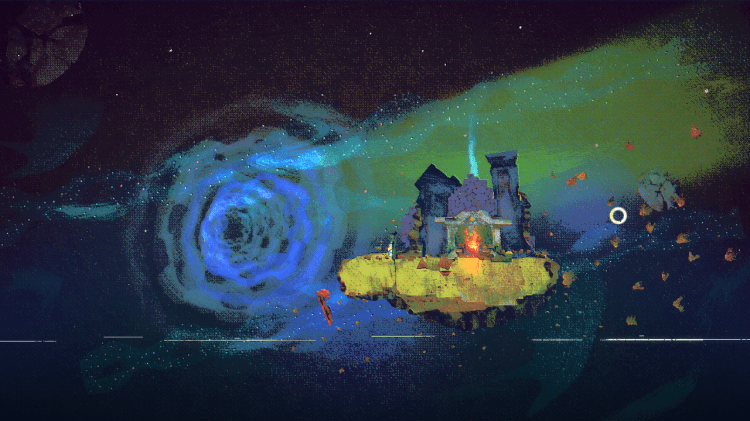

Totem Teller is a glitchy, beautiful fairy-tale world that invites the player to be the storyteller. It’s Australian studio Grinning Pickle’s debut, and it’s tentatively slated to come out late this year on PC and Xbox One, with potential launches on other consoles.

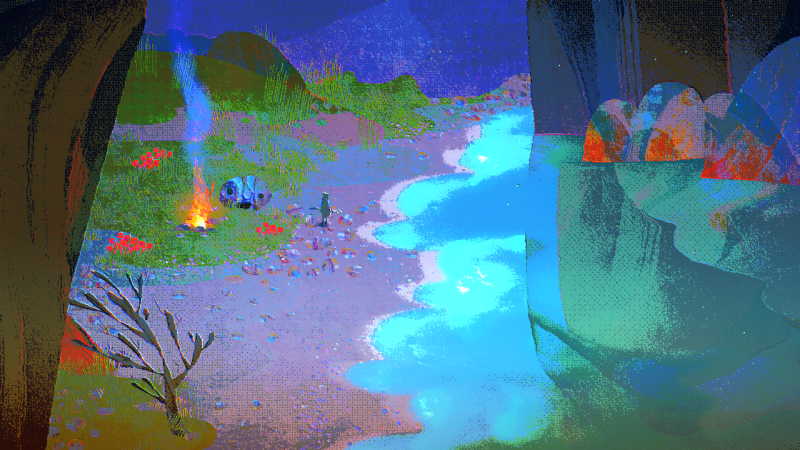

The goal is to create space for the player to ask questions and interpret the stories they hear as they choose. As they wander through the colorful slipstream environment, punctuated with static and shifting hues, they’ll meet characters and solve puzzles that have to do with a mix of mythology and folklore. Some are drawn from real tales, while the studio invented others. At the end of each section, the player can create their own retelling of the story — and there’s no right or wrong version.

A two-person team is creating Totem Teller’s mysteries: Ben Kerslake and Jerry Verhoeven, who met at American McGee’s studio Spicy Horse in Shanghai, China. Kerslake was the creative director on Alice: Madness Returns when Verhoeven joined as an intern, and the two hit it off. It was a hectic period of growth for the company, which ballooned from 15 people to 100. Then Spicy Horse pivoted to free-to-play games, and Verhoeven and Kerslake both would go on to leave for one reason or another. They kept in touch and batted around the idea of working on games with just the two of them.

Kerslake took a break from games to work at Autodesk and save up money for when he and Verhoeven knew they’d want to start up their own independent studio. They frequently brainstormed and worked on game jam projects. An initial prototype of Totem Teller emerged from one such game jam, and Kerslake says they knew that this was the one that was worth quitting their day jobs for.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

“For me, [Totem Teller is] definitely the most honest thing I’ve ever made, artistically and technically,” said Kerslake in a phone call with GamesBeat. “That’s probably the core of it. You feel different when you’ve found something like that, because it’s so rare as a creator.”

Here is an edited transcript of our interview.

GamesBeat: How would you define a good or healthy creative working relationship? You’ve worked with a lot of people in large teams, so what are you looking for out of a working relationship?

Kerslake: It’s similar to what I’d look for in building or running a team. That’s a balance of skill sets, but also of personal traits and dispositions. It’s just that on a smaller scale. It helps if you have two people like we are that are fairly multidiscipline, but also have gaps in their ability and experience that the other person can perfectly fill. And also personality traits that can balance each other out.

From a technical viewpoint, Jerry is priceless, just to properly define our current roles. As you might expect, coming from a creative, artistic, level design background, I’m essentially all asset production and level construction and gameplay implementation. Jerry is code and tools and, to an extent, technical art. His professional background is technical art, but I do a lot more of that.

In this case he’s more on the technical side of technical art, purely looking at shaders and effects, giving me the tools I need to visually prototype and work and develop art within Unity as much as possible. That’s our thing. I think we try to move as much of our work process into the engine, but just to get back to your question, it’s that complementary angle. We complement each other perfectly.

A high value thing for me is that he’ll criticize me. Having been in lead positions and assuming that creative direction role in the studio, you tend to get used to being the one that guides people and steers them toward what can help them be most successful in their work. No one tends to do that for you in that role. He had a natural inclination to do that, even when he was at the studio. I think it’s also a very Dutch trait, to be that sort of uncensored in your opinions and your critique, which for some people could be a bit hard-edged, but it’s perfect for me. I know that when he sees something that’s not good enough or that he thinks doesn’t fit our shared vision, he’ll say so. He won’t hold back. And on the flip side to that, I know that when he does compliment the work I do, it’s more meaningful and encouraging.

GamesBeat: Can you talk about why Totem Teller was the one that you decided, “All right, this game is what we’re willing to leave our day jobs for”?

Kerslake: It’s funny. As absolutely true as that feeling is, when you have it, it is a really difficult one to quantify or draw a line around. I would say that—before we decided to do that, we had put a lot of work into some other prototypes, to the extent that they certainly could have been released. Quality-wise.

But they lacked what Totem Teller has, which is honesty, in terms of, this is an honest expression, creatively, technically, of something we both feel we want to make, and also could not make under different circumstances than the ones we’re in. For me, that’s definitely the most honest thing I’ve ever made, artistically and technically. That’s probably the core of it. You feel different when you’ve found something like that, because it’s so rare as a creator. In all the work I’ve done, I don’t think I’ve ever felt like, from the underlying themes to the gameplay to the visuals of course, this is being as honest as I want to express.

GamesBeat: Speaking of inspiration, can you tell me more about the inspiration for Totem Teller, what the story or general idea behind it is?

Kerslake: There are two main pillars I always lean on. The first one, which was the basis for the original prototype for the jam that this originated from, was about something we both enjoyed in travel and hiking and discovery, which I think — there’s a lot of great games over the last five years or so trying to nail the exhilaration of discovering something unguided. That’s the whole, to an extent, walking simulator movement, but also lots of hybrid games that aren’t purely the action of walking, but certainly focused on something other than interacting with the world with a gun or a weapon. Trying to capture that feeling that we know that we feel in real life when we commune with nature, or even walk around a new city.

We’re both big travelers, and obviously having been expats for a long time, traveled a lot during that time—I think it’s natural as a creator to want to capture that and share it. That was the beginning. The prototype was purely about creating a really big environment, creating some points of discovery within, and connecting them with some narrative, but allowing the narrative to be — the player expressing, through their interaction with the world, what their own — I’ve always enjoyed traditional storytelling within games, but I’ve never felt like telling the kind of story you’d find in a film or a novel would be the type of story that’s of games. I think the type of storytelling that’s absolutely of games is the one that involves a degree of interaction and personal reflection, that comes from the player.

We wanted to create a kind of environment where the player could self-guide. You’re very familiar, I suppose, with that whole raft of games attempting to do that. That was an area that we didn’t get a lot of chance to explore in our professional careers, too, that we perhaps wanted to. I definitely tried to inject some of this into Alice, but it was very hard to fight for those sections at the time, more walking simulator-y. I think that’s just been something inside me that I enjoy in the world, so I wanted to have a chance to capture it in a game.

So that’s one pillar, the whole exploration and discovery and freedom and lack of guidance, lack of sit-and-watch-it, sit-and-consume-it style of narrative. The other one certainly is the art and the representation of the world, the compression glitch and recomposition theme. That comes from a couple of places. It comes from my background playing games on systems like the Amiga and the Commodore 64, earlier PCs, where a lot of games used acquired art, scanned art, that was seriously down-sampled or had palette reduction and other compression applied to it.

Even in my work as a digital artist, seeing my own work downsized or printed, or doing actual physical printmaking, the transformative process of taking something you’d drawn and watching it become something that was not entirely your own — in the printing process you have color offset, imperfect prints, all this, and then in the digital realm you have GIF, JPEG, all kinds of lossy compression that take your work and reinterpret it for you, and in doing so let you see it differently than perhaps you could alone, which is a rare treat for a creator.

You can never really gauge your work that way, unless you wait 25 years and look at it again, or if it’s been through the processing and come out the other side as something unfamiliar. I always found a beauty in that transformative process, and I wanted to capture that. One of the key themes in the game is trying to be in a space of creative inspiration. Not so much after the story has been written or told, but the moments between when it’s taking form and could be one of many different versions — eventually you have to settle on that, just like you do with any piece of creative work.

There’s this wonderful space of potential in creation that you love to wallow in as a creator, because you’ve not yet committed the thing. You get the idea and it feels fresh. It’s beautiful to you and you haven’t given it away yet. A lot of creative work makes me feel that way at times, but especially games. It always resolves into a kind of — you start to see the ones and zeroes, the game mechanics. The art and that side of the experience falls away in favor of the mechanical aspects. I think keeping something always transforming through glitch and compression and a lot of different ways means that you’re constantly having to reinterpret what you’re seeing, and hopefully holding the player in that space of wonder. That’s going to be a goal.

GamesBeat: Is the player interacting with the environment, solving puzzles and observing how they change the environment and how the environment changes them? How are you crafting this experience for the player?

Kerslake: Structurally, the world is divided into three very large areas that are themed in a mashup of different mythology and folklore sources. But within these areas you’ll find interactive sequences, puzzles essentially, that let you resolve different elements of a mixed-up story.

Each area is split into two distinct types of play. One is traversal, moving between spaces and finding smaller themes and interactions, just communing with nature and the environment that inspired us or that contains that sort of folklore. The other is making discoveries. Each discovery is a very small snippet, yet broken, of an actual tale, that either I’ve adapted or mashed up with — one thing I found in research is just how often you see myths and folklore crossing the lines between different cultures. To a point where sometimes it’s difficult to trace it back to the original root tale. It exists in many forms.

I’m trying to reference things that will be familiar to some people, perhaps, who are more familiar with that mythology, but not make it too obvious in terms of characters and that. I’m reinventing or retelling a lot of these things. But the references will be clear once someone collects and resolves a lot of these discoveries.

On a mechanical basis — originally, early on, it was very traditional point and click for movement and interaction, but we moved toward more of a controller scheme. We’re probably going to hit consoles, very likely, so we preferred it to control that way after we moved on from the first version.

That was interesting, because that led to more of a separation between the idea of the teller, which is, I guess, the way we referred to the player. This is where I think it gets a bit high concept. But the player character that you see and will see more of soon is the muse, a muse, that is on a journey to resolve these chunks of story, and in doing so collect inspiration that feeds actual storytellers.

You’re guiding the muse as the player, but I would say the player is somewhere between the muse, which is the avatar character, and a couple of other characters that represent storytellers. Which I can’t elaborate on too much yet, but they’re essentially channels for the actual telling of the story once all the groundwork has been done in terms of collecting these disparate parts and fueling them with inspiration and throwing them back into people’s brains and having it told as a more cohesive story, which is the ultimate resolution of an area. You get that story and can take some part in choosing its narrative flow with branching narrative.

So yeah, there’s two main sections. You’re collecting inspiration, collecting parts of story, and then resolving it into a telling. At the moment, I’m not sure how many of those there will be per area. At least one. But I’d say the only part of the gameplay I’m not 100 percent clear on yet is how that final retelling takes place.

We’d assumed it would be a kind of branching dialogue, which we have the system set up for, where you take a kind of editorial role in choosing how to interpret the themes that you’ve collected, that you’ve fixed, and choose what that means within the context of the story you’re retelling. But I really don’t want it to feel too much like what’s typical of branching systems in terms of obvious choices or rights and wrongs. That was definitely the case from day one. There’s just what the player chooses to retell based on the experience they’ve had exploring, resolving, and having a guess, going with their gut, about what these pieces mean.

Making a story from that had to feel like any answer was right, because that was their creative act — that’s one part where it’s difficult to do without feeling trite. There’s a lot of interesting branching in smaller and larger games out there, but the mechanics are very laid bare at that point. It’s one of those things where if I can’t resolve it, I feel like I’m doing a disservice to the other portion of the game, which is the bulk of play — it would be reduced or cut. But I think it’s important that I give players a chance to experience a cohesive result, I think.

This is how I think a lot of people work, and certainly I do, doing something creatively. You don’t just go from A to B to C and all the way to Z. You find B and M and L and they’re all right, they feel good, but you’re not sure how everything’s connected in between yet. You just know that these things work in and of themselves, and you trust, to an extent, or have faith that the connective tissue will form and the idea will become whole. That’s the way I want the player to work back to it.

I go into an area and it’s beautiful, it’s mysterious, I know there’s something here. I start to find pieces. They mean something. I’m not sure exactly what, but when I find more of them, when I resolve more of them, when I discover more and fix more of this, through the interaction I start to imagine how these things connect. Or perhaps there’s something familiar to me because I know this particular myth or folktale. I start to take guesses and leaps, and when I get to that ultimate retelling moment, I’m confident to make choices based on those guesses, assumptions, gut feelings that I’ve built up in that other section of play.

GamesBeat: Is it hard to get players into this quiet space where they can be reflective and interpret the game as they themselves interpret it? Is it hard to keep them from second-guessing — like, “The developer wants me to go here, so this is the way I’m supposed to go.”

Kerslake: This question gets at the core of another inspiration for us in making it. It’s a challenge for a designer. I think the assumption from a lot of players, perhaps, the audience in general, is that something that’s stripped of mechanical things becomes easier to make, simpler somehow. But that’s not the case.

Coming from having made things with lots of mechanics, that are focus tested and honed to that feedback, tutorials that have been built and rebuilt a thousand times to make sure no one puts the game back on the shelf, all that thing, that whole side of design, that’s very grueling. In doing that kind of design you tend to milk a lot of these moments. You take a lot of player agency away, and that’s absolutely the goal, unfortunately, even to this day. That’s where you’ve seen a bit of kickback in areas of design, of removing guidance, removing and letting the player discover things and make mistakes and stumble upon things.

Even in mainstream games now you see it folding back into design, especially Nintendo. They made a very clear statement with both Zelda and Mario in that regard. Very traditional setups, tutorials, and mechanics, but certainly a lot to discover, a lot of untold things, a lot of general freedom they’ve provided. That and a lot of indie games have fed into the idea that it is thrilling, again, to just discover things seemingly by accident.

But that’s the thing, because even when you are, you’re not. The designer is still there. They just have to use more subtle cues, rely more on things like topography, level design, visual cues, subtle things that lead the player without leading them. Knowing where branching paths through the environment, or other things mechanically, diverge and converge.

So it’s a challenge, to remove mechanics you can lean on, combat mechanics you can lean on, platform mechanics you can lean on. If you do them right, you juice them up, they feel good. Just doing those actions feels good. When you have less of those to play around with, you’re left with the challenge of making the experience of being in a place engaging, which means you have to put the effort into different places. That’s a challenge I’m really enjoying, and that’s the kind of game I like to play now, the game I want to be making. I think it’s exciting.

I don’t think there’s been a game that’s perfectly captured that feeling, I feel, that’s out there yet. And I don’t think I will capture that perfectly either, but it excites me that there are so many people trying. Someone or someones is going to get there and perfectly capture that feeling of being outside in a new place and finding something and maintain it for the whole game.

That’s the other trick, to keep that going, because if you play anything long enough you do start to see through it. I think removing all of those things, that’s really—if that’s all that we achieve, beyond any other mechanical arcs and completion arcs and progression, if I manage to hold somebody in that space for a good portion of the game, then that would be a big success, because I think it’s really rare to feel that way, to not see the box you’re in and just be able to let go and be in a place.

You have to do things to encourage it, too. When it comes to games like this, it’s almost like you have to provide a cue of permission to the player. It’s okay to really stop and smell the roses. This is a game about doing that. So please do that. It’s all part of a big—I don’t want to say a disappointment, but having worked on larger games and games of all different sizes, seeing all the effort that goes into creating worlds, you can absolutely diffuse that with mechanical design and how you expose it.

Every level designer and level artist I’ve ever worked with has put a lot of effort into creating wonderful things, into storytelling indirectly and indirect means of guiding the player, and again, it can all just be thrown in the bin when you just tell the player exactly what to do, where to go, where to look. Then you’re telling them, please ignore the world. It’s just a container for you to go through the motions that are familiar, or tap into familiar patterns for you. So together we can say, no, this is a world that’s unique, it’s worth looking at, someone has been in every corner of this and carefully arranged this just in case you look at it. So feel free. That’s an effort of visual design and audio design as well, because pacing—you have to give them the cues to let them know that this is a quiet walk. Nothing’s going to jump out at you.

IndieBeat is GamesBeat reporter Stephanie Chan’s new weekly column on in-progress indie projects. If you’d like to pitch a project or just say hi, you can reach her at stephanie@venturebeat.com.