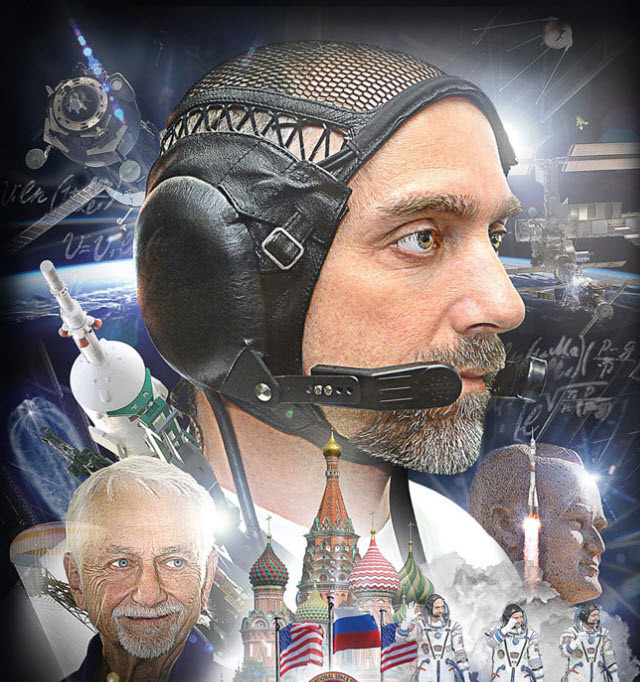

Above: Richard Garriott went into space in 2008.

GamesBeat: Your book had some details that we didn’t always know. You almost went out of business before publishing Ultima V.

Garriott: We talked about highs and lows. There are very important lessons that come out of the lows. The first machine I was particularly enamored with was the Apple II, and so, most of the early Ultimas were developed on the Apple II. When other platforms came out, I would make my own judgment as to whether I thought they’d eventually supersede or do less well than Apple’s.

When the IBM PC first came out, the original version of the IBM PC in America had a bit of a faster processor, a bit more memory, but it had this chiclet-style keyboard that I thought wasn’t very good to interact with. I thought the DOS operating system was confusing. I just felt that Apple had a strong enough lead that it would ultimately win the day. I kept Ultima V, as well as most of our other projects that Origin was developing, focused on Apple first and then porting to a variety of other platforms.

About halfway through the development of Ultima V and three or four other projects, it became obvious that the Apple market had crashed. The PC clone market had rapidly become dominant. We had no employees that were working on the IBM PC. We were going to release a bunch of games that had no market, and we knew that would put us out of business.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

We had to become a PC-first company. We had to hire a whole bunch of new employees, delay the release of all our games, and did a simple calculus. We expected this revenue to come in at the end of a particular year, and that was now pushed out six months or more. We weren’t going to survive that long. We looked into a bank loan, which wouldn’t take us to the point we needed. I had just built my first home in Austin, Texas, but I hadn’t paid for it yet. I had a construction loan. To bridge to the ship date of Ultima V, I had to put my house up as collateral. My brother and I went millions in debt with personal loans.

If we hadn’t shipped Ultima V on time and it was not successful, not only would we have been out of business, but all the value I had ever created up to that point in time in the industry would be gone, and I’d have a huge amount of debt. Ultima V, by the way, is the only game I think I ever shipped on time — because of that pressure.

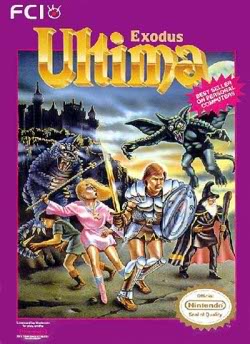

Above: Ultima IV forced you to make moral choices.

GamesBeat: You actually got in a fist fight with your brother in the office.

Garriott: That is true. Robert and I were notorious for arguing. We’re brothers. But one time, this came to a particular head. I was in his office arguing about something neither of us remember, but I’m sure I was right [laughs]. As I was angrily leaving the room, I picked up a pencil off the table that my brother insisted was his pencil, so I should leave it behind. We began to argue about the ownership of this pencil, and that broke into a brawl. We literally physically fought over who owned this pencil. And then, the pencil broke, and we both just broke out laughing at the stupidity of the whole circumstance.

As soon as we opened the door to his office, we saw that all of the other employees in the company had their heads out of their offices. “Oh my god, what’s happening to this company? There must be something really profoundly wrong coming down the pipe.” That was sort of the pinnacle of our brotherly fights. We both matured a bit that day. Our business relationships got much better.

GamesBeat: You created one of the earliest VR prototypes, something called the “Nauseator?”

Garriott: That’s right, yeah. When we first started Origin, we picked the name because we weren’t sure if we would only make games. This was before DOS. Operating systems were terrible. We were having to rewrite large portions of them just to make games work. You never know, we might make our own operating system.

If you look at the Apple II, it was simple hardware, but it had ports you could plug things into. We actually built a prototype dual joystick to make games like Crazy Climber. And in my parents’ garage we built the Nauseator. The Nauseator was a giant wooden 360-degree multi-axis simulator that could free tumble in all dimensions. We got to the point where you could strap into a chair inside. We were in the middle of putting electronics in it when we decided this was far too dangerous to continue.

This thing weighed a couple thousand pounds. It had structural beams that would move past each other with an inch of clearance. If you put your finger anywhere near it, you realized it could take body parts off. That’s when we decided that maybe we should just focus on the software side. But we did like getting in the Nauseator. We called it the Nauseator because we would put people in it and just let them free tumble. You could endanger yourself some more by manually speeding it up from the outside. It was not safe in any way you might think of the term. You’d get out of it feeling all right, but within two or three minutes, you’d tend to get sick.

Above: Ultima V.

GamesBeat: But that started a certain tradition of trying something new.

Garriott: True. If I look back at my career, especially in the early days, one of the things that was key to my success was that with each new product, we had learned so much from the earlier ones that we set all the code, all the art, all the design aside and started fresh, trying to make something that was as significantly better than the predecessor as possible. I didn’t do that because I thought it was a marketing idea. I did it because I’d be unsatisfied with what came before.

If you look at my competitors back in the day — when Ultima first came out, a couple of the other great games at the time were things like Wizardry, and then Bard’s Tale soon after that, and Might and Magic. Each Ultima was measurably better than its predecessor. It had twice as many tiles, or it went from BASIC to assembly language, or the storage it used — all those things increased measurably, significantly.

With the competition, a lot of their original games outsold my original games, but what they would do with their sequel is change the art, add some new monsters, add a new story, but technologically, it was still very similar to the original. And so, what often happened was they would sell to a subset of the people who enjoyed the previous game. My games, I would argue, were radically better each time, so they sold to larger and larger fan bases with each iteration. While that started as an accident, it became purposeful in my plans for each game going forward.

GamesBeat: Ubisoft seems to have a similar pattern today. They introduce a game with a new platform, like the Wii or Wii U, and they hope that the sequels are the ones that make the real money.

Garriott: In fact, I’m talking this afternoon about intellectual property development. Part of that is my belief that the introduction moment of a new platform is the moment where you can create new IP. Ultima, Wizardry, [Might and Magic], all of these things were created, essentially, at the beginning of all platforms.

But once a platform matures, you have the reverse problem. Once you already have Ultima, Wizardry, Might and Magic, and Bard’s Tale, an RPG no one has heard of is hard to market. That’s when people start to buy licenses, like Lord of the Rings or Star Wars, to break through the chaff. But those people who do that don’t own the IP themselves. It’s only a way to get their game to sell well. As game creators, the real opportunity — you want to create IP, you want to own the IP, and the place and time to do it is when you have the blue ocean of a new platform, where existing powerful IP is not already present. These windows open and close periodically around us, and you have to take advantage of those moments.

Above: Richard Garriott (right) visited the Titanic at the bottom of the ocean.

GamesBeat: You sold Origin to Electronic Arts and then built Destination Games and sold that to NCsoft. It seems like there’s a pattern where seasoned game developers build a company, make that brand go as far as they can, and then leave to go independent again. What do you think of that life cycle?

Garriott: What I find interesting about having had such a long time in this industry — there’s a cycle that I believe will likely continue forever. The first era of games — boxed retail products, mostly solo games — in the early days there were lots of companies. Origin was one of the top 10 — usually the tenth, but we were very pleased and proud. Origin did very well. We produced a lot of great games and made plenty of money.

But because we were selling at retail, as the retail business matured, the buyer for Walmart or Target or Amazon or anyone that you might think of, they don’t want to buy from 100 different companies or distributors. They only want to buy from a few. They want to make sure that if they buy a product from Origin, they can stock balance. If they buy one that doesn’t sell well, they want to be able to return that and buy something else instead. That means the shelf space per company becomes smaller and smaller. You have to buy your shelf space, basically. Unless you’re one of the top five, you don’t really have access to the spine-edge shelf space to sell products.

The maturing of distribution forced out anybody who wasn’t in the top three or top five. Then, when things go digital, everyone says, “Great, we don’t have to worry about shelf space!” But as that matures, you encounter the same problem in a new form. A few people today were talking about the hundreds of games that come out every month if not every day. There’s a constant stream of new products. While on one hand, it’s easy to publish, to make a game present, that does not mean anybody’s eyeballs land on it. The only way to get eyeballs looking at it is to be part of an ecosystem involving other similar game interests, something you can buy or partner your way into. That effectively brings shelf space back. The concept is similar.

Every time a new platform comes into existence, it opens up again. Not only can you make new IP, but new companies come into existence. Even though Origin gave Electronic Arts Ultima Online, one of the first great large-scale MMOs, they didn’t believe in the model. They thought the subscription model — they were gun-shy to start. Instead of making Wing Commander Online and Crusader Online, they paused. That gave an opening to new companies like Blizzard, which was already a strong developer, but then, they came in alongside NCSoft and Sony Online and all these other companies that dominated this new market segment. It was a missed opportunity for EA.

Every new platform, every new method of distribution, is an opportunity not only to create new IP but also to create new companies that compete with the older companies that might be too slow to turn and dominate that new segment.

Above: Tabula Rasa.

GamesBeat: What do you see in the rear view mirror about the Tabula Rasa project?

Garriott: I mentioned that my three favorite releases were Ultima IV, Ultima VII, and Ultima Online. The games that, despite resistance, me and the team stayed the course with our beliefs and got them out as we planned. The two rockiest releases I’ve had were Ultima VIII and Tabula Rasa. In both of those cases, they had a very similar problem, largely described as a strong difference of opinion between me or the team and the publisher.

That’s not unusual. I’ve had those differences before. But in both those cases, we did what the publisher wanted us to do. In the case of Ultima VIII, Ultima VII had been the first product we did as part of EA, but it was mostly finished before we became part of EA.

EA’s dominant business is selling sports games that they do on a yearly cadence. Every year, they release a football game at the beginning of the football season. Every year, it’s a bit better than last year, but they always make that ship date for football season. Their advice to us was, “You have to ship on time. It’s more important to ship when we expect you to ship than it is to have all the bells and whistles you think need to be there.” They believed they had data to prove it. And they now owned me so I listened. I cut the game to try to fit their schedule, the schedule we’d agreed to. That was a tragic mistake. It means the game shipped unfinished. It was buggy and unrefined.