In 2018, mobile gaming accounted for over 74 percent of App Store revenue. With this gold rush comes a slew of new games, to the tune of over 500 per day. This can make it tough to stand out. Two of the biggest methods? Using famous intellectual property, and using augmented reality.

Licensed to make a killing

In an effort to stand out from the crowd, game developers must find ways to draw players. And with so much tied to adoption, revenue and retention, more companies depend on hefty IPs to do the work for them. Jurassic World, Harry Potter, and Pokémon are just a handful of examples. Studios without access to big third party IPs depend even more on sequels, both of which push originality to the side.

That’s not so say everything needs to be revolutionary. Pokémon Go is a great example of something fresh and original utilizing a great IP. Location-based games existed prior to Pokémon Go, but the idea of going out into the real world to “catch ’em all” is the realization of every Pokémon fan’s dream. And the market data expresses that this was a perfect fit. To date, Pokémon Go remains one of the highest-grossing games on mobile.

But here is where things go wrong. Niantic, the makers of Pokémon Go, released another monster IP title last month: Harry Potter: Wizards Unite. Within 18 days of launch, Wizards Unite slipped below Pokémon Go in terms of growth statistics, and it is already below the top 1,000 mark of most-downloaded apps (Pokémon Go remains steady in the top 100).

What happened? How is Pokémon Go doing so well while Wizards Unite (and other seemingly strong IP-based titles) has taken a portkey to the bottom of the charts? What can both those looking to leverage monster IPs and those looking to establish new ones learn from past misfires?

How the mobile games industry works

Free-to-play mobile game development is a delicate art these days. Generally, game studios will start with a “white-paper” concept and hire a focus group firm to gauge on this idea. Others may skip the white paper phase and build a prototype to test with a focus group. Either way, the idea is entirely formed on the studio’s side.

From there, if there are no major red flags, the studio will progress to building out a full Version 1 to release in beta markets like New Zealand or Australia. It is worthwhile to note that the time and investment it takes to get to Version 1 could be over a year in time and millions of dollars worth of effort.

After the beta release, if the retention and monetization metrics don’t live up to expectations, the game may be killed. If the metrics are enough to appease decision makers, the game may get some updates and improvements, and move on to a global release. Some companies, like Supercell and their relatively new game Brawl Stars, have had their games in this beta stage for over a year.

There is one common thing entirely missing from all the standard design and launch procedures of games these days, and that is the immediate feedback loop from the fans of the IP and gamers very early in the process. The lack of fan input can be most easily identified in this hit and miss example with Niantic in regards to Pokemon Go and Harry Potter: Wizard’s Unite.

So how can we change?

Above: Top growth (Pokémon GO vs. Harry Potter Wizards Unite)

Fans know what what they want

Catching Pokémon while walking around — well, that is Pokémon, isn’t it? Pokémon Go captures the core experience of that universe. Harry Potter is known for many things — Hogwarts, spells, Death Eaters, etc. — but very few of these happen while walking around. A simple conversation with any potential player who loves Harry Potter could have predicted this inconsistency — and those are exactly the conversations we should be having.

Harry Potter: Wizards Unite isn’t the only game to struggle to find an audience for not matching its flagship IP’s fantasy. One doesn’t even have to look further than Pokémon itself to find another example. Match-3 game Pokémon Shuffle has fallen off the radar of the general public, which could be attributed to its lack of “traditional” Pokémon gameplay. Other games like Magic: The Gathering — Puzzle Quest don’t match the gameplay of their iconic IPs.

Again, fans know what they want, and they will abandon — or simply not download — games that don’t give it to them.

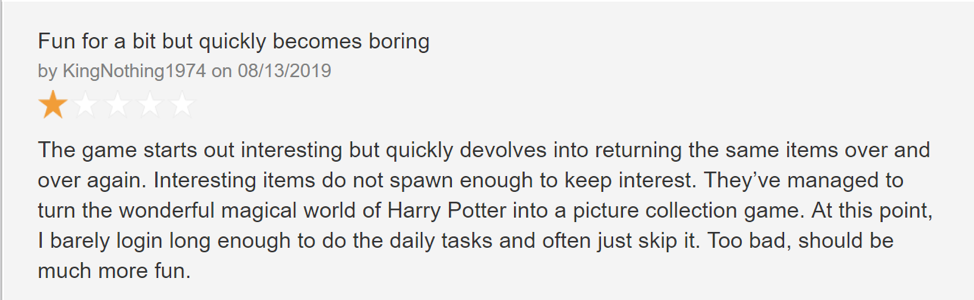

Above: A user review of Wizards Unite

As an industry, mobile game developers tend to rely on early “instincts” based on other successful games and leave most of our last-minute edits to our games during “beta testing” right before release. We don’t do one key thing: talk to our potential players just as development begins ramping up.

This isn’t limited to game studios; look at the new Sonic the Hedgehog movie‘s major embarrassing delay due to poor character design. Movies easily spend hundreds of millions on cast, locations, and crews only to get a dose of reality when fans trash a trailer (or in a game’s case, initial release).

Game studios should talk to their customers sooner in the process of game design, not during early beta when it is way too late to turn around. Players, as the end customers, are pretty quick to know what they’re looking for in a game.

Overcoming the risk involved with developing a game, both from a financial perspective and in terms of reception, can be mitigated by listening to and implementing player feedback. In an ideal scenario, developers begin marketing the concept of a game early on, allowing the community to be a part of their first test group. These initial testers in return bring fresh thoughts and ideas to the table.

While none of these concepts are guaranteed to make it into the game’s final design, open communication with the community affords the designers a preproduction glance at what gamers want and how they react to different elements. The studio can then make modifications early in the development cycle, growing new features organically and accounting for things that seemed like a good idea at the time, but turn out not to be.

The future is feedback

This is an approach that, when applied, is especially useful in the development of augmented reality and location-based games. To date, the location-based game has been a genre of its own, mostly digitized scavenger hunts. For the genre to survive, it needs to seamlessly integrate other mechanics with the location-based features. This is clearly new ground for any game studio; undoubtedly someone can find the lucky formula that players want. However, when trying to adopt something radically different, checking in with the end user first not only seems logical, but also integral.

Players and fans know what works well within the scavenger hunt nature of location-based games, and also what new experiences could easily fit within the genre and provide dynamic gameplay opportunities. Armed with that knowledge, developers can move more rapidly and on firmer footing to create new ways to expand the genre that depends less on getting lucky and finding the right combination through blind trial and error.

While I can’t say with 100 percent certainly no game developers are talking or listening to their end users upfront, before development, I do know the reason major players in the gaming industry have invested in my company. They’ve likely never encountered a game studio that functions by designing games from a marketing-first perspective. Which is to say, involving players in the actual development and building of a game from day one and implementing feedback to create something the community truly wants.

No one can be certain this approach to game design will solve either the uncertainty or the hit-driven nature of the game industry today. It’s a long road from concept to product no matter how you get there, but should this strategy prove successful, it may pave the way for incumbent game studios to learn something from the new kids on the block as well as the audiences they are targeting.

Sami Khan is the co-founder and CEO of Cerberus Interactive.