against Brian necessarily. But a store, to somebody selling goods in it, is only as good as the number of people coming through the door.

If you’re Wal-Mart, I know you have a lot of customers. If you’re the corner store I know you don’t. Once it’s Wal-Mart everybody will go there because it has the customers. Whether it uses blockchain or not — I don’t care what cash register the corner store uses, unless it benefits me personally. Can I resell my games? That’s interesting, but is it going to be the thing that causes me to become a customer, and causes 10 million other people to become a customer? I don’t know yet. But when there are 10 million people, let me know, because that answers my question.

Rupp: I tend to agree with that. Not to mention, sometimes there’s risk in associating your IP with things that don’t work, that don’t get off the ground. I’m likely to wait.

Bergel: There’s also the cost of integration. How much effort is it to take a punt? If it’s easy, that’s not so much of a concern. But if you ask any of the developers here how many third-party APIs they’ve been offered to integrate which will only take an hour — [laughs] You have some sense of the issue. How many stores can you legitimately support before you’ve diluted your developer resources to the point where you’re no longer doing a good job at the one thing you said you could do?

It becomes a problem, especially in a live ops environment. If you have to replicate live ops teams, live ops events, technology, then you’re just going down into a fragmented morass of problems. What does it really mean to put a cryptocurrency-enabled thingamajig I’ve never heard of before with no reference case in my games? I don’t know. Do I want to be the first through the door? Maybe if I’m a real big crypto enthusiast, but I’m probably not that guy. Try the next guy and tell me about his experience.

Above: Rocket League continues to grow into an esport.

Heatherly: I feel like all the value in games going forward is going to be in games as a service. I’m less excited about ideas that revolve around premium games in general. Even if you look at the esports phenomenon, there’s a tension there. If you want to make your multiplayer game big enough, it has to have an accessible price point and reach enough people. I think there’s a reason these $30 games have taken off. Only a small number of $60 games can exist in the market.

If you look at Rocket League, one of the things that got them established and started building the esports around it was the fact that they were bundled in with the PlayStation subscription. Millions of people got the game for free and that jumpstarted the whole thing. I don’t want to say that free-to-play is the inevitability of the game market, because I don’t think that’s true. There’s certainly a viable market for premium games on Steam. But it doesn’t exist at all on mobile.

When people talk about cryptocurrency, it’s interesting. It’s hard for me to wrap my mind around — maybe this is where I’m getting old and set in my ways — but I came up through that Raph Koster mentality of, “the client is in the hands of the enemy.” Why would I want to give away control of my economy? That kind of thing.

GamesBeat: But you already gave that to Apple, Google, and Facebook.

Chang: It’s not a matter of “if you build it, they will come,” though. They have the users there.

Heatherly: Not only that. When people complain about the 30 percent scrape they give to those guys, I just think they’re being whiners. I used to work in the retail business, selling toys and stuff like that. Wal-Mart will take 50 points, easily. What Apple and those guys bring to the table is a level of featuring. They bring the device, the operating system. They have everyone’s credit card, so it’s all frictionless. I’ll happy pay. When I ran Club Penguin, I can’t tell you what a pain it was to run a payment system. It was a major distraction from the game. You can have your 30 points to take care of that.

Rupp: I’d like to just triple down on this point, because I was in free-to-play back before we ever heard of app stores. Life is so much better now. We rolled our own banking system. We included credit cards and Paypal and prepaid cards and pay by mobile, across so many countries. The fraud, oh my God. Different fraud resolution methodologies — including aggregators, we probably had several hundred payment mechanisms across all the territories in the world. Then we had to advertise on top of that in order to bring customers in.

We were spending way more margin than we currently pay Apple and Google. If you remember the bad old days of being on the open Internet and trying to run a banking system and pay for advertising in a fragmented ad ecosystem, the world of Apple and Google and Facebook—yes, it sucks, but it’s so much better than what we used to have. Is it improved or supplanted by this new thing? I don’t know. Maybe. But what we have now is better than people give it credit for.

Chang: The gaming markets have never been larger for any of us.

Above: The App Store

Rupp: Right, because of these innovations and because of the centralization of these services.

Heatherly: And it’s growing faster than any other form of media. I’d rather be in this business than in television. As I look at my colleagues who work in cable TV….

Chang: Looking at you guys right now, there’s a reason why consolidation is happening with things like Fox. They’re being chased by companies like Fox and Amazon.

GamesBeat: If I’m Brian Fargo I’m saying you’re happy to be slaves to the app stores. [laughter]

Bergel: Yes? I mean, you’re talking to people who have extremely large businesses. They haven’t been unkind to us. Maybe his first customers are not us. They’re people who are more experimental, more interested in trying something new because they’re starting from a dead stop. That’s fine. There’s nothing can be right. Both sides can be right in this ecosystem. But to come to someone who has an established business and say, “No, you’re doing it wrong,” well, I have a billion dollars that says you might not be right. Go start something, prove it out, and we’ll see.

Disclosure: The organizers of Casual Connect paid my way to Anaheim, California. Our coverage remains objective.