Figueroa: Literacy. I love that word.

Johnson: Exactly. Just go out there in the world and talk to other people. Don’t always start from a place where you’re influenced by your own biases.

McDonald: Test, from very early stages, even concept stages, with two very important groups. One is the group of people who you want to include, and the other is subject matter experts. I worked at Schell Games for a while with Jesse Schell, where I was the narrative designer on a project called Play Forward, which was [an] HIV prevention game targeted at 11- to 14-year-old African-American students. Now, I’m about as far as you can get from an 11- to 14-year-old African-American kid, so I realized very quickly that this had to be handled very carefully. We didn’t want to be condescending or patronizing or offensive. I felt a real weight of responsibility to do that the right way.

What I did, I wrote down my story ideas and went to an after-school program where these kids hung out. I would read the story, and they’d act it out in front of me. A lot of the dialogue in that game uses the exact phrasing that these kids were using because we knew it would be relatable. It’s for these kids, so let’s include them. What I found is that when you reach out to include people, they’re so happy that you asked. They’re happy to help you because you care, and you’re trying to do the right thing. What isn’t cool about helping to design a video game?

Figueroa: It’s a barrier because if I don’t feel represented. I don’t feel that I can access that world, which is part of inclusion. In this case, we could also consider that part of difficulty because it’s a friction between me and the game if that representation isn’t there. When it comes to AbleGamers, how easy is it to reach out to the audience? You’re in a middle ground, working directly with people with disabilities as well as game developers. What is that like when it comes to reaching out around the design of difficulty?

Above: Bryce Cannon is lead engineer at Night School Studio.

Barlet: It was really hard for a long time, but I will say that in the last year to 18 months, a lot of the major studios — PlayStation, I think has done this. Through Naughty Dog and some of their work, they’ve put some accessibility guidelines out to all their first-party studios. Microsoft has done that as well for all their first-party studios. The work that AbleGamers has been doing for years — which is to show that people with disabilities are a market, that we have money we want to spend — has finally resonated.

I’m now no longer pointing out accessibility features in games. I’m kind of now pointing places where they’re missing, where I would expect them. Accessibility, especially in the last year and a half or so, has really become the norm. One of the games that came out last year, Battlefield 1, had a color-blind mode that was implemented incorrectly because they didn’t reach out to a color-blind community. They just went and read a paper online. As soon as the game came out, of course, Twitter exploded. But then, they immediately brought in people and said, “We clearly messed up. What do we do to fix it?” One of the first big patches that came out for Battlefield 1 fixed the color-blind mode.

It’s just good design. In my talk, I was talking about how EA used to always win our Game Accessibility of the Year award because they had a good design model and a budget that allowed them to create good design. Battlefield 1 has cognitive accessibility features built into it that no one ever knows about. You might not notice, but you’re always the blue object, and you’re always trying to get to a circle. No matter what team you’re on, you’re always blue, the enemy is always a diamond. This deals with color-blindness, but it also deals with cognitive issues because you don’t have to remember what side you’re on. Red is bad. Diamonds are bad. I want it to be a blue circle. That’s a cognitive accessibility feature.

Johnson: One of the greatest things I’ve seen over the past few years — the advocacy that AbleGamers has done has permeated the industry. I get to be in a place where, when I talk with our first-party developers, it’s not 101. We get to jump in a bit further ahead. They get that they have to deal with things like color-blindness, controller remapping, better subtitles. We can have a conversation about how we go beyond that. We can talk about innovative mechanics and really including a broader audience.

Barlet: To your point, I’m doing a talk at GDC this year on blind gaming, which is an area that we used to avoid because it was so hard. Now that we’ve gotten past the 101 level, where we can expect these basic things to get done, now we can start having more in-depth conversations.

Figueroa: This concept of literacy pairs so well with reaching out to communities and bringing them in to design on that ground level. When you’re designing for a specific audience, so many times our own biases bleed into that. When it comes to designing for specific audiences but across different devices, did you guys do anything different with iPad or mobile versions of your games?

Cannon: When it comes to accessibility, no, sadly. That was a very fast port. But a lot of it is just good design. I feel like you’ll get 80 to 90 percent of the way there just by designing the game well — not using tiny text on the screen, not hiding things too deeply in your UI. We tried to playtest the original game as early as possible. Halfway through the development cycle, once we had a prototype where you could move a capsule around, we would have friends and family try it out and see if it all made sense.

I’m hoping that we can do more for our next game. We didn’t do a lot of intentional design for accessibility. A lot of it was just that 80 to 90 percent. We’re a tiny studio, but we tried to design the UI well. Hopefully, we can tackle that last 10 to 20 percent for Afterparty.

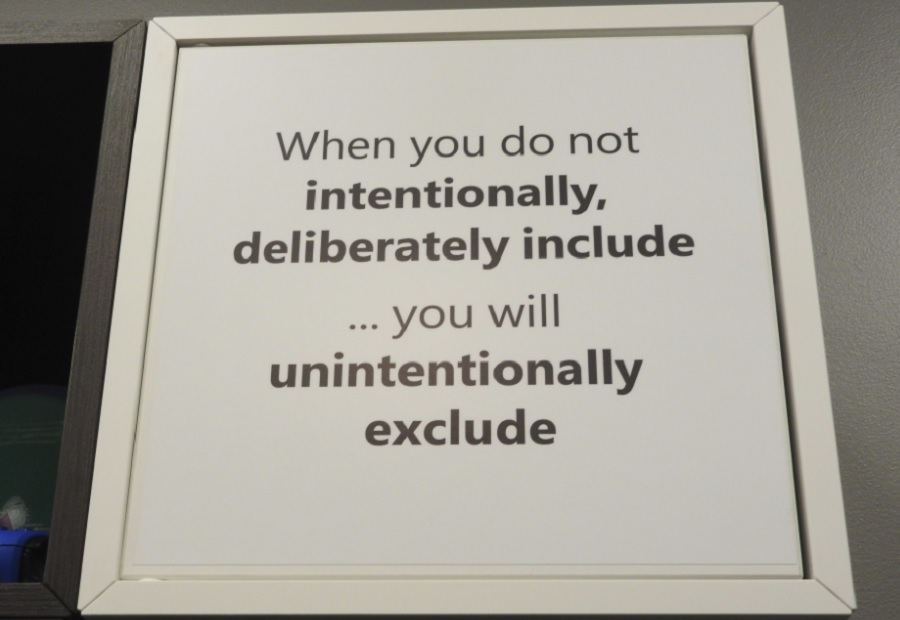

Above: A message on the wall at the Inclusive Technologies Lab.

Figueroa: Part of the same inclusion — for example, I love your talk about how there is no average. If I’m designing for an average person, that person doesn’t exist. Nobody fits into a men’s medium. The sleeves are always too long, or the hem is too short.

Johnson: We have lots of things in our world where — you would never go shopping for a car and expect to buy a small, medium, or large. Ergonomics is a well-known field. We just need to apply the learnings from that field to other things.

McDonald: A few years ago, Raph Koster wrote a book called [A Theory of Fun for Game Design], and in there, he talks about flow, how important it is to have your players maintain a state of flow. Within the last 10 years, that concept is now being taught in game programs all over the world. If you go to game-design classes, flow is a thing you learn about. We were talking, at one of our design hives — what if designing for things like empathy wasn’t just designing to make you feel good? Maybe it’s just like Raph Koster’s flow. Maybe it’s just a question of good design. That’s what I’m hearing right now from Bryant. We’re doing this because it’s good design. That’s what the answer might actually be. If you’re designing well, you’re designing for the maximum number of people.

Barlet: I think you’re onto something there. To your point, difficulty is really around the friction of flow.

Figueroa: Something like Dark Souls is a perfect example. There’s not necessarily a great flow to that game. I love that people have that mastery of skill, but if difficulty is an interruption of flow or a friction of flow, how do skill levels…?

Barlet: Flow is individual as anything else. What one person considers flow might be something you consider not flow at all.

Cannon: I think the flow chart is something like difficulty over skill level, right? As your target audience has greater skill, you can increase that difficulty. It’s not always a bad thing. Something like Dark Souls requires that high level of literacy, that high level of base…. I know how to swing a sword in a game, and I generally know that there are certain times that I’m invincible versus vulnerable. Stuff like that.

Figueroa: Even designing errors. There are so many classic games that hung on this concept of literacy, where you knew that your hitbox was just slightly off in a certain way. [Awesome Games Done Quick] just happened, where people are exploiting all these things. That’s really a kind of flow at that level.

McDonald: I need to fangirl over Cuphead for just a moment. I do not like platformers at all because I’m not skilled at them. I have rheumatoid arthritis, so at times, my hands really aren’t doing what I want them to do very well. Cuphead is a notoriously difficult game, but it was my favorite game of last year because they made failure so much fun. While everyone is complaining about how they just died again, I just found so much joy and so much whimsy in failure there. I wonder if making failure fun in some of these more difficult titles might be a consideration.

Johnson: I do think that, since we’re on this topic of flow, it’s important to recognize that state of flow. Is anyone familiar with the Mary Meeker Report? It comes out every year. It’s this bible of what’s happening in the Valley, and this year was the first year that had a huge gaming section. This is the year that the Valley decided they’re coming for games.

There’s a part in the report that specifically talks about auto-tuning difficulty to keep people in flow. If you think about the economics of the Valley and the stuff that comes out of there, it’s about eyeballs. It’s about time spent. Having people die and leave, no matter what the reason, is basically counterproductive to their business goals. They want to keep people playing. It’ll be interesting to see how games evolve in the next few years based on non-game-makers getting into gaming, basically.