Understanding cellular technology begins with one key piece of information: Cell phones, personal hotspot pucks, and other cellular devices are all sophisticated two-way radios, such that each new generation (2G, 3G, 4G, 5G) adds additional ways to speed up the radio communications between your device and nearby towers. One way to boost speeds is to send more complex signals on a given radio frequency, another is to add more frequencies — more radio spectrum — so more signals can be sent at once.

Because spectrum has become a major topic in the 5G era, we wanted to demystify it for readers by talking with an expert in the field. We spoke with Qualcomm senior VP of Spectrum Strategy and Technology Policy Dean Brenner, who has been a key advocate for improving cellular spectrum availability across the world.

Here’s a transcript of our interview that has been lightly edited for clarity and flow.

VentureBeat: Wireless engineers understand spectrum, but most end users have no idea what it is or why it matters. Could you provide a quick explanation of the concept for readers?

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

Dean Brenner: Spectrum is the mother’s milk of wireless technology. The phone in your pocket has a radio inside, just like the radio that’s in a car. And that radio operates on different frequencies. Just like in cars, you change the dial from one radio station to another, and then what you’re doing is moving from one frequency to another. The same thing goes on when your phone is communicating with a cell tower or a small cell. Together, they’re using some part of the wireless spectrum, some radio spectrum band in order to communicate.

Every single time you make or receive a call with your phone, you’re using some part of the spectrum. Initially, the first cell phones only used one spectrum. And in the 1G and 2G world, we started using multiple spectrum bands. And as things have gotten more complex — 2G, 3G, 4G — we add more and more different spectrum bands.

As a chip vendor, we invest and do a huge amount of R&D to ensure that our chips work on all the different spectrum bands that are used for now 5G, 4G, 3G, and 2G — not just in the United States, but all over the world.

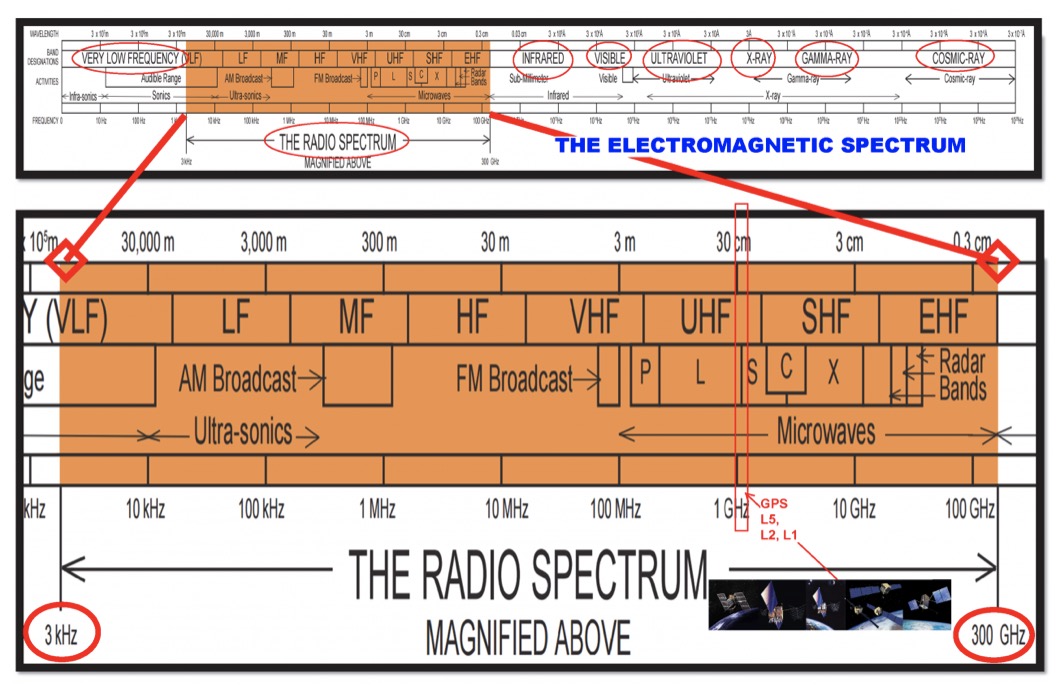

Above: Radio waves range from a low 3 kilohertz (kHz) to a high of 300 gigahertz (GHz), but until 5G, no cellular devices went higher than 5 GHz, and then only for Wi-Fi. Some early 5G phones will be able to use up to 39GHz frequencies.

VentureBeat: 5G phones are adding millimeter wave (24-39GHz) spectrum support. What else is happening in the spectrum world right now?

Brenner: Whenever we launch a new technology, a new G, we start off and we launch it in new spectrum. And so we go to the FCC, we go to the spectrum regulators all over the world, and Qualcomm operators all over the world. And we find some new spectrum band or bands in this case, and we ask the regulators to make them available. When the spectrum is made available, the technology launches in a new spectrum band.

Then we try to migrate the technology into existing spectrum bands, but the way that has typically worked in the past is you have to empty the band of the incumbent technology. For example, we couldn’t launch 4G in the bands that had 3G until there were so many 4G phones and 4G users out there who were using other bands that we could empty the legacy bands and then redeploy it. We call that process re-farming. It’s like re-farming a field: If the field is used for tomatoes, you can’t put corn there until you no longer have any tomato plants. And that’s really what’s gone on in the spectrum world.

But for 5G, we have a game changer. And the game changer is a new technology called dynamic spectrum sharing, sometimes called DSS. It enables the phone and the base station to have 5G in a spectrum band that also has 4G users at a given location — as long as the base station is capable of supporting this feature, and as long as the phone does. You’ll start to see this in phones with a second-generation Qualcomm chip.

Take a 5G phone with a base station in a spectral band that also has 4G users. The phone tells the base station, “Hey, I want to do 5G,” and the base station says, “Okay, let me let me segregate some piece of the spectrum in that location for you. Yeah, I can do that.” And, voilà, all of a sudden we have 5G in a band that’s used today for 4G. Why is that a huge game changer? Well, we’ve now taken the process, that re-farming process that typically could take 10 years, and we’re enabling it overnight.

So that means all of the existing sub-6GHz spectrum bands that have great coverage, you’re going to see in the 2020 time frame — once our second-generation chip is out there in phones, and once the base stations are ready. This is going to be a gigantic game changer. It’s going to lead to much more rapid proliferation of 5G than you’ve seen in the past.

Above: AT&T is now publicly differentiating between sub-6GHz “5G” and millimeter wave “5G+” spectrum.

VentureBeat: Over the past four generations of cellular technology, spectrum wasn’t a consumer-facing issue. A phone was either “4G” or it wasn’t. That’s changed with 5G because there’s a big focus on how low-, midrange, and high-frequency spectrum have different pros and cons for 5G devices. We’re now seeing some carriers use terms like “5G” and “5G+” to publicly distinguish two key types of 5G spectrum to consumers — medium-range, mid-speed “sub-6GHz” spectrum and short-distance but high-speed millimeter wave spectrum. Is this a positive or negative development?

Brenner: I’m neutral on all that. I don’t know what marketing people at all these operators know about how to explain these things to the average person, so I’m going to approach that with a lot of humility.

I agree with your premise — people don’t look under the hood. Everyone wants the best connectivity possible. In the history of the world, no one’s given a phone back and said, you know, the connectivity’s too good, I don’t need anything that works that fast. Everyone wants the best connectivity, and unlocking spectrum is absolutely a vital part of delivering that.

Above: Korea Telecom (KT) announcing its imminent plan to launch a 5G network in South Korea at Mobile World Congress 2019.

VentureBeat: The transition to this new cellular technology has been incredibly smooth, or at least it has seemed like that from the outside. I’ve heard that you’re apparently not a believer in the idea of a “5G race.” But when I think about what seems to have motivated policymakers, the idea of having a race that they need to finish first seems to have been working. What is your thought on the “5G race” — should it be a real thing or not?

Brenner: What I’ve always said about the “race” is it’s a great metaphor. It’s a great 30-second sound bite, it’s a great bumper sticker. It’s something everyone can relate to — we’ve all been in races.

The second thing is, we’re Qualcomm, and we want everyone around the world to have 5G as quickly as possible. The reason I push back on [the race metaphor] is it implies an ordering that if you’re not first, you’re out of luck, you’re somehow inferior, you’ve done something wrong. We’re not trying to have just one winner around the world; we want everyone to sail through the tape as a winner.

So my problem with the race analogy is that I worry about the concept of branding countries or regions as, you know, second, third, fourth, fifth place. That’s my main problem with it. Having said that, we are very happy about how quickly 5G is launching all over the world. And in fact, it is a race. We have countries on four continents that have already crossed through the tape.

But it isn’t just a one-time race, like a 100-yard dash. The deployment of new wireless technology is an ongoing process, and at Qualcomm, the first-generation phones are being launched, we’re already in production with chips for the second generation, and we’re deep into the planning for the third generation. So it isn’t a static one-time event. If it’s a race, it’s more of a perpetual race. It doesn’t have a starting point and an end date.

Above: Qualcomm president Cristiano Amon shows off the company’s first live 5G reference phone design in December 2018.

VentureBeat: Given that we’re taking a look at the international picture here, we have small countries in the Middle East that launched preliminary 5G very early, without actual devices to sell. Meanwhile, we have countries such as Russia, India, and parts of Europe that are sort of slowly moving toward 5G. What’s going on in countries that aren’t ahead of the curve on this? And why?

Brenner: I’m not going to comment on Russia for a variety of reasons. But in prior generations, a big part of what a government affairs spectrum person would have to do would be to convince regulators why it’s important that their country or their region take a leading position in deployment in the launch. For 5G, everyone in the government — certainly everyone in the governments that I’ve had any dealings with, and again, I’m not talking about Russia — I’ve been all over the world since 5G was in formation, and I’ve never had to convince a regulator about why it’s important, or why it would drive economic growth in their part of the world. Everyone gets that, and back to the race metaphor, everyone wants to be at the forefront of 5G from a government point of view.

So there are obvious practical — country to country, region to region — governance issues, all kinds of issues. But I don’t think there’s a lack of will in any government around the world about wanting to get 5G deployed for their citizens quickly.

VentureBeat: So it tends to be more of just a bureaucratic question.

Brenner: Yeah, unique, practical issues.

VentureBeat: What’s going on with millimeter wave at this point? Has the pace of approvals cooled off at all?

Brenner: I think that millimeter wave is firing on all cylinders. The European Commission just came out with the European-wide ruling on the 26GHz millimeter wave band. This is a normal process whenever a new G launches and, as you know, the first 4G phones are nothing like the 4G phones that are in our pockets today. This is absolutely par for the course, and we’re very happy with the way things are going.

Obviously, everyone in the industry, especially the carriers, would like to hit the fast-forward button and drive more devices and deployments as quickly as possible. They’re investing billions of dollars to do that. So as far as I’m concerned, and as far as Qualcomm is concerned, I think we’re very happy with how quickly things have gotten out there, but you know, we never rest on any of that.

Above: Most early 5G smartphones have been designed to operate on either millimeter wave or sub-6GHz 5G networks, not both, depending on where they’re sold.

VentureBeat: Thinking back to prior phone generations, one of the big goals for each generation is a “world phone” — a phone that’s capable of working outside your home country on whatever the dominant new network standard is, pretty much everywhere in the world. How far are we from having such a thing for 5G?

Brenner: I agree with you that’s what everyone wants, and the fact that we were basically able to achieve that — maybe not totally perfectly — for 4G is a phenomenal accomplishment. I can’t give you a date when that’s going to happen with 5G, but I think that’s absolutely a goal that is shared across the wireless industry.

The fact that we have that for 4G, the fact that we don’t have a technology war with 5G — we have the 5G NR standard — and the fact that the spectrum, while not identical, is basically in common ranges, I think all that augurs very well to have that in place quickly. I can’t give you a date; I can’t say it’s going to be March 23, 2021 or something. But that’s not science fiction, that’s not a fantasy. That’s absolutely going to happen. I don’t have any doubt about that.

VentureBeat: Will one phone be able to address all the sub-1GHz, sub-6GHz, and millimeter wave frequencies for 5G? Will most of the phones be capable of tuning across all those frequencies, or is it likely that a phone will address two of them at most and not be able to go up or down to the others? Where do you think that the hardware is going to be over the next couple of years?

Brenner: Great question. Right now, we support both sub-6GHz and millimeter waves in the same Qualcomm 5G chip.

VentureBeat: So users understand, a phone that’s capable of doing sub-6GHz generally is going to be able to reach down into the sub-1GHz bands as well. One pocket-sized device will be capable of containing all the antenna hardware that’s necessary to address everything from 600MHz all the way up to 28 or 39GHz?

Brenner: Oh, yeah. It certainly is possible. We have these modules, these antenna modules that we invented, that are tiny, that have like seven or eight antenna elements. And then each of the first 5G phones that has a Qualcomm implementation has multiple, like three or four of these modules. So yes, the phone is definitely capable of doing sub-1GHz, mid-bands, and millimeter wave. Today, the first 5G phones are capable of doing that. With the second-generation and third-generation [chips], it’s more about adding complexity with carrier aggregation, and complexity on top of complexity. But the core idea that a phone needs to support all the legacy 4G bands and new 5G bands, that’s table stakes.

VentureBeat: One last question — any further clues as to what Qualcomm’s third-generation 5G chip is going to bring to the table?

Brenner: I don’t think we’ve announced the third-generation chip yet, so stay tuned for that. Usually we’re on a cadence, so I think we’ll probably talk about it in October.