In an attempt to limit virus transmission, big parts of the world are progressively locking down. For an undetermined period of time, social distancing will force us to live our lives in a totally different way. Even before governments took drastic action, many companies had asked employees to work from home, shifted working hours to avoid crowded public transport, or implemented split teams (teams A and B alternatively working from home every two weeks).

When the crisis ends, many of our old habits — including the idea that one has to leave home to go to the workplace on a daily basis — will have changed. And the new habits we’re now building could help solve a long-standing problem no one has been able to solve to date: traffic congestion.

Congestion is a serious issue. It costs drivers billions of dollars every year in lost time (about $88 billion in the US alone in 2019, according to one study), contributes massively to greenhouse gas emissions, and has increased by about 15-20% over the last decade in a majority of large urban areas across the globe, according to TomTomIndex data from 2008 to 2018.

Not much has been done so far to fight the issue. Only three approaches have been experimented with. The first is to increase public transit capacity, but that is only efficient when new investments reach tens of billions of dollars, a sum that is out of reach for most cities around the world.

June 5th: The AI Audit in NYC

Join us next week in NYC to engage with top executive leaders, delving into strategies for auditing AI models to ensure fairness, optimal performance, and ethical compliance across diverse organizations. Secure your attendance for this exclusive invite-only event.

The second is the aggressive promotion of green transportation such as bikes or

innovative shared first- and last-mile solutions (such as the Via and LA Metro partnership). Regarding bikes, the most radical cities, such as Amsterdam and Copenhagen, have won that battle. (Between 2006 and 2016, for example, Copenhagen invested $317 million to push cycling and saw bike transport move from about 30% in the early 2000s to 41% in 2016, according to the book Copenhaganize). Others are stuck in the middle with increased congestion due to reduced road space as a consequence of dedicated bike lanes. Meanwhile, bike use as a means of transport to work has increased but remains low in a majority of Western cities.

The third is the introduction of congestion-pricing regulation, which has proven its efficiency but remains controversial.

In the long run, all of these solutions will have beneficial impacts in the fight to remove the number of cars from the roads, but in many cities, they have not yet proven effective. As of now, public authorities have failed due to basic game theory properties: the individual benefits of changing one’s habits have remained much lower than the individual costs. In other words, none of these strategies have delivered high enough benefits to individuals to induce them to take part.

But in the current environment, where many people have been forced to travel less and work remotely, the individual benefits could become clearer.

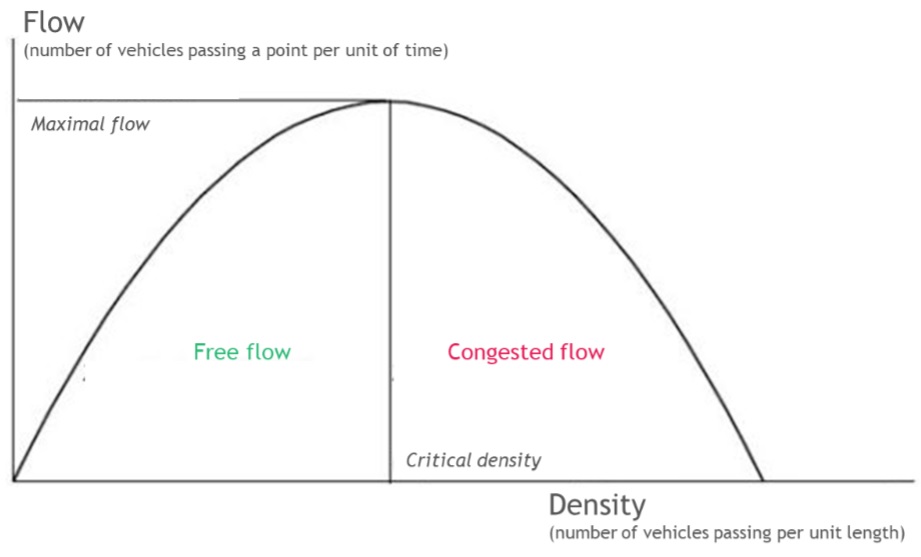

Traffic works like fluid mechanics: The relationship between density and flow is not linear but parabolic. When traffic is congested, a rather small reduction in cars on the road can have a very positive impact on traffic flow. So eliminating a small share of morning and evening commuting flows would have a great impact on the speed of those still traveling.

We can already measure this positive effect on congestion: In the San Francisco Bay Area, across the Dumbarton Bridge linking East Bay commuters to Silicon Valley, the traffic was down 18% during rush hours last Monday compared to a week earlier. A number of the largest tech companies in the area had asked their employees to work from home as much as possible. Other extraordinary events have led to similar positive effects on transportation networks. Last December, Parisians experienced massive public transportation strikes, which also made many workers work from home. On the first day of the strikes (December 5), traffic jams in the Paris region were down by 45% and the few remaining suburban trains had never been as much on time.

However, recent measures taken for the COVID-19 crisis show that a more permanent solution to congestion is possible if private companies and public authorities coordinate to:

- Adapt working hours for specific sectors in order to better distribute cars over the time during rush hours.

- Incentivize and promote working from home. For a large share of jobs, all required tools are available remotely, and working from home hasn’t shown any reduction in productivity.

- Test alternated circulation at scale. This could be done by alternatively banning cars based on the last number of their license plate. Once every 10 days, people would be forced to leave their car at home and fall back on another mode of transportation, helping residents to switch from cars to alternatives on the long run.

It goes without saying that no one wants the current crisis to worsen, dramatically affecting more people, forcing companies to stop their business and paralyzing entire countries. However in every situation, and even in the most difficult one, it is always worth stepping back and analyzing side phenomena that could lead to efficient solutions to be applied in more peaceful times.

Joël Hazan is a managing director and partner of Boston Consulting Group. He advises cities, governments, OEMs, transport agencies and startups on the future of mobility as a member of BCG’s Center for Mobility Innovation and as a BCG Henderson Institute fellow.

Benjamin Fassenot is a consultant at BCG.