Above: AbleGamers wants everyone to be able to play.

Audience: That’s kind of what we’re leaning toward? But we’re wondering if it would make an impact if we actively said that we’re trying to approach a certain community. We absolutely want to make a game for the mental-health community, but we’re also trying to make a game for people who don’t understand mental-health issues.

McDonald: What I would say to that is, market your game the way you intend to market it for the core audience, but also do side campaigns for these more targeted audiences. You’re going to want to go to the mental-health community and say, “Here was our intention with this game. We’d like to be in dialogue with you about how it can be used in these ways.”

There are researchers around the world who are looking for games to build social and emotional learning curriculums. If you can partner with those people — just like Oxenfree, they did not say that it was an empathy game. They just made their game, and I was so happy to meet him because I have a pair of Norwegian researchers who really want to talk to him. They want to do a social and emotional learning curriculum around Oxenfree that they can use to teach those in schools.

Cannon: Yeah, I would do that secondary marketing push. Your primary marketing push is to sell the game like you want to sell the game, and then, after the cat’s out of the bag, go ahead and do the secondary marketing push.

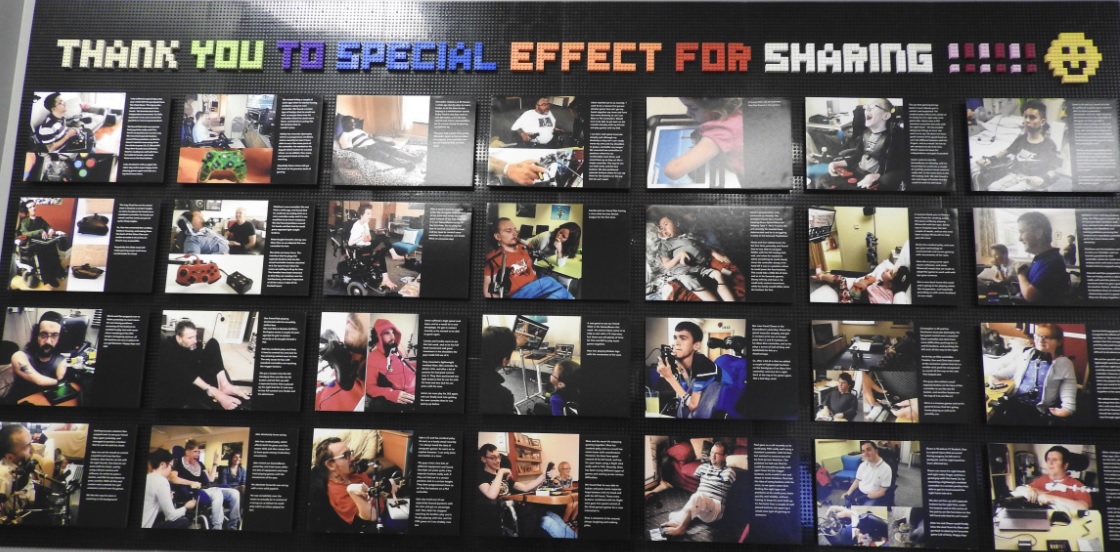

Audience: We’ve talked a lot about accessibility and building features and trying to be more inclusive. Where does cost play into that? Some things we’ve talked about are cost free, but many of them are not, particularly if the tools involved aren’t already available. How do you deal with that question?

Barlet: The AbleGamers philosophy is to make the game as accessible as you can make it while maintaining your vision and budget. If you think about accessibility early, it’s actually pretty cheap. If you try to bolt it on two weeks before release, it’s really expensive. But I’m not a believer in universal accessibility. I’m a gamer. I want your vision to be realized. If your vision doesn’t include me, I’ll be disappointed, but I’m not going to fault you if you just can’t do it.

As far as I’m concerned, I want your game to be as accessible as it can be, but no matter where I fall on whatever amazing disability spectrum, there’s content I can consume. If you’re pushing a genre and a story, I want your game to exist because it [forwards] the medium I love. If other games are based on what you’ve created that I can play, I’ll reap the rewards of what you’ve created.

McDonald: Some of it has to do with just building a good business case. The talk he gave just before this one laid out a really incredible business case for accessibility. You’re leaving money on the table if you don’t do this. I talked at GDC in 2016 about the business case for queer inclusion in games. That’s something we’re working on at iThrive: How do we build a business case for considering things like empathy and kindness in games? There’s going to be an audience for that … too. It’s just a matter of finding where the money is.

Cannon: I’ll second your point and say, definitely, start early. As a programmer, it helps when you know if you need to have UI elements change color, say, based on color-blindness settings. If you know that early on, it’s much easier to make that happen.

Barlet: Or even better, if you use symbols instead of color, or if you’re doing what’s called second channeling, where you have two ways of showing things, you don’t even have to worry about a color-blind mode at all. You’ve factored that completely out of the equation. Don’t match the red things, match the square things.

Figueroa: I’d also encourage you to push back on your tooling. Voice this to your tooling. If it’s something you’re doing in-house, make the business case to that team. If you’re using an engine that you’re paying for, like Unity or Unreal, voice these needs to them. They only do, mostly, what the audience needs, and the larger a voice you have bringing up these issues, the faster those toolings will become available to you.

Also, if you’re able and you do the tooling in house, now you have a business option to sell that tooling. You sell the game, and then, you can keep that as your market advantage, but you can also turn around and sell that tool.

Johnson: We try to encourage people to target a permanent disability or limitation and then think about the temporary and situational appearances of that limitation. If I design a game to be used by someone who has one arm, then it’s also usable by someone who’s broken an arm or who’s holding a baby. That’s actually the canonical example we use, holding a baby. When [Nintendo’s Shigeru] Miyamoto at the Apple conference said, “Look, you can play [Super Mario Run] while you’re eating a hamburger,” that’s my new one.

Audience: I’ve noticed, as I get older and have children, I appreciate more difficulty settings in games because sometimes, I just want to enjoy the story in a game. I don’t have time to die multiple times. My time’s run out. I have to go to bed and go to work again. When I was very young, you couldn’t make a game too hard for me, and now, if there’s an easy option, I’ll always jump toward that, at least the first time. Maybe this will be a trend going forward as gamers age?

Above: Deus Ex: Mankind Divided examines the augmented future.

Barlet: I talked with the lead developer of Deus Ex when it first came out. He said that a third of his team was storytellers, and the bulk of their expense was voice-over. When you first load the game, it gives you a menu that says, “Tell me a story” or “Give me a challenge, I want the hardest thing in the world.” He said the reason why they did that was, it would have been a tragedy if they spent all this time and money on storytelling and voicing that story and the first jump puzzle made you throw the controller away. Now, you hate the franchise, and you didn’t get to consume this story that the creator’s so proud of. When you go into the easy mode, it’s literally just, boom, boom, you’ve made it. It was a new IP at the time, so he wanted you to be able to get into it.

McDonald: Witcher does that. Dragon Age does that. It’s becoming very common. What I would say is, it’s interesting to take that gamer motivation profile, look at it over the course of several years, and see if your profile changes because it sounds like that’s happening. That might be an interesting study for someone. I’ve always been the adventure gamer, the story gamer. That’s never changed at all since I was 10. There’s a scholar in Germany named Hannah Marston who’s doing some work around this, the way player motivations change as people age.

Figueroa: It would be incredibly boring if our motivations never changed. As a human being, I would hope against hope that we all grow and learn and change as individuals enough….

McDonald: I don’t know. I’m cool just being the story girl [laughter]. I would be completely OK playing story games my whole life because it’s the stories that are different.

Disclosure: Casual Connect paid my way to Anaheim. Our coverage remains objective.