Soon after Andrew Reinhard started his Archaeogaming website in 2013, he got a chance to practice video game archaeology in the real world. He led the famous Fuel Entertainment excavation, heading up the team that dug up old Atari video game cartridges out of the New Mexican desert. Afterward, an old copy of the Atari 2600 game E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial found a home at the Smithsonian — because, like all artifacts, it belongs in a museum.

But Reinhard doesn’t like distinguishing between the so-called “real world” and the “virtual world.” Most of his work takes place in video game spaces, exploring titles like Hello Games’ No Man’s Sky or Bethesda’s The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. And finding artifacts in these worlds is just as real as unearthing a dusty cartridge.

“I hate this real and virtual distinction. I like to call it a difference between natural and synthetic. Both are real,” said Reinhard in a phone call with GamesBeat. “We always have our heads in our phones and our screens. That’s as real an interaction as any other kind of interfacing with other people and other kinds of entertainment. I don’t know. I just thought these places are very archaeological to understand. People make these things. People live in them. What does that mean as an archaeologist?”

Reinhard’s love for achaeology and passion for games first coalesced when he modded Skyrim with a Latin language quest as an experiment to see how games could be used to teach languages. Then he moved on to start a guild in Blizzard’s World of Warcraft for fellow Latin-lovers, called Carpe Praedam (“‘Seize the booty” in Latin, or ‘seize the loot,'” explained Reinhard with a laugh). The more he played, the more he began to notice the architecture around him. It’s something that he’s written a whole book about — Archaeogaming: An Introduction to Archaeology in and of Video Games — which will be out this summer.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

“All these games have so much lore,” said Reinhard. “It sounds naïve to say now, but 10 years ago, eight years ago, it was like, hey, this is archaeological. Over the past six-to-eight years my thinking had gotten beyond — ‘Let’s look at how archaeology is portrayed in a game. If a game has an ancient temple, what’s that about?’ – to treating video games as archaeological landscape sites and artifacts.”

Every game is different, and he doesn’t discriminate between what kinds of games he studies. He dove into Skyrim VR to investigate the ways it interprets Norse mythology in its own fantasy world. His daughter got him to try Epic Games’ Fortnite: Battle Royale recently, which sparked a train of thought about the way people learn about locations and how to traverse them. And he’s studying Will Crowther’s 1976 text adventure Colossal Cave Adventure as part of his PhD at The University of York.

“It’s a text-based adventure from the 1970s that, over the past 30 years, because the game was written and released as open source — people have kept modifying the code and making the game bigger. I’m really curious to see how that game evolved,” said Reinhard. “To me, that’s an archaeological way of looking at stuff. It doesn’t need to have images at all. It can just be words. But if it’s a game, there’s certainly archaeology in it, no matter what.”

The tools of the trade

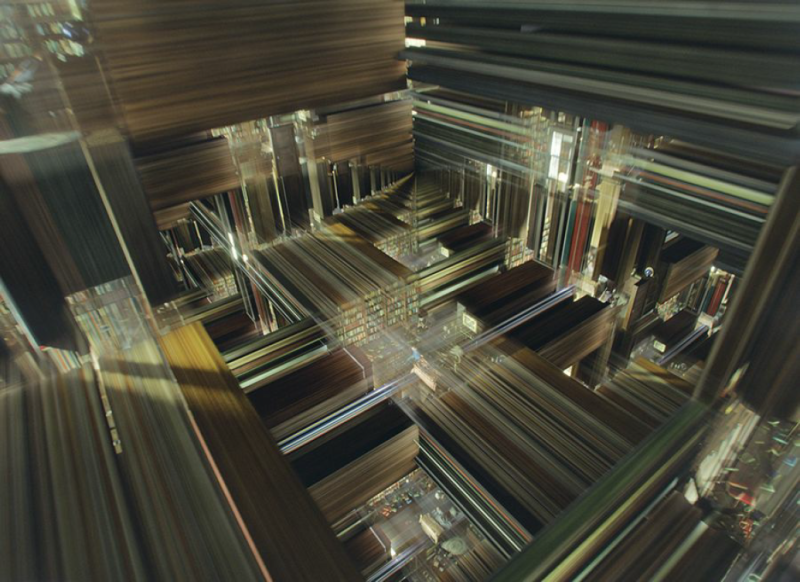

Above: Andrew Reinhard’s base of operations while on an archaeological survey in No Man’s Sky.

Reinhard’s Ph.D is on “developing archaeological methods and tools that are unique to doing the archaeology of synthetic worlds.”

“I call these things digital-built environments,” he said. “I’m trying to figure out what I can take from a traditional archaeologist’s tool kit, as far as the questions that are being asked, the data being collected, and applying that to a digital space and seeing what sticks.”

Part of his studies is “code paleography,” which is a really cool term that rolls off the tongue and sounds like something from a Neal Stephenson novel. Traditional paleography is the study of ancient writing systems. Reinhard is applying that to code and seeing how it’s written and how it evolves.

“Paleography and epigraphy have been used for decades, if not centuries, in understanding inscriptions,” said Reinhard. “People write on stones, inscribe monuments with text, or leave handwritten papyrus and stuff like that. So what’s our modern papyrus? It’s code. All this stuff is based in code. You have versions coming out, different people doing different parts of the same project.”

The online repository Github is a great resource, because it keeps track of all the versions of a game that someone has uploaded. Often, it’s accompanied by patch notes to explain the differences between each one.

In addition to digging into the code itself, Reinhard also uses whatever tools he can to take pictures and video footage of a site that he’s examining. He’ll also pull 3D meshes and make 3D models of a landscape. Sometimes he constructs 360-degree views of a location using static images.

“Or if I’m parachuting in, I can get that top-down view, and then land and walk around something,” said Reinhard. “What that can do is, there are open source, open access online tools that allow you to convert that video into a series of hundreds of frames, still images, that can then be used to compile a 3D model that you can rotate on a turntable. You can extract a 3D image from that, or extract something you can 3D print from that.”

The Prime Directive of archaeogaming

Above: Andrew Reinhard inspecting “permanent ephemera” in Fortnite: Battle Royale.

But most video games aren’t just empty spaces. Characters live in these worlds, so how should a video game archaeologist interact with the locals, so to speak?

For his first archaeological survey of No Man’s Sky, Reinhard assembled a team of 30 people. Before they went in, they came up with a “Prime Directive” for how to treat nonplayable characters.

“What happens when we meet an AI in a virtual space? As an archaeologist you want to be as neutral as possible, because otherwise you really have this interaction that affects how the game behaves and how you’re treated and how you treat AIs and NPCs in the game,” Reinhard explained. “We made this in the event that we would across AIs that are hostile or neutral and otherwise, and what to do when we interact with them.”

As an example, Reinhard says that they’re “big fans of dying.” Rather than engage with an NPC and possibly changing the world, they’ll let it kill them and then simply respawn. Or, if the game features permadeath and they can’t reload from a previous save, they’ll do their best to avoid that particular area.

The Prime Directive also dictates how they interact with artifacts that they find. Reinhard says that they try to follow standard archaeological ethical guidelines. They’ll document the object and take pictures, but they won’t remove it and place it in their inventory. And they certainly wouldn’t sell it. However, this gets a little trickier in a game.

“Sometimes looting is allowed in games. Sometimes looting is encouraged in games. Sometimes you can’t proceed through a story in a game unless you loot something, take something, destroy something that’s of cultural importance to the cultures in the game,” said Reinhard. “For some folks that’s a non-starter. No, we can’t do this. And for others, if it’s part of the game mechanic and part of that world’s ethical setup, then maybe that is okay. In games you’re dealing with invented physics, invented technologies, invented cultures, all of that stuff, but you’re also dealing with invented ethics, too, that may or may not be parallel to the ethics we have as people.”

Artifacts of video games

In the natural world, archaeologists might collect stone tablets detailing customer complaints from ancient Babylon, but in the synthetic world, one particular type of artifact tends to crop up: glitches. These are unique to digital spaces, though they’re not the only type of artifact to collect and study.

“You find a glitch, that glitch gets patched, and you never see it again,” said Reinhard. “It’s locked in a space and a time, just like when you find a human skeleton, and that skeleton is interred in such a place below the earth or whatever, and then it gets removed for documentation and ultimately hopefully repatriation. And it’s gone. All you have left is the data you collected, the photo you took, the scientific samples you extracted. With glitches it’s very much the same thing.”

Reinhard muses on coming up with a “glitch typology or typography,” a way to categorize all the different kinds that occur. Some come from “counter-play,” for instance, where players are actively trying to break the game. Others are purely accidental, because games are so complex and enormous that it’s near-impossible to catch everything.

“Going back to Skyrim again, and also Assassin’s Creed, some of the earlier titles—you’d play the game and there were people without heads walking around, or their faces were all screwed up, or mammoths were falling from the sky for no reason,” said Reinhard. “I’ve seen that. Man, this is awesome. Other people are really frustrated and I’m like, no, no, this is the coolest part of the game!”

Reinhard describes the peculiar effect one particular update had on No Man’s Sky. In August, Hello Games released Atlas Rises, which introduced features like new storylines and types of planets. Reinhard documented some interesting results in the aftermath.

“People had built their bases or left comm stations around. When the landscapes change, sometimes those bases were floating up in the air,” said Reinhard. “That was kind of weird to see, a very surprising thing for me to come across. Wow, this used to be a mountain, and now it’s a desert, and this thing is 100 meters up in the air. Or to have to dig 100 meters down to get to comm stations people had left in the previous version of the planet, that was wild.”

Now more than ever, people are documenting the unique experiences they have with games. Before, these events and interactions vanished into the ether. They had no permanent effect on the landscape of the game and they left no evidence to suggest they ever happened. But through videos like on YouTube or on livestreaming platforms like Twitch, folks can peek into the past or watch as things unfold.

“That becomes part of what we call intangible heritage. UNESCO defines intangible heritage as things that are part of a culture that don’t leave any material evidence behind,” said Reinhard. “You can think of dances by various Native American peoples, for example, where there’s a set way of doing a dance and that’s part of their heritage that’s communicated over time. That in itself is archaeology. But it doesn’t leave a trace afterwards. These kinds of events, unless people record them and put them on YouTube, it’s the same thing. It’s intangible heritage. It happens once and it’s gone. That’s a kind of artifact as well.”

In recent years, celebrated narrative games like Firewatch and Gone Home have emerged. These tell compelling stories, but archaeology reveals another kind of story: one that’s all about the players, the decisions they make, and the impact they have on the virtual but very real worlds they inhabit.

IndieBeat is GamesBeat reporter Stephanie Chan’s weekly column on in-progress indie projects. If you’d like to pitch a project or just say hi, you can reach her at stephanie@venturebeat.com.