Presented by Akamai

[Me]: To keep your players happy – you need to understand why they’re not.

[You]: Uh, yeah obviously. Thanks. So what?

Actually, I have a lot to say on the topic of keeping players happy. A few months back I wrote a quick post about Friction.

Friction, as I defined it, is anything that prompts your player to leave your game and look elsewhere. And you know the scare stats (right?): 95 percent of players leave a game within its first 30 days.

Fear mongering aside; I think it’s a topic so important that I even wrote an entire book about it. Today I’d like to dive a bit more into what friction means, and why it’s worth your time to read more about it.

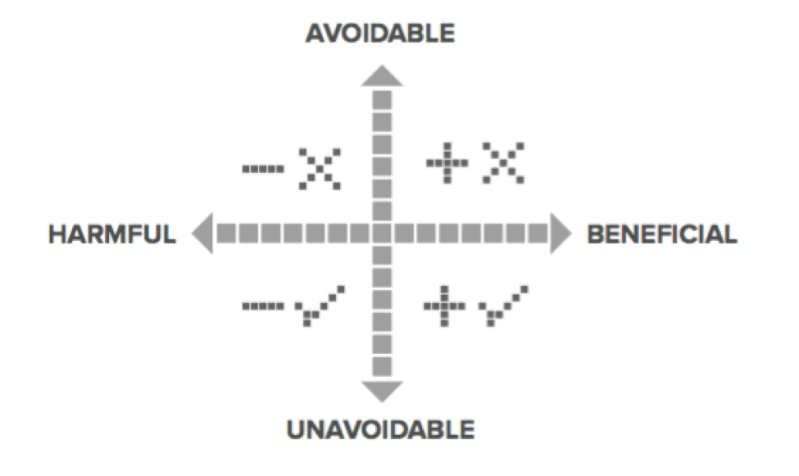

I settled on the term Friction, and the grid below, to help you build a framework to think about how best to keep your players happy. A lot of your work already goes into creating cool, fun, delightful experiences, but I’d argue that the obstacles are just as critical as the delight. Everything that gets in the way of the cool and the fun will kill the player experience.

Seeking understanding

Understanding Frictions means understanding the myriad points of contact with your players, and mapping out problem areas well in advance. This starts with game design, and goes all the way through marketing and post-launch. It helps to think about frictions in terms of consequences and outcomes.

Given enough sources or intensities of friction, players will quit. And once they’re gone, it can be very difficult to get them back. That abandonment can affect not only the specific game but the studio’s reputation and future projects for years to come.

To make it easy, I’ve laid out a straightforward way to conceptualize frictions in the grid below. This will help you to understand where they fall, how they intersect and interact, and what they mean to you. Frictionless goes deeper into helping you prepare for and manage them as they arise during your development cycles and throughout community-building and engagement, from announcement to launch and beyond.

The grid is broken up into quadrants along two axes. “Harmful” and “Beneficial” along the X-axis, and “Avoidable” and “Unavoidable” along the Y-axis. Most frictions leech player satisfaction and disrupt immersion, although some can, as noted on the grid, be good for you. Your job is to recognize the different kinds of frictions, then manage and solve for them.

So what are some examples of frictions? Consider the following:

- Cost

- Payment Method

- Game Difficulty

- Customization

- Hardware

- Language

- Time-to-play

- Accessibility Issues

Once you really get into mapping out frictions, you’ll find that many of them can end up in multiple places on the grid. Aha. There’s the rub (that’s a friction joke in case you missed it). You goal is to identify those that end up on the “harmful” side of the grid, and figure out how to flip them over to beneficial.

Is this a really difficult game (a la Dark Souls)? Market it as such. You obviously have to get players to pay for your game. Make sure the price is right, or make sure it’s folded naturally into a solid freemium design.

Are your cutscenes unskippable? Fix that before launch, or patch ASAP post-launch.

Looking back at our list again — it’s a bit of a hodge-podge. It would help to add further organization. In the book, I’ve broken down sources of Friction into three different source types:

- Player Frictions

- Game Frictions

- Publisher Frictions

If we reorganize our list, we come up with:

| Player Frictions | Game Frictions | Publisher Frictions |

| Accessibility Issues | Difficulty | Cost |

| Graphics/Style | Payment Method | |

| Multi-player | Hardware | |

| Customizability | Language | |

| Repetitive Download | Time-to-play |

I’m sure just by looking at this rough grid, you’re already coming up with a host of missing items; and you’re likely already categorizing them. Good! Keep going.

For a good deal more detail on Friction, and on how to make it easy for players to find, play, and fall in love with your game; check out my book: Frictionless.

Sponsored posts are content produced by a company that is either paying for the post or has a business relationship with VentureBeat, and they’re always clearly marked. Content produced by our editorial team is never influenced by advertisers or sponsors in any way. For more information, contact sales@venturebeat.com.