It’s been over five years since developer Mike Bithell launched Thomas Was Alone, which sold over a million copies and won a British Academy Games Award. In the years since, he’s started his own studio, Bithell Games, published author Mike Futter’s The GameDev Business Handbook, and released a number of stylish, narrative-driven experiences such as the hard-boiled robot detective game Subsurface Circular.

Even though most people associate him with sharp writing, Bithell’s background is in game design. Thomas Was Alone was the first thing he ever wrote.

“Thomas Was Alone is far from perfect, story-wise, but I think I hit enough of it that it sort of worked. I got away with it,” said Bithell. “And then I just finished that, and I feel like I’m pretending to be a writer ever since.”

Before 2017 draws to a close, I chatted with Bithell about how he’s evolved as a writer, how he thinks indie games have changed and what’s up ahead, and whether or not “emotional resonance” is something that still needs to be solved in games.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Here is an edited transcript of our interview.

GamesBeat: You mentioned that you hadn’t written anything before Thomas Was Alone. Is that right?

Mike Bithell: Yeah, nothing fictional. I’d written a lot of design documents and these massive sprawling 200 pages about how this third-person shooter is slightly different to all other third-person shooters. That kind of thing. But I’d never written any fiction, never written any kind of stories. Not since primary school.

Thomas Was Alone didn’t have any money, so I couldn’t afford a writer, but I knew it had to have a story. So I just kind of wrote one. I bought some of those awful books you see in bookshops, how to write your first screenplay, how to — they’ve always got weird titles, like how to become a great writer in 24 hours, that kind of thing. I bought a bunch of those hack books and tried to glean what I could, and then I just went for it. I got lucky. Thomas Was Alone is far from perfect, story-wise, but I think I hit enough of it that it sort of worked. I got away with it. And then I just finished that and I feel like I’m pretending to be a writer ever since.

GamesBeat: That’s interesting, because I definitely associate you with strong narrative games, and especially with Subsurface Circular, which is very interactive fiction. How have you evolved as a writer since those first days? How do you view narrative design and game writing at this point?

Bithell: I guess in terms of my evolution as a writer, it sounds really weird — I only just added writer to my Twitter profile like six months ago. It felt like this amazing moment. I’m going to admit to this. In terms of my progression as a writer, I think the main thing for me has just been gaining confidence and also just accepting that’s what people like about my stuff.

I came from a design background. I was a designer first, for many years on other games. I was always seeing myself more as a designer who put story into my games, because it had to have story. Especially Subsurface Circular, it was very much about realizing, no, most people who like my stuff like it because of the story, so let’s accept that. [laughs] Make something that really just focuses on the writing.

I mean, there is obviously game design in Subsurface Circular, but as you say, it’s more that interactive fiction thing of getting out of the way of the writing a bit with the game design. It’s funny how many of my friends called me or messaged me and said, you’re finally making the game about the thing you’re good at. Which was — I get distracted by other stuff, I do. It felt like a good mesh with my skills. It seems, from the audience reaction, that that’s what people want me to be doing, so I’ll probably do some more of that and see how it goes.

More generally, my big thing with game writing is always just — it’s not — it’s really rare that a game is badly written because the writer is bad. I think it’s a real problem across the industry, when some can’t tell a story consistently, usually because of the methodology of making it. I know when I was working in bigger studios, you’d be making the game, and the writer was someone who they’d remember about six months before shipping the game, “Oh, we need a story, we need to write something.” You’d bring in a writer, have them do stuff, and then it would get tweaked. You’d have to remove a level that was a big turning point for a character, or the marketing company would say that the snow level was just so beautiful it had to be in the trailers, but it was like 80 percent through the game, so you had to put that level earlier in the game, and then that messed up the story.

So often with game stories, the reason the story doesn’t land is because of that. It feels like cheating as an indie, because obviously I get to decide what happens. I get to make the choices in the game development to support the story that I’ve written. It’s a very egotistical kind of thing. I can protect my work in a way that my friends who work in writing for big triple-A games — they’re not important enough to the process.

It’s really telling when you think about which big studios make great story games. They usually are the ones where the writers have power, the ones where the big name is the writer. The studio’s owned by writers. It’s such a weird, specific job that both people underestimate its importance, and also lots of people — this is true of design as well. Lots of people feel like they can write, even though they can’t. They change things around. I see that frustration from others. Indies, we get away with maybe being not quite as good at writing, but at least our stuff is consistent and delivered well, because there’s no one meddling with it. That’s a freebie we get as indies, which makes us look better than perhaps we are.

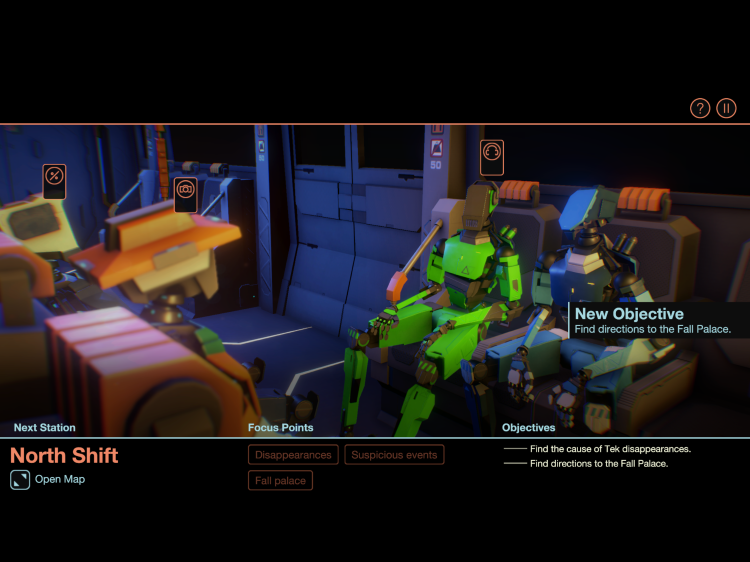

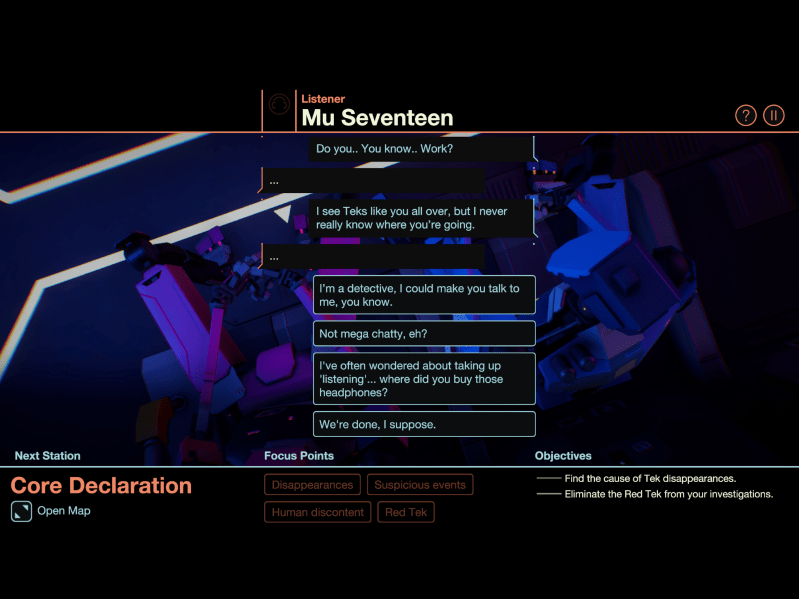

Above: A scene from Subsurface Circular.

GamesBeat: You mentioned that before you saw yourself as a designer first. Do you see yourself reaching for the writing toolkit first to express yourself now, or explore ideas in games? Or is it an organic process?

Bithell: It’s an organic thing. It all grows together. I don’t necessarily think of games as any more of, “Oh, this is an idea, I want to make a game of it.” It’s more like, how I want to stretch myself or what I want to learn, and also what my team is good at, who’s around. With Subsurface, a big part of the reason that game exists is that a friend of mine, Moo Yu, who’s a really great coder, had a bit of free time. He had a spare moment in his schedule, and we went for lunch and we were talking about how he was thinking maybe he should do a little side project. I said, well, this is the chance for us to work together.

Subsurface happened because I wanted to write more stories and this guy was available for a few months. Some of the stuff we’re doing now is happening because my designer/coder Nick Tringali had some spare time, and me and him started chatting about an idea. That evolved and became its own thing internally. They come up organically, but yes, in terms of me with it, I tend to be thinking about the design and the writing kind of simultaneously.

But generally I think you can get further with a good design and no idea of a story than you can with a good idea for a story and no design. Mechanically, we’re making interactions. If there’s no idea for an interaction then the story often just bounces around my head. There are stories and worlds I want to do things with, but I don’t have an idea of how they play yet, so those are on the back burner. You need both, or at least I need both to kick something off.

GamesBeat: You mentioned that in the past we’ve seen triple-A publishers and developers have undervalued writers. Do you think that’s changing? It seems like we’re starting to see a lot of strong cinematic narrative games. Or maybe it’s that they’re getting more of a spotlight this year.

Bithell: I think it’s making more sense. I think a big part of it is that the audience have demonstrated that they care. I remember five years ago — well, probably more than five years ago — but it wasn’t really demonstrated outside of a few outliers that players really wanted great stories. I think one thing that the explosion in indie has caused is big studios notice. They notice that players care about — in Thomas’s case, literally they care about rectangles. If you put story in, that appeals to an audience. That’s become a focus.

It’s interesting talking to triple-A folks now, the amount of thought that’s going into things. Like [Horizon: Zero Dawn] for example, the amount of time and energy that went into that world-building. But behind the scenes, just how much iteration happened in terms of who the main character is, why the world’s the way it is — I’d swear those conversations didn’t happen at that scale even five years ago. It feels like people are realizing the importance of embedding this really strong narrative and world into your game.

A part of it, as well, is commercial, in terms of — we can’t underestimate the impact the Marvel movies have had. Everything now is thought of as this, “Can we do an extended universe? Can we branch this out?” I’m sure part of the reason something like Horizon has so much energy put into its inception is that the people who are paying for it say, “Well, we want to be able to make five movies and three spinoff games” and all this kind of thing. Story is crucial to that. And as we enter this period where big budget stuff is trying to build franchises and serialize, story matters again. It’s not about making a cool trailer anymore. It’s about making characters and worlds that people want to keep going back to and exploring. Story is a relatively cheap way of achieving that. I think there’s more respect there.

I also just think a big part of it is that the audience is aging and requiring more advanced storytelling. I think the people who care about story are finding themselves in more senior roles in a lot of these studios. It’s a great time for story in games. I think we’re not quite at the golden age. It’s not as if everyone wants the video game equivalent of — oh god, Orson Welles, dammit, it’s such a cliché — Citizen Kane. But it feels like we’re nearly at the Sopranos of games, hitting those kinds of stories that really resonate and matter long term. That’s interesting.

GamesBeat: Do you think that’s where we’re going to go next year? See even more robust storytelling, maybe in VR? I know a lot of VR developers I talk to are trying to figure out how to make emotionally resonant experiences. Do you think that’s the next step?

Bithell: There’s a rant I could go on. I may go on the rant. Let’s do the rant. This isn’t targeted at any particular person, and definitely not VR people. VR is interesting, because there’s such a new requirement of technology. But I’m so bored of emotional resonance being a thing. We’re dreaming of a future where we can make a player — like, “I cried at five games last year.” I don’t think that’s rare. I think everything emotionally resonates.

I see a lot of — it feels like we’ve been having the kind of, “When will a game be made that can really connect with someone on an emotional level” conversation for 20 years. And there’s definitely — we’ve done it. It’s been done. Emotional resonance isn’t, to me, a massive objective. I don’t strive to make someone cry. That’s not an objective I have, because to be honest, if you’re telling stories about characters, that’s not a technical hurdle. There are people — these stories resonate. We’ve done that.

For me, it’s more about what we’re trying to say and how we say it and telling satisfying stories, but also trying to have an opinion, trying to have a statement to make with what we do. Emotional resonance, it resonates with me personally. [laughs] It feels tired. I see a lot of prominent game story people still talking about it as if it’s something that hasn’t happened yet. I feel like a lot of the people who talk about it have already achieved it, so move on.

Let’s have something to say. Let’s create work that talks about — it doesn’t have to be political. It can be something that talks about the human condition. Let’s not make a game that can make you cry. Let’s make a game that can make you feel lonely. Or I shouldn’t use “lonely” because I made Thomas Was Alone. That’s too self-referential. But can we make a game that stimulates the feeling of being an outsider? Can we make a game that makes you hate someone? There’s much more depth we can achieve in games and much more we can talk about and discuss and do than, “Can we make someone cry because their horse died?” Or their dog died, or some animal that they were in any way emotionally attached to died. We’ve done that. That’s fine. That’s a solved problem.

Anyway, that’s my rant over. I apologize. With the VR thing, there definitely are really interesting unknowns in terms of how you tell stories in those, because you have a player perspective that’s completely controlled by the player. The player’s position in the world as well. The funniest experience — a couple of years ago, I played [The London Heist for PlayStation VR]. There’s a scene in that where this angry bald guy is towering over you and yelling abuse at you, and it’s meant to be very intimidating. But I’m quite a tall man. I’m about six-three or six-four. I’m taller than him, so he was kind of a small man yelling aggressively at my chest. It was hilarious. It was funny and not intimidating at all.

It was one of those moments where you realize how much of story is tied to something as daft as how tall I am versus how tall the person shouting at me is. There’s lots of things like that with VR that are interesting in terms of how you tell stories. It’s not an area I’m doing any work in, but I’m intrigued to see what the solutions are to those problems. So yeah, I’m excited by that. I’m excited by just generally smarter stories being told and us striving for a bit more than just, “Can we make someone cry?”

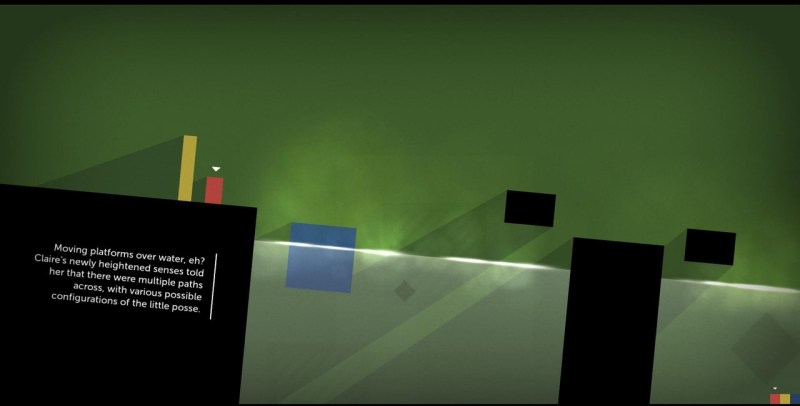

Above: Thomas Was Alone is a game about loneliness and rectangles.

GamesBeat: Do you have any thoughts about how indie games have changed in the last decade? Or is that too long a time frame? Maybe the last year? Do you think we’ve seen any trends, or have you personally noticed any changes happening there?

Bithell: I think it continues to broaden, which is really exciting. It feels like — I mean, obviously there’s more people making and shipping games. That’s something everyone talks about. But on the whole that’s incredibly positive, that every year it feels like there’s less and less gatekeeping, less and less other requirements to get into the club. That’s cool. It feels like more and more voices are being heard. It feels like there’s more diversity in what’s being made, which is just really cool. And it’s something that — I just selfishly like that, because it leads to more interesting stuff happening. That’s a big trend.

When you look at 2012, say, when Thomas came out, those of us who were making those games, we were very much painted as these kind of artists bucking the system, but if you looked at any of our CVs, we’d all worked at big studios. We all had that kind of industry history. Except [Rami Ismail]. He’s the one outlier who always ruins any statement I make about indies. But the bulk of us, we’d come up through traditional industry stuff. That’s fine. I don’t want to knock myself or anyone else. But that was a very close club.

As the tools get more and more straightforward, it means there’s more and more opportunity for people to make interesting stuff, and for that stuff to be different. I see backlash to that. But for me, I always go back to Microsoft Word. Microsoft Word doesn’t make you Stephen King. I don’t know, he strikes me as someone who might be really against using a desktop — but anyway. The accessibility of the tools doesn’t make people good writers, but it means more and more people can use writing tools to write, I guess is my point. It benefits us all that more and more people are able to make a game.

Not all of those games are going to be good. Most of them will suck. But they’ve always sucked. Now it’s just there are more of them and a more diverse range of people making them. That’s cool. The cycle continues beyond that in terms of things like console support. We’re very much with the Switch. We’re very close to what happened with the Vita in terms of indie games, where Nintendo needed software for their platform and triple-A, big publishers were kind of like, “I’m not completely convinced the Switch is going to take off.” So Nintendo has reached out to indies and has this amazing swell of awesome indie talent making cool stuff. But then that will cycle back as a new platform will become the new poster child platform. The Vita definitely had that period where it was for everything, and then not. PS4 as well had a massive indie swing at the start. So we’ll see that cycle continue around a few places, which is fine. It offers great opportunities for people to make stuff.

Beyond that — that’s it really? And broadening of genre. We’re seeing more and more different kinds of games. What’s interesting about that for me right now is I worry we’re about to enter a period where we focus back into genres. It feels like everyone I talk to is thinking about doing a PUBG style game, and that worries me. I was around for World of Warcraft. I remember what happened when everyone said, “Wow, that’s massively successful, let’s make our own version.” I’m a little bit concerned about that, that people focus too much in “these genres are doing well so let’s buckle down.” But yeah, it feels like an exciting time to be making games and playing games. There’s lots of different stuff. Every niche is catered to.

GamesBeat: Can you talk about, moving forward, what you think we’ll see in 2018, or what you’re excited about seeing? Is there anything you’re looking forward to that you think is really cool, whether it’s a game or a trend or anything else?

Bithell: I’m really excited — I’m keen to see — it feels like indie is at a turning point where certain technically challenging things are getting much easier. One, for me, is online multiplayer. That’s definitely something that feels like it’s getting really accessible to smaller-budget projects. I’m interested, just from a design point of view, what that’s going to lead to. Are we going to see an indie MMO, a great indie shooter, a great indie genre that we don’t even know? We’ve obviously seen those before. We’ve seen multiplayer happen. But it feels like that’s about to get democratized massively. I think that’s going to lead to some really interesting stuff next year, hopefully.

Beyond that, trend-wise, it is interesting seeing people working in different ways. Especially in the U.K. The financial situation in the U.K. in particular is pretty unpleasant right now because of all the Brexit stuff, but you’re seeing more and more remote working situations. People not doing the office thing. I’m interested to see how that affects the stuff that’s coming out. We’re going to see some games made by international indie teams, or weird mishmashes of people collaborating. You’re already seeing a number of people in the indie space who are working on several projects with different teams. That’s interesting to me, that we might see faster cross-pollination and some interesting stuff out of that.

Those are the two things I’m most interested in seeing the outcome of. And then of course we have a hardware generation coming up a couple of years from now. As a designer that’s going to be interesting, see if that opens up any avenues for us. I guess as well, the one last thing is I want to see if other people do the shorts, if other people go and make smaller games. It’s worked out well for us, and I’m interested to see what other developers do with that model, or if they even care. Hellblade is a much bigger example of this, but games finding different sizes that work for the audience is something I’d like to see more if. I’d like to see us move away from, it’s either $60 or $20 or free-to-play, and find some different scales and price points that work.

IndieBeat is GamesBeat reporter Stephanie Chan’s new weekly column on in-progress indie projects. If you’d like to pitch a project or just say hi, you can reach her at stephanie@venturebeat.com.