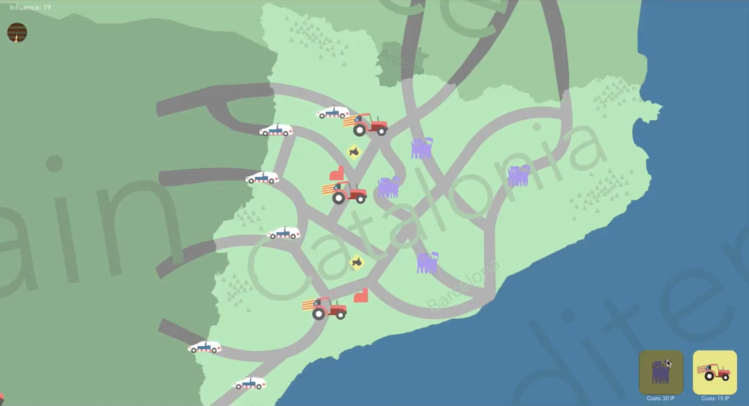

Las Tractoradas is a tower defense game with a political influence: the ongoing crisis in Catalonia. And it stars what’s become a populist symbol of the Catalan Independence Movement: tractors. A group of six high school students participating in the NuVu Studio program created the game in only 11 weeks. Though it isn’t available yet for download, a video of in-game footage and a design document is available online.

“The entire game was based on the news,” said Amanda Brown, Las Tractoradas’s project manager. “It takes place on a map of Catalonia, and the cars and tractors specifically come from certain areas to feel truthful to real life. The tractors block the police cars because in real life, that is what the Catalan citizens did in order to vote and protest against Spanish rule.”

The goal is to block off the local police force using tractors so that voters can make it to the polls. In real life, Catalans clashed with officers over a referendum around whether or not Catalonia should leave Spain and become an independent country. As research for the game, Brown and her teammates, game designer Joshua Shapiro and programmer James Brink, interviewed people in Catalonia to learn more about the events.

NuVu coach Seth Alter presented the students with the topic of Catalan independence. The program assigns mentors to each group, and they guide them through the development process. NuVu is a paid program for middle and high school students that focuses on interdisciplinary projects that can involve technology such as augmented reality or artificial intelligence. It’s split into studios, which run for two weeks and focus on one problem, 11-week terms for longer projects, and year-long programs where students do a deep dive into learning a discipline or work on multiple projects.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Here is an edited transcript of our interview.

GamesBeat: Can you tell me a little more about yourselves and how you got into game development?

Amanda Brown: I have always been interested in video games, and more importantly, the story and inspiration for the game. I never thought that I would be able to create a game, as I always thought I would just be a player. When I was presented this opportunity, I knew I had to take it. Not only have I always wanted to create a game, but I am also into politics and current topics. I already knew about Catalonia, but a number of my friends and family didn’t, so this game was a way for me to inform them about Catalonia and what is happening.

Joshua Shapiro: I grew up in Needham, Massachusetts, and I go to Beaver Country Day School. I had never done any work creating games before I went to NuVu. I was put into a studio where we had to design a tabletop game and because of my game design, I was chosen to be the game designer for the Catalan Game Studio.

James Brink: My name is James Brink. I am currently a junior at Beaver Country Day School. When I was younger, I really liked to play video games, and I wanted to learn how to make them. I taught myself programming. I’ve dabbled in some game modding, but Unity is the first professional game engine that I have used.

GamesBeat: What was it like to talk to people in Catalonia? How did that inform your game design decisions?

Brown: It was an amazing experience, the person we talked to was nice and informative. He knew what the tractors symbolized and was able to share stories. The tractors in the movement have not been significantly publicized in North America and the United Kingdom, so people do not understand the importance of the tractors and how they are used to block police officers. So by talking to people in Catalonia, we were able to fully understand why the tractors were being used.

We originally had the tractors coming from the Spanish border, so it looked as if the tractors were coming from the neighboring countries instead of the rural parts of Catalonia. We were able to fix that error and were able to obtain their insight on our artwork and how it could be improved.

Brink: It was really intriguing to hear the juxtaposition of what was on the news and what was actually happening. Some things were over exaggerated while others such the firefighters protecting the protesters were not even mentioned in all of the news outlets. There were minor details such as where the police spawned — they now spawn in Catalonia — that changed after we had our interview.

GamesBeat: What were the main challenges in developing the game?

Brown: We had three main challenges in developing the game: First, we were all new to game coding. We had all performed coding before, but we had to pick up the game developing software we were working with.

Second, there was news in the United States about Catalonia, but not necessarily the insight of what was actually taking place. Luckily, we were able to take information from news reporters who were present in Catalonia along with citizens from Catalonia some of the team members knew.

And third, the time frame was challenging. We spent two weeks on the basic mechanics, art, and planning of the game. Then, two weeks later we added more features to make the gameplay harder and more interesting. But due to the time frame, we were always working against tight deadlines and sometimes frightened that we would not finish.

Shapiro: The main challenges in developing the game were actually combining all of the components of the game and making it run smoothly. Once we decided on how the game would run, we had to actually make the game, and then do a lot of play testing in order to find bugs and find parts of the game that we didn’t like.

Brink: From a programming perspective, making the game manager was quite challenging as I had refresh on how classes work in C#. Something that was challenging was using Git. Git is a software used so that people can collaborate on code. It had a steep learning curve, and we almost lost our progress a couple of times. When Josh and I decided to refine our game in open innovation, it was quite difficult to make the game more fun. We had to spend a lot of time thinking, planning, and testing to make sure the game is as enjoyable as possible.

GamesBeat: Can you tell me more about the game? Is there a story, and if so, is it based mainly on the news or is there fiction as well?

Brown: The game takes place on Catalonia’s polling day. Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, and Catalonia recently voted to separate from Spain and form their own country. Spain wants Catalonia to stay within Spain and police officers became violent with the voters to restrain and prevent them from voting. In the game, police cars from Spain and within Catalonia try to go to the polling station to stop the vote from taking place. To block the cars from going to the polling station, the player needs to send a tractor from a farm.

The entire game was based on the news. It takes place on a map of Catalonia and the cars and tractors specifically come from certain areas to feel truthful to real life. The tractors block the police cars because in real life, that is what the Catalan citizens did in order to vote and protest against Spanish rule. The tractors ended up becoming a symbol of resistance which was the inspiration for the game. Before we knew what we wanted to make of the game, we knew that we wanted the focus to be the tractors.

Shapiro: The main point of the game is to send protesters to polling stations in order for them to vote. Once they vote you get points. As you are trying to send the protesters, the police come from the border of Catalonia to try and stop you. You need to try to be faster than the police, but, once you have enough points, you can purchase tractors to block the road and protect the protestors. There are 8 waves of police, and once you make it through all 8 waves, you win the game. Alternatively, you lose if the police destroy polling stations and that causes you to go into negative amounts of points.

GamesBeat: Why did you decide to create a game about the Catalan protests? Has your perspective about games or the Catalan Independence movement changed after developing the game?

Brown: One of the teachers at NuVu came up to me and asked if I would be interested in creating a video game. At my school, I am head of the Board and Card Games Club and I’m an active video gamer, so he assumed I would be interested. He asked me if I knew anything about the Catalan protests and we engaged in a long conversation about what was going on and what we thought. Then, he told me about the tractors and I was instantly intrigued.

I did most of the research for the project and kept everyone up to date. I love reading and learning about current events and the combination of current events and video games seemed like a good fit for me. After talking to people from Catalonia, my whole perspective on the situation changed. For most Americans, it’s difficult to look at something across the globe and think it is actually taking place. I had never met anyone that has lived in Catalonia. From my research and conversations I learned so much information about the people of Catalonia and why they use tractors as a symbol. I think people’s perspective of the situation would be more informed after meeting someone from Catalonia.

Brink: Once we started to do research, we took note about the tractor blockades which lead to a tower defense game. After spending a solid 5 weeks on developing a game that I would make changes to, I’d say that I really appreciate how much work and effort goes into making a game. It’s weird playing games now because sometimes I just ponder about how the game works instead of playing the game.

IndieBeat is GamesBeat reporter Stephanie Chan’s new weekly column on in-progress indie projects. If you’d like to pitch a project or just say hi, you can reach her at stephanie@venturebeat.com.