testsetset

What is the most far-out, insane thing a smartphone could do?

In the final days of 2015, Google’s secretive Advanced Technology and Projects group searched for ways to prove that Project Ara — the never-released modular phone, the anti-iPhone — could do anything, and be anything, for anyone.

The group had already developed unheard-of ways of customizing Ara — from the processor to the screen to the camera — but after three years and three leadership shuffles, high-profile delays and lingering roadblocks forced the team to pivot.

The Ara team had little choice but to start over, and they had to move — fast.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

They set off to build a “shell” from scratch — a full-blown smartphone with slots at the back for radical new hardware that did things smartphones never could. Fueled by an army of contractors, the team created a working prototype in five months.

Google imagined rectangular modules that could tell you the weather with an e-ink display, prop up your phone with a kickstand, record songs with a high-end mic, call a car at the push of a button, and dispense breath mints in a pinch. But Google wanted developers to think bigger, weirder, way further ahead.

As Google neared completion of what would become a last-ditch effort at the shell for an Ara prototype, the company commissioned a team of Brooklyn engineers, designers, and artists to dream up the craziest idea imaginable and squish it down to fit inside a phone.

If you could build an entire phone out of blocks, like a high-tech Lego set, what would you create?

The water bear aquarium

As design briefs go, Google’s wasn’t very precise.

“So they came to us in December of 2015 — and the brief was literally: ‘Here’s Ara. Here’s what it’s going to be. Think of the weirdest possible module for this thing.’ That’s as much direction as we got,” said David Nuñez, Midnight Commercial‘s managing partner.

“They wanted us to make the module that no one else would — they already had the speakers, they already had the cameras and stuff,” said Midnight Commercial founder and creative director Jamie Zigelbaum. The studio had already made a name for itself with quirky art-tech projects like the Barista Bot, a robot that can 3D-print your face in foam on a latte, and the massive Rube Goldberg machine that starred in an OK GO music video.

While Google’s ATAP studio pushed forward to conclude Ara’s multi-year delays with a commercial release — which was at one point slated for Spring 2017, complete with a physical retail store in Los Angeles to showcase the modules — four ideas flowed out of Midnight Commercial’s Downtown Brooklyn headquarters.

One pitch outlined a module that transmits touch, like a high-tech version of the heartbeat feature in the Apple Watch. Another proposed that Google launch a satellite into space: a “super high-end luxury module that would cost thousands of dollars — many, many tens of thousands of dollars. All it would do is give you a connection to this exclusive club of people who own this module that communicates to the satellite.” It was “a very weird concept,” said Nuñez. “They didn’t like that idea.”

And there was an idea for an ink-spraying graffiti printer. “You would take a picture of something — a drawing or a sketch, and then you would turn on your printer app, and then wipe your phone across a surface and it would inkjet spray onto the surface that you were printing.”

And then there was Google’s favorite: an aquarium, a teeny tiny one for your phone, filled with plump little micro-organisms called tardigrades, like a high-tech, living, eating, breathing Tamagotchi.

Midnight Commercial had expected to launch the aquarium module this spring, but Google’s wild hardware dreams shattered last summer, sealing the fate of a project hamstrung by time, money, and worst of all, reality.

Above: Tardigrade footage courtesy of Midnight Commercial

Midnight Commercial engineers swear the tardigrade idea would have worked, with one caveat: it’s your responsibility to keep the creatures alive. The studio could make no guarantees for how long your micro-pets would survive.

Tardigrades had risen in popularity in 2014, at least relative to most algae-chomping microorganisms. Nicknamed “water bears,” the creatures wiggled out of science labs and onto TV by way of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s “Cosmos,” which spoke of the creatures’ mythical indestructibility. The bizarre organisms, with their fat, wiggly legs and razor-mouthed snouts, can theoretically survive the most impossible conditions: the vacuum of space, radiation, freezing temperatures, and extreme heat. That’s the story, at least.

“So the idea is we create a small sealed biome with microorganisms, tardigrades, maybe some others, algae, and a solution that is balanced so that it can live for a long, indefinite period of time. That little sealed biome would sit on top of a digital microscope and that would be sealed in the module, and then through the phone itself you could look in and see the micro-organisms in real time that live in your phone. I think we were doing something like 30x optical zoom,” said Zigelbaum.

It was a party trick. An expensive one. And a perfect fit for the off-beat engineer- and designer-types already swooning over Google’s modular phone. It was an art piece you could carry around in your pocket: the perfect mad science concoction for an era of weird hardware at Google.

Above: An early mockup of the Tardigrade module, by Midnight Commercial

“It gets to something really big and emerging in culture, which is how the phone is a part of our body — it stays in bed with us, it’s in our pockets, it’s this intimate thing that extends the body,” said Zigelbaum. “By putting life forms — pets — into your phone, it’s a way to access some of the thinking around the barrier between organisms, technology, and what the boundary of the human body really is. And that was really exciting for us.”

That idea, to the few people who learned about the project under Google’s strict non-disclosure agreement, was tailor-made for Ara. Google gave Midnight Commercial’s concept the green light. But first the studio had to prove it was even possible. One thing was certain: In order for the idea to take off, it had to be real. No faking.

The prototypes

Now, a year later, inside Midnight Commercial’s new office in Brooklyn’s maze-like Navy Yard, four engineers — Noah Feehan, Matt Borgatti, Sam Posner, and Jesse T. Gonzalez — circled up to walk me through the dusted-off plastic and silicon prototypes sitting on lab desks, now full of dried-up algae and dead tardigrades.

The engineers attempted a postmortem of the project. “There was no roadmap for doing this. We needed to create a bunch of experimental equipment so we could start evaluating some of our assumptions and we started gathering experts … So we’d read a paper, talk about stuff, and we would essentially have our homework checked by a person who did optical engineering every hour of every day,” said Borgatti.

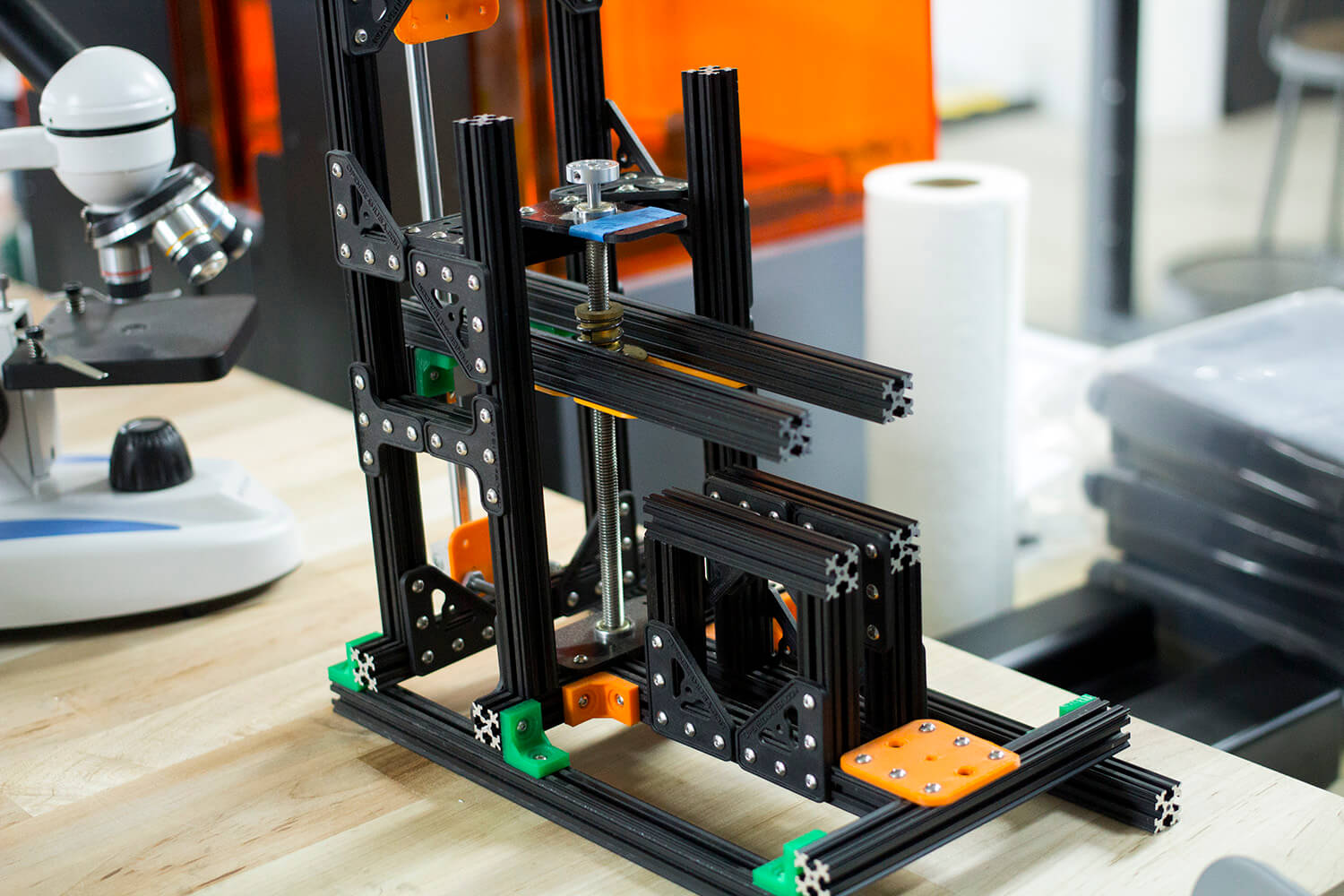

The first prototype, a very rudimentary one, was created in one night with off-the-shelf OpenBeam prototyping tools and a $35 Raspberry Pie minicomputer.

Above: The first prototype

“The first, first sample was Saran-wrapped with a water droplet from our now-perished algae sample, hooked up to a screen. We could see tardigrades moving around …This allowed us to very precisely understand the distance from the imager at which the image looked best,” said Feehan.

“The key was, how do you squish everything down to pocket-sized, because the phone already takes up some space? We only had a couple of millimeters to play with the optics,” explained Borgatti. They had 5 millimeters to work with, to be exact, smaller than the diameter of a number two pencil.

Feehan’s first prototype taught the team how to successfully capture images of the tardigrades. “We got to this point where we could start experimenting with what different biological samples look like if you can just snap them in and out. Different lighting. Does it need to be columnated? What happens when it’s only one color?” said Borgatti.

Above: One of the second-generation prototypes.

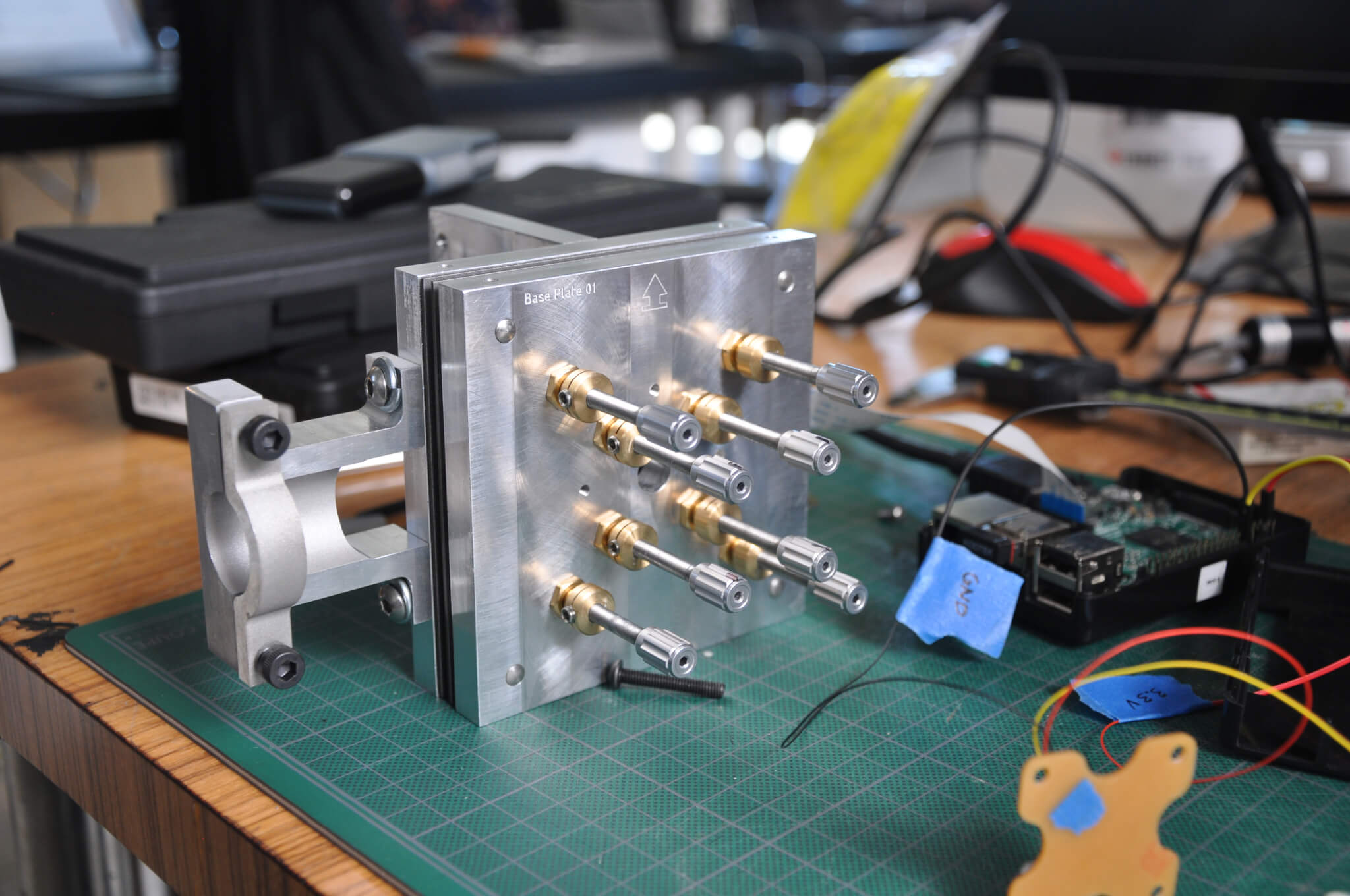

“Magnification is easy when two lenses are far away, like a telescope — hard when two lenses are close together … We discovered we could use micro lens arrays, lots of small round lenses that are all together that produce a little bit of distortion each, but you can cancel the distortion out because they each overlap.”

With the micro lens arrays, Posner developed an image reconstruction technique to produce clear images in the module’s companion Android app on the fly, allowing for a margin of error during assembly, said Feehan. “We got that working on the actual handset.” Unfortunately, that prototype handset was collected by Google last August, like all the others, when the project was abruptly cancelled.

Above: The “POE” prototype (Precision Optical Evaluation Assembly), which enabled the team to test the lens arrays

Midnight Commercial’s second series of prototypes took on more than 30 different variations through April. “The most fun part was going from a meeting about micro lens array optics to a meeting about what hats should the tardigrades wear, if we’re going to let that happen,” said Posner.

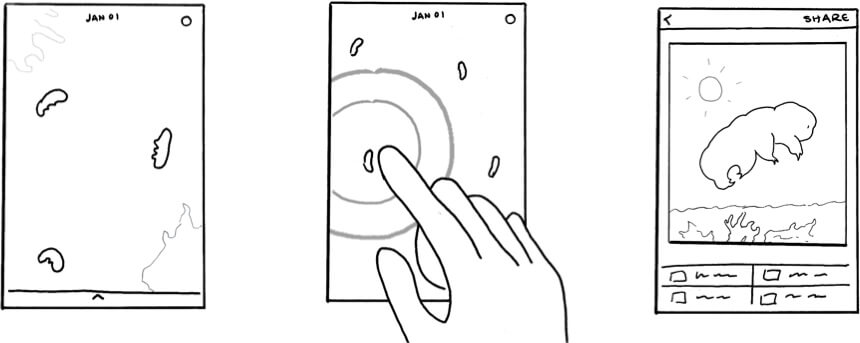

The team, together with former Midnight Commercial designer Bailey Meadows, explored ideas spanning tardigrade chatbots, group chat, and tardigrade outfits, but ultimately killed the add-ons to focus on the core theme. “It needed to feel like a world that you were just peeking into,” said Nuñez.

Above: An early illustration of the Tardigrade app, by Midnight Commercial

The module’s companion app would let you watch your tardigrades in real time as they swim around, wiggle their clawed paws, eat algae, and reproduce. But a consultant on the project, William Shindel of biotech nonprofit Genspace, discovered a very different behavior when he returned to the lab after a long weekend: A strain of tardigrades he was testing, a carnivorous strain, had turned to cannibalism inside a prototype biome. “And to be honest, that’s an excellent app experience,” said Feehan.

But that moment marked a much bigger problem for the aquarium. Knee-deep into development, the team hit a wall: They couldn’t keep the tardigrades alive. Cannibalism was the least of it.

Despite the myths, common lab-bred tardigrades — the kind you can easily find online — are sensitive to heat — the kind of heat that radiates off the little digital cameras Midnight Commercial embedded inside its prototypes. The heat was enough to kill off the micro-animals. About two hours of the camera being left on seemed to do it.

Now, imagine tardigrade pet owners on a hot summer’s day, sprinting for the air-conditioned indoors, or even the nearest refrigerator, racing against time to keep their critters alive.

It turns out the myths about tardigrades — how they’re indestructible — are true, under the right circumstances. “They go into cryptobiosis. They shed up to 90 percent of their body water, turn into a little grain of rice, and that is the thing that survives in space, and that’s what survives in ice cores for 300 years, and you add water and they revive. Cryptobiosis requires very narrow environmental ranges in order to begin,” said Feehan.

But a sudden change in temperature? Lab-bred tardigrades are no match for that.

“It’s sort of like bears hibernating, where they need the environmental signals to tell them to do the thing. And they need time to do the thing. We kept being like, ‘Why are all these guys dead?’ And it was like, ‘Oh, it was a 70-degree day. That’s why they’re all dead,’” said Borgatti.

Undaunted, the team even sent one consultant to a hot springs in search of hardier, heat-loving tardigrades.

“The first time that we discovered that the camera being on was an obstacle for these guys staying alive was a little bit of a frightening moment. It got to such a temperature where these guys were dying off, and if you don’t think about it too hard, that’s almost like, ‘Oh my gosh, how are you going to take pictures of these guys if they can’t survive for a long period of time when the camera’s on?’ That’s kind of a mini-crisis that sort of requires a lot of rethinking,” said Gonzalez.

The team “collected data on shaking, rapid heat changes, suffocation, and population control,” said project manager Jennifer Bernstein, Midnight Commercial’s main contact with Google. But unlike a virtual Tamagotchi pet, tardigrades are living creatures. And if they die before reproducing, all they leave behind is algae.

Midnight Commercial resolved to fix the problem with software. The engineers designed the experience around nudges that let you “play” with your tardigrades without killing them with love. “If you’ve been looking at [them] too much, we’d have a control that says, the next time you try to open the app if it hasn’t cooled down enough, it would say ‘They’re resting right now, why don’t you see some videos that we’ve taken before’, or what-not,” said Feehan.

“We had started out with: ‘It’s going to be a tardigrade parade’, and we ended up realizing that the most durable experience was going to be the miracle that is this whole world in this little drop. The algae on its own, watching it bloom or being eaten, is just as interesting.” The team planned for the biome to eventually include rotifers, ostracods, and a spotter’s manual to help module owners identify their micro-pets.

“Getting that mix, it’s like a witch’s brew of algae and tardigrades and other creatures. And the salinity of the water, getting that chemistry right, that was gonna be the hardest thing about the project. And by the time the project got canceled, we probably weren’t very close to solving that, to be honest. But just getting the microscope and the module, we could have probably been ready for manufacturing by the spring of 2017,” said Nuñez.

As the next-generation prototypes progressed, the team began designing the actual module.

Above: The latest Tardigrade module design

“The optical stack, just by nature of what it was, was going to be very odd-looking. We have this hole, inside of a board, that’s got a tiny camera module, that has this little opaque housing for the tardigrades, and micro lens arrays, and they’ve got to be soldered in just so. It was guaranteed to look alien,” said Borgatti.

The miniature biome couldn’t be entirely see-through, like in the earliest mockups, because light “needed to be coming in through the micro lens array in a structured way. But we could show what it was doing by making certain elements of it transparent. It’s almost like a car with a transparent hood; you’re not seeing inside the engine, but you can see it’s working, and you can see that there’s a complex truth inside of there,” said Borgatti.

‘It would have worked’

Midnight Commercial didn’t bet on selling millions of the Tardigrade module. In the end, had it gone into production, the studio would have priced its Tardigrade modules like limited edition art pieces. They would have been for sale inside Google’s online store and on display at its Los Angeles brick and mortar. In all, there were 27 other modules under development by Google and its closest partners.

Before Google cancelled Ara in August 2016, an avalanche of module proposals had poured in from outside developers — over 1,000, a source familiar with the matter told VentureBeat. Of those ideas, “there were at least 100 credible submissions that [Google was] going to pursue,” the source said. Many of the modules that were in development remain a mystery. None, you can likely bet, was anything close to the water bear aquarium.

When Google shut the Tardigrade project down, “we were literally like a week away from connecting the optics stack to the app. It was like all working,” said Posner.

“It was one of the few things that you couldn’t possibly ship a phone with. There was no way that Apple was going to produce a phone that did that,” said Borgatti. “We shot for the moon with this crazy thing, and someone said yes, and from that moment, we were like, ‘We’re on borrowed time. This is crazy.’ And I’m amazed we got so far. We did so much.”

“It would have worked,” insists Posner.

“We were going to make something just totally new, and weird, and amazing, and because Google had faith in us, because the project was so interesting … we were all pretty much emotionally devastated when the project was canceled, because we were so invested and excited by it,” said Zigelbaum.

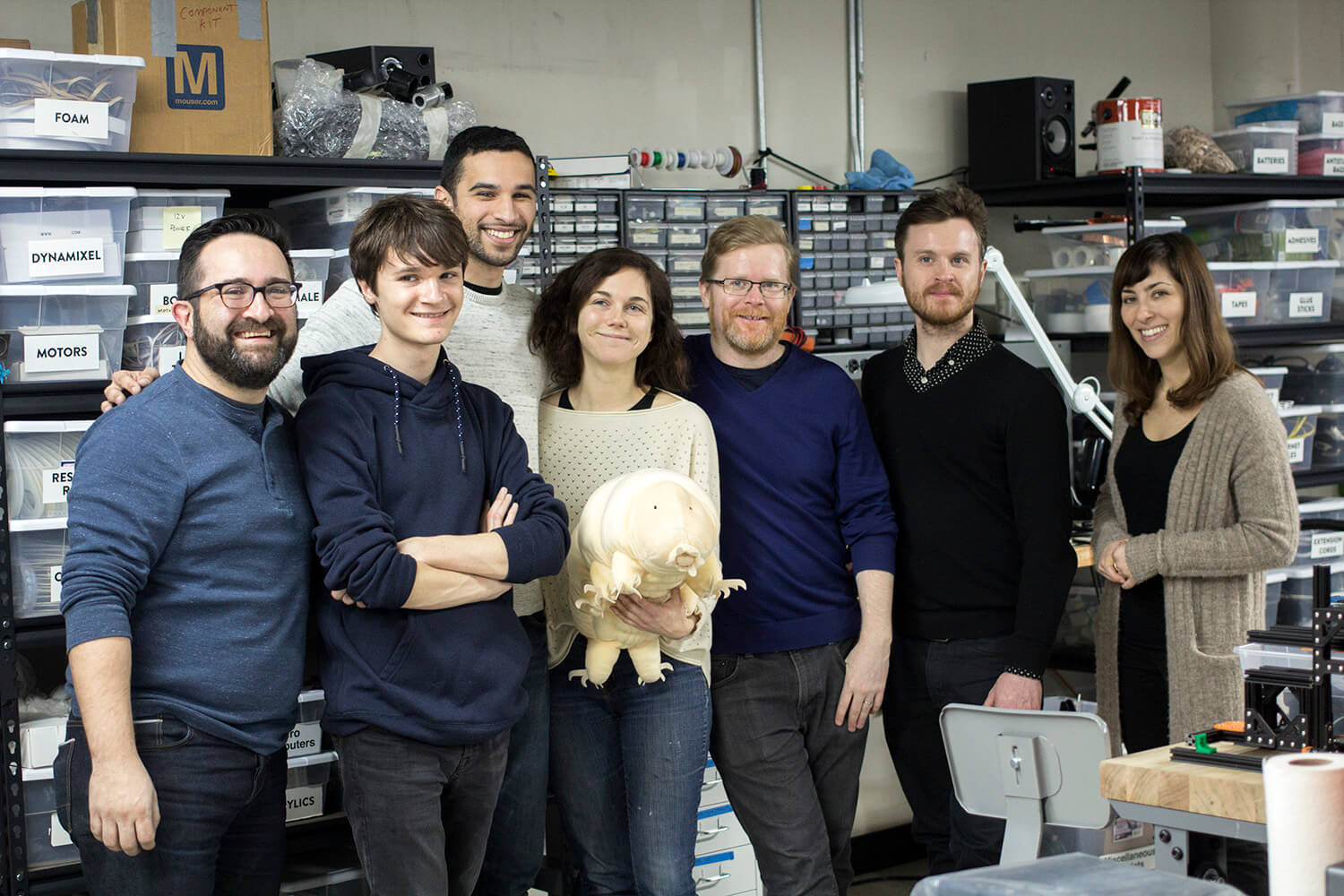

Above: The team, left to right: David Nuñez, Sam Posner, Jesse T. Gonzalez, Bailey Meadows, stuffed animal tardigrade, Noah Feehan, Matt Borgatti, and Jennifer Bernstein

The circumstances that led to the Ara project and the aquarium module were beyond rare. It was not an idea most companies would dare throw money at, and ultimately even Google bailed.

“It was a magic combination of Google being really progressive and reaching out to companies like ours, saying ‘Go for it, do this thing’. The boring stuff like making a lot of money off this thing, it wasn’t about that. It was this art piece,” said Nuñez.

The Tardigrade module’s appeal was wholly unproven, like the Ara phone itself. But Midnight Commercial may someday pursue it without Google, said Zigelbaum, possibly as a standalone device you could keep on your desk. But, he acknowledged, it loses its effect without the phone.

In the months since, Google has moved on. The company, once known for moonshots, settled for something much safer than Ara last fall: its Pixel smartphone. The Pixel is fundamentally a lot like an iPhone, both in design and features, save for the optional cobalt blue finish. It was the safe choice. Demand for the iPhone was proven. An experimental modular phone was the opposite. It was daring, visionary and — a huge risk.

The Tardigrade module was also unproven. Complicated. Weird. Beautiful.

“This was a chance to prompt a really cool conversation that never got to happen,” said Nuñez. Maybe it never will. Not any time soon, at least.

It was the most far-out dream of what a smartphone could do, if only smartphones were modular.

More: Listen to the author talk about this story on 60db.