Poddar: I can answer this in a couple ways. One way to answer it is that the work we do is interdisciplinary. Humor isn’t something that only the writers are responsible for. It’s central to the design of the game, and therefore writers are responsible for exploring humor, but also artists and level designers and sound designers. We want our sense of humor to permeate the entire game. And the reason we’re doing that, which is the second answer I can give you, is we want the player to have fun. It sounds simple to say, but that’s our underlying motive. The way we achieve that, the process by which we try to make a humorous game, is we iterate a lot. Our work is very collaborative. We don’t have a writer who goes off in a room and does work on his own and comes back. We’re sharing our ideas. We’re putting together a pitch for a level or a character or a quest. We get input from other designers, from artists. If it seems to hit a good note with a lot of people, if it’s making other people on the team laugh, that’s a signal to me as a writer that I’m going in the right direction. I just try to do more of that. You do that long enough and eventually you get a pretty funny game at the end of it.

GamesBeat: How hard is it to keep that on track while at the same time enjoying the humor? I’ve really enjoyed the humor, but it seems like it would be distracting to make a game like this while you’re laughing a lot.

Boyarsky: It’s such a long process, developing quest lines, implementing quest lines, iterating on quest lines. I always say you lose sight of the humor, because you always know what it’s supposed to be and how you’re trying to hit it to be the most effective. We want it to be subtle in some places, overt in other places, but it should always feel like it comes from the situation and the characters. It shouldn’t feel forced. I think early on we talk about where the humor is going to be and how we’re going to present it. Then it’s a lot of nuts and bolts along the way, just getting that to work.

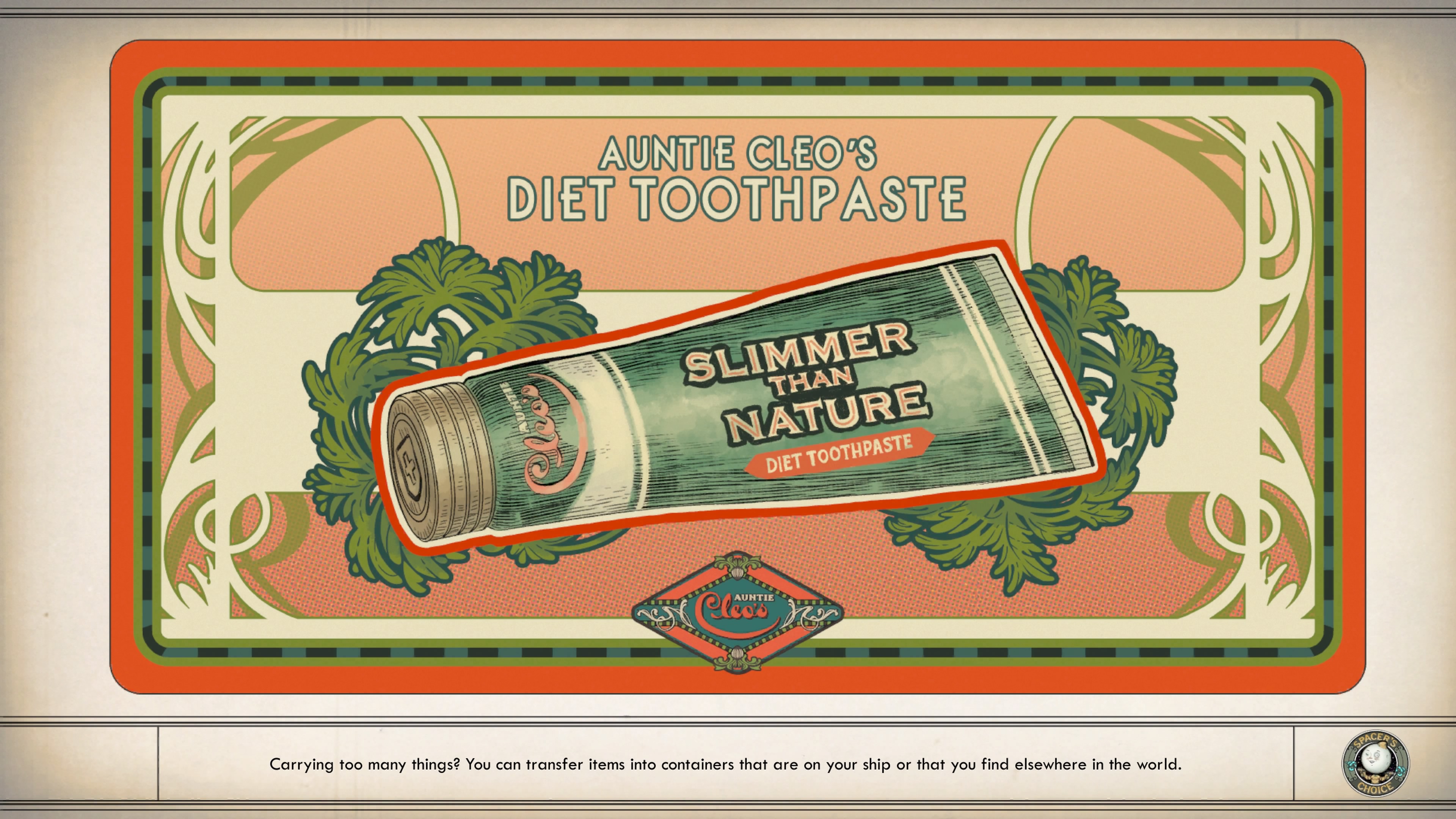

Above: Diet toothpaste is one of the many wild things about The Outer Worlds.

Poddar: I don’t necessarily think it’s distracting. Here’s the thing. There’s a lot of work that goes into actually realizing these characters, designing these quests, writing the content, writing the dialogue. If at the end of that part of the typical workday, if I was able to make somebody else on the team laugh or make myself laugh or just have a good time, then to me that’s a good indication of a game that’s going in the right direction. Game design is hard, but it should be fun. If we’re having fun and we’re on the player’s side, then there’s a good choice that the player is going to have fun once the game finally gets into their hands.

GamesBeat: Whose idea was it to come up with diet toothpaste?

Poddar: That’d be Leonard.

Boyarsky: No, it wasn’t wholly me. What happened was, that was the first area we made for the game, in the proof of concept. We were tossing around ideas for what they could be researching. Originally some of the designers had come up with something that seemed fairly standard, and Tim and I were like, no, this has to really reflect back on points that are happening in the story, on deeper themes. We started talking about diet suppressant stuff. We were trying to come up with something that seems a little silly on the surface, but could have deeper meaning. We were in a brainstorming meeting with some of the writers and Tim and I. I don’t remember who said it, but somebody threw it out there as a joke, and then all of us were immediately like, of course that’s what it has to be, because it seems really ridiculous, but there’s aspects to it in the game that turn out to be not really all that silly. There seems to be other things going on there. It checks all those boxes. It’s very silly on the surface, but it’s got some deeper things going on.

Poddar: I have a memory of working on that level, and I think Leonard popped in to the writers’ room and said, diet toothpaste, that’s what they’re researching. OK, cool. That actually works. That works pretty well. I think the reaction you had, where it’s funny and weird on the outside, that’s really what we’re going for. We’re trying to make players feel like, okay, this is hilarious, this is bizarre, this is weird, but if you stop and think about it, there’s something dark about what they’re doing and how they’re going about the research and what they could use the research for. We like layering humor on top and then something slightly unsettling just underneath.

Setting the pace

GamesBeat: Early on, you force players to make a pretty big decision when it comes to Edgewater and the deserters. Why give players that decision so early?

Boyarsky: It’s a game about decisions. We’re a game about player choice. I always think of this as a game we’re playing with the players. We’re encouraging them to take agency and make choices, and those choices affect the story. Since Edgewater is a beginner zone — it’s the first zone every player is going to see. We use that zone to establish the tone for the rest of the game. Not just the sense of humor, but also the way the game is intended to be played. We’re teaching you — hey, this is the kind of game you’re getting into. And by ending Edgewater on a very big decision, which can only go one way or another, we’re telling you two things. This is a game about decisions, and maybe you want to play through this game a couple of times to see all of them.

GamesBeat: One of my other writers, who’s also playing right now, he had a question about Edgewater. You quickly learn that you can make things better for the deserters by dealing with Thompson. Did you ever decide to obscure that possibility so that players could discover that themselves? Or did you want it to make it more clear because it was a beginner area?

Boyarsky: I think we tried to layer things in there, but we did want to make it more obvious than it might have otherwise been, so players knew what the choices were. We also wanted to play around with the player’s expectations. A lot of people, when they first get into it, if they’re not really digging into the conversations or thinking it through, it seems like a fairly cut and dried decision. But the more you think about it, the more you dig into the conversations, the more you read from the people’s journals, there’s a whole different aspect to this than you might think.

Poddar: You hit the nail on the head by saying it is a beginner area, so we do want to be more up front about the choices. I personally feel that the choice the player never knows they had, that they can’t find out they had, isn’t really a choice at all. In dealing with Thompson as a way of bringing the deserters back, we make that clear to the player, but we can’t make it clear to the player early on. We make it clear toward the end. What this does is it allows that choice to still feel like discovered content, whereas in reality we’re reasonably sure a lot of players are going to come across that choice just by design.

Boyarsky: Yeah, we don’t want to hide the choices too well.

GamesBeat: Where do you draw the line and how do you draw the line between directing players and letting them discover possibilities?

Boyarsky: That’s the million-dollar question, isn’t it? That’s something we’re constantly playing around with and iterating on. What’s discoverable, but players won’t come across? What needs to be in the player’s path so that everyone is going to see it? One of the great examples of that, I don’t want to give too much away, but it’s in some videos. When you’re going to make the choice in Edgewater, Parvati has a conversation with you laying out what your choices are and giving her opinion. When they implemented that, that really brought everything together. That was an instance where that one thing really brought the whole quest to another level. Emotionally as well as just players understanding exactly what’s at stake and what’s going on. We didn’t consider that the very first time we designed it. That was something that came later as a response to seeing people play it and seeing what they were catching or what they weren’t catching.

Poddar: It’s an iterative process. There’s a lot of finesse involved in walking the line between being too obvious and being so subtle that nobody gets it. The way I like to approach it as a writer is, there is a critical path. There is a path through the game that we want to make as clear as possible because it’s the path that leads from the beginning of the game to the end of the game. Everything that happens on that path, we lead toward clarity. We don’t want players to be lost on that path. Now, when the players go off that path, when they go off and do side quests, if they start exploring a little in Roseway or on the Groundbreaker, then I think we have more freedom to be subtle. We have freedom to hide things. We have freedom to introduce choices that may not be possible, and we do this to reward exploration and encourage players to go off the beaten path a little bit. You never know if something you discover will end up opening an option for you that you didn’t even know was there.

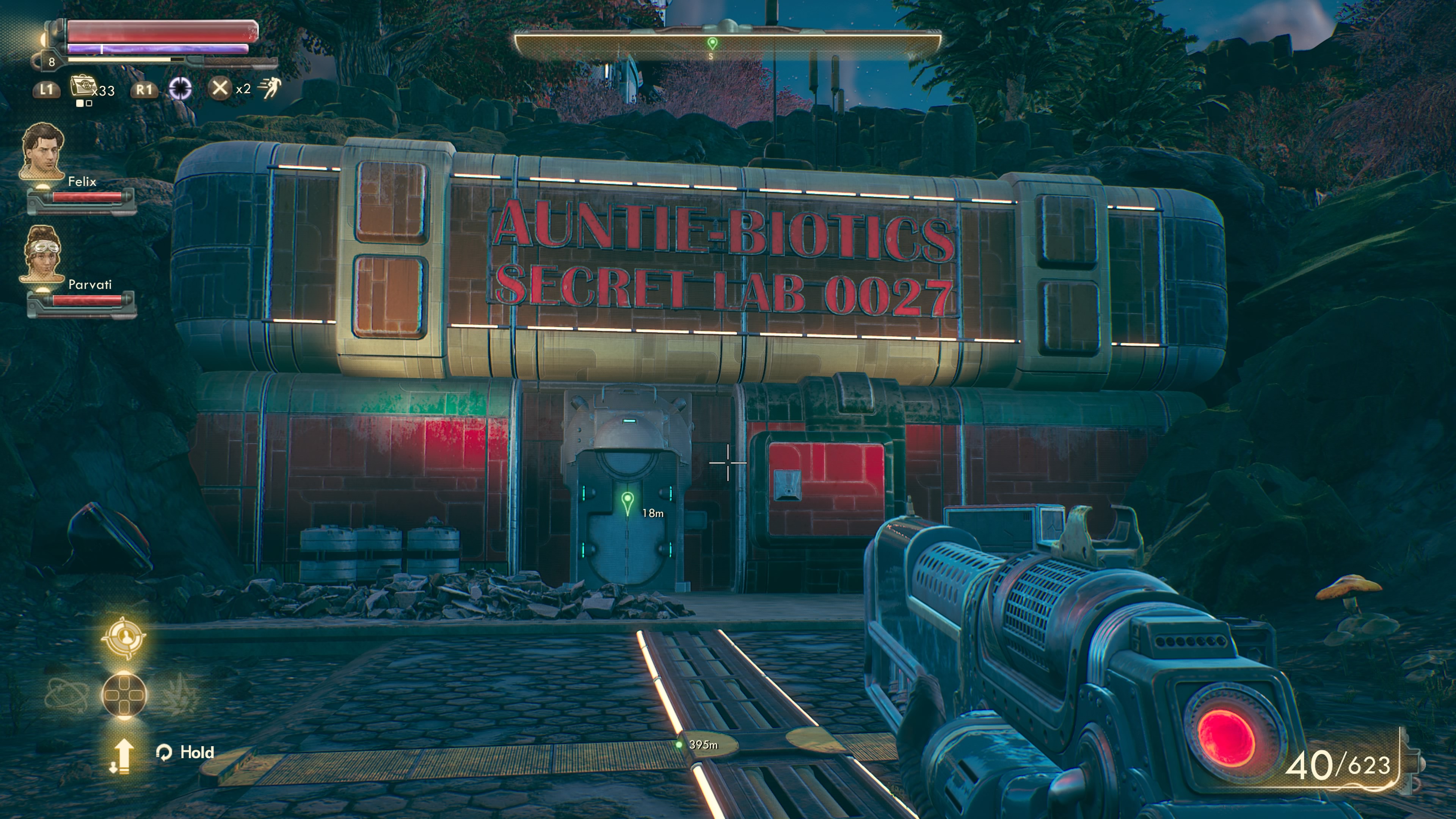

Above: Not very subtle, eh?

GamesBeat: When it comes to your humor, how difficult was it to make some things subtle and some things not? How difficult is it to balance that?

Boyarsky: Once again, it’s iteration. I think it — when you’re developing the ideas or fleshing out an area, a lot of it kind of suggests itself. And we might say, you know, we might tweak something to be more one way or the other, depending on how we feel it would work better. It’s really a–

Poddar: I think it’s impossible to tell with humor. If somebody ever figured out exactly when to be subtle and when to hit the player over the head, they’re making a lot more money than I am. With humor you can never predict — you can kind of predict, but you never really know what people are going to find funny. For that reason we try to put a lot of it in, and from a lot of different styles. You mentioned it yourself. Some of the humor is very subtle, where you have to piece things together. Some of the humor is a bit of wordplay, and some of the humor is very blunt. We do that to kind of cover our bases. There are some funny things we want every player to see and we’re reasonably sure they’re going to see it. I think the best example of that in Roseway is when you go to the secret lab and there’s a giant glowing sign that says SECRET LAB. That’s our line. That’s about as blunt as you’re ever going to get. Then if you go into Roseway and you read all the terminals and you piece things together, then there’s a lot of very subtle, implicit humor. We don’t always pick between one of the other. We try to give the player everything and let them enjoy whatever it is that they enjoy.

Boyarsky: That’s a really good example, though, because the SECRET LAB sign, we did decide that was the line that we couldn’t go past. But after a while of living with it we tweaked it even more. Originally it just said SECRET LAB, and we said, okay, there’s no reason within the world itself that this ever would have happened. We changed it so it’s SECRET LAB NUMBER — we gave it a serial number, made it feel a little bit more formal. We didn’t say this in the game, but in our brains it suggests more like — somebody got a blueprint, and on the blueprint it said, this is a secret lab. And they just made the sign. At least there’s a little subtlety in the way we’re hitting you over the head. Or at least I like to think so.

Poddar: I do know that every time we bury something, like a little bit of lore, a little snippet of something on a terminal that’s out of the way, 80% of the time our instinct is, we should make this a little bit funny. Or just very dark, or both at the same time. That’s really where the subtle, implicit humor tends to sit.

Art noveau

GamesBeat: Who on the art team came up with the idea for those gorgeous 1950s-style ads and monster drawings that go in the loading screens? That’s actually one of my favorite parts of the game.

Boyarsky: Daniel Alpert is our art director. He was the one who decided to use those as load screens, as far as I know. We have a fantastic team of concept artists who did those. They helped us define the look of the game, what it was going to be. I’m not sure who did what. I don’t want to misattribute some of them. But they really knocked it out of the park. Without them we wouldn’t have been able to really define and lock down what the look and feel of the world was on the artistic side. The decision to use them as loading screens was great, because those were all supposed to be in-world posters and ads you saw. Really bringing them to the forefront like that gives a lot more flavor to the game.

Poddar: I don’t know if you’ve seen these yet, but there are also a couple of loading screen posters which are player-reactive. Based on what you do in Edgewater, you might get one of two different loading screens that put a spin on it. We definitely had a lot of fun with those.

GamesBeat: You know, I wasn’t quite aware that was happening. Is there an example you can share?

Poddar: In Edgewater there’s one that shows a giant stalking tiger marching through Edgewater and destroying their way of life. That’s Board propaganda commenting on the fact that you put the deserters in charge. If you go the other way, you’ll get a different loading screen. It’s all Board propaganda, in a very 1940s and 1950s style.

Boyarsky: I wish we could have done more. There’s a lot for the main story arc, but the theory or the conceit behind them is that it’s all Board propaganda. If you’re doing things the Board would approve of, you’re this heroic figure. If you’re doing things the Board wouldn’t approve of, you’re painted as this evil force in the colony that’s sent there to destroy it.