When does entertainment become art? When does art become entertainment? Since I decided to renew my interest in gaming, I’ve been wrestling with the line between entertainment, art, and education. Part of my struggle is that high school and college force-fed so much unentertaining, dull literature, and art. Teachers and professors preached as dogma that certain books and paintings were works of art even though they added nothing introspective to my life.

But definitions of art and literature have evolved throughout history. And in the past decade, video games have become a new frontier of literary creativity. As someone who taught ancient languages and literature, I argue that it is fair to view video games as an art form worth studying in university classrooms. Games like Uncharted 2, The Last of Us, and Red Dead Redemption 2 are interactive, experiential art that deeply immerse the player in the narratives. The immersion allows the player to explore personas, themes, and moral quandaries in a way that few other art forms can match.

Why games?

There is a tendency to privilege books, plays, paintings, and cinema as high art. Unfortunately video games are often excluded from that category. But our understanding of literary masterpieces has been subject to technological change. Though we think of works like the Iliad and Odyssey as books, they were not initially read — the epics were sung by bards at festivals, meals, and other events.

The “are video games art” debate is certainly not new, but developments in video game technology and storytelling have made it more relevant than ever. Although a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed laments how Fortnite cannot compete with the imagination of a young child, I would argue that video games take our imaginations to new heights and allow us to engage with subjects and moral dilemmas as complex as any found in past literature.

As a Classics Ph.D who studied ancient languages and literature for over a decade, I believe video games should be placed in the same category as those other forms of art. Continuous improvements in gaming platforms have empowered writers, designers, and programmers to transform video game narratives into an art form.

And if video games have become an art form like other great mediums, schools and universities should become forums where students can study, explore, and discuss the themes, messaging, and stories in classrooms (and yes, these courses should count towards fulfilling a credit for their humanities requirement).

The wandering adventurer

What prompted me to consider the literary richness of video games was none other than a game itself.

Above: Uncharted 2 in Greece

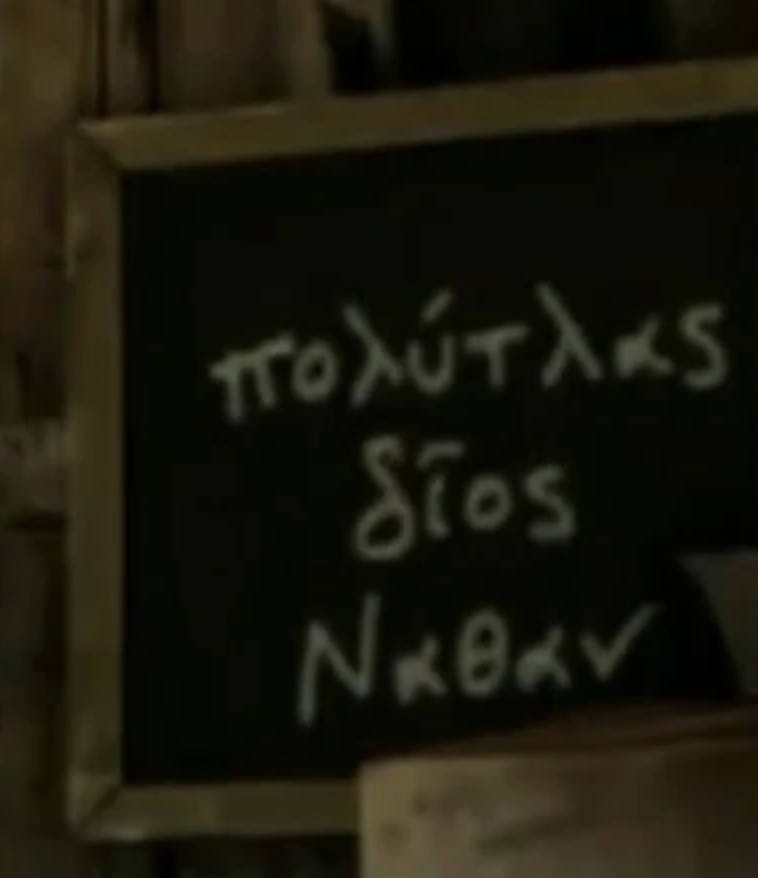

In game studio Naughty Dog’s Uncharted 2, there is an obscure, fleeting, ancient Greek Easter egg. Early in the game, there is a brief moment when Nathan Drake, the main protagonist, is speaking with another character at a beachside bar in Greece. In the background, there is a blackboard displaying prominently (of all things) a dead language.

As someone who studied and taught the language to university students, I was shocked to see this. The ancient Greek quote is not found in any ancient Greek book, inscription, or papyrus. That’s because Amy Hennig, the writer and creative director of Uncharted 2, penned the line:

Translation: “much-enduring (=polutlas), godlike (=dios) Nathan”

Above: An Ancient Greek sign in Uncharted 2, alluding to a canonical classic.

The first word polutlas means “much-enduring.” Throughout Homer’s Odyssey, the term is used with exclusive reference to one character: Odysseus. He endures much during the 10 year siege of Troy and far more during his 10 year return to his home of Ithaca. He’s the paradigm of the adventurer who journeys to distant lands encountering exotic peoples and monsters along the way.

According to Hennig, she wanted to not only reference Odysseus with this adjective but more important connect Nathan Drake with Odysseus, who adventures to far-flung locations exploring and seeing many things.

Henning is not alone in elevating the literary capabilities of video games. Recently, Peter Suderman’s New York Times’ op-ed makes the case for why Red Dead Redemption 2 is true art. Indeed, Dan Houser, Michael Unsworth, and Robert Humphries, the writers of Red Dead Redemption 2, created one of the best historical representations of the late 19th century American West in any artistic format. During the game, the player experiences post-Civil War racial tension, early cinema, the destruction of Native American cultures, the rise of the robber barons, and the toll of urbanization on rural America. Amidst that backdrop, Red Dead Redemption 2 motifs of betrayal, loyalty, and alienation.

Most of us who grew up playing video games have heard our share of naysayers attacking the platforms as a waste of time. But, at least for some games, why is it any more a waste of time than reading a novel? The Last of Us, a tale of a man named Joel and a young girl Ellie traveling across America in a zombie-filled apocalyptic world, is filled with powerful, emotional writing and a morally nebulous ending. At the end of the game, Neil Druckmann, the writer and director of The Last of Us, does not provide a right or wrong answer about the protagonist’s final decision to save Ellie’s life, even though it possibly denied humanity a cure to the disease that caused the zombie outbreak. Druckmann leaves the audience to explore the moral ambiguity of Joel’s decision. I still have not made up my mind on what I would do if I were in Joel’s shoes.

But therein lies the point.

Literature teases out the grayness of our world by putting their audience in situations that elude our moral intuition’s urge to see black and white contours. Story-driven video games are accomplishing the same feat.

Allusions and art

But do passively-experienced (oftentimes hidden) allusions justify thinking of video games as art? Allusions add layers of complexity and richness to the gaming experience. Though Hennig says that few people have commented on the Ancient Greek allusion to Homer’s Odyssey in Uncharted 2, she added the Ancient Greek quote to draw a comparison between Odysseus and Nathan Drake. What these literary references do is connect the gaming narrative to the literary past and put the story and player in a dialogue with past literature. Even if the player doesn’t realize it, part of the narrative is engaged with past literature. As a comparison, many verses in Virgil’s Aeneid are a literary reference to some event or literary work in Greek or Latin literature. Most readers don’t pick up on all of these “smart” allusions but the fact that they are adds complex layers to the literary experience — and thus worthy of further research and intellectual examination.

So why should the plot of these immersive game experiences deserve less attention than novels whose critical acclaim is often determined by critics and academics? Whether in high school or college, most of us can recall (at least) one book described as a literary masterpiece that we found unmemorable.

Should these games be studied in university classes and seminars? So far as I can tell, there is no compelling reason why a literary canon that is privileged by professors deserves special attention over the digital storytelling canvas of video games. If literature challenges us to explore human behavior, relationships, morality, and the human condition more generally, then video games have emerged in the modern era as a platform as powerful as television, cinema, and books.

Are video games violent? Yes, but no more so than the brutality seen in Odysseus’ slaughter of the suitors or more recently George R.R. Martin’s Red Wedding in A Storm of Swords (the show comes nowhere close to capturing the gruesomeness).

Video game storytelling has much room to grow and transform. How will a player navigate a moral dilemma in a future VR or AR game? The more immersive the experience, the more real the decision will feel which will only deepen the moral complexities. Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 prods the player’s moral instinct when it gives them the choice to murder innocent bystanders in a Moscow airport while the character was infiltrating a terrorist cell. It was hard enough to play the scene on a traditional console; imagine the moral scarring that a player would experience in an AR or VR environment.

As new technologies emerge that will enhance the storytelling experience, video game narratives should be a part of university courses and classroom conversations. Who knows? If Homer had access to video game technology in the 8th century BC, maybe he would have made the Iliad and Odyssey into a VR gaming experience. Who are we to tell creative storytellers what platforms they should and should not use?

Michael Zimm received his Ph.D in Classics from Yale University. He is the director of marketing at Kris-Tech Wire, a copper wire manufacturer.