Games are played by more than a billion people, and games have become a $116 billion industry. But that doesn’t mean they are as accessible as they should be. I dipped into this topic on a tour of the Microsoft Inclusive Technologies Lab back in October, and I found it’s a field that is just getting started.

At the diversity symposium at Casual Connect USA 2018 in Anaheim, California, a panel of people who have thought a lot about inclusivity addressed the issue of making games more accessible.

Hollie Figueroa, developer at KinifiGames, moderated the panel, which included Bryce Johnson, senior designer at Xbox and a creator of Microsoft’s Inclusive Technologies Lab; Bryant Cannon, lead engineer at Oxenfree creator Night School Studio; Heidi McDonald, senior creative director at iThrive Games; and Mark Barlet, founder and executive director of the AbleGamers charity.

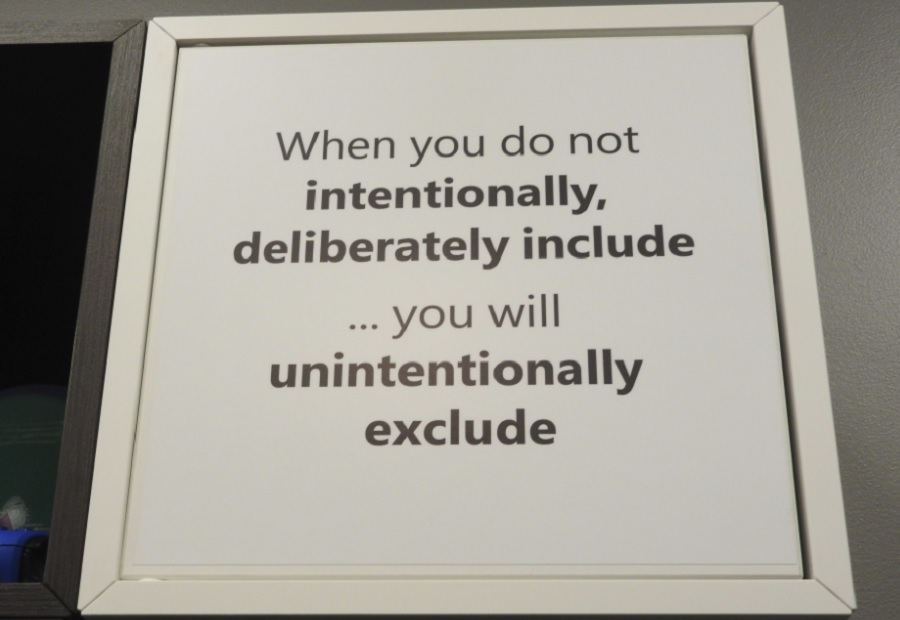

At Microsoft’s tech lab, a sign says, “When you do not intentionally, deliberately include … you will unintentionally exclude.” The lab and this panel are meant to change the perspective of game designers and challenge their assumptions about what accessibility really means.

Here’s an edited transcript of the panel’s conversation.

Above: Left to right: accessibility panelists Mark Barlet of AbleGamers, Heidi McDonald of iThrive Games, Bryce Johnson of Microsoft Inclusive Technologies Lab, Bryant Cannon of Night School Studio, and Hollie Figueroa of KinifiGames.

Hollie Figueroa: This is the product of a Twitter conversation on game accessibility, game design, game difficulty, and how they all relate to each other. I threw out a question to my colleagues, and we had some great discussion. I think we all learned something, and we wanted to continue that with some experts and applied knowledge.

Bryant Cannon: I’m a lead engineer at Night School Studio. We released a game called Oxenfree two years ago, almost today, and we’re working on a game called Afterparty that comes out next year.

Bryce Johnson: I’m a designer at Xbox, where I work with our software teams, hardware teams, and game studios, primarily around inclusive design. We try to make our products accessible to everyone.

Heidi McDonald: I’m senior creative director for an organization called iThrive. We promote the development of games that increase positive psychology practices, such as empathy and kindness. I’m the game expert on a team of scientists who are figuring out how to develop games for those outcomes.

Mark Barlet: I’m the founder and executive director of the AbleGamers charity.

Figueroa: Let’s start off by defining difficulty, which is how the conversation first started. What does difficulty mean to you? What does it mean to your users, and is that different?

Cannon: To me, difficulty has two definitions in games. First one is, who is your target audience? What is the literacy level, gaming literacy, that your audience is comfortable with? The other is when you’re scaling difficulty in the game because you’re trying to teach the player something through game mechanics. We use difficulty to set a lesson plan for teaching players those mechanics.

Johnson: The one misconception about people who advocate for accessibility in games is that they don’t want difficulty. That’s the furthest thing from the truth. Difficulty is why we play games — assonance, dissonance. The way we look at it, though, difficulty is not a single unified spectrum. It’s a bunch of independent attributes that can be applied across many facets.

When I talk to people about difficulty, I talk to them about fit a lot, this idea of custom fit difficulty. How do you tune difficulty for one person? That fit is an opportunity for us as an industry.

McDonald: I think difficulty is tied very closely to player motivation. If you look at Nick Yee’s site, Quantic Foundry, he has a really cool survey that will spin out, “Here’s one of 14 motivations that are important to you when you’re playing.” There is a motivation called mastery, and that’s the people who love core games, the people saying, “I love Dark Souls because it’s really hard.” There is going to be a class of people for whom difficulty in games is a challenge, and they love it.

Other than that, I think difficulty has to do with things that might impede your player from having an enjoyable experience of your game. If I’m a deaf person and your game is built around audio, that’s going to impact my ability to enjoy your game. Any factor that, if missing, could impede enjoyment of a game.

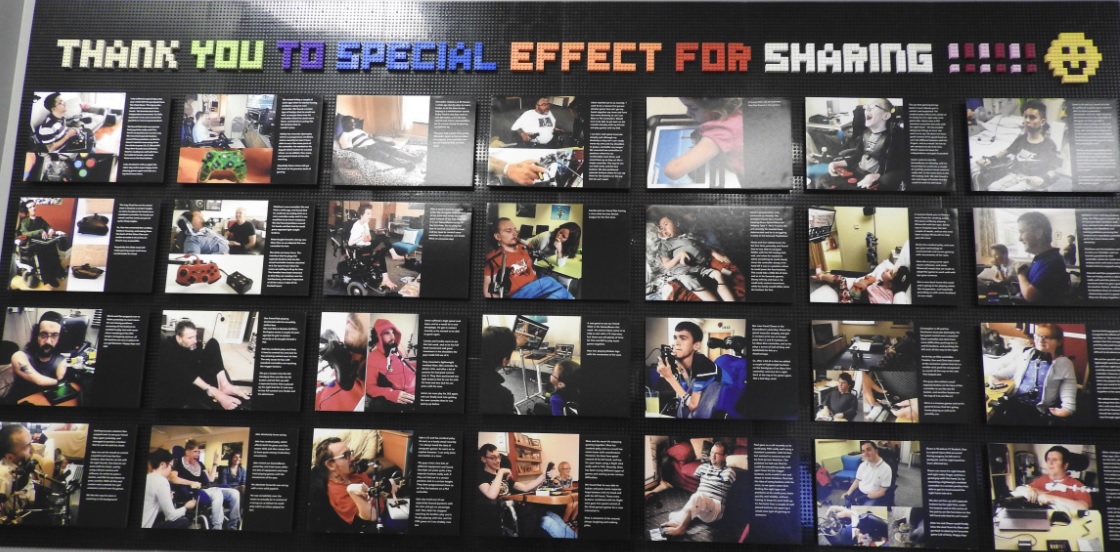

Above: Mark Barlet started AbleGamers to make games more accessible — without driving up costs.

Barlet: To that point, difficulty to me is the joy of progressing through your game. If I’m not enjoying moving forward in your game, then it’s too difficult.

Figueroa: I tend to define difficulty as that friction, but that friction looks different to me even throughout my day. This idea of sliders and that continuum where it’s not linear, but it’s a whole bunch of different options that you can scale and change at any time. As I play a game myself, I change my difficulty needs throughout the game.

McDonald: It might not just be physical, either. Our organization deals more in the mental-health space. There’s a really important game that came out a few a years ago called That Dragon, Cancer made by a father whose child had died of cancer. That game was too emotionally difficult for me. All I had to do was hear about the premise and say, “No.”

Barlet: I was on a judging panel for Games for Change, and they gave me five games to play. One of them was about coming out, which was really interesting. One was about surviving the Holocaust. One was a mental-health game. Afterward, they critiqued the experience, and I said, “If you look at what you gave me, you laid it on real heavy.” And they didn’t even think about this. “You need to give me maybe two games this heavy, not five.”

Figueroa: A Mortician’s Tale — my grandmother passed away, and then, Mortician’s Tale was actually the way I realized I hadn’t dealt with that. I had to stop playing and remove myself, but then continue to use the game to deal with that. It was a beautiful way to deal with it. My first initial response was just….

McDonald: We shouldn’t say that those games don’t have a place or shouldn’t be built. There are just certain considerations that go along with that. Do you want to think about trigger warnings? Do you want to think about changing the perspective of the player in relation to what’s going on? One of the things we see with empathy games is people will try to make a game that traumatizes their player in the name of understanding and awareness, and that might not be the best way to go about it. There are considerations around that.

Figueroa: This is a whole aspect of difficulty that, as an industry, I don’t think we fully understood. Psychology is so important in games. We use psychology in game development knowingly all the time. Difficulty is still one of those things that hasn’t actually clicked, myself included, amongst many people.

Johnson: I would caution us to be very precise with our language, too. In the gaming industry, we like these big buckets of terms like “cheating” and “toxicity” and “difficulty.” There’s a lot of nuance in there. One thing we need to do as an industry when we think about how we classify games is have a very precise way of saying, “This is what this game is. This is what you can expect.” Whether it’s a trigger warning or saying, “Hey, if you don’t have the fingers of a twitchy 17-year-old you may not like this.” It’s metadata.

Figueroa: Barriers in the game versus your unique abilities as a player is another way to define difficulty. How do you go about designing something like that? It needs to be designed from a core mechanic up, especially if you’re looking for options upon options, which really is awesome. How do you go about designing something like that?

Cannon: I think a lot of it is — you start with your core audience. You need to figure out who you’re making this game for, what their literacy level in games is. For Oxenfree, we set out to make a game for people who didn’t necessarily play a lot of games, who didn’t know that generally you press A to confirm things and B to back out of things. That’s something that, from playing games for years, you just get accustomed to.

Our games are unique in that we don’t have much — we’re not trying to make a difficult game, but there is that emotional difficulty. Your main character’s brother has recently passed away, and that’s something that could be difficult to deal with. As you play the game, the choices you have, the dialogue choices, become more and more serious, more weighty. I can see how that’s a kind of difficulty.

Above: Oxenfree is designed to be accessible.

Figueroa: Oxenfree has a unique UI system as well. When you started designing that interface, did you have any reference? Is it something that just naturally came out as the game was developed?

Cannon: The reference was other story-based games like Mass Effect or Walking Dead or any narrative game, where you have dialogue options. We wanted to make that the focus of the game, so we mapped all that to face buttons. That way, you have these three options on the screen that match up to the face buttons. The way that works is very intuitive. We didn’t have to teach the player too much. We just have to say, the first time a choice comes up, “Use these three buttons,” and it makes sense.

Johnson: I always encourage people to make sure that you’re not coming in with too many preconceptions from your own experiences.

Figueroa: Literacy. I love that word.

Johnson: Exactly. Just go out there in the world and talk to other people. Don’t always start from a place where you’re influenced by your own biases.

McDonald: Test, from very early stages, even concept stages, with two very important groups. One is the group of people who you want to include, and the other is subject matter experts. I worked at Schell Games for a while with Jesse Schell, where I was the narrative designer on a project called Play Forward, which was [an] HIV prevention game targeted at 11- to 14-year-old African-American students. Now, I’m about as far as you can get from an 11- to 14-year-old African-American kid, so I realized very quickly that this had to be handled very carefully. We didn’t want to be condescending or patronizing or offensive. I felt a real weight of responsibility to do that the right way.

What I did, I wrote down my story ideas and went to an after-school program where these kids hung out. I would read the story, and they’d act it out in front of me. A lot of the dialogue in that game uses the exact phrasing that these kids were using because we knew it would be relatable. It’s for these kids, so let’s include them. What I found is that when you reach out to include people, they’re so happy that you asked. They’re happy to help you because you care, and you’re trying to do the right thing. What isn’t cool about helping to design a video game?

Figueroa: It’s a barrier because if I don’t feel represented. I don’t feel that I can access that world, which is part of inclusion. In this case, we could also consider that part of difficulty because it’s a friction between me and the game if that representation isn’t there. When it comes to AbleGamers, how easy is it to reach out to the audience? You’re in a middle ground, working directly with people with disabilities as well as game developers. What is that like when it comes to reaching out around the design of difficulty?

Above: Bryce Cannon is lead engineer at Night School Studio.

Barlet: It was really hard for a long time, but I will say that in the last year to 18 months, a lot of the major studios — PlayStation, I think has done this. Through Naughty Dog and some of their work, they’ve put some accessibility guidelines out to all their first-party studios. Microsoft has done that as well for all their first-party studios. The work that AbleGamers has been doing for years — which is to show that people with disabilities are a market, that we have money we want to spend — has finally resonated.

I’m now no longer pointing out accessibility features in games. I’m kind of now pointing places where they’re missing, where I would expect them. Accessibility, especially in the last year and a half or so, has really become the norm. One of the games that came out last year, Battlefield 1, had a color-blind mode that was implemented incorrectly because they didn’t reach out to a color-blind community. They just went and read a paper online. As soon as the game came out, of course, Twitter exploded. But then, they immediately brought in people and said, “We clearly messed up. What do we do to fix it?” One of the first big patches that came out for Battlefield 1 fixed the color-blind mode.

It’s just good design. In my talk, I was talking about how EA used to always win our Game Accessibility of the Year award because they had a good design model and a budget that allowed them to create good design. Battlefield 1 has cognitive accessibility features built into it that no one ever knows about. You might not notice, but you’re always the blue object, and you’re always trying to get to a circle. No matter what team you’re on, you’re always blue, the enemy is always a diamond. This deals with color-blindness, but it also deals with cognitive issues because you don’t have to remember what side you’re on. Red is bad. Diamonds are bad. I want it to be a blue circle. That’s a cognitive accessibility feature.

Johnson: One of the greatest things I’ve seen over the past few years — the advocacy that AbleGamers has done has permeated the industry. I get to be in a place where, when I talk with our first-party developers, it’s not 101. We get to jump in a bit further ahead. They get that they have to deal with things like color-blindness, controller remapping, better subtitles. We can have a conversation about how we go beyond that. We can talk about innovative mechanics and really including a broader audience.

Barlet: To your point, I’m doing a talk at GDC this year on blind gaming, which is an area that we used to avoid because it was so hard. Now that we’ve gotten past the 101 level, where we can expect these basic things to get done, now we can start having more in-depth conversations.

Figueroa: This concept of literacy pairs so well with reaching out to communities and bringing them in to design on that ground level. When you’re designing for a specific audience, so many times our own biases bleed into that. When it comes to designing for specific audiences but across different devices, did you guys do anything different with iPad or mobile versions of your games?

Cannon: When it comes to accessibility, no, sadly. That was a very fast port. But a lot of it is just good design. I feel like you’ll get 80 to 90 percent of the way there just by designing the game well — not using tiny text on the screen, not hiding things too deeply in your UI. We tried to playtest the original game as early as possible. Halfway through the development cycle, once we had a prototype where you could move a capsule around, we would have friends and family try it out and see if it all made sense.

I’m hoping that we can do more for our next game. We didn’t do a lot of intentional design for accessibility. A lot of it was just that 80 to 90 percent. We’re a tiny studio, but we tried to design the UI well. Hopefully, we can tackle that last 10 to 20 percent for Afterparty.

Above: A message on the wall at the Inclusive Technologies Lab.

Figueroa: Part of the same inclusion — for example, I love your talk about how there is no average. If I’m designing for an average person, that person doesn’t exist. Nobody fits into a men’s medium. The sleeves are always too long, or the hem is too short.

Johnson: We have lots of things in our world where — you would never go shopping for a car and expect to buy a small, medium, or large. Ergonomics is a well-known field. We just need to apply the learnings from that field to other things.

McDonald: A few years ago, Raph Koster wrote a book called [A Theory of Fun for Game Design], and in there, he talks about flow, how important it is to have your players maintain a state of flow. Within the last 10 years, that concept is now being taught in game programs all over the world. If you go to game-design classes, flow is a thing you learn about. We were talking, at one of our design hives — what if designing for things like empathy wasn’t just designing to make you feel good? Maybe it’s just like Raph Koster’s flow. Maybe it’s just a question of good design. That’s what I’m hearing right now from Bryant. We’re doing this because it’s good design. That’s what the answer might actually be. If you’re designing well, you’re designing for the maximum number of people.

Barlet: I think you’re onto something there. To your point, difficulty is really around the friction of flow.

Figueroa: Something like Dark Souls is a perfect example. There’s not necessarily a great flow to that game. I love that people have that mastery of skill, but if difficulty is an interruption of flow or a friction of flow, how do skill levels…?

Barlet: Flow is individual as anything else. What one person considers flow might be something you consider not flow at all.

Cannon: I think the flow chart is something like difficulty over skill level, right? As your target audience has greater skill, you can increase that difficulty. It’s not always a bad thing. Something like Dark Souls requires that high level of literacy, that high level of base…. I know how to swing a sword in a game, and I generally know that there are certain times that I’m invincible versus vulnerable. Stuff like that.

Figueroa: Even designing errors. There are so many classic games that hung on this concept of literacy, where you knew that your hitbox was just slightly off in a certain way. [Awesome Games Done Quick] just happened, where people are exploiting all these things. That’s really a kind of flow at that level.

McDonald: I need to fangirl over Cuphead for just a moment. I do not like platformers at all because I’m not skilled at them. I have rheumatoid arthritis, so at times, my hands really aren’t doing what I want them to do very well. Cuphead is a notoriously difficult game, but it was my favorite game of last year because they made failure so much fun. While everyone is complaining about how they just died again, I just found so much joy and so much whimsy in failure there. I wonder if making failure fun in some of these more difficult titles might be a consideration.

Johnson: I do think that, since we’re on this topic of flow, it’s important to recognize that state of flow. Is anyone familiar with the Mary Meeker Report? It comes out every year. It’s this bible of what’s happening in the Valley, and this year was the first year that had a huge gaming section. This is the year that the Valley decided they’re coming for games.

There’s a part in the report that specifically talks about auto-tuning difficulty to keep people in flow. If you think about the economics of the Valley and the stuff that comes out of there, it’s about eyeballs. It’s about time spent. Having people die and leave, no matter what the reason, is basically counterproductive to their business goals. They want to keep people playing. It’ll be interesting to see how games evolve in the next few years based on non-game-makers getting into gaming, basically.

Above: Heidi McDonald is senior creative director at iThrive Games.

Figueroa: Coming full circle on this, arcade games knew how to do this, to get you to put that coin back in and hop back in the game. Dying could be frustrating but fun. These monetization and retention strategies are strategies that we had for a long time, but we’ve forgotten them.

McDonald: One thing we’re working on at iThrive right now is the question of whether it’s possible to design an empathy game on purpose. I’m asking that because Oxenfree was something I thought was one of the best empathy games of last year, and I expect to have some very interesting conversations with these folks about whether they set out to do that or it happened by accident. Lucas Pope, who made Papers, Please — I don’t think he sat down and said, “I’m going to make a good empathy game,” but that doesn’t mean he didn’t do it.

What we have to figure out right now is, the people who did make a good game, did they do it on purpose? And if so, what did they use? Is that something we can take and apply to other designs, or can we come up with a design independently of games that have already been made? That would also extend to other types of ability, I think.

Johnson: In Gaming for Everyone we talk about intentionality a lot. We have a saying that if you don’t intentionally include, you’re going to unintentionally exclude, and if you intentionally exclude, you’re going to be kind of a jerk. But that intentionality is really important. There are lots of happy accidents that we can learn from, but it’s important that when those accidents happen, we document them and understand what made them great. The next time, we can do that intentionally.

Barlet: Accidental accessibility — saying, “Oh, this is good, let’s make sure we bring that forward.” Forza is an example. Forza actually won our competition one year, but then, the next iteration was actually more inaccessible than the one from the year prior. The one that had the Top Gear people on it actually took a regression in accessibility before the next one corrected those issues.

Johnson: We do that a lot at Microsoft [laughter]. We go forward and then back. But I totally see how it happens. If you talk to the team — Aaron, one of the physics designers, we talk about accessibility a lot. He talks about how, “Oh, I made this mode for my kids.”

Barlet: Microsoft does a really good job on closed captioning. The use case we’re talking about was called the Sleeping Baby use case. Microsoft did a studio where they found that a lot of the people who played their games were males aged 28 [to] 35 who were sneaking downstairs to play after the baby went to sleep. They assumed that a lot of them would have the volume low or turned off because if you woke up the baby, your wife was going to destroy you. So, they were designing games with this one use case as part of their thinking. Can you consume this game with no sound? And that was also great for the deaf gamer, but they weren’t setting out to make the game accessible to the deaf. They were making it accessible to a 32-year-old guy with a newborn baby and a wife.

Johnson: I don’t know if you’ve seen this on the Xbox One, but do you remember the snap mode? I’ll tell you where that came from. We saw a post on Reddit where some guy was playing Titanfall, and he’d snap the baby monitor on the side of his screen, so he could play and watch the baby at the same time. That’s where a lot of that inspiration comes from.

Above: Forza Motorsport 7 has more than 700 cars.

Figueroa: One of my friends is creating a kid mode in their game, where it’s local co-op, but the kid is more just running around and having fun. But they’re still experiencing the game. Forza has a similar thing where you can turn it on, so you don’t have collisions. You still have to drive, but it turns a hard game into a casual game.

McDonald: It’s interesting to think about what cases of emergent play are going on in games. I have a 13-year-old son. We bought [Assassin’s Creed Origins], but we have never played through the story or otherwise played the game the way it’s intended. The first time we logged in, my son decided it was way more fun to stampede camels through markets and commandeer boats to drive them through flocks of birds. That’s all we’ve ever done.

Barlet: My 45-year-old husband did the same thing [laughter]. “Are you advancing the story?” “Why should I? Watch this!”

McDonald: Finding out the ways of playing a game that are unconventional, that you don’t know about, and how that can inform your designs going forward.

Johnson: One of the ways I try to sell blind gaming within Xbox is driving and playing games. Basically taking the situational impairment of an eyes-free situation, driving, and then figuring out how to apply that to games.

Barlet: I’m stealing that.

Johnson: You totally should. I would seriously love that, if in a few years we had driving games where….

McDonald: We might be already there? My friend Ed Webb, who made Pugmire — he’s written for a lot of different franchises like Futurama, Vampire, stuff like that. He co-invented a company called Earplay. They’re trying to make games to go with the Alexa system, where it’s totally auditory. It’s a story game, a choose-your-own-adventure, but it’s all audio.

Figueroa: Which, again, is a classic game mechanic. These text-based, choice-based games are something we really loved.

Cannon: We could port Oxenfree to that. Of course, we might not have to worry about that because in self-driving cars, you might just be able to play your game. Except for me. I’d just be in terror looking for a steering wheel.

Going back to what you were saying about empathy, it’s an interesting thought because to me, that’s why we tell stories. It goes hand in hand for games with characters and stories, and that’s what we’re trying to do. I’m really excited for the day when — well, we kind of are in a time where games can join books and films as — where difficulty is the emotional journey you take.

Johnson: Do we see an Oscar for games at some point?

Cannon: I talk to friends about this a lot. The hard thing about games is that we don’t have the equivalent of movie stars — or a part of the development team that’s forward facing to the audience. Designers and programmers and artists in video games aren’t forward-facing people.

McDonald: Devs are famous to other devs. If I see David Gaider, who made Dragon Age, I’ll turn into a stuttering girl. But if you say any of those names to people outside of games, they’ll say, “Who?”

Figueroa: We’re getting a little off-topic now, so I’ll say this and then divert us back. There’s a blending of — maybe we can learn something about good design as the movie industry picks up more and more of our tools like Unreal and Unity. That line is blurring quickly, and it turns out that they have way better established work flows than we do. I feel like there’s borrowing that can happen both ways in terms of accessibility and good design.

Above: Senua from Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice is an ordinary character, except for the blue tattoo.

Audience: What do you guys think of a game like Hellblade? To me, it was interesting because it made the topic of mental illness accessible to people who wouldn’t otherwise understand it because of the way it was built into gameplay. But a lot of people who are interested in the subject possibly couldn’t play that game because it required so much core gaming skill.

McDonald: My team and I are looking at that right now as far as whether there’s any education we can do around that game. Are there any studies that can be done around it to show that it helps people? I know that there have been mixed reactions. Some people think it’s too intense.

Cannon: I played Hellblade a few weeks ago and followed some of the controversy around it. To me, it’s very much a game for gamers that builds empathy for people with mental illness. It sounds like a lot of people who are upset that someone who has psychosis wouldn’t be able to play the game because it wasn’t designed for them, which is — perhaps it should be? But I still think the game had a lot of value in just the fact that — a gamer, someone who plays a lot of games, can understand a tiny bit more what people with that kind of mental illness go through.

McDonald: It was smart of them to use the number of subject matter experts they did, definitely.

Audience: I’m making a game where we’re actively trying to teach empathy, so I’m curious about — we talk about things like mental health, disabilities, blindness, dyslexia, depression. In terms of marketing our game, we feel like it can reach a lot of people, but if we trade on the fact that it’s also about mental-health awareness, we’re wondering if that can deter people. We feel like, in trying to teach people about empathy, we want people who don’t necessarily know what depression is like to play the game, so they can learn more about it and maybe know how to talk to someone else in real life.

Johnson: I personally, in the work we do — we don’t really use the term “empathy building” in a lot of ways. There’s a quotation, and I can never remember who said it, but it goes, “True empathy is knowing that you’re not the other person.” This idea of walking in someone else’s shoes is kind of a misconception. We emphasize that we want to bring people in and hear from them.

There’s also a Harvard Business Review studio that shows that when managers try to empathize, they tend to take the feelings that a person has and internalize it around their own opinions. They end up thinking that the solutions they want are also going to help this other person. Empathy is tricky that way. I’m not trying to be discouraging, but I think it’s very good that you’re cautious about this.

Cannon: I would make a great game and then not tell anybody that it’s an empathy game.

Above: AbleGamers wants everyone to be able to play.

Audience: That’s kind of what we’re leaning toward? But we’re wondering if it would make an impact if we actively said that we’re trying to approach a certain community. We absolutely want to make a game for the mental-health community, but we’re also trying to make a game for people who don’t understand mental-health issues.

McDonald: What I would say to that is, market your game the way you intend to market it for the core audience, but also do side campaigns for these more targeted audiences. You’re going to want to go to the mental-health community and say, “Here was our intention with this game. We’d like to be in dialogue with you about how it can be used in these ways.”

There are researchers around the world who are looking for games to build social and emotional learning curriculums. If you can partner with those people — just like Oxenfree, they did not say that it was an empathy game. They just made their game, and I was so happy to meet him because I have a pair of Norwegian researchers who really want to talk to him. They want to do a social and emotional learning curriculum around Oxenfree that they can use to teach those in schools.

Cannon: Yeah, I would do that secondary marketing push. Your primary marketing push is to sell the game like you want to sell the game, and then, after the cat’s out of the bag, go ahead and do the secondary marketing push.

Audience: We’ve talked a lot about accessibility and building features and trying to be more inclusive. Where does cost play into that? Some things we’ve talked about are cost free, but many of them are not, particularly if the tools involved aren’t already available. How do you deal with that question?

Barlet: The AbleGamers philosophy is to make the game as accessible as you can make it while maintaining your vision and budget. If you think about accessibility early, it’s actually pretty cheap. If you try to bolt it on two weeks before release, it’s really expensive. But I’m not a believer in universal accessibility. I’m a gamer. I want your vision to be realized. If your vision doesn’t include me, I’ll be disappointed, but I’m not going to fault you if you just can’t do it.

As far as I’m concerned, I want your game to be as accessible as it can be, but no matter where I fall on whatever amazing disability spectrum, there’s content I can consume. If you’re pushing a genre and a story, I want your game to exist because it [forwards] the medium I love. If other games are based on what you’ve created that I can play, I’ll reap the rewards of what you’ve created.

McDonald: Some of it has to do with just building a good business case. The talk he gave just before this one laid out a really incredible business case for accessibility. You’re leaving money on the table if you don’t do this. I talked at GDC in 2016 about the business case for queer inclusion in games. That’s something we’re working on at iThrive: How do we build a business case for considering things like empathy and kindness in games? There’s going to be an audience for that … too. It’s just a matter of finding where the money is.

Cannon: I’ll second your point and say, definitely, start early. As a programmer, it helps when you know if you need to have UI elements change color, say, based on color-blindness settings. If you know that early on, it’s much easier to make that happen.

Barlet: Or even better, if you use symbols instead of color, or if you’re doing what’s called second channeling, where you have two ways of showing things, you don’t even have to worry about a color-blind mode at all. You’ve factored that completely out of the equation. Don’t match the red things, match the square things.

Figueroa: I’d also encourage you to push back on your tooling. Voice this to your tooling. If it’s something you’re doing in-house, make the business case to that team. If you’re using an engine that you’re paying for, like Unity or Unreal, voice these needs to them. They only do, mostly, what the audience needs, and the larger a voice you have bringing up these issues, the faster those toolings will become available to you.

Also, if you’re able and you do the tooling in house, now you have a business option to sell that tooling. You sell the game, and then, you can keep that as your market advantage, but you can also turn around and sell that tool.

Johnson: We try to encourage people to target a permanent disability or limitation and then think about the temporary and situational appearances of that limitation. If I design a game to be used by someone who has one arm, then it’s also usable by someone who’s broken an arm or who’s holding a baby. That’s actually the canonical example we use, holding a baby. When [Nintendo’s Shigeru] Miyamoto at the Apple conference said, “Look, you can play [Super Mario Run] while you’re eating a hamburger,” that’s my new one.

Audience: I’ve noticed, as I get older and have children, I appreciate more difficulty settings in games because sometimes, I just want to enjoy the story in a game. I don’t have time to die multiple times. My time’s run out. I have to go to bed and go to work again. When I was very young, you couldn’t make a game too hard for me, and now, if there’s an easy option, I’ll always jump toward that, at least the first time. Maybe this will be a trend going forward as gamers age?

Above: Deus Ex: Mankind Divided examines the augmented future.

Barlet: I talked with the lead developer of Deus Ex when it first came out. He said that a third of his team was storytellers, and the bulk of their expense was voice-over. When you first load the game, it gives you a menu that says, “Tell me a story” or “Give me a challenge, I want the hardest thing in the world.” He said the reason why they did that was, it would have been a tragedy if they spent all this time and money on storytelling and voicing that story and the first jump puzzle made you throw the controller away. Now, you hate the franchise, and you didn’t get to consume this story that the creator’s so proud of. When you go into the easy mode, it’s literally just, boom, boom, you’ve made it. It was a new IP at the time, so he wanted you to be able to get into it.

McDonald: Witcher does that. Dragon Age does that. It’s becoming very common. What I would say is, it’s interesting to take that gamer motivation profile, look at it over the course of several years, and see if your profile changes because it sounds like that’s happening. That might be an interesting study for someone. I’ve always been the adventure gamer, the story gamer. That’s never changed at all since I was 10. There’s a scholar in Germany named Hannah Marston who’s doing some work around this, the way player motivations change as people age.

Figueroa: It would be incredibly boring if our motivations never changed. As a human being, I would hope against hope that we all grow and learn and change as individuals enough….

McDonald: I don’t know. I’m cool just being the story girl [laughter]. I would be completely OK playing story games my whole life because it’s the stories that are different.

Disclosure: Casual Connect paid my way to Anaheim. Our coverage remains objective.