A couple of games have experimented with creating museum spaces: Cardboard Computer’s Limits & Demonstrations is a miniature gallery set in the Southern gothic universe of the point-and-click adventure Kentucky Route Zero. Tom Kitchen’s Emporium is a moody study of grief, featuring everyday artifacts put on display like found objects. The Milk Gallery is a virtual gallery that operated as an “alternative art space” and featured new exhibits every month.

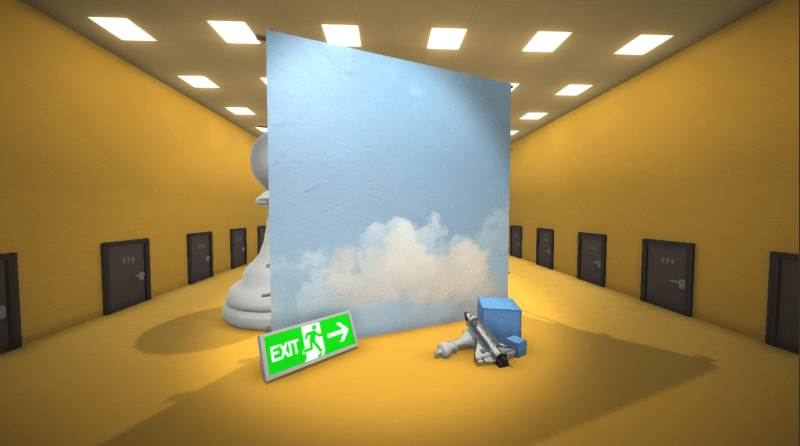

Pillow Castle Games‘ Museum of Simulation Technology adds its reality-bending exhibits to the list. Its puzzles revolve around forced perspective. In one sequence, you find a tiny door. Moving toward it literally makes it bigger, and then you can pick it up and slot it into the wall and stroll through as usual. It’s a simple concept, but it simmers with surreal intrigue. It feels like the museum exists in a dream, one where everyday objects now have a bizarre utility that wouldn’t exist in waking life.

“This game is less about logical puzzles and more about how weird things are,” said Albert Shih, the founder of Pillow Castle. “A kind of personal goal I have is to show that even with all the video games that have been created so far, there’s still more space for video games to feel surprising and magical and new.”

Shih has been working on the game for a while, and he debuted a demo back in 2013. It was a solo project at first, but now he has some teammates he can lean on. The game is still somewhat nebulous, which is why Pillow Castle has decided to forego any kind of crowdfunding campaign for now.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

GamesBeat: What’s your background, and why you did you make Museum of Simulation Technology?

Albert Shih: I have a very unsubstantial background. MoST started out as a super short programming project in college that I further developed during grad school. Afterwards, I worked on and off while taking part-time programming jobs to see if I could make this project into a full-time pursuit. Eventually I did!

I knew I wanted to work in video games but I never really consciously decided to be an indie developer. I just thought this game was interesting enough that it should be made. If it couldn’t even make an interesting game out of this, I doubt I would have succeed at other opportunities too.

GamesBeat: What your inspiration?

Shih: They say the best inspirations are drawn from other mediums. To tell the truth, I just wanted to make something as cool as Portal or Antichamber. I spent the last couple of years realizing that this is in fact, very, very hard.

GamesBeat: Can you tell me more about the story?

Shih: On the surface, the story is about a weird museum. Underneath that there’s a lot more. That’s not a great summary, but it’s really hard to explain why something is interesting without making it worse — I still need to work on that.

GamesBeat: What are the kind of challenges you’ve encountered?

Shih: To me, the biggest challenges are always the design challenges. If the design is great, then everything else — finding teammates, finding funding, finishing the game, marketing, etc, are so much easier. If the design is bad, then having those other things don’t really help that much. To me, the fundamental problem is always, “Why is my game bad and how do I make it good?”

Some specific design challenges that we’re struggling with are: How do you keep things both grounded and surreal at the same time to give puzzles and environments a humorous edge? How do you create a game narrative in a puzzle game based in a surreal world while keeping stakes but also having a sense of casualness so any plot-related elements don’t seem heavy-handed? Why are video games so hard to create?

GamesBeat: How has the game changed since you started the project?

Shih: Two feelings are always brought up with this question. On one hand, the game has gone through an unsustainable amount of narrative, art, and puzzle changes. On the other hand, the core of the game hasn’t changed all that much. We often had to go back and search for that initial feeling to make sure we didn’t lose it.

Sometimes, you create a thing that works without truly understanding why — and then you break it. The process of breaking it and understanding why you were stupid helps make the game better.

GamesBeat: What’s the indie community like where you are?

Shih: I live in Seattle right now, which has one of the largest and most vibrant indie communities! At least that’s what they tell me.

At the moment, my teammates are my biggest support. I also work out of an indie game co-working space called Indies Workshop, which has a bunch of friendly and professional game developers. If you ask a question, somebody will point you in the right direction. It’s useful because having people around to keep you grounded and let you borrow books that you never return.

GamesBeat: How do you avoid burnout?

Shih: There are a lot of different reasons that lead to burnout. I was a solo dev for a while, and for me it was pretty tough for me to maintain a healthy work life balance. I felt like I was working all the time and also not making enough progress. It became an unhealthy cycle where I felt lost.

To get out of it, I found teammates who could keep me accountable and move things forward. I still constantly worry about progress, but at least I know things are moving forward. Like everyone else, I have a love-hate relationship with deadlines.

GamesBeat: Who is the audience for this game? What do you want them to take away from it?

Shih: The audience for this game are people who are interested in new game experiences. I’m lucky that a lot of video game players right now seem to fall into this category.

This game is less about logical puzzles and more about how weird things are. A kind of personal goal I have is to show that even with all the video games that have been created so far, there’s still more space for video games to feel surprising and magical and new.

This also turned out to be extremely difficult so don’t take my word for it.

GamesBeat: Are you considering crowdfunding the project?

Shih: We decided not to crowdfund the game. If we had a clear idea of what the game would be and how long it would take to complete it, I think we would have crowdfunded the game. However, throughout development it’s never been crystal clear and last people I would want to disappoint are the people who were the first excited about the game.

In other words, if I was better at my job and at design I probably would have crowdfunded the game!

IndieBeat is GamesBeat reporter Stephanie Chan’s new weekly column on in-progress indie projects. If you’d like to pitch a project or just say hi, you can reach her at stephanie@venturebeat.com.