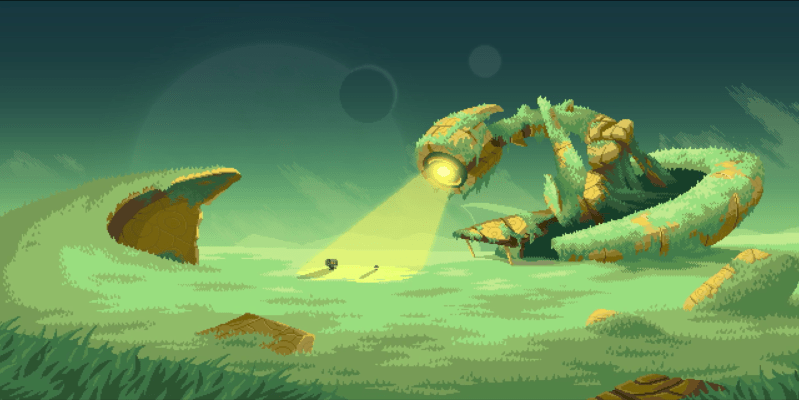

A game about an intergalactic insurance salesman could only go in a few different ways. One is the Douglas Adams route with wackiness in outer space and planetoid construction sites. The other is Springloaded Software‘s Obelus, which is a somewhat grim though cheekily surreal look at what humanity’s future might have in store. It’s a science-fiction tale that tackles our relationship with artificial intelligence, complacency versus happiness, and the meaning of it all. It’s currently raising funds on the crowdfunding platform Fig, and it’s in the last week of its campaign.

Based in Singapore, Springloaded is a team of four plus founder James Barnard. He was a lead designer at LucasArts before he struck out and founded Springloaded in 2012.

“When I left LucasArts I was like, ‘I’ll make games on my own!'” said Barnard in a phone call with GamesBeat. “So I picked up coding and I made like five tiny games on my own. I did everything on those. And then we got a publishing deal and I carried on programming. These days I write a lot of code, most of the code in our games, and I do all the music and work on the design stuff. This game is particularly mine as far as design goes because I’m so passionate about it.”

Originally named “Goliath,” Obelus is on its surface about a man who travels the galaxy in a mech suit, meets people from all over, and sells insurance. It explores ideas that Barnard started thinking about while making mobile games. Springloaded has developed several, such as The Last Vikings, and a large part of succeeding in the mobile market is data collection. But data collection isn’t always something that people reject; in fact, some embrace it.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

“Those things will be accepted by people because they’re things we think would make our lives better,” said Barnard. “And then in the end they wouldn’t make our lives better because we wouldn’t know what we felt anymore. The world around us would be manipulated to make us feel a certain way. We wouldn’t necessarily feel that thing. I think that’s actually not that far away in our future, and that’s really scary.”

Here is an edited transcript of our interview.

James Barnard: I was talking to someone about the game. They read a synopsis I wrote, and they said, “Where’s the joy?” [Laughs] Well, it’s kind of ironic that you’re in this ridiculous situation. It’s kind of funny if you’re willing to open yourself up to that. The game just gets more depressing as you go through it, I guess?

GamesBeat: I guess there’s nothing fun about insurance.

Barnard: Yeah. Well, the conversations you have with the people you meet are kind of ridiculous. You meet people who are tinfoil-hat-wearing, “I’m scared of everyone spying on me, I’m scared of the world manipulating me, I’m scared of people trying to sell me things,” everything. But it’s just—in the game, those people turn out to not be crazy. They’re telling the truth about everything. In much the same way, people taping over their laptop cameras—we feel like we’re super paranoid, but there may be a valid reason to do it.

GamesBeat: Is that the inspiration for the game? I know in the campaign page it says that you tackle AI and big data. Is it all these modern paranoias that we experience?

Barnard: Kind of. It actually comes from making mobile games. Mobile games are all about analytics that track our users. We put all these little data points in and collect everything. Then, as designers, we’re supposed to look at those data points and decide how to change our game to keep players addicted for longer and all that stuff. Obviously I started thinking about how—this was about five years ago, I guess, when I started doing it. I thought, well, if you write an algorithm that has an objective of making more money, and it tracks all these things and balances a game individually for people without even understanding what it’s balancing, you could potentially make a game that makes people spend more money.

A lot of stuff is just about patterns. By following humans’ patterns we can ultimately understand everything about them without really knowing anything about them. Interestingly—I think if I know the things that make you feel motivated, like people put on the Rocky soundtrack when they’re going to exercise or whatever it is—if you find enough of those things about individuals, rather than people as a global mass, I think you can make people feel excited about going to work, make people feel lots of love for their partner, or whatever it is. Those things will be accepted by people because they’re things we think would make our lives better. And then in the end they wouldn’t make our lives better because we wouldn’t know what we felt anymore. The world around us would be manipulated to make us feel a certain way. We wouldn’t necessarily feel that thing. I think that’s actually not that far away in our future, and that’s really scary.

So even though the game is set far in the future, I think it’s already really happening all around us. Maybe I sound like a crazy tinfoil hat person, but—it bothers me and I wanted to make a game that could communicate those ideas to people. What’s funny is I started thinking about the game three or four years ago. I started making something. When I told people about this theory, they’re like, no, it’s nonsense. Now I tell people about it and they’re more like, yeah, yeah, I can see that. My one worry is that by the time I finish the game everyone will be so deep into it, it won’t even be an interesting subject anymore. Across the world, oh yeah, that’s how the world works.

GamesBeat: It becomes a slice-of-life story.

Barnard: Yeah! Yesterday there was an ad company that fired a load of people and stripped down because they said the ad business has changed so much that people are now using programmatic advertising to target users, instead of, I’ll just advertise my game, or advertise my Coke can. They’re using AI to deliver adverts, and it’s to such an extent that we’re seeing people in traditional advertising businesses firing everyone. It’s really scary, because it means that the people with the most money, who have the most data, are able to basically rule the world by—say there are people in my game that are really good spenders or something, that allow me to make my indie free-to-play game into a business by using all this programmatic advertising and stuff that people spend a lot of money on. Eventually they’ll be able to mine all the people out of my game by figuring out what they respond to. It doesn’t seem that insidious as a thing. But when you start to think about the greater implications of it—they can track who you are as a consumer across the internet. If you turn on a mobile game or you’re reading a website, maybe they’ll end up—they’re talking about targeting adverts for the same product to different people.

That’s already starting to happen, and it’s exactly the thing the game tries to highlight. What are you if you’re just being sold things or being told to do things in a way that makes you do them? Is it actually you anymore making decisions? A lot of people don’t necessarily feel this way. They think it’s okay. Well, they’re just giving me a thing I like more quickly. I don’t have to spend so long choosing. But I don’t really agree with that. I think it’s a bit crap. [laughs] If I can make people, when they’re playing the game, think about these concepts in the same way I do, regardless of if it’s true or not, who cares? If they can at least see my point of view when they’re playing the game, that would be really cool. I want this feeling of helplessness against the AI to come across in the game.

GamesBeat: As the insurance salesman, then, are you trying to tailor your pitch to these characters that you encounter? How does that work? Are you trying to be like the programmatic ads and get people to buy insurance?

Barnard: At the beginning of the game you’re quite happy. You’re just there living your perfectly ideal, content life, and the computer tells you things and you do them and you believe everything it says. These people that you’re selling insurance to, because they’re so terrified of computers and AI and stuff, they have defensive mechanisms, so your AI can’t talk to you. Different types of different people, but basically you’ll end up alone and away from the AI when you go and talk to them.

So you’re trying to apply the things that the AI has told you, before going in, and you’re trying to use these soulless sales pitches, just like the ones we get on phones today, and then these guys will be like, screw you man, you’re brainwashed by the AI. They sow these seeds of doubt and question in your mind. And then they’ll say things like, just wait, he’ll say this to you. And then you’ll go back and he’ll say that to you.

So the player is supposed to start trying to fight back against the AI. And you’ll be completely—I’m not sure whether or not the game is going to be entirely possible to play without ever fighting back, just playing through in ignorant happy bliss. But obviously curious players will start pushing at the edges of the thing.

GamesBeat: Why did you change the name? What does “Obelus” mean in the context of this world?

Barnard: I thought Goliath was a really good name, because I wanted people to think that Goliath was either the mech or some massive opponent you would come up against. I wanted it to be deliberately vague. In my mind Goliath was actually the insurmountable power of AI, you know?

But it’s trademarked for use in video games by some company, so we had to change it. Obelus —I’m happy with the term “obelus.” I don’t think it sounds as strong as Goliath, because people don’t know how to pronounce it. They don’t remember the word because it’s weird.

The meaning is really cool in the context of the game, but nobody knows it. Obelus is actually a division symbol. That’s called an “obelus.” The line with the two dots above and below? Obviously I’m talking about a division in lots of things, but primarily our free will. It’s being divided away from us, leaving us. The division of us and our free will. The choices we make are not going to be our own.

The other thing obelus was used for in the past, the origination of the symbol, is that if people were reading a book or a manuscript or something and they didn’t believe what was written in the book – there was a chapter or a paragraph they thought was questionable – they would mark it with an obelus. The whole game is about that, about the computer talking to you and you questioning whether what the computer is saying is true or not. Or if it’s just there to make you do what it wants. That’s the strongest meaning of the word as it relates to the game.

GamesBeat: Would you say that Obelus is ultimately an optimistic game? Or is it sort of a Nostradamus warning about what will happen if, 200 years from now, we just roll over and give in to our fate? What’s your emotional temperature here?

Barnard: Well, to me it’s a very bleak game, because it’s how I feel. I genuinely think that in the future, the way we behave and think will be different. It’s already different to how it was 10 years ago. It’s influenced by our computers around us, our phones, things like that.

But I think in much the same way—if you were someone who lived 100 years ago and you went out every day and did exercise and spent lots of time outdoors and you looked at us today, in boxes, not outside, sitting on our asses all day, typing on machines, you’d think the world had been destroyed and the future was the worst thing ever. And so those people that wrote—that predicted that in 1975, when they started seeing computers turning up, yeah, they were right, but are we unhappy? No, we’re quite happy. We’re okay. We don’t seem particularly bothered.

I’m sure in the future, when people look back on a time like now, they’ll think, “Wow, people used to get moody and stuff?” I don’t know if it’ll be quite that extreme, but it’s potentially a very extreme version of what could happen in the future.

GamesBeat: What’s it been like being in Singapore? We don’t hear of many big games coming out of there. What’s the community like? Is it difficult to find support locally? Where do you go to interface with other developers and talk about ideas or complain about the system or whatever else you need to do?

Barnard: Well, you can’t complain about the system. It’s Singapore. The government will throw you out. [Laughs]

When I started, there were obviously other indie studios and stuff, but I just—I woke up in my bedroom and started coding and that was it. It was very isolated. On the plus side of Singapore, as I started doing more stuff, I realized that–it’s a tiny, tiny country, and there’s—if you compare it to somewhere like San Francisco, there are so many developers in San Francisco and here it’s not like that. There’s not that many of us. But we still have Google and Apple and Amazon and Microsoft, all these big companies are here and they have big offices.

Singapore is a big hub for southeast Asia. It’s a great way to meet the platform holders and stuff. It feels like a very open door in that way, which is great. That’s hard to get in other parts of the world, I think. The development scene here is growing. I’d say there are about 30 or 40 studios now. It’s still really in its infancy. I think that trying to get people to open up and go and meet each other and hang out is still challenging. We have the [International Game Developers Association]. They do events two or three times a year.

The thing that’s really cool here is there’s a lot of people who are passionate about games. The school system has lots of courses about video games. There’s a lot of really interesting stuff. Every day I seem to meet somebody that I’ve not met before who’s now making games, which is terrifying in the global scheme of how many people are making games, but it’s cool on a local scene level. There are lots of exciting things going on. We haven’t had any breakout successes. But it’s getting better. This year Cat Quest just came out, if you know that game.

GamesBeat: Do you have more people in China and Japan playing your games than, say, Western audiences?

Barnard: We’re still mostly big in Europe and America. I think my sense of humor is just too weird for other countries. [Laughs]

It’s definitely great for us to get access to understanding of other markets. That’s really cool. Here, free-to-play in mobile—mobile-wise, a lot of people play mobile games from all over the world. A lot of people here can read Japanese and speak Japanese to a degree, even though they’re Chinese or Singaporean. They’ll happily play Japanese games. I have people in my company who play Japanese games. They understand them fully and they’re really into them. I do feel like I have the full breadth of different game-playing demographics all around me.

We’ve started trying to push in Japan and that’s going okay, but in China we’ve had no success, because Chinese people apparently don’t like pixel art? I don’t know if this is true. I just don’t know. But this is what every publisher tells me.

They say, “We like your game, and if you redraw all the art in a different style it would be okay.” Apparently, because China’s access to technology is very different from people in the West, they didn’t grow up with pixel art. They didn’t play 8-bit games, and therefore pixel art is not something that has any—it doesn’t resonate with them as something that is retro and all that kinds of stuff. It doesn’t give them any memories or feelings of warmth—nostalgia, that’s the word I’m looking for. They just think it’s bad graphics. I don’t know. I find it hard to believe, because it’s not, it’s really cool.

Japan is a challenge because Japan is a very individual market. We go to the Tokyo Game Show and things like that. I’ve been to a few conferences out there.

GamesBeat: I wanted to touch quickly on Fig. It’s interesting that you’re raising on Fig as opposed to Kickstarter or Indiegogo. Can you tell me about that decision?

Barnard: We tried a Kickstarter ages ago. I didn’t really put very much effort into it, and it totally didn’t work. I thought—basically I was making a game that I thought would be a guaranteed success. I’m asking for so little money. It’s going to work. I didn’t know anything about crowdfunding and I failed hugely.

What Fig offered when I spoke to them was one-on-one support. They’re going to work with us to make sure the campaign’s correct. They’re going to promote it and make sure that, basically, we got all the knowledge they’ve earned through doing lots of campaigns themselves. It’s been like that. It’s been really good. We’ve had quite a lot of conference calls where we go through the assets I put on the store. The trailer that’s on there now is the second trailer I’ve made. The first trailer was generally regarded as suck-tacular.

The tough thing about crowdfunding is the amount of effort you have to put in. Preparing the campaign, obviously you do a lot of work. You have to build a big chunk of the game. Looking at other people’s crowdfunding campaigns, the ones that we were kind of inspired by, things like Narita Boy and Hyper Light Drifter—it looks like they’ve finished the game! When you watch the trailer you’re like, “Wow, that’s the whole game.”

If I were to do it again, if Fig doesn’t go through, I think we’d just carry on developing the game in down time, messing around, and we’d do a campaign when we were in more of a situation where the game was closer to being its final vision. But at that point, you don’t know if you need the funding. It’s a bit strange. I’m really excited, though. I hope I can get to make this thing and freak people out. Make them throw their computers in the toilet, through their phones out the window, things like that. Obviously, I don’t really want that. I’m trying to come up with some inspirational quote for you to close your thing with, but that’s not it, really.

IndieBeat is GamesBeat reporter Stephanie Chan’s new weekly column on in-progress indie projects. If you’d like to pitch a project or just say hi, you can reach her at stephanie@venturebeat.com.